Continuing Education Activity

Hepatitis is defined as inflammation of the liver that can result from a variety of causes, such as heavy alcohol use, autoimmune disorders, drugs, or toxins. However, the most frequent cause of hepatitis is due to a viral infection, referred to as "viral hepatitis." Several different strains of viruses can cause hepatitis. In the United States, the most common types of viral hepatitis are hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The other types of viral hepatitis are hepatitis D and E, which are encountered less frequently.

The severity and duration of the hepatitis are variable depending on the pathogen and comorbidities. Based on the etiology of hepatitis, the severity can range from mild, nearly asymptomatic, to severe illness requiring liver transplantation. Hepatitis can be further classified into "acute" and "chronic" based on the duration of the inflammation in the liver. Depending on the type, hepatitis can be self-limited and resolve quickly, while others can become more chronic and last years. Some individuals may rapidly progress to fulminant liver failure, while others may be asymptomatic carriers.

This activity reviews the causes of viral hepatitis, its epidemiology, symptomatology, patient evaluation, treatment, prognosis, and preventive strategies. It also highlights the role and importance of a multidisciplinary healthcare team in caring for patients with viral hepatitis.

Objectives:

Differentiate the etiology, epidemiology, and pathophysiology of the various types of viral hepatitis.

Implement evidence-based treatment and preventive strategies for viral hepatitis.

Identify common complications of viral hepatitis.

Apply effective interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance and improve outcomes for patients with viral hepatitis.

Introduction

Hepatitis is defined as inflammation of the liver that can result from a variety of causes, such as heavy alcohol use, autoimmune disorders, drugs, or toxins. However, the most frequent cause of hepatitis is due to a viral infection, referred to as "viral hepatitis." In the United States, the most common types of viral hepatitis are hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The other types of viral hepatitis are hepatitis D and E, which are less frequently encountered.[1]

Based on the etiology of the hepatitis, the severity can range from mild and self-limiting to severe illness requiring liver transplantation. Hepatitis can be further classified into "acute" and "chronic" based on the duration of the inflammation in the liver. Inflammation lasting less than 6 months is defined as "acute," and inflammation lasting greater than 6 months is defined as "chronic." Although acute hepatitis is usually self-limiting, it may also cause fulminant liver failure, depending on the etiology. In contrast, chronic hepatitis may result in the development of liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and features of portal hypertension, leading to significant morbidity and mortality.[2][3]

Etiology

The majority of cases of viral hepatitis result from hepatotropic viruses A, B, C, D, and E. It is unclear whether the hepatitis G virus (HGV) is pathogenic in humans. Other less common causes of viral hepatitis are cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus(EBV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and varicella-zoster virus (VZV). These are non-heterotropic viruses that usually do not primarily target the liver and rarely cause hepatitis in the immunocompetent state.

Hepatitis A, B, C, and D are endemic to the United States, with hepatitis A, B, and C viruses causing 90% of acute viral hepatitis and hepatitis C being the most common cause of chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis A

The hepatitis A virus (HAV) is an RNA virus from the Picornaviridae family. It is usually present in the highest concentration in the stool of infected individuals, with the greatest viral load shedding occurring during the end of the virus's incubation period. The most common mode of transmission of hepatitis A is via the fecal-oral route from contact with food, water, or objects contaminated by fecal matter from an infected individual. It is often encountered in developing countries with poor sanitation and an increased risk of fecal-oral spread. In the United States, the most common risk factor for contracting hepatitis A is international travel. Those who come in contact with infected individuals are also at risk, and the secondary infection rate for household contacts is approximately 20%.[4]

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus and a member of the Hepadnaviridae family. The composition of the viral core is nucleocapsid, hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), which surrounds hepatitis B virus DNA, and DNA polymerase. The nucleocapsid is coated with the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a viral surface polypeptide. Intact hepatitis B virus virion is known as the Dane particle. Hepatitis B virus is known to have 8 genotype variants but is not used in clinical practice to determine the severity of infection. The gene that codes for HBcAg also codes for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg).

HBV can be detected in serum, semen, vaginal mucus, saliva, and tears, even at a lower level but is not found in stool, urine, or sweat. It is transmitted parenterally and sexually when individuals come in contact with mucous membranes or body fluids of infected individuals. Intravenous drug users, men who have sex with men, healthcare workers with exposure to infected body fluids, patients who require frequent and multiple blood transfusions, people who have multiple sexual partners, prisoners, partners of HBV carriers, and persons born in endemic areas are all at high risk for contracting HBV infection.

Transfusion of blood and blood products, injection drug use with shared needles, needlesticks, or skin penetrating wounds caused by other instruments used by healthcare workers, and hemodialysis are all examples of parenteral and percutaneous exposures. The parenteral mode remains the dominant transmission mode globally and in the United States.

The virus can be transmitted perinatally as well. This occurs in infants of women who are HBeAg positive, and the infants have up to a 70% to 90% chance of infection. Up to 90% of those who become infected develop a chronic infection with HBV.[5]

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an RNA virus and is a member of the Flaviviridae family with 1 serotype but at least 6 major genotypes and more than 80 subtypes. The extensive genetic variability makes it challenging to develop a vaccine to prevent infection with HCV. Transmission can be parenteral, perinatal, and sexual. Those at the highest risk for infection include those injecting illicit drugs, as there tends to be sharing of contaminated needles. Others who are susceptible are those who require frequent blood transfusions and transplantation of organs from infected donors. Sexual and perinatal transmission is not very common.[6]

Hepatitis D

The hepatitis D virus (HDV) is an RNA virus and a single species in the Deltaviridae family. It contains the hepatitis D antigen and RNA strand and requires the presence and help of the hepatitis B virus for replication. It uses HBsAg as its envelope protein. Therefore, those who are infected with HDV also have coinfection with HBV as well. HDV has modes of transmission similar to HBV, but perinatal transmission is uncommon.[7]

Hepatitis E

The hepatitis E virus (HEV) is a non-enveloped RNA virus and a single species in the Caliciviridae family of the Herpesvirus genus. The primary transmission mode of the HEV is the fecal-oral route. Contaminated water is the most common source of infection. Person-to-person transmission is rare. However, occasionally, maternal-neonatal transmission can occur.[8]

Hepatitis G-Human Pegivirus

Hepatitis G virus ((HGV), now designated human pegivirus (HPgV-1), is an RNA virus and is a member of the Flaviviridae family. The primary mode of transmission is through infected blood and blood products, but sexual contact and vertical transmission occur as well. It is often manifested as a coinfection in those who have chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C infections. It has been implicated in patients with acute and chronic liver disease, but the evidence to date has not established it as an agent that causes hepatitis by itself.[9]

