Continuing Education Activity

The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the two cruciate ligaments that aids in stabilizing the knee joint. It is the most commonly injured ligament in the knee, commonly occurring in football, soccer, and basketball players. Treatment consists of the “RICE” therapy, which includes rest, ice, compression of the affected knee, and elevation of the affected lower extremity. This activity describes the evaluation and management strategies for such injuries and stresses the role of team-based interprofessional care for patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries.

Objectives:

Describe the clinical features of anterior cruciate ligament injuries.

Outline the detailed evaluation in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries.

Explain the management and long-term rehabilitation of patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries.

Review the need for improved care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to enhance care delivery and prevent long-term disability in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries.

Introduction

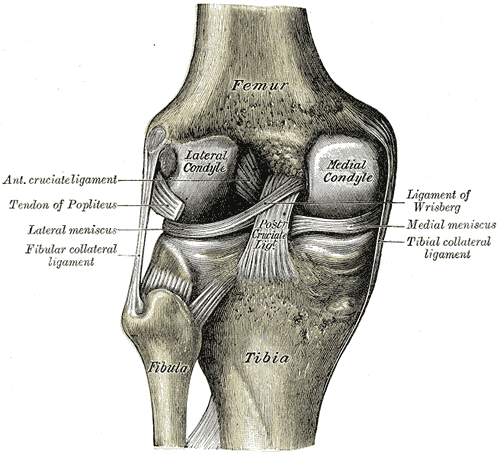

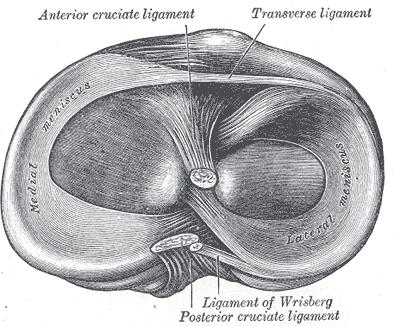

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of 2 cruciate ligaments that aids in stabilizing the knee joint. It is a strong band made of connective tissue and collagenous fibers that originate from the anteromedial aspect of the intercondylar region of the tibial plateau and extends posterolaterally to attach to the medial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle, where there are two important landmarks; The lateral intercondylar ridge which defines the anterior boundary of the ACL, and the bifurcate ridge which separates the 2 ACL bundles. The ACL measures 32 mm long and is 7 to 12 mm wide. It has two bundles; an isometric anteromedial and a posterolateral bundle with more versatile length changes.[1]

The anteromedial bundle is the tightest in flexion and is mainly responsible for anterior tibial translation (85% of the stability), whereas the posterolateral bundle is the tightest in extension, with the main role in providing medial-lateral and rotational stability (secondary restraint).[2][3][4]

The ACL has 2200 N strength. The ACL and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) together form a cross (or an “x”) within the knee and prevent excessive forward or backward motion of the tibia relative to the femur during flexion and extension. Histologically, the ACL is composed of type I collagen (90%) and type III collagen (10%). It receives blood supply predominantly from the middle geniculate artery. Neurological innervation from the posterior articular nerve is a branch of the tibial nerve.[5]

Etiology

Most ACL tears occur in athletes by non-contact mechanisms, non-contact pivoting injury where the tibia translates anteriorly while the knee is slightly flexed and in valgus.[6] A direct hit to the lateral knee has also been encountered as an injury mechanism. The most at-risk athletes for non-contact injury include skiers, soccer players, and basketball players.[7] The most at-risk athletes for contact injury are football players.[8]

Multiple intra-articular and extra-articular injuries can be associated with acute ACL ruptures.[9][10][11][12] Among those are meniscal tears; lateral meniscus injury in over half of acute ACL tears, whereas the medial meniscus is more involved in chronic cases. The PCL, LCL, and PLC could also be injured in association with an ACL injury. Chronic ACL deficiency seems to have deleterious effects on the knee, with the development of chondral injuries and complex unrepairable meniscal tears. Such as bucket handle medial meniscus tears.

Epidemiology

The ACL is the most commonly injured ligament in the knee, almost half of all knee injuries. The annual reported incidence in the United States alone is approximately 1 in 3500 people. There are approximately 400,000 ACL reconstructions every year in the united states.[13] However, data may not be accurate as there is no standard surveillance.

There is no age or gender bias; however, it has been suggested that women are at an increased risk of ACL injury secondary to a multitude of factors.[14] In athletes, the female-to-male ratio has been reported to be 4.5: 1. Female athletes tend to get ACL ruptures at a younger age and more in the supporting leg versus the kicking leg in males.

