Continuing Education Activity

Ludwig angina is life-threatening cellulitis of the soft tissue involving the floor of the mouth and neck. Ludwig angina involves 3 compartments of the floor of the mouth: sublingual, submental, and submandibular. The infection is rapidly progressive, leading to potential airway obstruction. The most common etiology is a dental infection in the lower molars, mainly second and third, accounting for over 90% of cases. Any recent infection or injury to the area may predispose the patient to develop Ludwig angina. Predisposing factors include diabetes, oral malignancy, dental caries, alcoholism, malnutrition, and immunocompromised status. This review addresses the management and acute treatment of this possibly lethal condition.

Objectives:

Identify and recognize the clinical signs and symptoms of Ludwig angina.

Implement appropriate diagnostic modalities to aid in the diagnosis and assessment of Ludwig angina.

Apply evidence-based treatment strategies for Ludwig angina, including airway management, antibiotic therapy, and surgical intervention.

Collaborate with all members of the interprofessional team, including specialists such as otolaryngologists, anesthesiologists, and oral maxillofacial surgeons, to provide efficient, comprehensive, and coordinated care.

Introduction

Ludwig angina is an uncommon life-threatening diffuse cellulitis of the soft tissue of the floor of the mouth and neck. The condition is named after a German physician, Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, who described it in 1836. Angina comes from the Latin "angere," meaning to choke.[1]

Ludwig angina involves 3 compartments of the floor of the mouth: sublingual, submental, and submandibular. Infection of the lower molars is the hallmark cause of true Ludwig angina; however, this term is frequently applied to any floor-of-the-mouth infection with sublingual or submandibular space involvement.[2] It rapidly progresses to the surrounding tissues, leading to potentially lethal complications, such as airway obstruction, aspiration pneumonia, and carotid arterial rupture or sheath abscess.[3] Therefore, early recognition and treatment, including airway protection, antibiotic therapy, and surgical drainage in well-established infections, are crucial.

Etiology

Ludwig angina mainly originates from dental infections in the mandibular molars, particularly the second and third molars, accounting for 90% of cases.[4] Periapical abscesses in the second or third mandibular molars are primarily responsible for the condition.[5]

Other less common etiologies include oral piercing or laceration, mandibular fracture, traumatic intubation, osteomyelitis, peritonsillar or parapharyngeal abscess, submandibular sialadenitis, otitis media, and infected thyroglossal cysts.[3][6][7]

Predisposing dental factors include poor oral hygiene, dental caries, and recent dental treatment.[5] In most cases, Ludwig angina develops in previously healthy patients; however, some predisposing factors have been suggested, including diabetes, alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, and immunosuppression, such as in patients with AIDS or who have received an organ transplant.[2][8]

Epidemiology

Ludwig angina does not show a significant gender predilection. Airway compromise is the leading cause of mortality.[5] Before the development of antibiotics, mortality exceeded 50%.[7] Rapid airway management, antibiotic therapy, advanced imaging, and surgical procedures have decreased mortality to around 8%.[9]

