Introduction

Howell-Jolly bodies are nuclear remnants found in red blood cells (erythrocytes) under various pathological states. They most commonly present in patients with absent or impaired function of the spleen; this is because one of the spleen’s functions is to filter deranged blood cells and remove the intracellular inclusions left by the erythrocyte precursors. William Howell and Justin Jolly in the early 1900s first discovered Howell-Jolly bodies in the early 1900s.[1]

Issues of Concern

Howell-Jolly bodies appear in peripheral blood smears in patients with absent or deficient spleen function. They are pathognomonic for splenic dysfunction, but can be found in a long list of disorders: post-splenectomy, sepsis, congenital disorders, sickle cell hemoglobinopathies, alcoholism, lupus and other autoimmune disorders, and post-bone marrow transplantation. Other less common causes are gastrointestinal diseases (Celiac, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases), neoplastic disorders, splenic vascular thrombosis, amyloidosis, elderly, post-methyldopa treatment, and post-high-dose corticosteroid treatment.[2][3] Detection and counting of Howell-Jolly bodies do not reflect an accurate assessment of spleen function; however, they often present concurrently.[4]

Other erythrocyte inclusions exist and should be distinguished from Howell-Jolly bodies. These include basophilic stippling, Pappenheimer bodies, Heinz bodies, and Howell-Jolly body-like inclusions in neutrophils. These will be discussed further in clinical significance.

Structure

Howell-Jolly bodies are DNA-containing inclusions found after erythrocyte maturation. The composition of the DNA is still unknown to this day. However, studies show that they are of centromeric origin. Smaller Howell-Jolly bodies contain nuclear material from 1 to 2 centromeres, and larger Howell-Jolly bodies contain nuclear fragments from up to 8 centromeres. Centromeres from chromosomes 1, 5, 7, 8, and 18 are the most frequently observed fragments. The average size of Howell-Jolly bodies is 0.73 micrometers.[5]

Function

Howell-Jolly bodies do not have any true inherit functions and solely act as a sign of an underlying pathologic process that involves the spleen.

Tissue Preparation

Specimens are prepared by collecting whole blood from a patient, placing the sample in a purple top tube with appropriate anticoagulant (potassium EDTA). The sample is then smeared on a microscope slide and prepared with a Wright-Giemsa stain for examination under a light microscope.

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

There are no specific histochemical markers for detecting Howell-Jolly bodies. However, there have been recent advances in the detection and quantification of erythrocyte chromosomal fragments with flow cytometry. Sample preparation is with an RNase/antibody solution and anti-CD71 fluorescein isothiocyanate to detect young reticulocytes. This process is not common in medical practice.[6]

