Continuing Education Activity

Low back pain is a prevalent symptom, as approximately 80 % of the population sustains an episode once in their lifetime. Within the many differentials of low back pain, the most common cause is the intervertebral degeneration which leads to lumbar disc herniation and degenerative disc disease. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of lumbar disc herniation and discusses the role of the healthcare team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of lumbar disc herniations.

- Review the proper steps in the evaluation of lumbar disc herniations.

- Outline the management options available for lumbar disc herniations.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to improve outcomes of lumbar disc herniations.

Introduction

Lower back pain (LBP) is one of the most common presenting complaints globally, as approximately 80% of the population sustains an episode once in their lifetime. This highly prevalent and disabling ailment costs more than $100 billion annually in the United States. Among the many differential diagnoses of LBP, degenerative disc disease and lumbar disc herniation (LDH) are the most common. Approximately 95% of disc herniations in the lumbar area occur at L4-L5 or L5-S1.[1]

The lumbar spine contains five vertebrae and intervertebral discs, producing a lordotic curve. The intervertebral discs with the laminae, pedicles, and articular processes of adjacent vertebrae create the space in which the spinal nerves exit.[2] The intervertebral discs consist of an inner nucleus pulposus (NP), outer annulus fibrosus (AF), and the cartilaginous endplates that anchor the disc to its vertebras.

The nucleus pulposus is a gel-like structure that is composed of approximately 80% water, with the rest made by type 2 collagen and proteoglycans. The proteoglycans include the larger aggrecan, which is responsible for retaining water within the nucleus pulposus. Also, it provides versican that binds to hyaluronic acid. This hydrophilic matrix is responsible for maintaining the height of the intervertebral disc.

The annulus fibrosus is a ring-shaped structure that surrounds the nucleus pulposus. It is made of highly organized fibrous connective tissue, consisting of 15 to 25 stacked sheets of predominantly collagen lamellae with interspersed proteoglycans, glycoproteins, elastic fiber, and the connective tissue cells that secreted these extracellular matrix products. The inner part of the annulus fibrosus is predominantly made of type 2 collagen, while the outer part is mostly of type 1 collagen.[3]

Etiology

Disc degeneration is usually associated with disc herniation. With aging, the disc fibrochondrocytes undergo senescence and a reduction in proteoglycans production. This reduction in proteoglycans leads to dehydration and disc collapse, increasing the strain on the annulus fibrosus, resulting in tears and fissures, and consequentially facilitating the nucleus pulposus herniation. Therefore, when repetitive mechanical stressors are applied on the disc, it results in a gradual onset of symptoms that tend to be chronic.

On the other hand, axial overloading applies a large biomechanical force on the healthy disc, which may result in extrusion of disc material through a failing annulus fibrosus. Those injuries usually result in more severe acute symptoms.[4] Other less common causes are connective tissue disorders and congenital disorders like short pedicles.[5]

Epidemiology

Lumbar disc herniation is relatively common, with 5 to 20 cases per 1000 adults annually. LDH is most prevalent in the third to the fifth decade of life, with a male to female ratio of 2 to 1.[6]

Pathophysiology

Lumbar disc herniation results from several changes in the intervertebral disc including reduced water retention in nucleus pulposus, increased type 1 collagen ratio in the nucleus pulposus and inner annulus fibrosus, destruction of collagen and extracellular material, and an upregulated activity of degrading systems such as matrix metalloproteinase expression, apoptosis, and inflammatory pathways. Ultimately, resulting in a local increase in inflammatory chemokines and mechanical compression applied by the protruding nucleus pulposus on the exiting nerve.

The pressure exerted by the herniated disc on the longitudinal ligament and the irritation caused by the local inflammation results in localized back pain. The lumbar radicular pain arises when disc material exerts pressure or contacts the thecal sac or lumbar nerve roots, resulting in nerve root ischemia and inflammation. The annulus fibrosus is thinner on the posterolateral aspect and lacks support from the posterior longitudinal ligament, making it vulnerable to herniations. Due to the proximity of the nerve root, a posterolateral herniation is more likely to result in nerve root compression.[1][4][5]

In LDH, the narrowing of the space available for the thecal sac is attributable to several factors such as protrusion of the disc through an intact annulus fibrosus, extrusion of the nucleus pulposus through the annulus fibrosus while maintaining continuity of the disc space, or obliteration of the disc space continuity and sequestration of free fragments.[1]

