Introduction

Gabrielle Falloppio first discovered the inguinal ligament (or Poupart ligament) in 1562, which was further described by Francois Poupart, the famous French anatomist.[1] The ‘tendinous’ anatomy of the inguinal ligament, stretching from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the pubic tubercle (PT) with its grooved superior surface, was later discussed in detail by Cunningham. It forms by the folding of the inferior extent of the external oblique aponeurosis. The importance of the inguinal ligament in surgery stems from the fact that it is an important landmark and integral component of groin hernia repair and inguinal disruption (sportsman groin). Among the most commonly performed surgeries in the world is inguinal hernia repair, done on more than 20 million people per annum. The lifetime occurrence of groin hernia which includes visceral or adipose tissue protrusions through the inguinal or femoral canal is 27 to 43% in men and 3 to 6% in women.[2][3] Inguinal hernias are almost always symptomatic, and surgery being the only cure. Acquiring detailed knowledge of inguinal anatomy is essential for surgeons operating on groin hernias.

Structure and Function

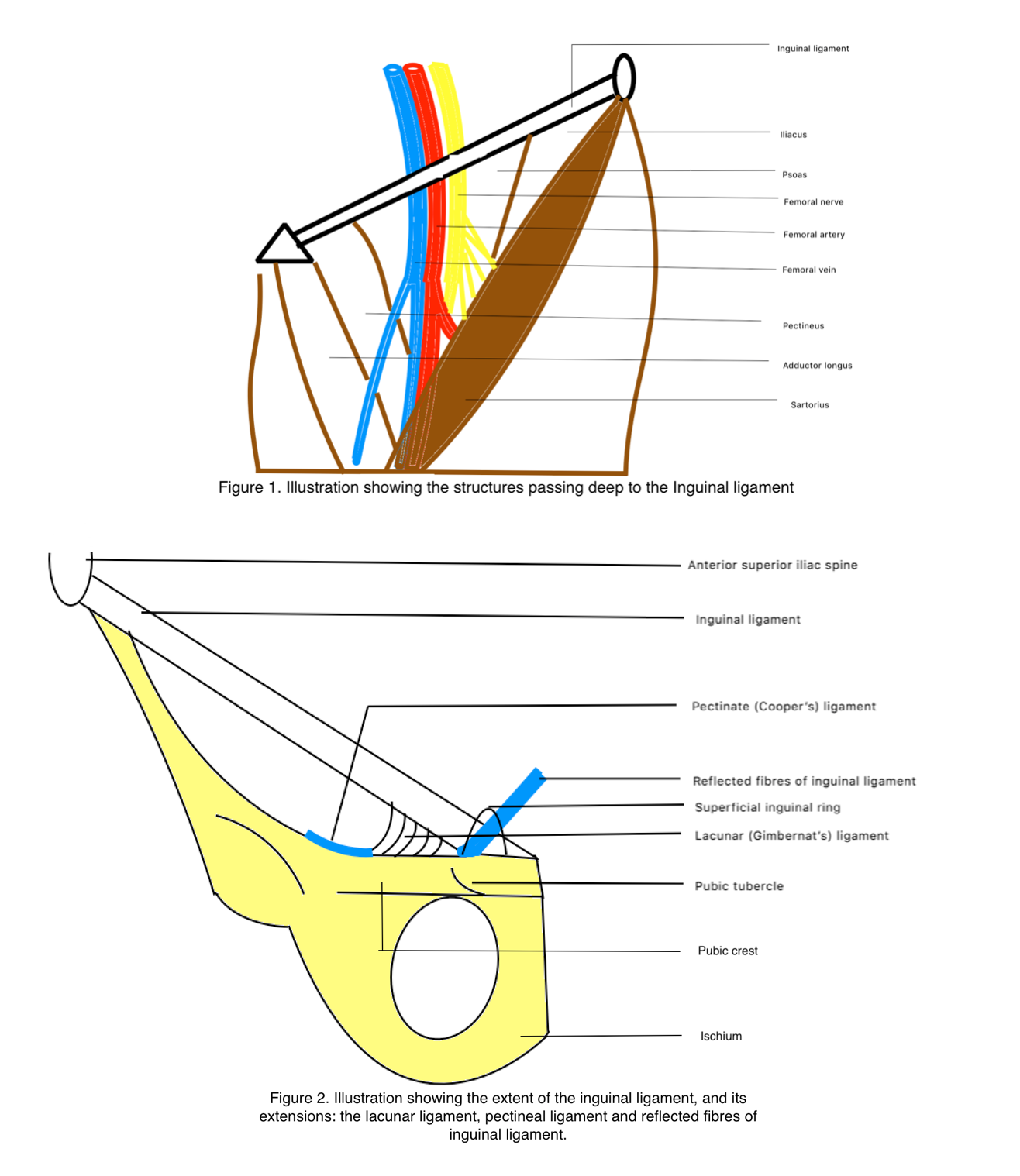

The most superficial of the anterior abdominal wall musculature is the external oblique muscle, which arises from the posterior aspect of the lower eight ribs. The muscle fibers are directed almost horizontally in its upper portion to oblique in the middle and lower portions where they continue as an aponeurosis. The fibers fan out and are inserted from above to below into the xiphoid process, linea alba, pubic crest, pubic tubercle, and anterior half of the iliac crest. The obliquely arranged anteroinferior fibers of the aponeurosis fold on themselves inwards to form the inguinal ligament, running between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The inguinal ligament is connected below to the fascia lata of the thigh, which results in its caudally directed convexity. The ligament bridges the neurovascular and muscular structures that pass from the deep pelvis to the thigh.[4] The structures that lie deep to the inguinal ligament from lateral to medial are[5]: (Figure 1)

- The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

- Femoral nerve

- External iliac artery to femoral artery

- Femoral vein to external iliac vein

- Femoral ring with deep inguinal lymphatic channels and lymph nodes

