Continuing Education Activity

Herpes simplex virus can cause infection in the eye. Recurrent infection of the cornea due to this virus causes herpes simplex keratitis. It can easily progress to corneal perforation or blindness if left unchecked. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of 'herpes simplex keratitis' and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of herpes simplex keratitis.

- Outline the typical presentation of a patient with herpes simplex keratitis.

- Identify the most common complications of herpes simplex keratitis.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients with herpes simplex keratitis.

Introduction

Herpes simplex keratitis is caused by recurrent infection of the cornea by herpes simplex virus (HSV). The virus is most commonly transmitted by droplet transmission, or less frequently by direct inoculation. Herpes keratitis remains the leading infectious cause of corneal ulcers and blindness worldwide.

Etiology

HSV is enveloped and has a linear double-stranded DNA genome. It has two subtypes: HSV-1 and HSV-2, each affecting different regions of the body. The following etiological factors are responsible for the spread of the disease:

Primary infection:

- HSV-1: HSV-1 causes infection in the face, lips, and eyes. The involvement of the cornea is due to direct infection.

- HSV-2: HSV-2 infects the genitalia; however, it may get transmitted to the eye through infected secretions, either venereally or at birth (neonatal conjunctivitis).

- Environmental conditions: HSV transmission facilitation occurs in conditions of crowding and poor hygiene.

Reactivation:

Primary infection may become latent, which may be reactivated later in life due to a variety of stressors such as fever, trauma, immunosuppression, hormonal change and radiation exposure, etc.

Epidemiology

Herpetic eye disease is the most prevalent infectious cause of corneal blindness in developed countries. Seroprevalence of HSV-1 is over 50% in the US while more than 75% in Germany.[1][2] Approximately 10 million people worldwide may have herpetic eye disease. The global incidence (rate of new disease) of herpes keratitis is about 1.5 million, including 40000 new cases of severe monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.

Primary infection:

Primary infection may occur at any point in life. Studies showed the mean age for the first occurrence of ocular HSV-1 infection to be 37.4 years in the US,[3] and 25 years in Britain.[4]

Recurrence:

Dendritic keratitis showed the most frequent recurrences (56.3%), followed by stromal keratitis (29.5%), and geographical lesions (9.8%).[5] The greater the number of previous attacks, the greater the risk of recurrence. It also depends upon various external insults, e.g., fever, trauma, etc.

Pathophysiology

Corneal epithelial cells express specific receptors (Nectin 1, HVEM and PILR-alpha, etc.) that facilitate viral entry into the cells.[6] Primary infection with the virus is commonly subclinical, and the only manifestation may be mild, self-limiting blepharoconjunctivitis. The cornea is rarely involved in primary infection. During this phase, however, the virus is carried to the sensory ganglion for that dermatome (e.g., trigeminal ganglion) and becomes latent. Recurrent infection occurs when this latent virus becomes reactivated (due to a variety of stressors such as fever, trauma, immunosuppression, etc.) in the ophthalmic branch of trigeminal ganglion and subsequently results in shedding at the corneal surface.[7] Recurrence may be limited to the epithelium with the virus replicating in and destroying epithelial cells (dendritic/geographical keratitis).[8] Or it may go on to involve the deeper endothelial layer (disciform/stromal keratitis).[9] Another theory for the development of the endothelial disease is that it is essentially an autoimmune response. Studies showed that HSV-1 protein represented an antigenic mimic that triggered an immune reaction against the corneal antigens.[10]

History and Physical

History:

The patient may give a history of previous episodes, corneal abrasion due to contact lens wear, or oral or nasal sores. They might be taking topical or systemic steroids. The patient might have a history of immune deficiency state, or even recent fever or sun/UV exposure.