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical examination are essential in the evaluation of a patient with suspected lumbar disc herniation. The principal signs and symptoms include:

- Radicular pain

- Low back pain

- Sensory abnormalities at the lumbosacral nerve roots distribution

- Weakness at the lumbosacral nerve roots distribution

- Limited trunk flexion

- Pain exacerbation with straining, coughing, and sneezing

- Pain intensified in a seated position, as the pressure applied to the nerve root is increased by approximately 40%

The history must include questions about the quality of the pain and the impact on the patient's activity. The mechanism of injury is essential to know. The clinician must ask the patient about any current or past treatments, urinary or fecal incontinence, saddle anesthesia, past medical history of malignancy, inflammatory conditions, systemic infection, immunosuppression, and drug use. Red flag signs that could be features of underlying infection, inflammatory disease or malignancy like fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, extreme pain, and vertebral body point tenderness require investigated.[1][7]

A careful and thorough neurological examination can help to localize the level of lumbar disc herniation if it is causing radiculopathy. The correct knowledge of the anatomy of nerve roots and lumbar disc herniations would allow a proper interpretation of the clinical findings associated with this condition. The radiculopathy associated with LDH varies based on the herniation type and the level at which the herniation occurred. In paracentral or lateral herniation, the transversing nerve root is usually affected; a lateral herniation at L4-L5 would cause L5 radiculopathy. Extreme lateral (far lateral) herniations typically result in the exiting nerve root being affected; extreme lateral herniation at L4-L5 would cause L4 radiculopathy.

L1 nerve root exits at the L1-L2 foramina, assessed with a cremasteric reflex (male). When compressed by a herniated disc, it causes pain, and sensory loss in the inguinal region rarely causes weakness in the hip flexion.

The L2 and L3 nerve roots exit at the L2-L3 and L3-L4 foramina, respectively. Symptoms worsen with sneezing, coughing, or leg straightening.

L4 nerve root exits at the L4-L5 foramina. L4 has a reflex assessed with a patellar reflex. When compressed by a herniated disc, it causes back pain that radiates into the anterior thigh and the medial aspect of the leg, accompanied with sensory loss in the same distribution, weakness in the hip flexion and adduction, weakness in knee extension, and a decreased patellar reflex.

L5 nerve root exits at the L5-S1 foramina. When compressed by a herniated disc, it causes back pain that radiates into the buttock, lateral thigh, lateral calf, the dorsum of the foot, and the great toe. Sensory loss is present on the web space between the big toe and second toe, the dorsum of the foot, and lateral calf. There is a weakness in hip abduction, knee flexion, foot dorsiflexion, big toe dorsiflexion, foot inversion, and eversion. Patients present with decreased semitendinosus/semimembranosus reflex. Weakness in foot dorsiflexion makes it challenging to walk on the heels. Chronic L5 radiculopathy may cause atrophy of the extensor digitorum brevis and the tibialis anterior of the anterior leg.

S1 nerve root exits at the S1-S2 foramina, assessed with the Achilles reflex. When compressed with a herniated disc, it presents with sacral or buttock pain that radiates into the posterolateral thigh, the calf, plantar or lateral foot or the perineum. Sensory loss is present on the calf, lateral, or plantar aspect of the foot. There is weakness on foot plantar flexion, hip extension, and flexion of the knee. Weakness in foot plantar flexion causes an inability to tiptoe walk. It could also cause urinary and fecal incontinence and sexual dysfunction.[5][8][9]

A straight leg raise test is a neurological maneuver performed while examining a patient presenting with lower back pain. It is conducted with the patient lying supine while keeping the symptomatic leg straight by flexing the quadriceps. The examiner slowly elevates the leg progressively at a slow pace. The test is positive when it reproduces the patient's symptoms (pain and paresthesia) at an angle lower than 45 degrees with radiation below the knee (Lasegue sign). It is most helpful in diagnosing L4, L5, and S1 radiculopathies. The patient is asked to dorsiflex the foot while the examiner is raising the leg (Bragaad's sign) to increase the sensitivity of the test.

