Continuing Education Activity

Up to 5% of fractures involve the humeral area. In the young, this injury is typically due to high-energy trauma, as in motor vehicular accidents. In contrast, older patients can fracture this bone even at low impact. Conservative and surgical treatments are available for humeral shaft fractures, though these injuries may cause complications after therapy. Unsuccessful treatment may lead to nonunion, malunion, patient dissatisfaction, and functional limitations that can compromise one's quality of life.

This activity presents the causes of humeral shaft fractures and the roles of the interprofessional team in diagnosing and managing this condition. Orthopedic treatment options for these injuries are also discussed.

Objectives:

Identify at-risk populations for humeral shaft fractures and the likely injury mechanisms in each group.

Describe the different presentations of humeral shaft fractures.

Determine the acceptable humeral shaft fracture tolerances and the appropriate treatment options for each.

Implement strategies for improving interprofessional care coordination and communication to ensure the best outcomes after humeral shaft fracture treatment and rehabilitation.

Introduction

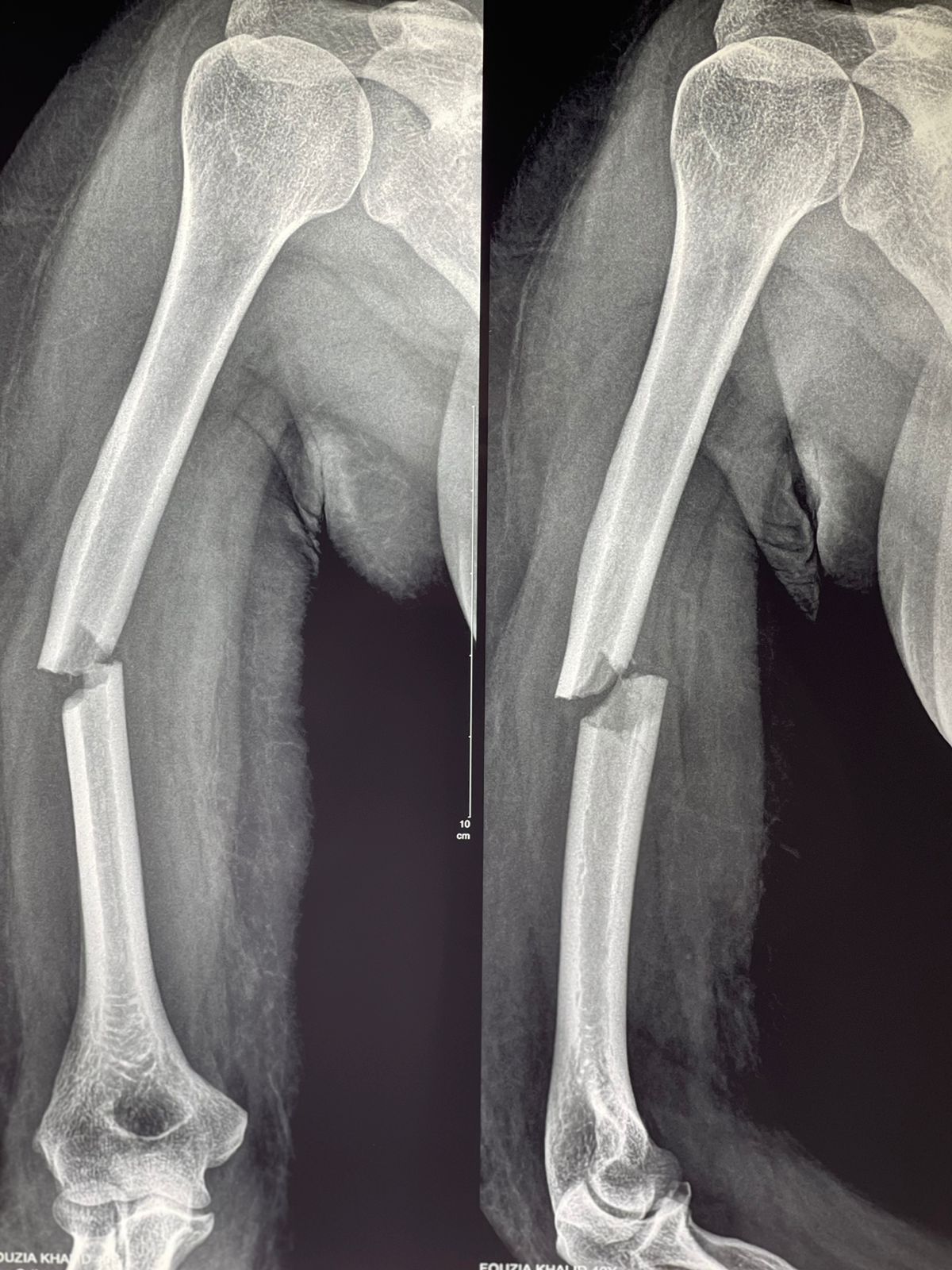

The humerus (arm bone) is the upper arm's only long bone. Humeral shaft fractures comprise 1-5% of all bony fractures (see Image. Oblique Humeral Shaft Fracture). These injuries have a bimodal age distribution. In young people, humeral shaft fractures are mostly caused by high-energy trauma. In older individuals, the damage may be caused by a low-impact force.[1]

The humerus articulates with the scapula proximally and the radius and ulna distally. The proximal humerus has a head, neck, and greater and lesser tubercles. The humeral head articulates with the scapula's glenoid fossa, forming the scapulohumeral joint, also known as the glenohumeral or shoulder joint. The anatomical neck of the humerus is the region around the humeral head proximal to the greater and lesser tubercles. The greater tubercle is the lateral border of the arm bone. The lesser tubercle is the arm bone's anterior projection. The intertubercular (bicipital) groove is the furrow between these tubercles.

The surgical neck of the humerus is the narrow portion distal to the tubercles. This site is one of the most commonly involved locations in humeral shaft fractures.

The deltoid tuberosity on the arm bone's lateral aspect is the deltoid's distal attachment site. The radial groove is a depression running posterolaterally on the middle third of the humerus. Middle-third humeral fractures can injure the radial nerve and profunda brachii artery, which pass in the radial groove.

