Continuing Education Activity

A liver abscess is defined as a pus-filled mass in the liver that can develop from injury to the liver or from an intra-abdominal infection disseminated from the portal vein. The majority of these abscesses are categorized as pyogenic or amoebic, although a minority are caused by parasites and fungi. Although the incidence of liver abscess is low, it is essential to early detect and manage these lesions, since there is a significant mortality risk in untreated patients. This activity describes the pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of liver abscess and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the different methods of classifying a liver abscess.

- Describe clinical symptoms consistent with a liver abscess.

- Explain how to systemically and non-invasively evaluate liver abscess.

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the recognition and management of liver abscess and improve outcomes.

Introduction

A liver abscess is defined as a pus-filled mass in the liver that can develop from injury to the liver or an intraabdominal infection disseminated from the portal circulation.[1] The majority of these abscesses are categorized into pyogenic or amoebic, although a minority is caused by parasites and fungi. Most amoebic infections are caused by Entamoeba histolytica. The pyogenic abscesses are usually polymicrobial, but some organisms are seen more commonly in them, such as E.coli, Klebsiella, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and anaerobes. While the incidence is low, it is essential to understand the severity of these abscesses because of the high mortality risk in untreated patients.[2]

The usual pattern of abscess formation is that there is leakage from the bowel in the abdomen that travels to the liver through the portal vein. Many cases have an infected biliary tract that causes an abscess via direct contact.

Liver abscesses can be classified in a variety of ways: One is by location in the liver. 50% of solitary liver abscesses occur in the right lobe of the liver (a more significant part with more blood supply), less commonly in the left liver lobe or caudate lobe. Another method is by considering the source: If the cause is infectious, the majority of liver abscesses can be classified into bacterial (including amebic) and parasitic sources (including hydatiform cyst).

Etiology

Appendicitis used to be the main reason why people develop a liver abscess, but that has decreased to less than 10% since better diagnosis and management of the disease has become available. Nowadays, biliary tract disease (biliary stone, strictures, malignancy, and congenital anomalies) are the major causes of pyogenic liver abscesses.

Half of the bacterial cases are developed by cholangitis. Less often, causes are hepatic artery bacteremia, portal vein bacteremia, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, or penetrating trauma.[3] Some may be from a cryptogenic origin. The most common organisms include E.coli, Klebsiella, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and anaerobic organisms but are generally polymicrobial. If strep or staph is isolated solely, the focus should be on finding another source of infection (endocarditis) that has hematogenously spread to the liver. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a prominent etiology in Southeast Asia and is thought to be related to or associated with colorectal cancer there as well.[4][5] It is usually present with no hepatobiliary system disease and is exclusively monomicrobial. It happens in a background of diabetes and is more severe than other forms of bacterial abscesses, possibly because of enhanced virulence factors of the bacteria.[6]

If the source is an anaerobe, the most common organism is Entamoeba histolytica. It affects the liver by first causing amebic colitis, then seeding the portal system and migrating to the liver and causing an amebic liver abscess. Although rare in the United States, it can still be found in immigrants or travelers from other countries.

Another rare but important parasitic organism is Echinococcus granulosus, which causes a hydatid cyst of the liver. Infection is caused by the metacestode stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus which is part of the Taeniidae family. Patients typically present with symptoms that include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hepatomegaly. Hydatid cysts are acquired from dogs and can take a while to cause symptoms in the host. Most cases are discovered in the late stages and incidentally.[7]

Epidemiology

The annual incidence rate is about 2.3 cases per 100,000 people. Males are more frequently affected than females.[8] Age plays a factor in the type of abscess one develops. People aged 40-60 years are more vulnerable to developing liver abscess that does not result from trauma.

A significant number of liver abscesses are reported to be pyogenic. Abbas et al. noted that of 67 patients admitted for liver abscesses in the Middle East, 56 were due to pyogenic causes with most cases due to Klebsiella pneumonia.[9] Sixty-one of those patients were males. The incidence in Taiwan seems to be very high (17.6 per 100,000).[10] Pyogenic hepatic abscess constitutes about half of all visceral abscesses and 13% of intraabdominal ones.[11]

Pathophysiology

The gastrointestinal tract of humans is formed from the mesoderm, ectoderm, and endoderm. The endoderm forms the lining of the tube. The posterior splanchnic vessels fuse to form the dorsal mesentery. Anterior splanchnic vessels fuse to form ventral mesentery. The liver is developed in the septum transversum, which is enclosed by the ventral mesentery. The liver retains its attachment with the anterior abdominal wall.