- The muscles from lateral to medial include iliacus, psoas, pectineus, and adductor longus

The mid-inguinal point is an important surgical landmark, which forms the midpoint of the imaginary line that joins the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. Deep to this point, the external iliac artery continues as the femoral artery, passing from the pelvic cavity to the lower limb. Palpation of the femoral artery is only possible below the inguinal ligament at the mid-inguinal point. The midpoint of the inguinal ligament (the midpoint between the ASIS and the pubic tubercle) is just lateral to the mid-inguinal point. It is an important surgical landmark of the deep inguinal ring, that lies 0.5 inches above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament.[6] The inguinal ligament is rounded and oblique laterally, whereas medially it is grooved and becomes more horizontal. The superior surface of the inguinal ligament is grooved and forms the floor of the inguinal canal and contains the ilioinguinal nerve and the spermatic cord in males and round ligament in females.

Attachments of the Inguinal Ligament

The inguinal ligament attaches below to the fascia lata which is the deep fascia of the thigh. Superiorly it gives origin to the internal oblique from lateral two thirds, transverses abdomens from lateral one thirds, and cremaster muscle from the middle third.

Extensions

At the medial end, the inguinal ligament fans out when attaching to the pubic tubercle which is called the lacunar ligament or Gimbernat ligament. The apex of the lacunar ligament is at the pubic tubercle, anteriorly attached to the inguinal ligament and posteriorly attached to the pectinate line, while the base lies laterally. The pectinate ligament (ligament of Cooper) is a lateral extension from the base of the lacunar ligament that is attached to the pecten pubis.

Few reflected fibers of the inguinal ligament travel superomedially at an angle of 45 degrees initiating at the lateral crus of the superficial inguinal ring and decussates with fibers of the opposite side at the lines alba just anterior to the pyramidal muscle (if present), and if not present, is attached to the rectus sheath. Reflected fibers of the inguinal ligament are also called the Colle ligament, triangular fascia or reflex ligament. In a study from 2009, 83% of cadavers had a reflected inguinal ligament.[7]

Inguinal Ligament: A ligament or Tendon?