Epidemiology

Viral hepatitis is a major public health issue. Viral hepatitis infects millions of people annually, causing significant morbidity and mortality. Chronic hepatitis B and C infections can cause liver damage that includes liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and features of portal hypertension. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 1.3 million people died due to hepatitis in 2015, and 1 in 3 people in the world have had infections with either HBV or HCV. Viral hepatitis can cause up to 1.4 million deaths annually, and HBV and HCV are responsible for about 90% of those deaths. Reportedly, infection rates show that 2 billion people are infected with HBV, 185 million with HCV, and 20 million with HEV worldwide.[10][11][12]

Hepatitis A

In the US, approximately 24,900 new HAV infections are diagnosed each year. Typically, those with access to safe drinking water and sanitation services have low infection levels with HAV, with <50% of the population being endemic. Those who do not have access to safe drinking water and regions with low socioeconomic benefits have higher levels of HAV infection. HAV affects 90% of children in highly endemic regions, with more than 90% of the population being endemic.[13][14] HAV's infection rate is much higher worldwide, but only 1.5 million cases are reported annually. Children who become infected early with asymptomatic exposure acquire lifelong immunity in highly endemic countries.[15]

Hepatitis B

Estimates are that about one-third of the world's population has had an infection with HBV, and around 5% of this population remains carriers of HBV. About 25% of these carriers develop chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The documented number of global deaths annually from HBV infection is 780,000.[16][17] In the United States, approximately 22,600 new infections were diagnosed in 2018, and it is estimated that 862,000 people have chronic HBV infection.

Hepatitis C

HCV is the most prevalent cause of parenteral hepatitis worldwide. It is prevalent in 0.5% to 2% of the population around the world, with IV drug users and hemophiliacs being the most commonly affected. However, with safer screening and viral elimination techniques for blood transfusion, the incidence of transfusion-associated HCV infection is decreasing. Approximately 71 million people globally have chronic HCV infection, and this accounts for close to 400,000 deaths every year.[18][19] In the US, approximately 50,300 new HCV infections were diagnosed in 2018, and it is estimated that 2.4 million people have chronic HCV infection.

Hepatitis D

HDV infection occurs in patients who are positive for HBsAg (meaning that the person is infected with HBV and is contagious). HDV occurs as a coinfection with HBV or as a superinfection for patients with a chronic HBV infection. HDV infection is not reportable in the United States; therefore, accurate data is not readily available. It is estimated to affect 4% to 8% of cases of acute HBV and 5% of global chronic HBV patients. Approximately 18 million patients are infected with HDV globally. Prevalence remains high in South America and Africa as well among specific populations such as sex workers in Greece and Taiwan, where it has been well studied.[20]

Hepatitis E

HEV is associated with worldwide outbreaks of food and waterborne diseases. It is commonly seen in developing countries with restricted access to sanitation, clean water, and poor hygiene. About 20 million people are estimated to be infected with HEV globally, and there have been approximately 44,000 deaths due to HEV infection. In that regard, HEV carries a higher risk of mortality at about 3.3% compared to HAV infection despite a similar route of transmission and lack of chronicity.[21]

Human Pegivirus

Global infection with HPgV-1 is common, with a worldwide prevalence of around 3%, and detectable in all ethnicities. Researchers believe that 1% to 4% of blood donors worldwide are carriers of the virus. The general understanding is that around 25% of the global population carries an antibody to the virus. Infected blood products increase the prevalence of HPgV-1. Routine blood screening of donation for HPgV-1 is not done, presumably due to the lack of evidence for causing disease. Reports indicate that approximately 10% to 20% of adults with chronic HBV or HCV infection have HPgV-1, indicating that coinfection is a common occurrence. The coinfection does not increase the severity of the HBV or HCV disease. Vertical transmission of HPgV-1 from an infected mother to the newborn has been documented, but this is rare.[22]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of viral hepatitis varies with the type of hepatitis pathogen.

Hepatitis A

The incubation period of HAV is approximately 4 weeks. Acute infections with HAV are more severe, with higher mortality in adults than children. Symptoms of HAV infection include malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. The illness lasts approximately 8 weeks and is self-limiting without treatment. Relapses are not common, and the infection does not result in chronic hepatitis. Less than 1% of cases result in fulminant hepatic failure.[23]

Hepatitis B

The incubation period of an acute HBV infection is approximately 12 weeks, with most patients experiencing mild illness, which is self-limiting within 6 months—less than 1% experience fulminant hepatic failure. After acute infection resolves, most adult patients and a small percentage of infected infants develop antibodies against the HBsAg and recover fully. However, a small percentage of adult patients and the majority of infected infants develop chronic infection. Approximately 10% to 30% of carriers become symptomatic from chronic infection. They may also have extrahepatic manifestations of the disease. About 20% of chronic hepatitis patients develop cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation, while 5% develop hepatocellular carcinoma.[24]

Hepatitis C

The incubation period of HCV is approximately 8 weeks. Most cases of acute HCV infection are asymptomatic. However, approximately 55% to 85% of patients develop chronic HCV infection and liver disease; 30% of those patients progress to developing cirrhosis. Patients who are infected with HCV and have a chronic infection are at high risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of cirrhosis. Before the availability of effective treatment for this infection, an estimated 20,000 deaths annually were attributable to chronic HCV infection.[25]

Hepatitis D

The incubation period for HDV is approximately 13 weeks. HDV infection causes hepatitis only in persons with acute or chronic HBV coinfection. Symptoms are similar to acute HBV infection. Still, patients with chronic HBV infection and HDV infection tend to progress more rapidly to cirrhosis than those patients with chronic HBV infection alone. Patients already infected with HBV may develop superinfection with the HDV. Superinfection can result in fulminant hepatic failure.[20]

Hepatitis E

The incubation period for HEV is approximately 2 to 10 weeks. Acute hepatitis E virus infection is less severe compared to acute HBV infection. Still, pregnant females infected in the third trimester have a >25% mortality associated with HEV infection.[26]

Human Pegivirus

The incubation period of human pegivirus (HPgV-1) is approximately 14 to 20 days. The clinical picture can be similar to the picture of mild hepatitis infection with other hepatitis viruses, and patients can have normal or low aminotransferases without jaundice. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation is not proportional to the degree of viremia in HPgV-1, unlike HCV, where patients with high viral load can have higher alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels.[22]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of viral hepatitis can be different in each individual, depending on the type of hepatitis virus causing the infection. Patients can be entirely asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic at presentation. A small number of patients can present with rapid onset of fulminant hepatic failure.

Typically, patients with viral hepatitis go through 4 phases regardless of the type of hepatitis virus infection. Physical exam findings specific to each type of hepatitis are listed below, along with overall general findings on the physical exam.

- Phase 1 (Incubation/Viral Replication Phase) - Patients are usually asymptomatic in this phase, and laboratory studies are positive for markers of hepatitis.

- Phase 2 (Prodromal Phase) - Patients in this phase may present with anorexia, nausea, vomiting, malaise, pruritus, urticaria, arthralgias, and fatigue. These patients are often diagnosed as having gastroenteritis or other viral infections.