The humerus widens inferiorly, forming the lateral and medial supracondylar ridges. The lateral and medial epicondyles form at the distal end of the humerus. The humeral condyle comprises the lateral and medial epicondyles, the capitulum, the trochlea, and the olecranon, coronoid, and radial fossae.

The arm has 2 compartments. The anterior compartment contains the brachial artery and vein, biceps brachii, brachialis, coracobrachialis, and musculocutaneous, median, and ulnar nerves. The posterior compartment houses all 3 muscle bellies of the triceps and the radial nerve.[2]

Historically, most humeral shaft fractures have been treated nonoperatively, especially with the development of the functional brace by Sarmiento et al.[3] However, some humeral shaft fractures require early surgical intervention for better outcomes.[4]

Etiology

Humeral shaft fractures may result from various mechanisms, which may be classified as high-impact or low-impact. High-force trauma can arise from direct blows to the arm, typically due to motor vehicular crashes, sports activities, work-related accidents, and physical assault.

Low-impact humeral shaft fractures result from indirect trauma, as when landing on an outstretched arm. The force comes from a distant point of impact and is transmitted along the humerus. Older individuals and people with an underlying bone disease are susceptible to this kind of injury.

Understanding the humeral fracture mechanism is important for diagnosing and managing the condition and can help detect associated injuries.

Epidemiology

As mentioned, humeral shaft fractures comprise 1-5% of all fractures. These injuries have a bimodal age distribution, with common etiologies varying by age group. The vulnerable populations are individuals in the 3rd and 7th decades of life, with high-force trauma more common in younger people and low-impact injuries more frequent in older patients.

Approximately 60% of humeral shaft fractures are seen in patients older than 50 years. Around 70% of patients with humeral shaft fractures younger than 50 years are men, while around 70% of patients older than 50 years are women.

The most commonly fractured humeral site is the middle third, comprising 60% of humeral shaft fractures.[5]

Pathophysiology

Proximal-third humeral fractures frequently involve the surgical neck and are more common among older individuals (see Image. Fracture Of The Proximal Third Of The Humerus). Falling on an outstretched hand can push the distal part of the bone into the proximal fragment, resulting in an impacted fracture. The axillary nerve is a vital structure that may be injured along with the surgical neck of the humerus. Impacted fractures in this area can remain stable and produce little pain. However, a concomitant axillary nerve injury may lead to weakening of the teres minor and deltoid and reduced sensation in the shoulder area.