Presenting symptoms:

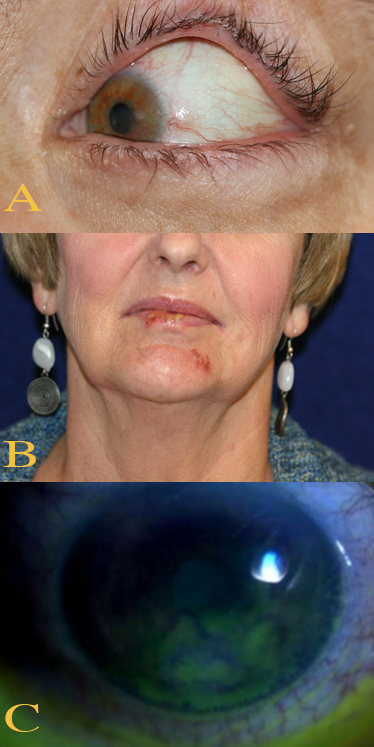

It is commonly subclinical, and the only manifestation may be mild, self-limiting blepharoconjunctivitis, marked by inflammatory vesicles or ulcers and can include lesions in the corneal epithelium.[11] Mild fever, malaise, or upper respiratory tract infection may also be present.

Dendritic/Geographical keratitis presents with pain, foreign-body sensation, light sensitivity, redness, and blurred vision.[12] Corneal sensations eventually get reduced. Patients with Disciform keratitis may experience similar symptoms. However, discomfort and redness tend to be milder than epithelial disease. They also complain of haloes around lights.

Signs:

Any or all of the following may characterize infection:

- Corneal epithelial disease (dendritic/geographical keratitis):

Signs in chronological order[13][14]:

- Swollen opaque epithelial cells arranged in a coarse punctate or stellate pattern

- Central desquamation results in linear branching (dendritic) ulcer

- The central part forms the ulcer bed while the ends of the ulcer have characteristic terminal buds. These are visible with special stains (fluorescein and rose bengal stains)

- The ulcer may progressively increase in size to give a 'geographical' or 'amoeboid' configuration

- Mild subepithelial scarring may develop after healing.

- Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP)

- Corneal stromal disease (disciform keratitis)[15]:

- Occasionally eccentric lesion

- Central zone of stromal edema with overlying epithelial edema

- Keratic precipitates underlying the edema

- Folds in the Descemet membrane in severe cases.

- Subepithelial and/or stromal scarring may develop after healing

- Wessely immune ring

- Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP)

A nonhealing epithelial defect, sometimes after prolonged topical treatment. May be associated with stromal melting and perforation.

Vesicles on eyelids/skin, conjunctivitis, uveitis and/or retinitis.

Evaluation

Workup of HSV keratitis proceeds in the following manner:

- History: It is the first step to pinpoint the etiology of the disease.

- External examination: Distribution of skin vesicles may help distinguish HSV (vesicles concentrated around the eye) from HZV (vesicles extended to the forehead, scalp, and tip of the nose) keratitis.

- Slit-lamp examination: This is the most important step since it helps identify the characteristic signs of herpes keratitis. The ulcer bed is visualized better with fluorescein dye while the virus-laden cells at the margins with rose bengal dye.[16][17] IOP measurement is also carried out in this step.

- Check corneal sensation: This may decrease in herpes keratitis. Do this before instilling topical anesthetic.

- Laboratory tests: Herpes simplex is usually diagnosed clinically and requires no laboratory confirmation. If the diagnosis is in doubt, any of the following tests are options:

- Scrapings of a corneal or a skin lesions for Giemsa stain or Tzanck smear - ELISA testing is also available

- Viral culture

- HSV antibody titers. They rise after primary but not recurrent infection

Treatment / Management

Treatment depends upon the type of disease from which the patient is suffering.

- Epithelial keratitis[18][19][18]:

- Topical: Acyclovir 3% ointment and ganciclovir 0.15% gel, each administered five times daily. Trifluridine can also be used up to nine times a day. 99% of cases resolve by two weeks on this treatment.

- Debridement: The corneal surface is anesthetized, and then wiped with a sterile cellulose sponge 2 mm beyond the edge of the ulcer to achieve virus-free margins. This technique can be employed for dendritic but not geographical ulcers.

- Oral antivirals: Immunodeficient patients or patients who respond poorly to topical therapy benefit from this method.

- Skin lesions: Acyclovir cream five times daily may be used, as for cold sores.