- Phase 3 (Icteric Phase) - Patients in this phase present with dark-colored urine and pale-colored stool. Some patients develop jaundice and right upper quadrant pain coupled with liver enlargement. Liver enzymes will be elevated.

- Phase 4 (Convalescent Phase) - Patients typically start noticing the resolution of symptoms, and laboratory studies show liver enzymes returning to normal levels.[27]

Hepatitis A

Patients who are infected with the HAV usually present with symptoms similar to gastroenteritis or a viral respiratory infection, including symptoms of fatigue, nausea, vomiting, fever, jaundice, anorexia, and dark urine. Symptoms usually start after the approximately 4-week incubation period, and they resolve spontaneously in most patients.[4]

Hepatitis B

Patients with HBV infection enter the prodromal phase after the incubation period of approximately 12 weeks and have symptoms of anorexia, malaise, and fatigue, which are the most common initial clinical symptoms. Some patients may experience right upper quadrant pain due to hepatic inflammation. A small percentage of patients experience fever, arthralgias, or rash. Once these patients progress to the icteric phase, they develop jaundice and painful hepatomegaly, dark-colored urine, and pale-colored stools. After the icteric phase, the clinical course can be variable, where some patients experience rapid symptom improvement. In contrast, others develop a prolonged illness with a slow resolution with periodic flareups. A small number of patients have rapid progression of the disease that can lead to fulminant hepatic failure over a few days to weeks.[27]

Hepatitis C

After the incubation period of approximately 8 weeks, patients infected with HCV develop symptoms similar to those of the acute infection phase in those with HBV infection. These include symptoms of anorexia, malaise, and fatigue. However, 80% of patients remain asymptomatic and do not develop jaundice.[6]

Hepatitis D

The majority of patients who have a simultaneous infection with HBV and HDV have a self-limited infection. Symptoms are similar to acute HBV infection. Chronic hepatitis B virus carriers who develop superinfection with HDV tend to have more severe acute hepatitis, and the majority of these patients will develop chronic HDV infection. Chronic infection with both HBV and HDV can lead to fulminant liver failure, severe chronic active hepatitis, and progression to cirrhosis in a majority of patients compared to those patients who only have chronic HBV infection.[28]

Hepatitis E

Patients with acute HEV infection develop an acute self-limited illness similar to HAV infection. Fulminant hepatic failure is rare, but patients with HEV infection who are pregnant have a higher mortality rate.[29]

Human Pegivirus

Patients with HPgV-1 infection can have a mild infection without jaundice, but most patients are asymptomatic. There have been few reports of fulminant and chronic hepatitis as well as hepatic fibrosis also, but it is not typical and not clearly due to HPgV-1 infection. The patient may also have an elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), but most patients infected with HPgV-1 have normal liver function tests.[22]

General Physical Examination

Physical findings vary in individual patients depending on the time of presentation. Patients may present with a low-grade fever. Patients may show signs of dehydration, especially if they have been having vomiting and loss of appetite. Findings like a dry mucous membrane, tachycardia, and delayed capillary refill can be observed. During the icteric phase, patients can have jaundiced skin or icteric sclerae and sometimes urticarial rashes. Tender hepatomegaly may be present. In advanced liver failure, signs of ascites, pedal edema, and malnutrition may be observed.[30]

Evaluation

Initial evaluation of a patient suspected of having viral hepatitis includes checking a hepatic function panel. A patient with severe disease may have elevated total bilirubin levels. Typically, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels remain in the reference range, but if elevated significantly, the clinician should also consider biliary obstruction. In advanced liver disease, prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio (INR) may be prolonged, and leukopenia and thrombocytopenia may be present. Anemia may also be present in those with advanced liver disease from gastrointestinal blood loss due to portal hypertensive sequelae (eg varices). Elevated creatinine may be an indication of the severity of the acute liver injury with secondary renal impairment. A patient who presents with altered mental status should have serum ammonia level checked, as this is usually elevated in the presence of hepatic encephalopathy.[31]

In addition to these initial routine laboratory tests, other specific tests are available to evaluate for the type of viral hepatitis as follows:

Hepatitis A

The standard test for diagnosing acute infection with HAV is the presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to HAV. IgM antibody disappears a few months after the acute infection. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody to HAV is detected in the later stages of infection. The presence of IgG antibodies to the HAV means that the patient has been infected with the HAV in the past, as recently as approximately 2 months to as long ago as several decades. Therefore, IgG antibodies to HAV do not indicate acute infection and should not be used to screen for such. Most patients with IgG antibodies to HAV have lifelong immunity against the HAV infection [23].