Among the factors increasing the female risk, as suggested by some studies that females may have weaker hamstrings (more quadriceps dominant) and preferential recruitment of the quadriceps muscle group while decelerating. Engaging the quadriceps musculature while slowing down places abnormally increased stresses on the ACL, as the quadriceps muscles are less effective at preventing anterior tibial translation versus the hamstring muscles. Additionally, females have weaker core stability than males.

Landing biomechanics in females may increase the risk of ACL injury with increased valgus angulation and extension of the knee.[15][16] One study utilizing video analysis demonstrated that female athletes are more likely to place their knees in increased valgus angulations when changing directions suddenly, which increases the stress on the ACL ligament, in addition to decreased hip and knee flexion and decreased fatigue resistance.

Other risk factors that might increase the risk of injury include anatomical risk factors such as increased body mass index, smaller femoral notch, impingement on the notch, smaller ACL, hypermobility, joint laxity, and previous ACL injury.

Certain risk factors related to specific sports participation were reported, such as soccer and basketball, with increased risk in females and males, respectively.

Moreover, hormones were reported to affect coordination, especially the preovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle. Females on OCP were noted to be less affected. Estrogen effects on the strength and flexibility of tissues such as ligaments may play a role and predispose females to injury; however, this remains controversial and has yet to be proven.

Collagen production (COL5A1 gene) was noted to be associated with lower injury risk in females.

History and Physical

History: One of the most common knee injuries is an ACL sprain or tear. Typically, injury occurs during activity/sports participation that involves sudden changes in the direction of movement, abrupt stopping or slowing down while running, or jumping and abnormal landing. Verifying the mechanism and time of the injury, ambulatory status, and joint stability can guide the diagnosis.

Most patients would complain of hearing and feeling a sudden "pop" with associated deep knee pain, and about 70% would experience immediate swelling due to haemarthrosis. Other reported symptoms are knee giving way, difficulty ambulating, and reduced knee range of movement.

Physical Examination

Inspection: patients may demonstrate quadriceps avoidance gait (no active knee extension). Varus knee malalignment should be noted as it increases the risk of ACL re-rupture and may warrant a concomitant procedure (knee realignment osteotomy) when performing ACL reconstruction.

Palpation: the involved knee will be swollen (haemarthrosis), and there may be joint line tenderness with an associated meniscal injury.

Movement: the knee may be locked due to associated meniscal injury. Other meniscal and ligamentous structures should be assessed.

Multiple provocative maneuvers can be employed to assess the ACL, including the anterior drawer, pivot shift, and Lachman tests.[17][18]

The Lachman test is the most sensitive in assessing ACL rupture, with 95% sensitivity and 94% specificity. The test is performed with the patient in the supine position and the knee in about 30 degrees of flexion. The clinician should stabilize the distal femur with one hand and, with the other hand, pull the tibia forward. The test is positive when there is increased anterior tibial translation relative to the femur.[19][20]

The test result is interpreted as either a firm endpoint (intact ACL) or no endpoint (ACL rupture). The grade of ACL rupture is classified based on the degree of anterior tibial translation in mm. Grade 1 (3-5 mm), grade 2 (5-10 mm), and grade 3 (> 10 mm translation). However, the injured side should always be compared with the good side. Additionally, the physician should be aware that a PCL tear may result in a "false" Lachman test interpretation due to translating the tibia from a posteriorly subluxated position.

The anterior drawer test is performed with the patient lying supine with their affected knee flexed to 90 degrees and the foot planted (Sometimes, it is easier for the clinician to stabilize the patient's foot by sitting on it). The clinician will grip the proximal tibia with both hands and pull it forward. The test is positive if there is an excessive anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur. It may also be helpful to compare to the unaffected knee as patients may have increased laxity of the ACL that is not pathologic. This test has a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 91% in chronic injuries but not acute injuries.[21]

The pivot shift test mimics the actual giving way event experienced in ACL-deficient knees. The test is performed by internally rotating the tibia while applying valgus stress on the knee and bringing the knee from extension to flexion. The anteriorly subluxated tibia in knee extension will reduce with a clunk in 20-30 degrees of flexion due to iliotibial band (ITB) tension.