The argument of the taxonomy of the inguinal ligament of being either a tendon versus ligament continues, as they both broadly include a similar type of connective tissue composition. Grossly, ligaments and tendons get classified according to their connections; either bone to bone for ligaments or skeletal muscle to the bone for tendons. However, the inguinal ligament that arises from the aponeurosis of the external oblique aponeurosis and connects the ASIS to the pubic tubercle does not fall neatly into either of the above basic definitions. Another consideration is that the function of a musculoskeletal ligament is to stabilize a joint between two bones. Although separate in children, mature adults have ileum and pubic bones fused into a single pelvic bone. Therefore, there is no joint to be stabilized by the inguinal ligament. According to previous literature, ligaments provide stability to joints and hence must always be preserved during surgery, and never to be divided intra-operatively. Since tenotomy of the inguinal ligament is continued to be performed by surgeons for patients with inguinal disruption, it poses questions over the anatomical classification of the inguinal ligament.[1]

Embryology

In all vertebrates, somitic dermatomyotomes give rise to the musculature of the body. The myocytes of the ventral body wall develop from the lateral or hypaxial half of the dermomyotome, and ventral branches of spinal nerves innervate them. The hypaxial muscle differentiates into three separate layers, which becomes apparent by the end of the sixth week of embryonal development. These muscles, depending on their position in the following stages, correspond to external oblique (outer layer), internal oblique (middle layer) and transverse abdominal muscles (inner layer).[8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The external iliac artery that exits the pelvis immediately deep to the inguinal ligament, and continues as the femoral artery which runs through the femoral triangle (bound by the inguinal ligament, the sartorius, and the abductor longus muscle), parallel to the femoral vein and the deep inguinal lymphatics through the femoral canal.[9]

Nerves

Two nerves pass immediately deep to the inguinal ligament. They are:

The lateral cutaneous femoral nerve of the thigh usually arises from the posterior division of the L2 and L3 spinal nerves. It courses from the lumbar spinal roots through the pelvis, in a direction towards the ASIS. At this point, it leaves the pelvis by traveling beneath the inguinal ligament, anterior to the ASIS, and in the thigh it divides into two branches, viz the anterior and posterior divisions, providing sensory innervation for the skin of the anterolateral and lateral aspects of the thigh.[10]

The femoral nerve arises from the posterior divisions of ventral rami of L2, L3, and L4, passes through the pelvis, deep to the inguinal ligament, just lateral to the femoral artery and enters the femoral triangle where it supplies muscles and cutaneous innervation of the thigh.

Surgical Considerations

The inguinal ligament and the lacunar ligament form the anterior and medial wall of the femoral ring respectively, which if weakened can lead to herniation of abdominal contents through a narrow neck leading to a femoral hernia.[6] A Laugier hernia is the protrusion of abdominal contents through a weakness in the lacunar ligament.

A groin injury, sportsman groin, and inguinal disruption are synonyms for diffuse chronic groin pain syndrome, which affects athletes performing high-intensity exercise, which is usually unresponsive to conservative therapy.[11] One of the etiologies of inguinal disruption is inguinal ligament dehiscence. Hence, the inguinal ligament is a target for use as a tendon for therapeutic strategies in the management of inguinal disruption among athletic groups.

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of the inguinal ligament cannot be understated, as it an important landmark for diagnosis and while performing inguinal surgery. The inguinal ligament serves to help differentiate the type of groin hernia clinically. If the hernia bulge occurs above the inguinal ligament, it is considered to be an inguinal hernia, and when the bulge occurs below the inguinal ligament, it is a femoral hernia. Any inguinal hernia arising within the Hesselbach triangle (triangle bound by the lateral border of rectus sheath medially, inguinal ligament below and inferior epigastric artery laterally) is a direct inguinal hernia, whereas if it arises lateral to the triangle through the deep inguinal ring, it is an indirect inguinal hernia.