Since the liver receives its blood circulation from the systemic and portal circulations, it is more susceptible to getting infections and abscesses from the bloodstream.[12] Proximity to gall bladder is another risk factor for the liver. On the other hand, since Kupfer cells surrounding the liver are protective of the parenchyma, getting infections or abscess formation might not happen that frequently or as quickly as expected either.

The usual pathophysiology for pyogenic liver abscesses is bowel content leakage and peritonitis. Bacteria travel to the liver via the portal vein and resides there. Infection can also originate in the biliary system. Hematogenous spread is also a potential etiology.

Histopathology

Liver abscesses are not a common condition. They can arrive either from an ischemic episode or by bacteria entering through the portal vein, as mentioned.[13] Septic emboli cause several microabscesses which combine to form one large abscess. Hematogenous spread from endocarditis or pyelonephritis can happen. While these are more common in adults, in children, chronic granulomatous disease and leukemia are a culprit for liver abscess formation.

Trauma (penetrating or nonpenetrating) can cause bacterial abscesses in both populations (adults and children). Penetration introduces bacteria directly, whereas nonpenetrating events can cause hemorrhage, necrosis, bile leakage, ultimately resulting in abscess formation.

Abscesses are also caused by parasites, malignancy, foreign bodies, or complications from liver transplants. [14][15][16]

History and Physical

It is vital to obtain a thorough history and carry out a detailed physical examination before choosing any diagnostic measures. This includes but is not limited to, gathering the patient’s personal history, occupation, travel, place of origin, recent infections, or treatments. Certain risk factors promote the development of liver abscesses, such as diabetes, cirrhosis, male gender, elderly, immunocompromised states, and people with proton pump inhibitor usage.

After gathering a history, the review of systems and physical examination can provide a lot of additional information. On analysis of systems, patients may complain of the following symptoms: fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, nausea or vomiting, right shoulder pain (due to phrenic nerve irritation), right upper quadrant pain, cough, dyspnea, anorexia, or recent unexplained weight loss. Fever is present in 90% and abdominal pain in about 50-75% of patients.[17] Dark urine is present, much like it is present in other forms of hepatitis.

On physical examination, a patient can have hepatomegaly with an enlarged mass and jaundice. Although Charcot triad (right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and fever) is a sign of cholangitis, the physician will need to consider liver abscess as a differential.[18] A small number of patients with hepatic abscesses may present in distress or even overt shock (septic shock or anaphylactic shock in the case of the hydatiform mole rupture).

In the case of Klebsiella liver abscesses, in addition to the symptoms mentioned above, it also sends septic emboli to the eye, meninges, and brain. Therefore symptoms of these organ systems can be present, and it can last after the liver abscess is drained.

In the case of Echinococcus infection, there is an initial asymptomatic phase in a child. Years later, some of these patients will show clinical symptoms from reactivation of the infection.[19] The clinical manifestations depend on the type, size, and site of the cysts present. Small cysts in non-vital organs can go undetected, but large ones in critical locations can present with signs of compression or rupture.[20] The usual rate of cyst progression is 1 to 5 centimeters in a year. The liver is affected in two-thirds of cases of Echinococcus infection. Symptoms of compression usually start when the diameter is 10 cm and include biliary colic, cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, portal and venous obstruction, Budd-Chiari syndrome, bronchial fistula, If it ruptures, overt peritonitis or anaphylaxis will be present.

Evaluation

After the history and physical examination, the next step is to obtain laboratory and diagnostic evidence to determine the cause of the patient's chief complaint and confirm or rule out a liver abscess. Laboratory tests include a complete blood count with differential, tests for hepatocellular injury (liver enzymes that are usually elevated in half the cases), liver synthetic function tests (Prealbumin and INR), alkaline phosphatase (elevated in around 90% of patients), C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood cultures to rule out bacteremia.[21]

If an amebic abscess is suspected (such as in residents or travelers from Southeast Asia, Africa, etc.), stool test or serology for Entamoeba histolytica should be performed. For the hydatid cyst, serology for Echinococcus is needed. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) seems to be the most sensitive and specific for Echinococcus. After initial screening with ELISA, confirmatory tests with immunoelectrophoresis and immunoblotting are needed. Serology positivity is dependant on the size and site of the cysts. Liver and bone cysts produce positive serology, whereas lung, brain, eye, splenic, or calcified cysts do not. Calcification is usually a sign of non-viable material.