The test necessitates intact ITB, MCL, and the absence of knee flexion contracture. This test can be difficult to perform in patients who are guarding, and some may not allow the clinician to perform the test. This is a highly specific test (98%) when positive but is insensitive (24%) due to the difficulty in evaluation secondary to patient pain and cooperation.[21][22]

The lever sign test: is performed by positioning a fulcrum (e.g., examiner's fist) under the proximal part of the supine patient's calf and applying a downward force to the quadriceps (distal thigh). The test is interpreted based on whether the ACL is intact or not; the patient's heel will either rise off of the examination couch or remain down.[23][24]

The KT-1000: This is performed with the knee in slight flexion and 10-30 degrees of external rotation. It helps assess and quantify anterior laxity.

It is important to evaluate for associated injuries such as medial or lateral collateral ligamentous injury, injury to the posterior collateral ligament, or meniscal injuries.[25]

Evaluation

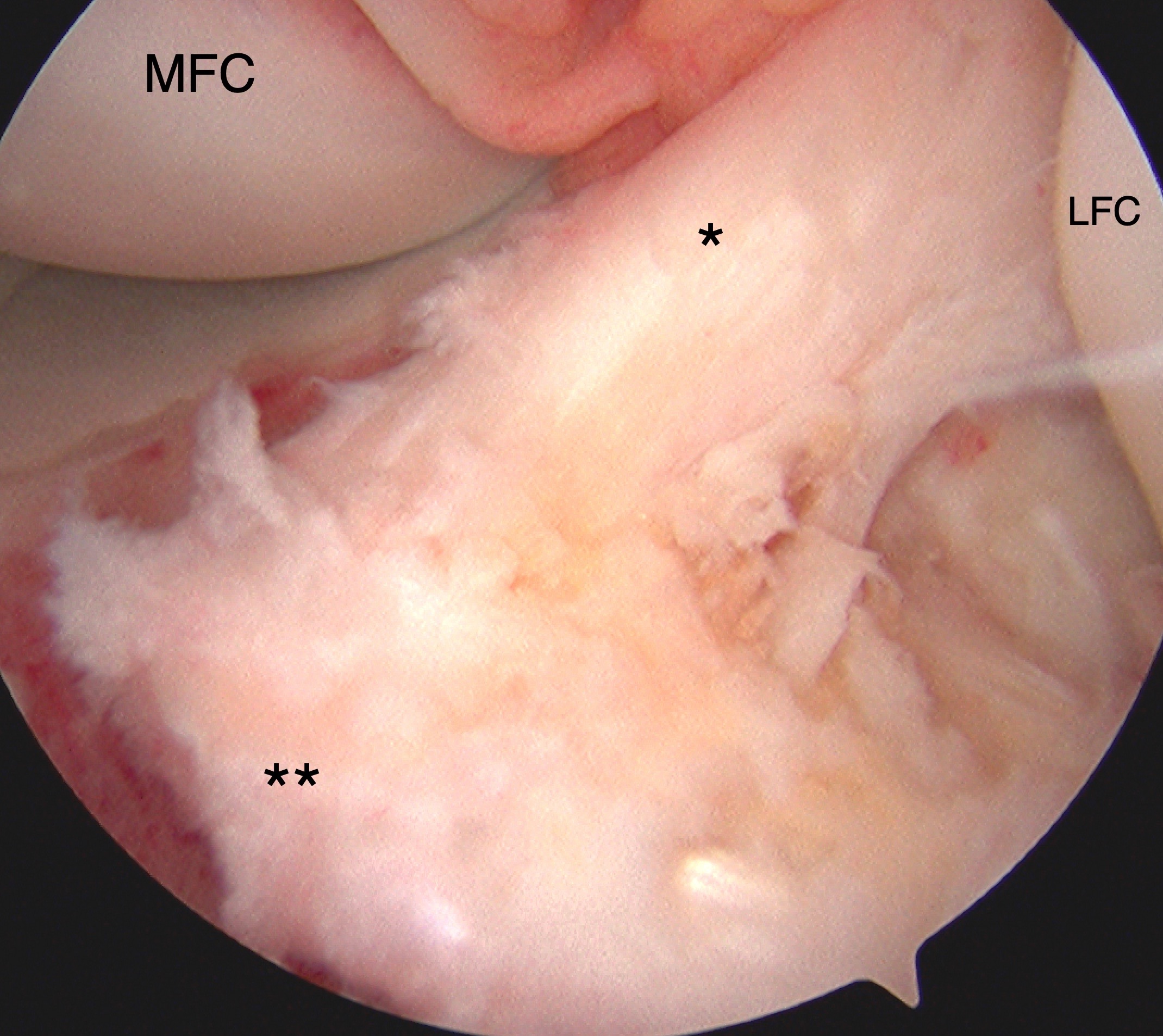

Although ACL injury can be diagnosed clinically, imaging with magnetic resonance (MRI) is often utilized to confirm the diagnosis. MRI is the primary modality to diagnose ACL pathology, with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 95%. Diagnosis may also be made with knee arthroscopy to differentiate complete from partial tears and chronic tears. Arthrography is considered the gold standard as it is 92% to 100% sensitive and 95% to 100% specific; however, it is rarely used as the initial step in diagnosis as it is invasive and requires anesthesia.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is 97% sensitive and 100 % specific: it confirms the diagnosis and assesses the presence of associated injuries. Normal ACL fibers are continuous and steeper than the intercondylar roof. ACL tears have primary and secondary signs.[26][27][28]