Hepatitis B

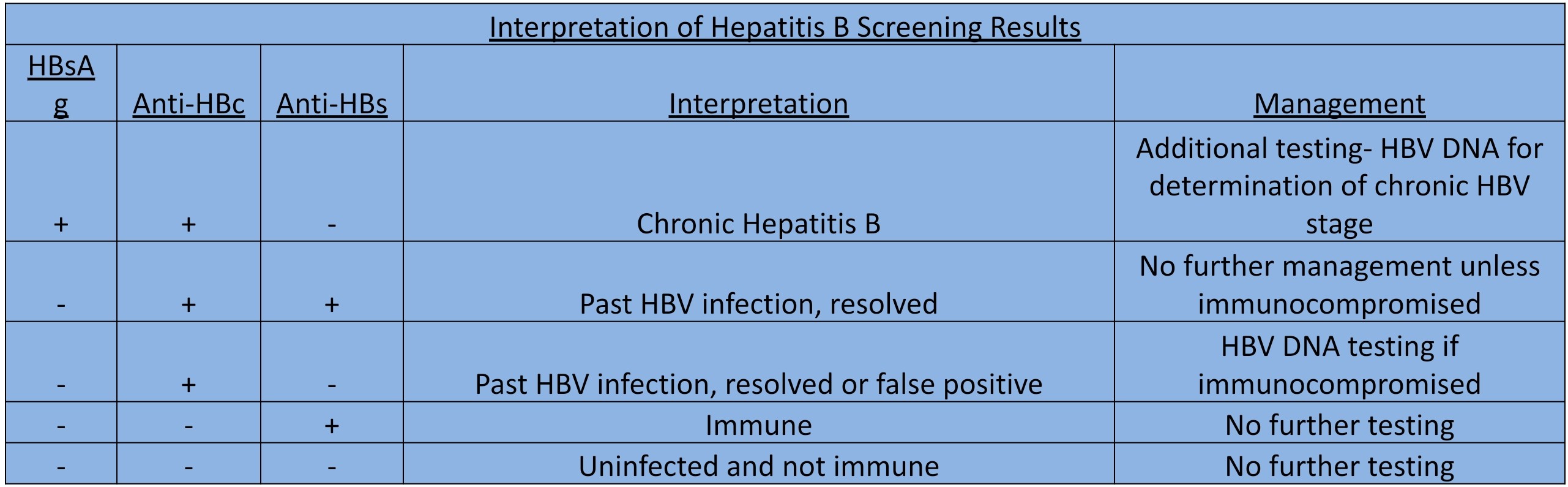

Acute hepatitis B infection

The first serum marker to appear in a patient with an acute HBV infection is the HBsAg. This antigen indicates that the patient has hepatitis B viremia, but it does not differentiate between an acute versus chronic infection, especially in the absence of symptoms. When the patient exhibits signs of acute hepatitis, the presence of HBsAg strongly suggests acute HBV infection. However, it does not rule out chronic HBV infection with a flare or superinfection. HBsAg disappears approximately 6 months after the acute infection in those patients who clear the HBV. If HBsAg remains present for more than 6 months, it indicates a chronic infection. For those who clear the hepatitis B viremia, the antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) appears. This antibody may persist for a lifetime and offers immunity to the patients from subsequent exposure to HBV.

The first antibody to appear is the IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). The presence of IgM anti-HBc also means that the patient has an acute hepatitis B virus infection, and this is required to make the diagnosis. Once the IgM anti-HBc disappears within a few weeks, IgG anti-HBc, which usually remains present for life, is detected. Total assay for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) can detect both IgM and IgG antibodies and indicates that the patient has a history of infection with HBV at some time in the past, as it remains positive both in patients who clear the virus and those who have a persistent infection.

Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) is also present early in the infection and indicates that the virus is replicating. After the viral replication diminishes, HBeAg becomes undetectable, and antibodies to HBeAg (anti-HBe) appear and can persist in the blood indefinitely (see Table. Interpretation of Hepatitis B Screening Results).

Chronic Hepatitis B infection

Patients with chronic HBV infection will have a positive HBsAg. These patients may be inactive carriers of HBV or may have active chronic hepatitis. All patients with chronic HBV infection have the presence of anti-HBc. HBeAg may or may not be present in patients with active chronic hepatitis. When present, it is indicative of viral replication.

Similarly, HBV DNA may or may not be detectable, but high levels can indicate active chronic hepatitis. Patients with chronic HBV infection usually have an absence of anti-HBs. Still, the presence of anti-HBs with positive HBsAg in patients with chronic HBV infection indicates that the antibody was unsuccessful in inducing viral clearance.

Evaluating HBV infection can be complex, and some uncommon scenarios should be considered while investigating. Testing may be negative for HBsAg and anti-HBs but positive for anti-HBc. This may occur when the result is a false positive but may also happen in the setting of the period where the patient has cleared HBsAg from the blood but anti-HBs have not yet appeared. Some patients who have cleared HBV infection but have lost the anti-HBs over time can have a negative test for HBsAg and anti-HBs but positive for anti-HBc. Also, patients infected with HBV in the remote past may develop a core mutant variant of HBV where testing is negative for HBeAg and positive for anti-HBe even though the virus is active and replicating. In the setting of the aforementioned laboratory results, checking for viral replication with HBV DNA PCR assay is generally recommended.

Patients who receive a vaccine for the hepatitis B virus develop protective anti-HBs as a response to recombinant HBsAg in the vaccine. There are no hepatitis B virus DNA or other hepatitis B virus-associated proteins in the vaccine. Therefore, patients who receive the vaccine are not positive for anti-HBc unless they have a previous infection with the hepatitis B virus.[32]

Hepatitis C

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated guidance in 2020 includes recommendations for 1-time screening for HCV infection for all adults 18 years and older and pregnant women during each pregnancy, except for instances when the prevalence of HCV infection is <0.1%.[33] Testing guidance otherwise remains the same for those with identifiable risk factors such as birth years between 1945 and 1965, blood product transfusion or organ transplant before 1992, those on chronic hemodialysis, and those with a history of injection drug use.[34][35]

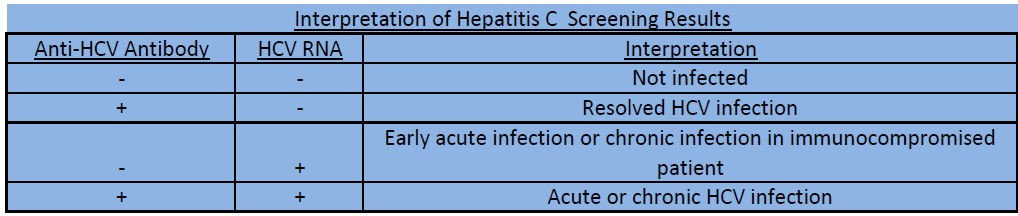

HCV exposure can be detected with antibodies to the HCV (anti-HCV). These assays can detect antibodies within 4 to 10 weeks of infection. However, anti-HCV can remain negative for a few months after an acute HCV infection, although once it appears in the blood, it generally remains present for life. Unlike anti-HBs, anti-HCV is not a protective antibody and does not offer immunity with subsequent exposure to HCV.

In the setting of a positive hepatitis C antibody test, HCV RNA testing is necessary to confirm infection. It is the most specific test for HCV infection and can detect acute infection even before antibodies develop. It is also helpful in discriminating between true infection and false-positive cases, indeterminate results, and rare cases where perinatal transmission may have taken place. (see Table. Hepatitis C Stages and Serological Markers). HCV RNA testing also provides information on viral load and HCV genotype, which can help tailor treatment and predict response to therapy. In recent years, testing for HCV genotype has become less important as some of the available treatment options are pan-genotypic (able to effectively treat infection regardless of the genotype). Knowing the genotype may be more relevant in previously failed treatment patients. During the initial evaluation, patients should be asked about prior treatment as this may play a role in medical regimen selection, and testing for viral resistance may be indicated.