- Interferon monotherapy: A combination of nucleoside antiviral with interferon speeds up healing.

- IOP control: Prostaglandin derivatives should be avoided as they promote viral activity and inflammation in general.

- Topical steroids: These are avoided unless significant disciform keratitis is also present.

- Disciform keratitis:

- Starting treatment: Initially, topical steroids with antiviral cover, both used four times daily. The frequency of both is reduced in parallel over the next 4 weeks as improvement occurs.

- Subsequently: Prednisolone 0.5% (or other weaker steroids) once daily is considered a safe dose. Antivirals should be stopped altogether at this point. Periodic attempts should be made to stop steroid treatment as well.

- Active epithelial ulceration: Steroid treatment should be reduced to a minimum when an epithelial disease is also present. The antiviral cover should be made more aggressive.

- Topical ciclosporin: This may be useful, particularly in the presence of epithelial disease.

It is the same as that of persistent epithelial defects. The use of steroids should remain at a bare minimum.

The treatment is broadly similar to that of disciform keratitis, but much aggressive antiviral therapy may be beneficial.

Keratoplasty is the last resort when the disease causes irreversible corneal damage. However, recurrence of the disease of rejection threatens the survival of grafts.

Prophylaxis should merits consideration in patients with frequent recurrences or those with bilateral disease. Acyclovir 400 mg twice daily is standard, but if necessary, a higher dose is an option. Oral valaciclovir or famciclovir are alternatives to acyclovir. Prophylaxis reduces the rate of recurrence by about 50%.

Differential Diagnosis

- HZV keratitis

- Recurrent corneal erosion

- Acanthamoeba keratitis

- Vaccinia keratitis

- Epithelial rejection in a corneal graft

- Tyrosinaemia type 2

Prognosis

The prognosis of HSV keratitis is generally favorable with therapy. The majority of dendritic ulcers heal spontaneously without treatment. Mild to moderate disease recovers with just 2 weeks of topical therapy reinforced with debridement if needed. However, prolonged epithelial or disciform keratitis may lead to scarring and vascularization, and visual acuity may be lost.

Complications

- Secondary infections may occur.

- Glaucoma secondary to either inflammation or chronic steroid use is common.

- Cataract, the occurrence of which may be due to inflammation or chronic steroid use.

- Iris atrophy secondary to kerato-uveitis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should focus on the avoidance of overcrowding and poor hygiene. Hand-eye contact should be avoided as much as possible, particularly scratching the eye with dirty hands. Regular handwashing should be encouraged. Infected individuals should keep themselves isolated from close family and friends to avoid spread. Once the patient has the diagnosis, they need to understand its nature and mode of propagation along with necessary preventive measures. They should also receive adequate counsel about possible complications due to inadequate treatment compliance.

Pearls and Other Issues

The physician should always consider herpetic corneal disease in any patient presenting with keratitis. Often, the dendritic lesion may show some days after the initial conjunctivokeratitis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Herpes keratitis is a very common infection that is often first seen by the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, or the emergency department physician. These clinicians should always consult with the ophthalmologist before starting any treatment. The disease needs to be dealt with in time to avoid morbidity. Coordination among healthcare professionals is vital for better patient outcome. Ophthalmologists, opticians, dermatologists, nurses, and pharmacists all need to work in coherence to tackle the disease and all the possible complications. Even after treatment, the patient should be closely followed until the symptoms have subsided, and the visual acuity is normal. Surgeons also need to be onboard since surgery may be the only last resort. Interprofessional communication is the key to manage the problem at its core appropriately.

An interprofessional healthcare team approach is necessary. The physicians will decide the course of treatment and prescribe appropriate therapy. Nursing can assist in patient education about the disease, as well as assess therapeutic effectiveness and patient compliance. Pharmacists should verify dosing and perform medication reconciliation to ensure the absence of drug-drug interactions. Any concerns form nursing or pharmacy should be reported to the treating physicians promptly. Herpes keratitis management will be optimized by this type of interprofessional, collaborative approach, leading to better patient outcomes. [Level 5]