Primary Signs

- Sagittal view: will indicate changes associated directly with the ligamentous injury, while secondary signs are those changes closely related to the ACL injury. Primary signs include edema, an increased signal of the anterior cruciate ligament on T2 weighted or proton density images, discontinuity or complete absence of the fibers, and a change in the expected course of the ACL; too flat fibers in comparison with the intercondylar roof or Blumensaat's line. A flat appearance of the ACL fibers is more common in chronic cases where the ACL scars into the PCL. Tears usually occur within the midportion of the ligament, and signal changes are most often seen here and appear hyperintense.

- Coronal View: Empty notch sign where there is fluid against the lateral notch wall. Or discontinuity of the fibers.

Secondary signs include bone marrow edema (secondary to bone contusion) in more than half of ACL tears. The characteristic ACL bone bruising involves the middle third of the Lateral femoral condyle and the posterior third of the lateral tibial plateau. Other secondary signs include Segond fracture (as discussed below), associated medial collateral ligament injury, or anterior tibial translation greater than 7 mm of the tibia relative to the femur (best seen on lateral view), and tibial spine avulsion fracture.

Radiographs: (AP, lateral, skyline or merchant, or sunrise views) are generally non-contributory to diagnosing ACL injuries but help rule out fractures or other associated osseous injuries or may show evidence of effusion. In younger patients, avulsion of the tibial attachment may be seen. Other non-specific features that can be seen on radiographs include:

-

Segond fracture: An avulsion fracture of the anterolateral proximal tibia; attachment site of the lateral capsular ligaments (anterolateral ligament ALL).[29]

-

Arcuate fracture. An avulsion fracture of the proximal fibula; attachment site of the lateral collateral ligament and/or biceps femoris tendon. [30]

- Deep sulcus terminalis sign: This is a depression on the lateral femoral condyle at the junction between the weight-bearing tibial articular surface and patellar articular surface.

-

Joint effusion

-

Deep lateral sulcus sign: A notch on the lateral femoral condyle with a depth of 1.5 mm or more, best seen on the lateral view

Computed tomography (CT) is not generally utilized in evaluating the ACL and is only accurate in detecting an intact ACL. However, it plays a role in evaluating the available bone stock when planning for ACL revision. And it is the most sensitive and specific test for assessing bone loss in cases of tunnel widening and osteolysis.

Treatment / Management

ACL management should have an individualized approach. Both operative and non-operative treatments are acceptable.[31][32][31] Multiple factors should be considered when deciding on ACL management, including the patient's age and demands, activity level, sports participation, and the injury status of other supporting and stabilizing structures.[31]

Acute treatment consists of the "RICE" therapy, which includes rest, ice, compression of the affected knee, and elevation of the affected lower extremity. Patients should be non-weight bearing and may utilize crutches or a wheelchair if necessary. Pain relief can be achieved with over-the-counter medications such as NSAIDs but is typically at the treating physician's discretion.

Non-operative management: this is indicated where there is reduced ACL laxity in low-demand patients or athletes involved in sports with no cutting or pivoting activities. These patients are usually managed with physiotherapy and lifestyle modifications. Non-operative treatment is indicated in partial ACL tears as well.[33] This involves an acute symptomatic treatment followed by 12 weeks of supervised physiotherapy, starting with regaining a full range of motion and progressing to quadriceps, hamstrings, hip abductors, and core muscle strengthening. A serial assessment to evaluate progression should be performed. Functional braces showed no superior functional stability.

However, non-operative management was reported to be associated with an increased risk of meniscal and cartilage damage due to repeated "giving way" episodes, especially if there are level I or II activities such as heavy manual labor and side-to-side sports, jumping, or cutting.