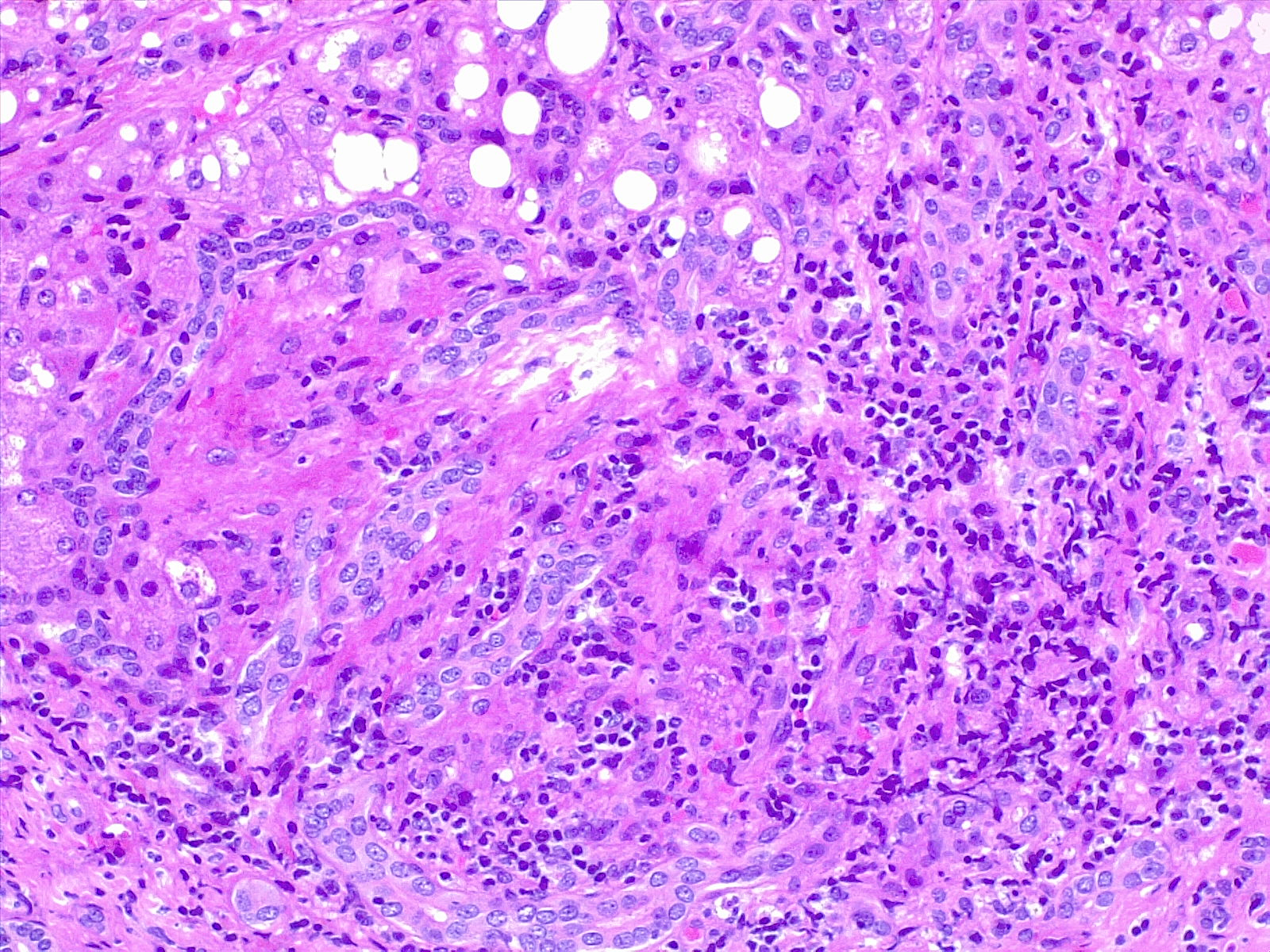

Assessment of hepatic fibrosis is an important step in evaluating those confirmed to have HCV infection. The degree of fibrosis plays a role in determining the treatment regimen and duration if there is advanced (bridging) fibrosis or cirrhosis. Fibrosis stage can be assessed by indirect markers readily found in routine blood tests such as the AST/ALT ratio, the AST to platelet ratio index (APRI), and the Fibrosis-4 score (online calculators available). Noninvasive assessment of fibrosis can also be obtained via ultrasound-based transient elastography. Liver biopsy has previously been accepted as the gold standard of fibrosis assessment. However, it is an invasive procedure with a small risk of complications not limited to bleeding and infection. In addition, the high cost and sampling error makes it a less desirable option.[36][37][38] Liver biopsy is generally reserved for cases of concern for a competing or concomitant diagnosis. (see Image. Liver Biopsy Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain).

Liver enzyme testing can indicate the presence of liver injury but is not very accurate in predicting the severity of the disease. Liver function testing can be more valuable in monitoring therapeutic response to HCV treatment, with improvement in aminotransferase levels indicating patients responding to the treatment while worsening of aminotransferase levels post HCV treatment may indicate a relapse. However, it is more common to use HCV RNA as the test of choice to monitor the response to treatment.[39][40]

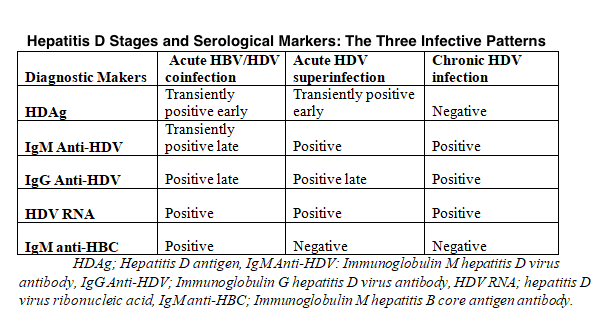

Hepatitis D

HDV infection is diagnosed by checking for IgM and IgG antibodies to the HDV (anti-HDV). IgM antibody to HbcAg (anti-HBc) must be checked to differentiate a coinfection where the patients test positive for IgM anti-HBc and superinfection, where the patients test negative for IgM anti-HBc. (see Table. Hepatitis D Stages, Serological Markers, and the Three Infective Patterns). HDV RNA test can be done but is not routinely performed.[41]

Hepatitis E

HEV infection is diagnosed by checking for IgM and IgG antibodies to the HEV (anti-HEV). Also, HEV RNA can be checked in the serum and stool of infected patients.[42]

Human Pegivirus

HPgV-1 is usually identified by checking the hepatitis G RNA PCR. Most patients develop antibodies, which are detectable after the clearance of the virus. The coexistence of HPgV-1 RNA and antibody to HPgV-1 is not common. Following the clearance of the virus, the antibody appears, and patients fully recover. Patients with persistent HPgV-1 RNA may have no biochemical or histological signs of liver disease. A small percentage of patients with chronic HPgV-1 may go on to develop liver fibrosis.[9]

Treatment / Management

The general management of acute viral hepatitis is supportive, and most individuals can be safely monitored in the outpatient setting. The infection is usually self-limited in most cases. Efforts should be made to prevent disease transmission to those in close contact with the patient.

Patients who are experiencing significant nausea or vomiting and those at greatest risk for dehydration should be admitted for intravenous fluids for hydration. Potentially hepatotoxic substances, such as alcohol, should be avoided, and medications that are metabolized through the liver, such as acetaminophen, should be used with caution. The development of rare complications like liver abscess or acute liver failure requires admission and appropriate management. Referral to specialty services such as gastroenterology or hepatology should be considered for cases that are atypical in severity or duration.

Hepatitis A

Treatment for acute HAV infection is supportive. There is no antiviral therapy for HAV infection. Patients who have intractable nausea or vomiting, as well as those who are showing signs of liver failure, should be admitted and closely monitored.[4]

Hepatitis B

Treatment of HBV infection falls into 2 categories: acute HBV infection and chronic HBV infection.