The middle third of the humerus is a common site for transverse and spiral fractures. Transverse fractures in this region usually result from a direct blow, with the deltoid pulling the proximal fragment laterally. In contrast, spiral fractures commonly arise from falling on an outstretched hand. Severe injuries can damage the radial nerve and profunda brachii, which lie in the radial groove in this region. Radial nerve lesions at this level manifest as wrist drop, weak finger extension at the metacarpophalangeal joints, and inability to extend and abduct the thumb. Sensory loss may occur in the dorsal aspect of the forearm, digits 1 to 3, and radial half of the 4th digit. Profunda brachii injury can cause forearm and hand ischemia.

Middle-third humeral fractures usually heal well because of good periosteal vascularity and the muscles stabilizing the area. Up to 90% of patients with a closed humeral shaft fracture and concomitant radial nerve injury experience a resolution of neuropraxia within 3 to 4 months following the injury.[21][22]

Fractures of the distal third of the humerus result from a severe fall on the flexed elbow. The median and ulnar nerves may be damaged following this kind of injury. Median nerve lesions may produce weakness of the extrinsic lateral hand flexors, thenar muscles, and lateral 2 lumbricals. Sensory changes may be observed in the volar portion of the lateral 3-1/2 digits. Ulnar nerve lesions weaken the extrinsic medial hand flexors and the rest of the intrinsic hand muscles. Sensory weakness in the volar aspect of the medial 1-1/2 digits may also occur.

A Holsten-Lewis fracture is a fracture of the distal third of the humerus with associated radial nerve palsy.

History and Physical

The most common symptom of a humeral shaft fracture is pain on the injured site. The mechanism of injury may prompt the provider to investigate beyond the presenting complaint. High-energy trauma usually causes multiple injuries, requiring formal trauma team activation and complete patient evaluation. Low-force trauma should raise suspicion of pathologic fractures from conditions like osteoporosis.

Upper arm deformity, swelling, or ecchymosis may be noted on physical examination. Fractures distal to the deltoid insertion cause the arm to be in varus. The skin must be examined for evidence of an open fracture. Alternatively, skin tenting may be found overlying the broken bone segments, signifying an impending open fracture. The evaluation must be completed by examining easily missed sites like the axilla and posterior arm.

The neurovascular examination may be performed in a proximodistal approach to ensure thoroughness. Radial nerve palsies are seen in 2-17% of patients with humeral shaft fractures, presenting as wrist and finger extensor weakness.[6]

An initial assessment of the brachial artery's integrity may be performed by examining the distal radial and ulnar pulses and capillary refill at baseline. Neurovascular status deviation from the baseline after the initial intervention warrants diagnostic imaging and, possibly, surgical correction.

Evaluation

A complete assessment of patients with suspected humeral shaft fractures includes an initial neurovascular examination. Radiographs of the humerus must be obtained once all the patients' emergent needs are met. The images must include the shoulder and elbow joints and have at least 2 views. Associated injuries, especially on the ipsilateral side, must likewise be documented by radiography. Information about the last meal time, blood thinner use, and comorbidities must be obtained from patients being considered for immediate surgery. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) should be ordered for suspected vascular injuries. Radial nerve palsy, if present, should also be documented before any reduction maneuvers.

Humerus radiography should allow examiners to assess the injury's scope and characteristics. Typical anteroposterior and lateral (APL) humeral views include the shoulder and elbow joints and the long bone itself. The intact shoulder joint has the humeral head articulating with the glenoid fossa. The humerus widens distally, articulating with the radius (lateral) and ulna (medial) at the elbow joint.

The humeral shaft is the cylindrical portion of the long bone, which is traditionally divided into the proximal, middle, and distal thirds to localize the fracture better. The nature of the humeral shaft fracture—whether transverse, oblique, spiral, edge, or comminuted—must be documented, as this dictates the surgical technique.

Decisions regarding the initial and definitive treatments must be based on the radiographic images obtained. Absolute indications for immediate surgical fixation include open fractures, fractures requiring vascular repair, floating elbow arising from an ipsilateral forearm fracture, brachial plexus injury, compartment syndrome, and periprosthetic fractures. Factors like bilateral or multiple limb involvement, fracture complexity, and the presence of significant soft tissue disruption must also be considered when evaluating the need for emergent surgery. Closed, isolated injuries may be immobilized temporarily and re-evaluated for further treatment on an outpatient basis if the neurovascular status is normal.[7]

Treatment / Management

Arm Injuries That Can Be Managed Conservatively

Closed fractures have intact skin surrounding the bone fragments. Closed reduction is the appropriate initial treatment for these injuries, and it typically requires traction and the application of other forces that reduce the deformity. Initial splinting or casting helps immobilize the bone after closed reduction, producing an acceptable tolerance. Closed reduction, splinting, and casting require multiple providers for adequate reduction.