Pathophysiology

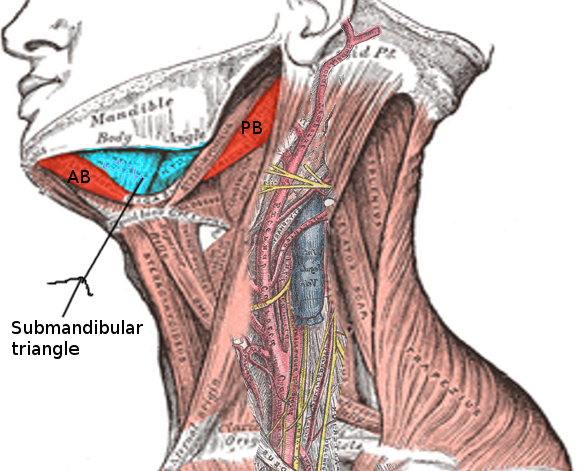

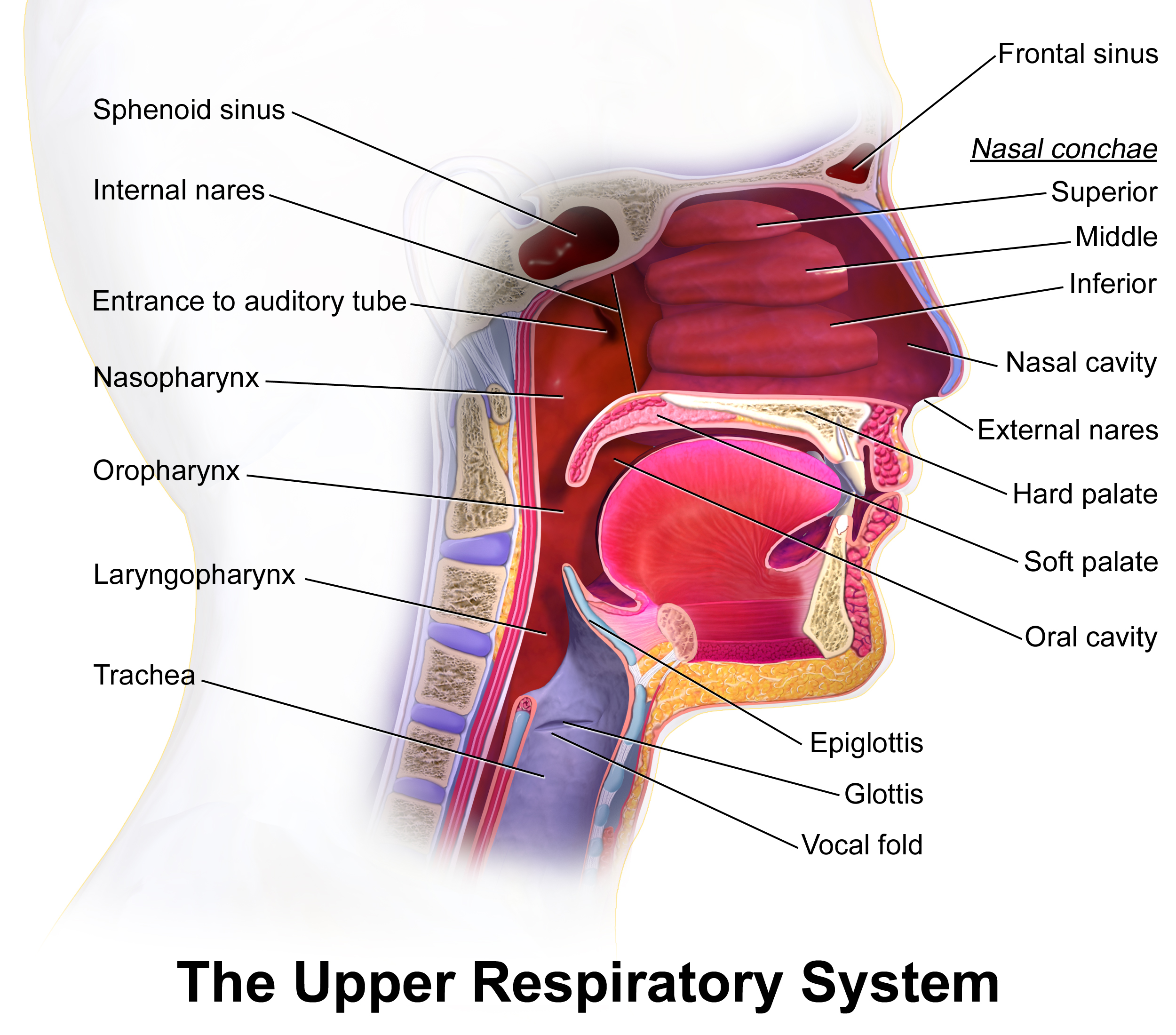

Knowledge of regional anatomy is essential for comprehending how the spread of the infection takes place. Ludwig angina typically initiates at the floor of the mouth and rapidly extends to the submandibular space.[10] The floor of the mouth is divided by the mylohyoid muscle into the sublingual space above the muscle and the submandibular space below the muscle. The roots of the mandibular molars are located inferior to the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle, which allows the spread of odontogenic infections into the submandibular space.[5] Extension of the infection to these 2 spaces may enlarge or elevate the tongue and obstruct the airways if there is no intervention.[5] The infection may also result in edema of the airway structures (epiglottitis, vocal cords, and aryepiglottic folds), which can occur after half an hour of initial presentation.[5]