Acute hepatitis B infection

Treatment of acute HBV infection is supportive and similar to the treatment of acute HAV infection unless a more severe infection is present. Medication treatment should be considered for those who present with acute liver failure (INR >1.5, bilirubin >10 mg/dL), a severe protracted course (>4 weeks), those who are immunocompromised or have coinfection with other viruses such as HCV or HDV. If therapy is instituted, nucleoside or nucleotide analogs are generally recommended. Historically, the nucleoside analog lamivudine has been used with favorable results.[43] However, due to concerns for the development of drug resistance, another nucleoside or nucleotide analog is preferred, especially if the duration of treatment may be long-term based on the clinical scenario. Interferon therapy should be avoided due to the risk of hepatic necroinflammation and worsening liver condition and the potential adverse effects.

Chronic hepatitis B infection

The primary goal of treatment for chronic HBV infection is inhibiting viral replication. This is manifested by suppression of HBV DNA and subsequent loss of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). Secondary goals include reducing symptoms and preventing the progression of chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or developing hepatocellular carcinoma. First-line agents include pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG-IFN) and oral nucleoside or nucleotide analogs. Therapy should be selected based on individual patient profiles, patient preference, safety, efficacy, treatment cost, and drug resistance risks.

Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) treatment duration is 48 weeks for both HBeAg positive and negative chronic hepatitis. It is best used in younger patients and those with uncomplicated disease who prefer a finite treatment duration. Advantages of pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) treatment include high rates of seroconversion (loss of HBVeAg) within 1 year of therapy, loss of HBVsAg 3 years after treatment, and absence of resistance. However, it has many adverse effects, including flu-like symptoms, fatigue, weight loss, depression, and bone marrow suppression, and is generally not well-tolerated. Given these considerations, compliance remains a considerable issue. Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) treatment is contraindicated in patients who have uncontrolled psychiatric disorders, autoimmune conditions, pregnancy, decompensated cirrhosis, and blood dyscrasias.

Treatment with oral nucleoside or nucleotide analog agents is usually for an indefinite period, as withdrawal of treatment usually results in relapse. The advantages of treating with an oral regimen include ease of administration, fewer adverse effects, and an excellent safety profile. The nucleotide analog tenofovir is contraindicated in children and, in rare cases, can cause renal insufficiency, decreased bone density, Fanconi syndrome, and proximal tubular acidosis. Dose adjustment is required for these medications in patients with renal insufficiency. Patients for whom pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) is contraindicated usually tolerate these oral agents well. These agents have a potent antiviral effect, with viral suppression seen in more than 90% of patients over 5 years and subsequent fibrosis regression. The effectiveness of combination therapy with 2 oral agents or 1 oral agent with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) is not well established.[44]

Hepatitis C

Treatment of HCV infection may also be divided into acute HCV infection and chronic HCV infection.

Acute hepatitis C infection

Acute HCV infection is infrequently detected as most cases are asymptomatic. However, when detected, immediate treatment is recommended.[45] The treatment is similar to that outlined below for chronic HCV infection.

Chronic hepatitis C infection

The primary goal of treatment for chronic HCV infection is the eradication of HCV. A cure of the viral infection, also known as a sustained virologic response (SVR), is defined as the lack of viral detection in the blood 12 weeks after receiving anti-HCV therapy. Patients who achieve this endpoint have a 99% or greater chance of maintaining the cure with a later appearance of viremia attributed to reinfection.[46] Cure of the hepatitis C infection reverses liver inflammation, fibrosis, and associated changes related to portal hypertension.[47][48] There is also ample evidence that the elimination of HCV results in a decreased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma and an overall reduction in all-cause mortality.[48][49] Patients also generally report improvement in symptoms of fatigue and general well-being. Treatment of HCV infection is also an indirect path to treating extrahepatic manifestations of the virus, such as glomerulonephropathies, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The treatment regimen selection is determined by the patient's treatment history (whether naive or experienced), the degree of fibrosis or the presence of cirrhosis, and whether there are any complications of cirrhosis. Additional treatment selection considerations are given to unique patient populations such as those with HIV/HCV coinfection, decompensated cirrhosis, those after liver or kidney transplant, children, and during pregnancy.

Historically, pegylated interferon(PEG-IFN) alfa and ribavirin were the mainstay of treatment. The number of patients eligible for treatment was limited due to the potential adverse effects of interferon, such as debilitating fatigue and flu-like symptoms, bone marrow suppression with resulting thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, retinopathy, and worsening of psychiatric disorders. Ribavirin therapy carried the risk of hemolytic anemia requiring growth factor or transfusion. For eligible patients, poor tolerability limited the course of treatment, and the overall cure rate was low.

Since the introduction of the second generation of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents in 2013 and 2014, interferon-based therapy has become obsolete. It is now contraindicated in the management of HCV infection. Ribavirin use can be considered in particular circumstances, such as decompensated cirrhosis or those with viral resistance to prior therapy. With the availability of an all-oral regimen that is well tolerated and minimal pretreatment testing required, an increased number of patients are eligible for anti-HCV treatment.

For most treatment-naive patients without cirrhosis, the preferred regimen includes the pan-genotypic option of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir administered as 3 combination pills 3 times daily for 8 weeks or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir administered as 1 pill daily for 12 weeks. The choice of regimen is mainly influenced by the preference for the duration of therapy versus the number of pills and payer coverage. Both regimens have sustained virologic response (SVR) rates exceeding 95% and are well tolerated. Both combinations are safe to use in patients with renal insufficiency; glecaprevir/pibrentasvir should be avoided in decompensated cirrhosis. There are some potential severe drug interactions with either regimen, so it is necessary to run a drug interaction check before prescribing so that any necessary adjustments can be made. Additional regimens include sofosbuvir/daclatasvir (for genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4), ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (for genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6), and elbasvir/grazoprevir (for genotypes 1 and 4). These second-line agents require additional genotype and resistance testing and are indicated for patients with specific favorable clinical profiles. Sofosbuvir/daclatasvir is not available in the United States. These factors render them suboptimal options for consideration.

Those patients who are treatment-experienced, have decompensated cirrhosis, or are otherwise part of a unique population (HCV with HIV coinfection, solid organ transplant recipient, organs from HCV-viremic donors) require more complex evaluation and management and should be referred for expert care. Recommendations for management are outlined in the updated guidance by the joint association of The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.[45] Dynamic changes in recommendation can be viewed online at https://www.hcvguidelines.org/.