Acceptable tolerances of the humeral shaft are 20° of angulation in the anteroposterior plane, 30° of varus or valgus, 15° of malrotation, and up to 3 cm of shortening. These characteristics are enough to maintain long-term upper extremity function, even without operative treatment.[8]

The humeral shaft may remain in apparent valgus in patients with a larger body habitus, as the chest may push it back in varus over time. Initial immobilization may be performed using a coaptation splint or a hanging arm cast. A coaptation splint is a U-shaped splint formed by applying the malleable material on the axilla medially, around the elbow joint distally, and up the acromioclavicular joint superolaterally. In contrast, a hanging-arm cast suspends the arm and cast in a sling with the elbow held at 90°. The weight of the cast and the patient's arm creates arm muscle tension that improves fracture alignment.

Patients with isolated humeral injuries usually remain stable after immobilization. They may be discharged and instructed to follow up as outpatients once neurovascular integrity is confirmed.

The splint or cast may be converted into a Sarmiento or functional brace 7 to 10 days after the initial reduction. This brace is made from a prefabricated hard shell that runs on either side of the arm. The resulting soft tissue compression prevents angular and rotational forces from disrupting bone alignment.[9] Approximately 94% of conservatively managed closed fractures achieve bone union and functional alignment in 10.7 weeks on average. Interval radiographs help document the healing process during outpatient follow-up. Weight-bearing exercises may start once bone union is achieved. Physical therapy helps patients regain strength and function.

Arm Injuries Requiring Surgery

The most emergent arm injuries include open fractures, fractures with associated neurovascular injuries, floating elbow, and compartment syndrome. These conditions require different approaches.

Open fractures have skin breaks overlying the fracture site, exposing the inner structures to microbes. Intravenous antibiotics and tetanus immunization are essential. Bedside irrigation with wet-to-dry dressings must be performed before immobilization. Early plastic surgery is recommended if large soft-tissue defects are present.

Associated vascular injuries must be evaluated by CTA. The orthopedic and vascular surgery teams must work closely to prevent limb ischemia and necrosis. Orthopedic fixation, which vigorously manipulates the tissues, usually precedes vascular repair unless the latter is more urgently needed. Brachial plexus involvement is also initially treated with fracture immobilization, which allows proper localization of the nerve damage. Radial nerve palsy resulting in wrist drop requires a cock-up wrist splint.

A floating elbow arises from ipsilateral forearm fractures secondary to high-impact trauma. The initial approach consists of forearm and arm immobilization. The limb's neurovascular status must be monitored frequently as the condition puts patients at risk for compartment syndrome.[10] Compartment syndrome requires immediate surgical intervention.

Surgical Techniques For Humeral Shaft Fractures

Surgical humeral shaft reduction is accomplished in several ways. The techniques include external fixation, intramedullary nail fixation, and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

Polytrauma makes patients poor surgical candidates. External fixation of humeral shaft fractures is indicated in such cases. The fractures are reduced as best as possible and held in place by connectors and pins placed outside the skin. The implants must be positioned carefully to prevent injuring vital arm structures. Proximally, these implants must avoid the axillary nerve and biceps tendons and be secured anterolaterally. Distally, the implants must avoid the radial nerve. Large incisions may be necessary to visualize the vital arm structures and implant locations. An external fixator helps position the pins properly to align the bones. External fixation often inadequately reduces humeral shaft fractures, though it can immobilize the bone segments before a more definitive reduction procedure is performed.

Intramedullary nail fixation involves placing a metal rod inside the humeral canal proximodistally (antegrade) or distoproximally (retrograde). Theoretically, this technique can accelerate recovery and help avoid radial never palsy. However, recent studies show that there is no difference in nonunion rates or radial nerve palsy between ORIF and intramedullary nailing.[11][12] The antegrade approach requires rotator cuff disruption and subsequent repair, which risks rotator cuff injury. Meanwhile, the radial nerve is vulnerable to injury with the retrograde technique. Musculocutaneous nerve injury can occur when locking screws in the anterior-posterior plane. Severe shoulder pain can result from intramedullary nailing.