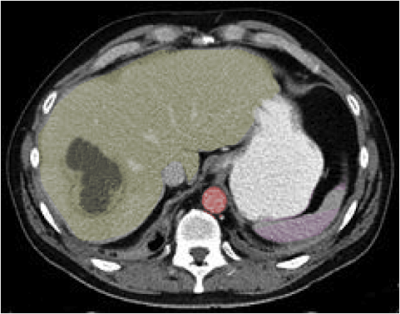

Many radiographical tests can be performed, and certain tests should take precedence. It is important to limit a patient's exposure to unnecessary radiation and tests. There can be findings in the chest x-ray, pointing to this diagnosis, such as elevated hemidiaphragm on the right and pleural effusion over the liver. However, the initial test of choice is an abdominal ultrasound (US), which shows hyper or hypoechoic lesions with occasional debris or septation. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast is the next step, and slightly more sensitive. Rim enhancement and edema are not typical but very specific for infection. The US or CT is followed by needle aspiration under guidance to identify the exact causative organism, which is essential for diagnostic as well as therapeutic purposes (small cysts).[22] Technetium scan is another test with an 80% sensitivity (less than CT), which is 50-80% for gallium and 90% for indium.[23][24] If inner cyst walls are in-folded (separation of hydatid membrane from the wall of the cyst) during the US, hydatid disease is more likely.

Stains and cultures should be obtained from the direct aspirate. Drains that are in place will get contaminated with skin flora and are not accurate for cultural purposes. Stains and cultures should be done for aerobes and anaerobes (special handling might be needed), but occasionally more specific cultures need to be done, such as fungi, Mycobacterium, Entamoeba histolytica, and parasites.

Diagnosis is confirmed when there are cystic or solid areas in the liver that, upon aspiration, will yield fluid with positive cultures. It is important to obtain these tests quickly and start treatment because of the high complication rate if left untreated.

Treatment / Management

Drainage of the abscess and antibiotic treatment are the cornerstones of treatment.

Drainage is needed and can be done under the US or CT. Needle aspiration (at times repeatedly) might be all that is required for abscesses less than 5 cm, but a catheter placement might be warranted if the diameter is more significant than that.[25] [26] Percutaneous drainage with catheter placement is probably the most successful procedure for larger than 5 cm abscesses.[27] Laparoscopic drainage is also used at times. Surgery should be done for peritonitis, thick wall abscesses, ruptured abscess, multiple large abscesses, and previously failed drainage procedures. An operation is performed either by a transperitoneal approach or by the posterior transpleural approach. The former approach drains the abscess and allows for the exploration of undetected ulcers, while the latter is better for posterior abscesses. Size, location, and stage help determine a successful treatment plan. When previous biliary procedures have been done, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) drainage might be used.[28] Undrained liver abscesses may cause sepsis, peritonitis, and empyema.

Empiric antibiotic coverage is essential when the organism is unknown. The antibiotics should cover Enterobacteriaceae, anaerobes, streptococci, enterococci, and Entamoeba histolytica. Such antibiotic regimens include cephalosporins plus metronidazole, Beta-lactam Beta-Lactamase inhibitor plus metronidazole, or synthetic penicillins plus aminoglycosides and metronidazole. Alternatively, fluoroquinolones or carbapenems can be substituted for cephalosporins or penicillins in case of allergy or unavailability. Metronidazole should cover Entamoeba histolytica. The duration of treatment varies but is usually from two to six weeks. After initial intravenous treatment, the oral route can be used safely in most cases to complete the course. Culture results help narrow down the organism, so empiric treatment is no longer needed, as it can lead to antibiotic resistance. Anaerobes are hard to culture, so sometimes they should be treated for the entire course empirically. For stable patients, antibiotics can be given post-drainage to increase culture yield for proper treatment. Empiric antifungal treatment is crucial in immunosuppressed patients with a risk for chronic disseminated fungemia. Occasionally if the patient is too sick for drainage, antibiotics are used solely for treatment, but this is a less desirable method.