Operative Management

Two main operative management options are repair or reconstruction of the ruptured ACL.[34][35]

ACL reconstruction: this is indicated in a complete ACL rupture in younger active or older active (> 40 years) high-demand patients. The primary objective is an anatomical ACL reconstruction to reinstitute the anterior and rotational stability, consequently lessening the chances of secondary meniscal or chondral injuries. Patients must be rehabilitated to achieve a full range of motion preoperative to reduce the risk of postoperative arthrofibrosis. Also, indicated in the pediatric population, however, activity restriction is unrealistic. A partial ACL rupture with functional instability would indicate reconstruction as well. Returning to sports participation following reconstruction hugely depends upon multiple demographic, functional, and psychological factors.

Surgical technique: arthroscopically assisted; preparation of the graft bed is either by clearance of the native ACL remnants completely or by leaving the stump as guidance for tunnel positioning and augmenting healing; there are no reported differences between these approaches. Also, there are no reported differences in outcomes between single and double-bundle reconstructions. Single bundle reconstruction still is the most common technique. A double-bundle reconstruction might improve native knee kinematics with better stability.

Tunnel Placement

Femur side; transtibial or tibia-independent, either inside-out or outside-in technique. Ideally, tunnel placement in the sagittal plane should be within 1-2 mm of the posterior femoral cortex. In the coronal plane, the aim is to position a more horizontal graft to reduce rotational laxity. So, using the clock face of the lateral wall, the graft should be positioned at 2 o'clock for the left knee or 10 o'clock for the right knee. Anteromedial and far medial drilling portals should be used to facilitate the proper femoral tunnel positioning. Drilling in over 70 degrees of flexion will avoid posterior wall blowout.[36][37]

Tibia side: Sagitally, more than one landmark would guide a final proper tunnel placement. The tunnel's center should be 10 to 11 mm anterior to the anterior border of the PCL, 6 mm anterior to the median eminence, and 9 mm posterior to the anterior inter-meniscal ligament. The tunnel trajectory should be less than 75 degrees from the horizontal in the coronal plane. This can be facilitated by adjusting the tibia starting point halfway between the tibial tubercle and the posterior medial edge of the tibia.[38][39]

Graft placement and fixation: preconditioning of the graft can reduce up to 50% of the stress relaxation. Tensioning at 20 or 40 N has no clinical effects on outcomes. Ideally, the graft should be fixed in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion. Multiple options are available for fixation, which can be used alone or in combination. Aperture or compression fixation can be achieved with an interference screw, whereas suspensory fixation can be achieved by cortical buttons, screws, and washer post or staple fixation.

ACL repair: There has been a resurgence in ACL repair techniques, especially in the pediatric population. Multiple techniques are used, including dynamic intra-ligamentary stabilization (DIS), internal brace ligament augmentation (IBLA), and biological enhancement, such as bridge-enhanced ACL repair (BEAR). The 2-year outcomes show comparable results.

Revision of ACL reconstruction is indicated in failed cases with instability affecting the desired activities. When considering a revision, the underlying etiology of the re-rupture must be identified, along with an assessment of any missed concomitant injuries. Other considerations include previous graft selection and considering stronger grafts, e.g., quadriceps tendon, hamstrings, or allografts. Allografts used for primary reconstruction have two folds higher risk of re-rupture compared to when used in revision cases. Reharversitng bone patellar tendon bone graft is contraindicated.

Combined fixation, aperture, and suspensory fixation should be considered. Also, if there is a previous tunnel dilation of 15 mm or the previous tunnel trajectory would compromise anatomical tunnel creation, bone grafting and staged procedure should be considered. Providing extra stability by anterolateral ligament reconstruction or lateral extra-articular tenodesis is still controversial. Finally, a conservative rehabilitation approach should be followed.

Graft selection for ACL reconstruction is a broad topic with pros and cons for each type of graft.[40][41]

Quadrupled hamstring autograft: This is one of the most common types of grafts used in primary reconstruction. In revision cases, it can be harvested from the contralateral side whenever allograft is not an available or preferred option. Being autologous, so no immune reaction or risk of infection transmission. It can be harvested through a small incision, so less perioperative pain and no anterior knee pain associated with BPTB grafts. It is a strong graft with a maximum load to failure is 4000 N. However, a decreased peak flexion strength at three years was reported compared to BPTB grafts, in addition to reported hamstring weakness in female athletes with consequent increased re-rupture rate.

Complications reported following hamstring harvest include residual hamstring weakness and paresthesia due to saphenous nerve branch injury, where an oblique or horizontal incision can reduce this risk. A "windshield wiper" effect has been described when suspensory fixation away from the joint line would result in tunnel abrasion and dilation with knee range of movement.

Bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autograft is another commonly used graft type. It has the same advantages of being autologous as in the hamstring grafts, in addition to the faster incorporation due to bone-to-bone healing. It is considered the gold standard with a maximum load to failure is 2600 N ( Intact ACL is 1725 N). However, it has the highest incidence of postoperative anterior knee pain, especially with kneeling (10-30%). In addition to the risks of patella fracture and patellar tendon rupture. Higher risk of re-rupture in patients younger than 20 years old and when graft size is less than 8 mm.

Quadriceps tendon autograft: the incision for this graft is advantageous, being away from kneeling pressure areas. In pediatrics, the graft does not involve the physis compared to the BPTB graft. The maximum load to failure is 2185 N. It is either pure soft tissue or involves a patella bone block. Disadvantages are similar to the hamstring tendon autograft with suspensory fixation.

Allografts: are useful in revision settings, in addition to no donor site morbidity. However, they are more expensive, take longer to incorporate, and have a risk of disease transmission ( HIV < 1:1.6 million, hepatitis is greater)—it carries a high risk of graft re-rupture in young athletes, fourfold higher than autografts.

Graft processing: Fresh-frozen grafts have lower re-rupture rates than chemically treated or irradiated grafts. The reason is that the supercritical CO2 decreases the structural and mechanical properties of the grafts. Radiation has effects depending on its dose. More than 3 Mrads kill HIV but at the expense of reduced structural and mechanical properties of the graft. Between 2-2.8, Mrad, and 1 to 1.2, Mrad decreases stiffness by 30% and 20%, respectively—deep freezing and chlorhexidine gluconate (4%) damage cells without affecting the graft's strength.

Timing of ACL reconstruction:

Multiple factors dictate the ideal timing of ACL reconstruction. Additionally, the timing of addressing the associated injuries varies depending on the injured structure.[42][43]

Meniscal tears: this should be addressed concurrently during the ACL reconstruction. Meniscal repair performed in the same setting as ACL reconstruction is reported to have a high healing rate.

Chondral injury: this can also be managed during ACL reconstruction. Staged procedures may be required based on the injury and the management modality. However, the presence of chondral injuries would compromise the long-term patient-reported outcomes following ACL reconstruction.

MCL injury: Grade I and II injuries, which are stable to valgus stress, can be managed non-operatively so that the MCL heals prior to ACL reconstruction. However, in Grade II or III injuries with instability to valgus stress requiring repair or reconstruction, this can be performed in the same stage as the ACL reconstruction. Failure to recognize and manage an associated high-grade MCL injury with valgus instability can compromise ACL reconstruction with high failure rates.[44]

Posterior cruciate ligament injury or posterolateral complex injury: This can be reconstructed concomitantly with ACL reconstruction or as a staged procedure. But, failure to diagnose and manage PCL or PLC injuries will result in varus instability and ACL graft overload.

Realignment osteotomy of the lower limb (high tibial or distal femoral osteotomies): malalignment in either coronal or sagittal planes should be managed before or at the same time as ACL reconstruction. Unmanaged limb malalignment is associated with a high ACL failure rate.

Pediatric consideration for ACL injury and reconstruction:

Non-operative management is indicated in low-demand, compliant children with isolated injuries. Partial ACL tears with no instability on objective testing (Lachman and Pivot shift) are indications for non-operative management. In contrast, a complete ACL tear with objective instability testing indicates operative management. The onset of menarche is the best determinant of skeletal maturity in females. The physis is open to children younger than 14 years old.[45][46][47]

Reconstruction

Intra-articular could be physeal sparing (all intra-epiphyseal), trans-physeal (males ≤13-16, females ≤ 12-14), or partial transphyseal; leaving one physis undisturbed either the distal femur or proximal tibia. There is no reported significant difference in growth disturbances between different techniques.

Combined intra- and extra-articular can be performed in males up to 12 years old and females up to 11 years old. The technique involves harvesting an ITB graft, freeing it up proximally while the distal attachment remains undisturbed. The graft is then looped through the knee in an over-the-top position and passed through the intercondylar notch and inferior to the inter-meniscal ligament anteriorly. Then the graft is sutured to the lateral femoral condyle and proximal tibia.

Adult-type reconstruction should be considered in males from 16 years old and females from 14 years old.

Graft Selection: Soft tissue grafts used in a trans-physeal approach rarely causes growth disturbances.

A high risk of physeal injury has been reported due to multiple factors which can be modified. A large tunnel diameter of more than 12mm is the most significant as it violates more than 7 to 9% of the physeal cross-sectional area, whereas an 8mm tunnel would compromise less than 3% of the physeal cross-sectional area.