ORIF entails incision over the fracture site, reducing the bone, and attaching internal fixators such as plates and screws on the bone fragments. ORIF allows better alignment of simple fractures and quicker initiation of secondary healing in comminuted fractures. The incision's location is decided based on fracture location and pattern and the surgeon's preference.

The anterior humeral approach is commonly used for proximal- and middle-third fractures. An incision is made between the deltoid, pectoralis major, and pectoralis minor to avoid the axillary and medial and lateral pectoral reves. The cephalic vein and its surrounding fat stripe lie in this region and serve as landmarks. The brachialis is situated deep in the area and can be safely incised to access the humerus because of its dual innervation.

The anterolateral approach uses the same superficial dissection. However, rather than splitting the brachialis, the muscle is separated from the brachioradialis, exposing the radial nerve during surgery. This approach risks damaging the radial and axillary nerves and the anterior circumflex humeral artery.

The posterior approach is best for distal humeral shaft fractures. The incision exposes the triceps, which can be split or retracted to access the humerus. The radial nerve exits the posterior arm compartment about 10 cm proximal to the radiocapitellar joint.

Internal fixation can start after reducing the humeral shaft fracture. Simple fractures are amenable to lag-screw fixation and subsequent compression plating, typically with a 4.5-mm lateral compression plate. A 3.5-mm plate may also be used, though this may alter patients' weight-bearing protocol after surgery. The lag screw is typically placed perpendicular to the fracture site. Meanwhile, comminuted fractures are best fixated with a bridge plate.

Simple fractures typically heal by primary bone healing, while comminuted fractures heal by secondary healing. In primary or direct healing, the bone fragments are perfectly aligned. The bone fragments reconnect and heal by direct remodeling of the lamellar bone and Haversian canals.

In contrast, secondary or indirect bone healing occurs in stages: hematoma formation, granulation tissue formation, bony callus formation, and bone remodeling (see Image. Comminuted Humeral Shaft Fracture). Hematoma formation sets off inflammation and angiogenesis. Granulation tissue formation is critical to bridging the bone fragments. In callus formation, the callus starts as a cartilaginous structure that later undergoes endochondral ossification to become a hard callus. Remodeling further strengthens the hard callus.[23]

Sarmiento et al advocated for nonoperative humeral shaft fracture treatment, believing it is highly successful. However, recent studies show that conservative management leads to nonunion more frequently than originally thought. [13][14] Furthermore, humeral shaft fracture surgery promotes early recovery more than conservative treatments, which is especially important for patients with multiple injuries.[15]

Differential Diagnosis

Humeral shaft fractures may be classified based on anatomic location and severity. Fractures involving different humeral locations—proximal, middle, or distal third—present with different associated injuries. Accurate localization is vital to proper management.

Other conditions presenting with arm pain include shoulder and elbow dislocation, tendon and muscle tears, neuropathies, and soft tissue inflammation from causes like infection and contusion. However, these conditions involve different locations and etiologies and are accompanied by other symptoms.

Staging

The Orthopedic Trauma Association (OTA) uses an alphanumeric classification scheme for fractures. The humerus bone is designated the number 1. A humeral fracture is designated 1 if proximal, 2 if midshaft, and 3 if distal. A fracture pattern is designated A if simple, B if wedge, and C if complex. Thus, a midshaft humeral wedge fracture is classified as 1.2-B.

However, the OTA classification is not commonly used when writing a complete humeral shaft fracture diagnosis. Rather, the fracture is more often described in terms of location and type during diagnosis, eg, "Fracture, Humerus, Proximal Third, Spiral."[16].

Prognosis

Most humeral shaft fractures have a good prognosis. Conservatively treated closed fractures have a nonunion rate ranging from 3% to 17.6%. Meanwhile, humeral shaft fractures treated surgically have high union rates, though they are also associated with high surgical costs and postoperative soft-tissue complication rates. Immobilization can last up to 10 weeks after injury. Physical therapy can help patients regain full strength and mobility.[17]

Complications

Humeral shaft fractures can cause complications related and unrelated to treatment. Those related to nonoperative treatment include skin irritation to cast and splint materials and progressive fracture displacement. Meanwhile, surgical fixation can cause infection, non-healing of the surgical site, hardware failure, and prominent hardware. Intramedullary nailing often produces severe pain.