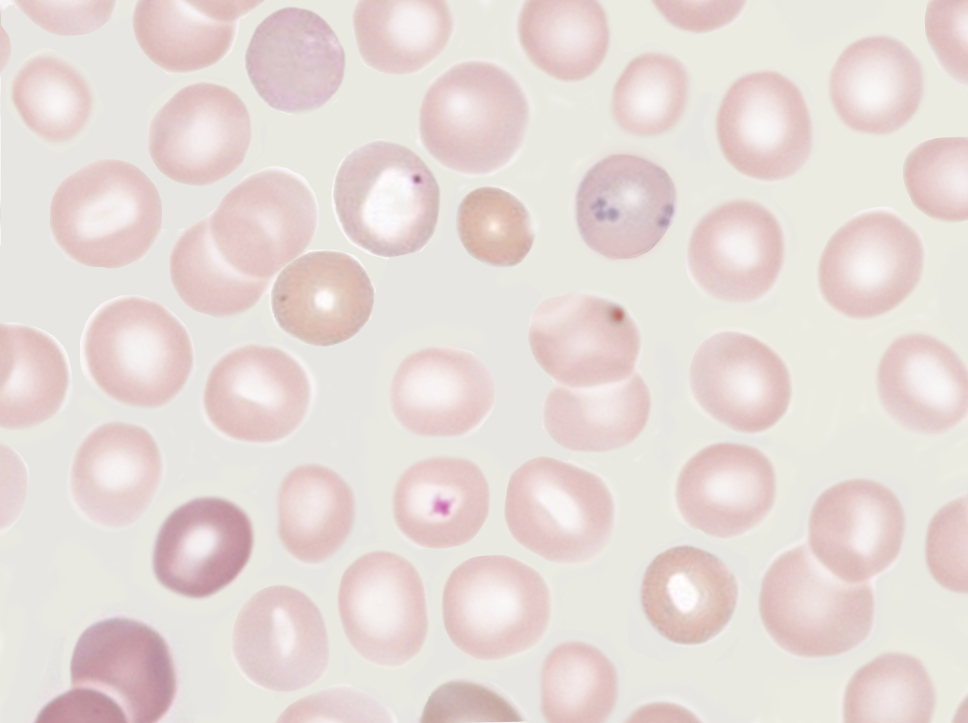

Microscopy, Light

The nuclear fragments appear as small but strongly basophilic (purple) dots inside the eosinophilic (pink) red blood cells. They are normally solitary in each red blood cell. They can be confused with overlapping platelets, but they do not have the “halo” that typically overlies platelets.[7]

Microscopy, Electron

Although performing electron microscopy is not routine for examining peripheral blood smears, a study in 1973 used electron microscopy to show that Howell-Jolly bodies are intracellular and found below the erythrocyte membrane.[8]

Pathophysiology

Erythrocytes undergo many important changes and growth to become a functional cell for oxygen transportation. Erythropoiesis (RBC production and maturation) begins as a hematopoietic stem cell in the bone marrow. This cell can further differentiate into proerythroblasts and later erythroblasts (normoblasts) with the help of specific transcription factors. The enucleation process begins in the erythroblast and occurs via fragmentation and expulsion. Another supplemental theory is that nuclear fragments are a result of the separation of chromosomes during mitosis.

There are two other main mechanisms for removing nuclear fragments from red blood cells. The first is from the spleen. Its function is to remove the inclusions without destroying the cells in which they are confined, which may occur by cell fragmentation. The second process occurs while the normoblast exits the bone marrow through the endothelial pores.

With these theories in mind, one can understand why Holly-Jolly bodies are present in patients with pathologies of nuclear maturation (megaloblastic anemia), and splenic dysfunction.[1]

Clinical Significance

Hyposplenism correlates with a long list of different disorders. The most common causes are post-splenectomy, sepsis, congenital disorders (congenital asplenia, Ivemark’s syndrome, Stormorken syndrome, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy [APECED] syndrome, cyanotic heart disease, prematurity), sickle hemoglobinopathies, alcoholism, lupus, and post-bone marrow transplantation. Other less common causes are gastrointestinal diseases (celiac disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease), other autoimmune disorders, neoplastic disorders, splenic vascular thrombosis, amyloidosis, elderly, post-methyldopa treatment, and post-high-dose corticosteroid treatment.[3] Splenic dysfunction leaves patients susceptible to infections by encapsulated bacterial organisms (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis) because splenic macrophages are responsible for removing encapsulated bacteria. They should receive prophylactic vaccines (pneumococcal, Hib, meningococcal).

Two of the most common ways of measuring splenic function are liver-spleen scintigraphy and measuring/counting of Howell-Jolly bodies on peripheral smears. Studies show that there is discordance between the two tests, and there is considerable variation in results when considering several diseases. There is no clear answer for which test is better for qualifying splenic function, but taking spleen size into account has been shown to add concordance between the results of the two tests.[9]

Howell-Jolly bodies are pathognomonic for splenic dysfunction. The nuclear remnants do not have a specific function or role. However, they only act as a clue to an underlying pathological process. Howell-Jolly bodies are one of many types of inclusions found in circulating erythrocytes. They appear to look similar to Heinz bodies, which present in patients with G6PD deficiency, or other hemolytic anemias. They are also confused with basophilic stippling, which is a process most attributed to lead toxicity, but can occur in other conditions such as thalassemia, sickle cell disease, vitamin B12/folate deficiency, and myelodysplastic syndrome. More recent studies have found Howell-Jolly body-like inclusions in neutrophils and other important immune cells. They occur in immunocompromised states such as HIV, post-transplant immunosuppression, and post-chemotherapy.[10] Lastly, Howell-Jolly bodies must be distinguished from Pappenheimer bodies. Pappenheimer bodies are similar-appearing red blood cell inclusions that appear in asplenic patients. They are basophilic-staining granules composed of iron compounds (ferritin aggregates). These are most common in diseases such as sideroblastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and sickle cell disease.[11]

Another crucial clinical fact to consider is that several studies have shown that Howell-Jolly bodies can interfere with calculating reticulocyte count. This factor is important in the evaluation of bone marrow erythropoiesis and hemolytic anemias.[12]