Hepatitis D

Patients who are coinfected with HDV and HBV usually receive treatment with pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN). Oral nucleoside and nucleotide analogs have limited or no efficacy in these patients. Pegylated interferon remains the only effective treatment. In 1 study, patients who had HDV infection with coexisting HIV infection had therapy with tenofovir, which showed good efficacy. Still, the exact mechanism of this efficacy is unknown, and more studies are required.[50]

Hepatitis E

Treatment for acute HEV infection is supportive. Immunosuppressed patients and solid organ transplant recipients can develop chronic HEV infection and can have treatment with ribavirin. Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) has been used successfully but has been associated with many adverse effects, such as cholestasis.[51]

Human Pegivirus

There is currently no recommended treatment for HPgV-1. Patients who develop liver cirrhosis have treatment with similar treatment modalities used to treat cirrhosis of any other etiology.[22]

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of viral hepatitis can be nonspecific, so other etiologies of hepatitis and liver disorders may present with similar symptoms and signs commonly found in patients with viral hepatitis. Patients with acute and chronic active viral hepatitis infections may present with malaise, fatigue, low-grade fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. Physical exam may be unremarkable, or there may be the presence of right upper quadrant tenderness with hepatomegaly, urticarial rash, and possibly evidence of dehydration. In advanced stages of liver disease from chronic viral hepatitis, patients may present with hematemesis, ascites, pedal edema, or hepatic encephalopathy.

Liver and non-liver-related disorders with similar presentation to viral hepatitis include drug-induced hepatitis, viral or bacterial gastroenteritis, acute cholecystitis, acute cholelithiasis, hereditary hemochromatosis, and malignancies such as pancreatic cancer, lymphoma, hepatocellular cancer, and peptic ulcer disease. Patients with severe congestive heart failure can present with pedal edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly due to hepatic congestion. Patients who present with symptoms of end-stage liver disease (variceal bleeding, volume overload, and encephalopathy) may have liver decompensation from etiologies other than chronic viral hepatitis, such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and autoimmune or alcohol-related hepatitis.

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disease that disrupts the body's iron regulation, and excess iron becomes deposited in various organs of the body, including the liver. Diagnosis is usually made by checking serum iron, serum ferritin, and serum transferrin levels. A liver biopsy may become necessary to evaluate the degree of fibrosis and to differentiate it from other disorders of the liver, including viral or autoimmune hepatitis. Patients can present with joint pain, and some patients complain of pain in the knuckles of the first 2 fingers, called the "iron fist" sign. This sign is specific to hereditary hemochromatosis but is not present in all the patients.[52]

Patients with drug-induced hepatitis and congenital hepatopathies can also have a similar presentation, and a careful history is integral while evaluating the patients. Drug-induced liver injuries have become more common, and more than a thousand drugs have been identified, with studies underway to find out more about them. Patients with drug-induced liver injuries can be completely asymptomatic with only lab abnormalities of elevated aminotransferases or with acute or chronic hepatitis or acute liver failure. Drug-induced liver injuries remain 1 of the biggest causes of emergency liver transplants. The unregulated use of herbal and dietary supplements has created a new challenge to identify and treat patients promptly.[53]

To differentiate the type of hepatitis, a careful history, laboratory studies, and, when necessary, a liver biopsy should be obtained. The evaluation section of this review provides further information on how to diagnose and differentiate these conditions.

The differential diagnoses for viral hepatitis are as follows:

- Liver abscess

- Hepatocellular cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

- Drug-induced hepatitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Acute cholangitis

- Acute cholecystitis and biliary colic

- Pancreatitis

- Gastroenteritis

- Cholelithiasis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Small-bowel obstruction

Prognosis

The prognosis of viral hepatitis depends on the type of virus causing the infection.

HAV infection is usually a mild self-limiting illness. Patients infected with HAV develop lifelong immunity against subsequent infection from HAV. Overall, mortality is low, and complications, including relapse, jaundice, and fulminant liver failure, are rare. Patients who are immunocompromised, older adults, and young children are at higher risk compared to healthy adults.[4]

Patients with HBV infection are at risk of developing chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma as a consequence. Fulminant hepatic failure happens in about 0.5% to 1% of the patients with HBV infection. However, when there is fulminant hepatic failure, the mortality rate is approximately 80%. Chronic liver disease from chronic HBV infection is responsible for about 650,000 fatalities per year globally.[54]

Patients infected with HCV will develop a chronic infection in 50% to 60% of cases. These patients are at risk of progression to cirrhosis and developing hepatocellular carcinoma. Chronic HCV infection was previously a leading cause of liver transplantation. The hepatitis C-related mortality rate in the United States increased annually until 2013. With the introduction of highly effective anti-HCV therapy in 2013 and 2014, the mortality rate and the need for liver transplants have declined significantly. However, mortality remains elevated in developing countries.[55]

Patients with chronic HBV infection who later acquire superimposed HDV infection generally develop chronic HDV infection. This typically results in the development of more severe hepatitis compared to patients who only have chronic HBV infection. Many of the coinfected patients will progress to end-stage liver disease and cirrhosis.[56]

HEV infection is a mild self-limiting illness comparable to HAV infection. However, a mortality rate of 15% to 25% may be seen in pregnant patients. The exact mechanism of how it triggers such severe infection with a resulting high mortality rate in pregnant patients is not clear.[57]

With human pegivirus-1, most patients are asymptomatic in acute infection with normal aminotransferase levels. Fulminant hepatic failure and chronic infections are rare, and often, the etiology of HPgV-1 is in question. Although coinfection with HBV and HCV is common, it does not increase the severity of the disease.[9]

Complications

Complications of viral hepatitis include chronic infection with chronic active hepatitis, acute or subacute hepatic necrosis, liver failure, cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HBV or HCV infection. The complications of viral hepatitis can be treated in some cases with antiviral therapy helpful in eradicating or ameliorating the extrahepatic complications of viral hepatitis.

Patients with chronic HBV infection are at risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma, even in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatitis B-associated hepatocellular carcinoma is responsible for 45% of primary liver cancer worldwide. About 1% of patients can also develop fulminant hepatic failure, and the mortality rate is approximately 80% in those patients.

About >50% of patients infected with HCV develop chronic infection, with approximately 20% of those patients developing cirrhosis, and some will eventually progress to hepatocellular carcinoma. The complications of cirrhosis include hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertension, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, and progression to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Liver-directed treatment of complications is, in large part, related to the complications of cirrhosis and is best managed by experts in cirrhosis care. Liver transplantation is curative for the complications of cirrhosis in eligible patients.

For patients who develop hepatic encephalopathy, the first-line therapy is oral lactulose. When symptoms are uncontrolled by lactulose, rifaximin is FDA-approved for addition to lactulose therapy. The administration of somatostatin or octreotide and prophylactic antibiotics is the standard of care for active gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients with variceal bleeding require immediate resuscitation, protection of the airway, endoscopy with sclerotherapy, or band ligation of the varices. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement is rescue therapy for variceal bleeding not controlled endoscopically.