Other factors include oblique tunnel trajectory, high-speed tunnel reaming, aperture fixation with an interference screw, dissection close to the perichondral ring of LaCroix, suturing near the tibial tubercle, and lateral extra-articular tenodesis. Overall physeal disruption with no growth disturbance has been reported in 10% of cases.

Differential Diagnosis

- Epiphyseal fracture of femur or tibia

- Medial collateral knee ligament injury

- Posterior cruciate ligament injury

Prognosis

ACL-deficient knees are more prone to the progression of arthritis with further injuries to the chondral and meniscal structures. ACL reconstruction restores native knee kinematics, and a high level of return to sports participation has been reported.

Complications

There are a variety of complications that can happen intraoperative or postoperative.[48][49] Intraoperative such as graft tunnel mismatch, e.g., in BPTB graft, if longer than the combined femoral tunnel, tibial tunnel, and intra-articular portion, will result in prominence of the tibial bone plug and may compromise distal fixation. This can be encountered in BPTB allograft, patella Alta and non-transtibial drilling techniques. However, it is an avoidable situation that is tackled by accurately measuring the tunnel and tailoring the graft accordingly, which can be accomplished by twisting the graft to shorten it.

Tunnel malpositioning: on the femoral side, a vertical tunnel in the coronal plane, instead of a more horizontal one, would result in persistent rotational instability (positive pivot shift test). In the sagittal plane: anterior misplacement yields a tight knee in flexion and loose in extension, and vice versa with posterior misplacement. Clearing the resident ridge would allow a clear view and avoid anterior-posterior misplacement. On the tibial side: too anterior misplacement yields a tight knee in flexion and roof impingement in extension. A posterior misplacement will result in an ACL graft impingement on the PCL.[50]

Another scenario is a posterior wall blowout. This can be overcome by adequate posterior wall exposure and evaluation of the wall after drilling. Also, drilling the tunnel with 70 to 90 degrees of flexion helps avoid this complication. Posterior wall blowout can be managed with redrilling with anteriorly directed trajectory if the defect is minimal and proceed with the same planned fixation. Otherwise, if there is a significant defect, the same tunnel can be used with suspensory fixation and supplementary interference screw.

Graft failure due to various other issues, such as hardware failure, could be due to inadequate fixation, e.g., graft screw divergence > 30 degrees—attritional graft failure due to small graft diameter (< 8 mm). Intra-articular femoral bone plug dislodgement in the BPTB graft would require revision surgery. Missed diagnosis of an associated ligamentous injury or bony malalignment. Improper rehabilitation with too aggressive exercises such as open-chain exercises.

Infection and septic arthritis: This is < 1% of all cases when it occurs and is mostly superficial, with S. epidermidis (coagulase-negative staph) being the most commonly involved pathogen. Routine graft soaking in vancomycin may lower infection risk. Risk factors for infection include graft contamination during intraoperative handling or falling on the floor. Grafts dropped on the floor: this can be managed with multiple soakings in a variety of antibiotic solutions with no increased risk of infection reported.

Patients usually present with the usual infection symptoms and signs such as pain, swelling, erythema, and raised WBC at 2 to 14 days postoperatively. Diagnosis is confirmed with aspiration and gm stain and cultures. Management for intraoperative events, the graft should be soaked in antibiotic solutions before insertion and fixation. Postoperative management involves immediate incision and drainage. The graft can be retained with multiple I &Ds and antibiotics for a minimum of 6 weeks. This philosophy is more likely to work with staph epidermidis but less likely to work with staph aureus.

Stiffness and arthrofibrosis: This is the most common complication following ACL reconstruction, mainly due to a preoperative reduced range of motion. Patients present with reduced patellar movement. Management starts preoperatively with prevention and emphasizes the importance of pre-hab to regain full ROM before surgery—planning surgery after swelling resolution reduces the incidence of arthrofibrosis. Intraoperatively, precision in tunnel positioning is crucial to achieving full ROM, and cryotherapy and aggressive physiotherapy if encountered up to 12 weeks postoperatively. However, if more than 12 weeks postoperatively, lysis of adhesions and manipulation under anesthesia might be indicated.

Infrapatellar contracture syndrome: an uncommon cause of postoperative stiffness with reduced patellar translation.

Patella Tendon Rupture: with evidence of patella Alta on radiographs.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Patella fracture: in BPTB graft and quadriceps tendon graft with bone plug. The majority of the fracture will occur 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively.

Tunnel osteolysis: Unless graft laxity or knee instability exists, tunnel osteolysis should be managed by observation.