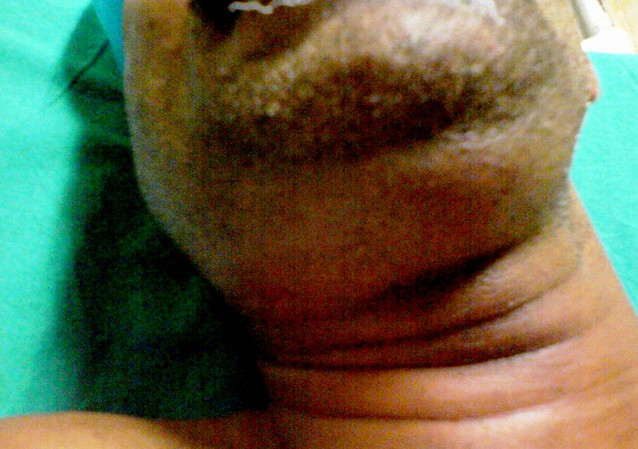

The infection may eventually extend to the parapharyngeal space, retropharyngeal space, and superior mediastinum via the styloglossus muscle.[10] The infection spreads to the neck throughout the spaces between the fascial layers and not through the lymphatic system.[10] The progression of the infection to the neck is often seen clinically as a "bull neck."[10]

Microbiology

The disease is usually polymicrobial and involves oral flora, both aerobes and anaerobes. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Actinomyces are the most common organisms.[11] Infection with Streptococcus anginosus progresses the disease more rapidly than other bacteria.[12] Cultures from more than half of patients presenting with Ludwig angina who have diabetes show Klebsiella pneumoniae.[10] Patients with diabetes, hemodialysis, and recent hospitalization (within a year) are at increased risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection.[5]

History and Physical

Patients may report a history of recent dental pain. The most commonly reported symptoms are fever, fatigue, chills, and weakness. Trismus is another typical complaint, which indicates a more advanced stage of the disease—the extension of the infection to the parapharyngeal space.[5] Signs of respiratory involvement include tripod positioning, drooling, and dysphagia.[5] Other signs or symptoms include mouth pain, hoarse voice, drooling, tongue swelling, and stiff neck.[9]

The clinical aspect of the condition is often described as a "bull neck," with increased fullness of the submental area and a loss of mandibular angle definition. On examination, patients usually have a fever with submental and submandibular swelling and tenderness. Swelling of the floor of the mouth, elevation of the tongue, and tenderness of the involved teeth are oral signs of infection. The induration of the submental neck and edema in the upper part of the neck are common extraoral findings, although the patient will not typically have lymphadenopathy.[7]

Evaluation

Ludwig angina is primarily diagnosed based on clinical evaluation. Imaging studies do not play a direct role in the immediate assessment of the patient. In cases with a compromised airway, the decision to intubate is based solely on clinical parameters, as delaying treatment to send the patient for a CT scan can delay treatment. Once the airway is secured, a neck CT with intravenous contrast is the most appropriate imaging modality to evaluate the severity of the infection and assess for abscess.[13] CT scan findings suggesting Ludwig angina may include soft tissue gas, fluid cumulus, muscle edema, attenuated subcutaneous fat, loss of fat planes in the submylohyoid space, and soft tissue thickening.[5] Ultrasound and point-of-care ultrasound can be helpful tools to detect Ludwig angina and assess the airways.[5]

Although common in clinical practice, laboratory testing holds little immediate value in the diagnosis of Ludwig angina since it primarily relies on clinical assessment. Blood cultures should be obtained to determine if the infection has a hematogenous spread. Obtaining cultures from the affected area through swab or needle aspiration has limited diagnostic value in cases of Ludwig angina.[5]

Treatment / Management

The primary objective in treating Ludwig angina is to secure the airway, as asphyxiation resulting from airway obstruction is the leading cause of mortality. The next steps include controlling the infection with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical drainage in some cases of well-established infections. Intravenous steroids and nebulized adrenaline can be adjuvant treatments to improve facial and airway edema and antibiotic penetration.[3][5]

Airway Management

If hypoxic, patients must receive supplemental oxygen.[5] Neck swelling usually complicates mask ventilation; therefore, pre-oxygenating patients using any approach is crucial.[5] Tongue elevation and trismus complicate the placement of an oropharyngeal airway. Flexible nasotracheal intubation is the favored method of intubation, but arrangements for a surgical airway like cricothyrotomy must be in place before any attempt on airway intervention.[14] It is recommended that patients are intubated in a seated position and awake, using a flexible intubating endoscope.[15] Flexible nasotracheal intubation requires an experienced physician; if not possible, a cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy is sometimes performed as an emergency maneuver in the advanced stages of the infection.[16] Managing the airway before stridor or cyanosis is vital, as these are late findings.