Ascites is initially managed with restriction of dietary sodium intake of 2000 mg daily followed by oral diuretic agents (commonly spironolactone and furosemide). Paracentesis is reserved for those uncontrolled by initial measures or who are severely symptomatic and in need of immediate relief. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) can also be considered for ascites otherwise challenging to control. Ascites may be complicated by the development of spontaneous bacterial infection termed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Treatment generally involves intravenous antibiotics and requires subsequent antibiotic maintenance for secondary prophylaxis against repeat infection.

Patients who develop hepatocellular carcinoma may be candidates for locally directed therapies (e.g., radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization), systemic chemotherapy, or surgical resection in carefully selected patients.

Patients with chronic HCV infection may also develop extrahepatic complications, including coagulopathies and cryoglobulinemia, which can lead to rash, vasculitis, and glomerulonephritis secondary to the deposition of immune complexes in the small vessels. Other associated disorders include non-Hodgkin lymphoma, focal lymphocytic sialadenitis, autoimmune thyroiditis, porphyria cutanea tarda, and lichen planus.[58] Correction of severe coagulopathy can be considered in the setting of active bleeding or the need for invasive procedures such as placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or other surgeries.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is crucial in preventing and controlling viral hepatitis. Patients with chronic viral hepatitis should be educated on the risk and mode of transmission, as well as the need for routine monitoring to assess the necessity for treatment. Patients who have evidence of disease progression, especially with evidence of cirrhosis with or without complications, should be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist promptly. Instruction should be provided to all patients about not sharing items such as toothbrushes, razors, or needles that can result in blood exposure and, therefore, transmission to others. Fruits and vegetables should be eaten after being cooked or washed and peeled. Patients traveling to endemic areas should be advised not to drink untreated water or ingest shellfish or raw seafood. Patients should avoid using hepatotoxic agents such as alcohol. Acetaminophen, which is metabolized through the liver, should be used with caution but avoided in the setting of severe liver injury. Patients with hepatitis A infection should not handle food for others until they stop shedding the virus.

All pregnant women should be screened for HBV infection and HIV infection. Treatment of HBV during pregnancy will depend on the viral load and HIV status. Neonates born to mothers with chronic HBV infection should receive immunoglobulin and HBV vaccination according to standard protocol to prevent the transmission of the virus.

Healthcare workers should maintain strict universal infection control practices. Those workers at risk of viral hepatitis infection should undergo vaccination against HAV and HBV. Where there is a risk of infection with HCV, appropriate health education, testing, and treatment, if needed, should be offered. Healthcare professionals should be educated on identifying individuals at risk for viral hepatitis and offer testing to treat if infection is identified. While it is important to identify those at increased risk of viral hepatitis infection, healthcare workers should be educated regarding the recommendations for universal screening for HBV and HCV for all adults aged 18 and older in the United States.

Vaccinations are available for the prevention of some types of hepatitis; preventing hepatitis is much easier than treating hepatitis. Viral hepatitis is preventable with vaccination.

Hepatitis A

Individuals who provide services to adults with a high risk for HAV infection (eg, non-residential group homes) and those traveling to areas where HAV is endemic should be offered the HAV vaccine 1 month before anticipated exposure risk. Other individuals who should be offered the HAV vaccine are hemophiliacs whether or not they receive clotting products, those who use illicit drugs, men who have sex with men, patients with chronic liver disease, patients who are awaiting liver transplant or are recipients of a liver transplant, and individuals who work with hepatitis virus-infected primates in laboratories.

Patients can receive inactivated HAV vaccine through the intramuscular route, with a booster dose recommended after 6 months. Patients exposed to HAV can also be given postexposure prophylaxis with hepatitis A immunoglobulin and should have it within 48 hours of exposure for higher effectiveness. Typically, it is recommended for individuals in close contact with the patients of HAV infection at home or in daycare centers.[59]

Hepatitis B

The HBV vaccine is recommended for all infants as a part of the routine immunization schedule. It should also be given to adults at high risk of infection, including patients on dialysis, healthcare workers who are at risk of exposure to blood and body fluids, people with sexual partners who have HBV infection, sexually active persons who are not in a long-term monogamous relationship, persons who are being evaluated or treated for sexually transmitted diseases, men who have sex with men, individuals who share needles or syringes, household contacts of individuals who have HBV infection, residents and staff of facilities for developmentally disabled persons and in correctional facilities. Patients with chronic liver disease should also be offered the HBV vaccine. Neonates who are born to mothers who have HBV infection should be given HBV vaccination within 12 hours of birth to prevent the transmission of the virus. Plasma-derived or recombinant HBV vaccines are highly effective, with more than a 95% seroconversion rate. Infants are given initial vaccination at birth with repeat vaccination at 1 to 2 months and 6 to 18 months. For the adults, after the initial vaccination, it is repeated at 1 month and 6 months. Some clinicians recommend a booster dose at 5 to 10 years. Individuals can also receive postexposure prophylaxis with hepatitis B immunoglobulin. Patients requiring frequent transfusion of blood products or factor concentrates, such as patients with hemophilia, should also receive the vaccination. However, the higher usage of recombinant factors and better techniques for viral detection have decreased the risk of infection significantly.[60]

Hepatitis C

Vaccines against HCV are currently unavailable, and immunoglobulin has not been proven effective in preventing transmission. It is, therefore, of high importance to put infection control practices in place to prevent the contamination of blood, organs, and semen and prevent the transmission of the virus into donor pools with better screening and improved viral elimination techniques.[60] Pregnant mothers testing positive for HCV should be offered treatment after delivery. Infants born to mothers with HCV infection should have testing done at 2 months and then at 18 months to detect infection.

Hepatitis D

Since HDV occurs as a coinfection when HBV infection is present, transmission can be prevented by immunizing patients against HBV. Currently, it is not possible to prevent HDV superinfection in patients with chronic HBV infection.

Hepatitis E

A vaccine for HEV infection does not exist at this time, and immunoglobulin administration does not prevent the disease.[61]

Human Pegivirus

Patients who are transplant recipients or get frequent transfusions, injection drug users, hemodialysis patients, and men who have sex with men are the groups that are at increased risk. However, there is currently no vaccine available for hepatitis G.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Viral hepatitis is a complex disease requiring an interprofessional approach from healthcare professionals. Strategies to prevent viral hepatitis through patient education and vaccination are essential, and closer monitoring for disease progression and complications is paramount. To enhance patient-centered care, these strategies require significant interprofessional communication and care coordination by physicians, including primary care physicians and specialists, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals. The healthcare team must work closely with the patient to ensure they understand their disease, comply with medications, vaccines, and other precautions, and note progress or lack thereof. Pharmacists are a crucial part of the team by ensuring the medications at the correct dose are in the therapy regimen and that there are no drug-drug interactions. Any issues noted by any member of the interprofessional healthcare team should be documented and shared promptly. These measures will help improve patient outcomes, improve patient safety, and enhance team performance.