Osteoarthritis in the long term: Could be related to associated meniscal injuries. Increased incidence has been reported in patients above 50 years old at the time of ACL reconstruction.[51]

Saphenous nerve irritation has been reported with harvesting hamstring autograft.

Cyclops lesion: This is a fibroproliferative tissue block extension. A click may be heard at the terminal extension.[52]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Immediate postoperative care involves extensive cryotherapy. Patients should be encouraged to fully weight bear as tolerated to reduce patellofemoral pain. The importance of early full passive extension, especially with associated MCL injury or patella dislocation, should be emphasized.

Early rehabilitation should be commenced with exercises that do not exert excessive stress on the graft. At three weeks postoperatively, eccentric strengthening increases quadriceps volume and strength. Other exercises include isometric hamstring contractions at any angle. Isometric quadriceps or simultaneous quadriceps and hamstring contractions. Active knee ROM (35-90 degrees), in addition to core muscles and gluteal strengthening. Closed chain exercises should be emphasized, such as squats or leg-press.

During early rehabilitation: certain exercises should be avoided, such as isokinetic quadriceps strengthening (15-30°), open chain quadriceps strengthening, leg extensions similar to the anterior drawer, and Lachman maneuvers.

Return to play: this is a controversial area with no definite criteria on return to sports, either timing or type of sports involved. Previously, there was an agreement that return should not be earlier than nine months postoperatively. However, patients should be able to demonstrate the ability to perform certain sport-specific activities and complete a series of functional tests such as various single- and double-leg hopping and jumping. Dynamic valgus has been shown to increase the risk of ipsilateral and contralateral rupture.

Re-rupture: Higher rates have been reported with early return to sport before clearance, which is ideally a joint decision between surgeon and patient.

For injury prevention, certain factors can be employed with particular reference to female athletes who might benefit from neuromuscular training, plyometrics (jump training), training to land from jumping in less valgus and more knee flexion, in addition to increasing hamstring strength to decrease quadriceps dominance ratio.

Advanced Updates on Postoperative Rehabilitation

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES): multiple studies assessed the outcomes of Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) following ACLR.[53][54][55]

A significant clinical effect was demonstrated by adding 2 to 6 sessions of NMES per week to standard rehabilitation protocol, with improved quadriceps strength in the first 4 to 12 weeks postoperatively.[53]

Open Kinetic Chain Exercises: No significant differences were reported with regard to knee laxity, the strength of the muscle, and self-reported function and physical function between the two measures at any follow-up time (4 weeks to 19 months), regardless of the graft type. No difference between the early (< 4 weeks) versus delayed (12 weeks) start of the open kinetic chain exercises with knee flexion limited to a range of 45 to 90 degrees of flexion.[56][57]

No superiority was reported for structured in-person rehabilitation versus structured home-based rehabilitation for quadriceps and hamstring muscle strength, knee laxity, and functionality in both the short and long term following injury and surgery.[58]

Knee bracing following ACLR was found to be not advantageous for knee laxity and physical function.[59]

Preoperative rehabilitation of muscular strengthening and neuromuscular stability training for 3–6 weeks improves self-reported and physical function three months postoperatively, but it does not affect the return to sports outcomes.[60]

Cryotherapy with cold compression devices in the first 24 to 48 hours post-ACLR reduces pain and limits analgesic use compared to no cryotherapy.[61][55]

Following ACLR, Low to very low levels of evidence supports psychological interventions, whole body vibration, protein-based supplement use to improve quadriceps volume and strength, blood flow restriction training to improve quadriceps size and lean muscle mass, neuromuscular control exercises, and continuous passive motion.[62][63][64][65][66][65][64][62]

Pearls and Other Issues

Return to activity is variable and patient-dependent. The average return to full activity and/or sports participation is estimated to be between 6 to 12 months after surgical reconstruction, depending upon their progress with PT and the type of sport/activity to which they are returning. However, some studies have shown that the graft takes up to 18 months or more to become fully functional and incorporated. Early/premature return to activity can lead to re-injury and graft failure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of ACL are best by an interprofessional team that includes an emergency department clinician, orthopedic surgeon, sports clinician, nursing staff, and physical therapist. The initial treatment of ACL is RICE therapy. Depending on their severity, ACL injuries can be managed nonoperatively or operatively.

The patient with an anterior cruciate ligament injury should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon to discuss treatment options and a physical therapist (PT) for rehabilitation. Care coordination between PT and the treating clinician is often the task of a specialty-trained orthopedic nurse, who can also counsel the patient on their condition and treatment. The outcomes for patients with ACL injury are good, but the recovery may take at least 3 to 9 months of intense physical therapy.[3][67]