Blind nasotracheal intubation, which involves passing an endotracheal tube without a direct view of the larynx, should be avoided in cases of Ludwig angina. This procedure can potentially induce bleeding, rupture abscesses, exacerbate edema, and lead to laryngospasm.[5][16] Supraglottic airway devices may be displaced due to the progression of the swelling; these devices must be avoided.[5]

Intravenous Antibiotics

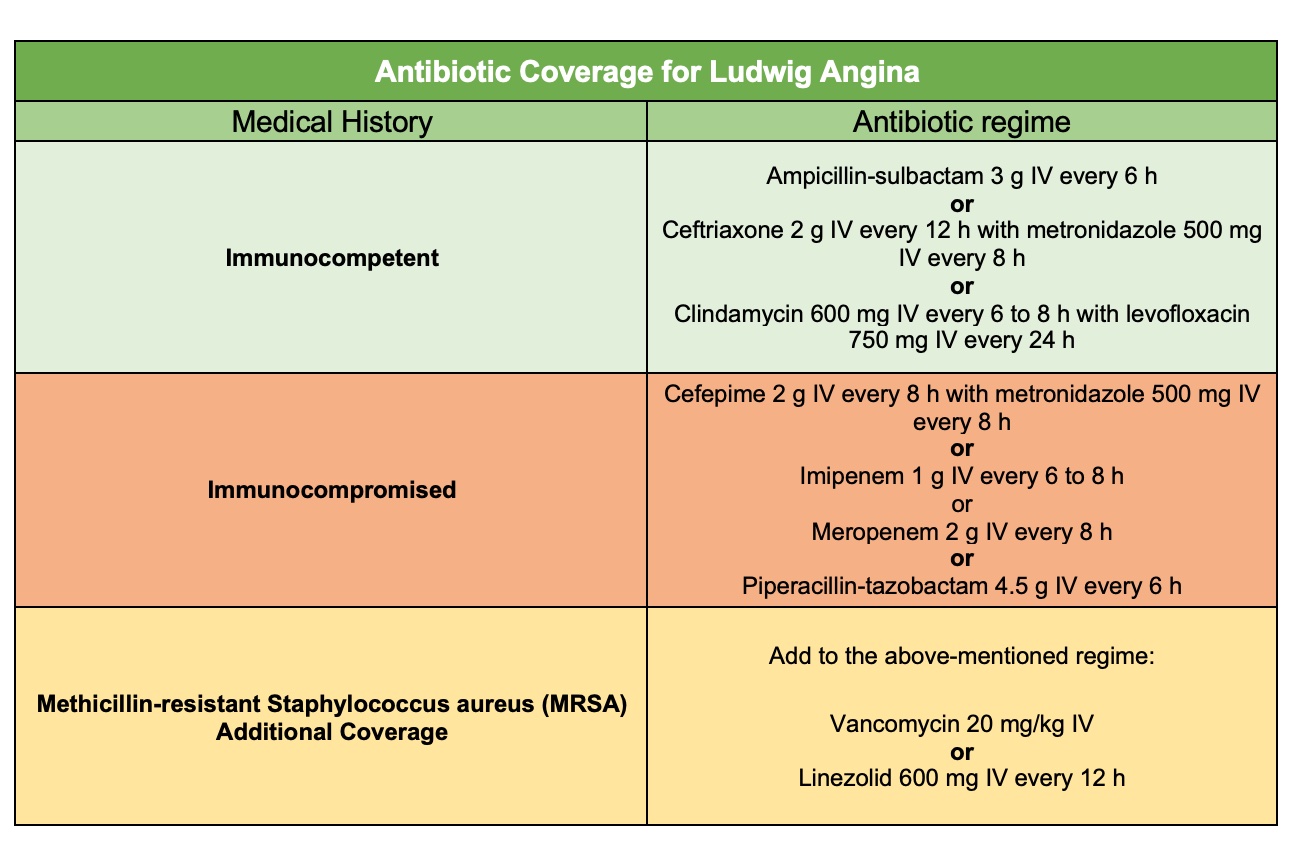

Once the airway is secured, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics serve as the first-line treatment.[7] Antibiotics should cover aerobic, anaerobic, and oral microflora.[5] Ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin are the most commonly prescribed antibiotics. In immunocompromised patients, the antibiotic coverage should include gram-negative rods and beta-lactamase-producing aerobes and anaerobes. Some options include cefepime, meropenem, or piperacillin-tazobactam.