If the source is Echinococcus, treatment includes a benzimidazole, such as albendazole. This therapy may last for several years. Although most cases are uncomplicated and can be treated with an antiparasitic drug, complicated cases must be treated delicately. In most complicated cases, drainage is necessary. Surgeons must take caution to inject the hydatid cysts before draining them, as sometimes the rupture can cause the patient to go into shock rapidly.

In a study by Abbas, the mean duration of hospital stay for those with pyogenic liver abscesses was 13.6 days. Antibiotic therapy used for them was approximately 34.7 days. One patient expired. On the other hand, patients with amebic liver abscesses had a mean hospital stay of approximately 7.7 days, with a mean duration of treatment of 11.8 days, where all patients were cured. [9]

Differential Diagnosis

Liver abscess manifests with right upper quadrant pain, fever, and hepatitis. Therefore many liver and non-liver ailments are in its differential diagnoses, such as:

- Viral hepatitis

- Cholecystitis

- Cholangitis

- Right lower lobe pneumonia

- Appendicitis

- Necrotic liver masses

Other causes of hepatitis such as autoimmune, drug-induced and acetaminophen toxicity can be mistaken although they are usually not painful.

Prognosis

With new techniques available for drainage and antibiotics specific for appropriate organisms, liver abscesses have a much better prognosis now. In-hospital mortality is estimated at 2.5% to 19%.[29] The mortality rate is higher in elderly, ICU admissions, shock, cancer, fungal infections, cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, acute respiratory failure, severe disease, and biliary origin of an abscess. Liver abscess recurrence is frequent in patients who present with a biliary tract disease.[30]

In hydatic cysts, the prognosis is good. 57% will have a stable cyst, and even if the cyst grows, it will not usually cause symptoms. About 15% will require surgery, and that is often years after diagnosis. 76% of those who do not have surgery remain asymptomatic for years.[20]

Complications

If untreated, hepatic abscesses can rupture, cause peritonitis and shock. At times the area will get walled off, and chronic pain and discomfort in the right upper quadrant with occasional nighttime fever can follow. Complications are also possible after drainage and include liver or kidney failure, intraabdominal lesions, infections, or recurring liver abscesses.[31] Other complications include subphrenic abscess, fistula to organs nearby (such as pleuropulmonary and hypobranchial fistula), acute pancreatitis, abdominal or hepatic venous thrombosis, and liver pseudoaneurysm. Infectious metastatic complications include endophthalmitis or central nervous system septic emboli.

It is vitally important to follow up with patients after treatment to prevent and recognize some of these complications. Immediate treatment for intraabdominal infection is the best preventive measure for liver abscesses. Four to six weeks of antibiotic therapy post-drainage can prevent almost any complications. Antibiotic prophylaxis during chemoembolization or endoscopic retrograde cholangiography help in the prevention of future abscess formation.

Radiographic abnormalities will take longer than clinical or lab abnormalities to go away, as is with many other medical problems. So enough time should elapse before the graphs go back to normal.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative prevention includes the continuation of antibiotics, checking blood count, renal function, bilirubin, and aminotransferases.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Avoidance of animal saliva or feces to prevent hydatid cysts can prevent some cases caused by the Echinococcus species.[7][32] Physicians can teach patients to take simple precautions to reduce the risk of acquiring liver abscess. Most cases are not life-threatening, but some culminate in high mortality rates from complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Liver abscesses are not as common now as they used to be. It is imperative to differentiate between the two most common sources for liver abscesses, pyogenic or amebic, and to treat them upon discovery.

Drainage plus antibiotics/antifungals are needed. Understanding the pathophysiology of liver abscesses is crucial because it aids in the diagnosis of the patient’s presenting symptoms.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are many causes of liver abscess, and thus the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team of primary care physicians, nurses, radiologists, surgeons, infectious disease specialists, and pharmacists who are needed for treatment of hepatic abscesses. The size and location of the abscesses determine the type of management. Non-invasive measures take priority. Today percutaneous drainage and antibiotics suffice for most liver abscesses.