Nonunion and radial nerve palsy are not always treatment-related. Nonunion is defined as having no evidence of healing 6-12 months after injury. Delayed union is defined as healing of a fracture 4-6 months after injury.[18] Lack of callus formation and persistent motion at the fracture site 6 weeks after injury have nearly 100% positive predictive value of nonunion.

Nonunion can arise by different mechanisms. Atrophic nonunion occurs when the bone does not heal due to the failure of the bone-healing processes or the body's inherent lack of ability to repair bones. Common causes include infection, vitamin deficiency, arterial disease, immunosuppression, and connective tissue disease. A diagnostic workup and reevaluation of the patient's history are necessary to determine the source of the problem and the appropriate corrective measures. The patient must be counseled about the importance of smoking cessation and blood glucose control.[19]

On the other hand, hypertrophic nonunion is typically due to fracture site instability. Radiographs will show excessive bony callus formation without bridging at the fracture site. Hypertrophic union requires surgery to minimize fracture site motion and promote healing.

Radial nerve palsy is an associated injury in approximately 11.8% of humeral shaft fractures, especially spiral fractures of the humerus' distal third. Surgery is not always indicated for this condition because 70-90% of radial nerve palsies spontaneously recover 2-3 months after injury. However, it must be corrected if immediate surgery is performed for more emergent conditions, such as vascular compromise.[20] A cock-up wrist brace may be used to counter wrist drop and prevent contractures. Functional recovery of this nerve is observed first in the brachioradialis, which extends and radially deviates the wrist. The last to regain function is the extensor indices.

A nerve conduction study or electromyography (EMG) must be ordered for patients who show no signs of improvement after 2-3 months. Open surgical exploration is indicated when fibrillations are present on EMG or if the patient still fails to improve after 4-6 months. If radial nerve function does not improve afterward, tendon transfer may be performed to restore as much wrist-and-finger extensor function as possible.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients typically undergo a period of immobilization immediately after injury or surgery. A step-wise progression in mobility and weight-bearing capacity is expected over the next 6 weeks to 3 months. Initially, patients perform assisted range-of-motion exercises of the elbow and shoulder using their contralateral arm or with the aid of a physical therapist. With improvement, they can start working on passive and active range of motion and weight-bearing.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educating patients about humeral shaft fractures helps them understand their treatment options and what to expect during rehabilitation. Notably, the nature of the injury must be explained in simple terms. Include details about the physical examination and imaging test results. Then, discuss the available treatment options, but emphasize that therapeutic plans are individualized. Help the patient understand if conservative or surgical management is better in their case. The benefits and risks of each treatment must be thoroughly explained.

After deciding on the therapeutic approach, talk to the patient about what they can expect during the treatment process. For example, patients on conservative treatment must be given clear instructions about pain control, ice application, arm elevation, and intake of other medications at home. Explain the signs and symptoms warranting immediate medical attention. Provide the patient with a schedule of their follow-up days and required diagnostic tests. Individuals undergoing surgery must be informed about their schedule and things they should do to prepare.

Explaining the risk factors for sustaining humeral shaft fractures may enlighten patients and prevent recurrences. Identify the medical conditions or risky behaviors that make patients vulnerable to this kind of injury. Include recommendations for lifestyle modifications when counseling patients.

As for recovery, the patient must be informed about the expected healing time and activities to avoid. Emphasize the importance of physical therapy. Emotionally traumatized patients must be given support and reassurance, though a referral for counseling and psychological therapy must also be considered.

Patient education should be tailored to individual needs. Encourage patients to actively participate in the healthcare decision-making process to empower them during recovery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The interprofessional team managing humeral shaft fractures must include an orthopedic surgeon, emergency department physician, nurse practitioner, radiologist, and therapist. Most of these fractures are managed nonsurgically, so a thorough knowledge of the outpatient follow-up protocol and smooth healthcare team coordination ensure good patient outcomes.

Serial X-rays must be obtained to monitor bone healing. Physical therapy must be started once the cast is removed to restore muscle strength and range of motion. The pharmacist should educate the patient on pain management. Patients must be referred to an orthopedic specialist if nonunion occurs or other complications develop.