Furthermore, clinicians should consider MRSA coverage for immunocompromised patients, those at increased MRSA risk, or those with prior history of MRSA infection. MRSA coverage includes the addition of vancomycin IV or linezolid IV to the mentioned antibiotic coverage.[7] Table 1 summarizes the recommended antibiotic regimes (see Media File 4).[5]

Intravenous Corticosteroids

Intravenous steroids and nebulized adrenaline (epinephrine) can be used as adjuvant treatment, reducing edema and cellulitis, facilitating intubation, and increasing the penetration of antibiotics into the fascial spaces.[3] Several case reports have shown a decrease in the need for airway management with the use of steroids.[6] Dexamethasone (10 mg IV) is the most common steroid used for these cases.[5] However, more studies are needed before the use of steroids becomes a standard of care, and the use of steroids is left to the treating physician's discretion. Even though the evidence is limited, nebulized epinephrine may also potentially decrease airway obstruction.[5]

Surgical Drainage

Although the evidence is controversial, early surgical decompression of the submandibular space may improve airway status.[5] The surgical intervention aims to reopen the oropharyngeal airway by allowing the tongue to move into a more anteroinferior position.[17] The incision is usually made parallel and at 2 fingerbreadths inferior to the mandibular angle, and, in some cases, many incisions are needed. The following steps include displacing the submandibular gland and dividing the mylohyoid muscles to decompress the affected fascial compartments.[8] Surgically decompressing the floor of the mouth could avoid the need for prolonged airway intubation and decrease the overall hospital length of stay.[17] Furthermore, it is a safe procedure with no reported direct complications.[17]

Surgical decompression is indicated in cases of Ludwig angina when there is a visible abscess on imaging, the presence of fluctuance on examination, or when antibiotic treatment has proven ineffective.[18]

Differential Diagnosis

While Ludwig angina is primarily diagnosed based on clinical evaluation, it can initially pose challenges distinguishing it from other diseases. Imaging may be helpful in this situation to rule out other causes. Imaging evaluation should only be performed after securing the airway or in patients who can breathe comfortably and manage their secretions while in a supine position.

Prognosis

Prior to the advent of antibiotics, the mortality rate of Ludwig angina exceeded 50% due to the life-threatening complication of airway obstruction.[7] With the advancements in antibiotic therapy, improved imaging modalities, and surgical techniques, the mortality rate of Ludwig angina has significantly decreased to approximately 8%.[9]

Complications

As mentioned, Ludwig angina is a rapidly progressive cellulitis that can cause airway obstruction requiring immediate intervention. The presence of airway symptoms or the inability to manage oral secretions are clear indications for elective intubation in order to prevent potential mortality in cases of Ludwig angina.

Furthermore, close monitoring is essential to prevent the spread of cellulitis to adjacent areas, which can lead to complications such as mediastinitis or neck cellulitis. Additionally, Ludwig angina can progress to aspiration pneumonia. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis, occurring predominantly through the retropharyngeal space (71%) or the carotid sheath (21%), is a severe complication that requires attention.[6] Sepsis resulting in multiple organ failure is common, particularly in immunocompromised patients.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Odontogenic infection is the leading cause of Ludwig angina. Providing safety education to patients with dental infections is vital in mitigating the risk of severe complications.[1] Red flag symptoms that may indicate worsening swelling and potentially necessitate emergency management include:[1]

- Significant mouth-opening restriction

- Bilateral submandibular swelling

- "Hot potato" voice

- Fever

- Firm or swollen floor of the mouth

- Restricted tongue mobility

- Swallowing difficulty

- Drooling

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ludwig angina is a rapidly progressive cellulitis that can quickly cause airway obstruction. Risk factors for increased mortality and complications are age older than 65, immunosuppression, diabetes, and alcohol consumption.[5] The condition requires immediate intervention and close monitoring to prevent death from asphyxiation. It can also result in mediastinitis, necrotizing cellulitis of the neck, and aspiration pneumonia.

Due to the rarity of the condition, many emergency physicians have limited experience in managing Ludwig angina.[6] Securing and maintaining the airway is the primary objective for all Ludwig angina patients.[6] Immediate involvement of the otolaryngology, anesthesiology, or oral maxillofacial teams is crucial to provide the best possible outcome and ensure patient safety. [Level 5]