Another maneuver is the crossed straight leg test, which is similar to the straight leg raise test but is conducted on the asymptomatic leg instead. The crossed straight leg test is considered positive when the patient reports pain in the symptomatic leg, while the asymptomatic leg is at 40 degrees angle, representing a central disc herniation with severe nerve root irritation.[10]

A recent meta-analysis concluded that a clinical diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy, could be made with a straight leg raise screening test, if also Hancock rule requirement is met (having three positives out of the four following findings: dermatomal pain in the nerve root distribution, and associated sensory deficit, reflex abnormality, and motor weakness).[1][11]

Evaluation

Over 85 to 90% of patients with an acute herniated disc experience relief of symptoms within 6 to 12 weeks without any treatments. Patients without radiculopathy notice an improvement in even less time. Due to the high prevalence of disc herniation in routine neuroimaging of asymptomatic individuals, the recommendation is to avoid ordering imaging studies during this period as the study results will not alter the management. However, further evaluation and imaging are warranted if there is a clinical suspicion of severe underlying pathology or neurological compromise. Imaging and laboratory tests are indicated in patients who exhibit red flag symptoms. In patients who are unresponsive to conservative treatment after two to three months, imaging is also recommended.

Laboratory tests: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are inflammatory markers, and they are requested if suspicious for a chronic inflammatory condition or infectious cause as the etiology. A complete blood count is useful when suspecting infection or malignancy.

X-rays: Lumbar X-ray films are the first-line imaging test performed in low back pain settings. The standard examination includes three views (AP, lateral, and oblique) to evaluate the overall alignment of the spine, detecting fractures, as well as degenerative or spondylotic changes. Lateral flexion and extension views are useful in assessing spinal instability. Narrowed intervertebral space, traction osteophytes, and compensatory scoliosis on X-ray are findings that usually suggest lumbar disc herniation. If an acute fracture is detected, further investigation with computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required.

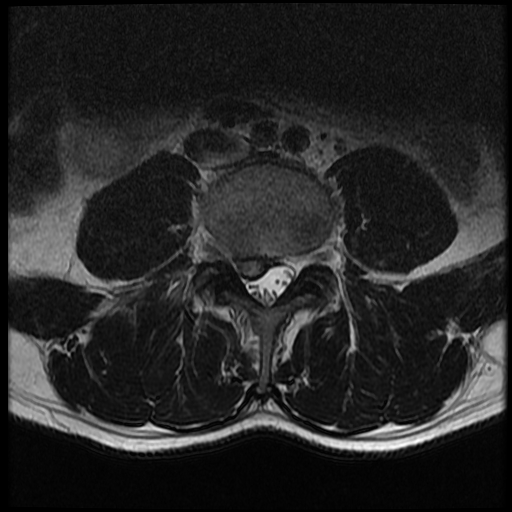

CT: This is the most sensitive imaging modality to examine the bony structures of the spine. CT imaging allows for the evaluation of calcified herniated discs or any pathological process that may result in bone loss or destruction. It is deficient for the visualization of nerve roots, making it unsuitable in the diagnoses of radiculopathy. CT myelography is the imaging modality of choice to visualize herniated discs in patients with contraindications for an MRI. However, due to its invasiveness, the assistance of a trained radiologist is required. Myelography is associated with risks like post-spinal headache, meningeal infection, and radiation exposure. Recent advances with a multidetector CT scan have made the diagnostic level of it nearly equal to the MRI.[12]

MRI: Is the gold standard study for confirming a suspected LDH. With a diagnostic accuracy of 97%, it is the most sensitive study to visualize a herniated disc due to its significant ability in soft tissue visualization. MRI also has higher inter-observer reliability than other imaging modalities. It suggests disc herniation when it shows an increased T2-weighted signal at the posterior 10% of the disc. Degenerative disc diseases have shown a correlation with Modic type 1 changes.[13] When evaluating for postoperative lumbar radiculopathies, the recommendation is that the MRI is performed with contrast unless otherwise contraindicated. MRI is more effective than CT in distinguishing inflammatory, malignant, or inflammatory etiologies of LDH. It is indicated relatively early in the course of evaluation (<8 weeks) when the patient presents with relative indications like significant pain, neurological motor deficits, and cauda equina syndrome. Diffusion tensor imaging is a type of MRI sequence used for detecting microstructural changes in the nerve root. It may be beneficial in understanding the changes that occur after herniated lumbar disc compresses a nerve root, and might help in differentiating the patients that need surgical intervention. In patients with a high suspicion of radiculopathy due to lumbar disc herniation, yet the MRI is equivocal or negative, nerve conduction studies are indicated.[1][5][8][9]

Treatment / Management

Most of the symptomatic presentations of LDH are short-lived and resolve within six to eight weeks; therefore, it is usually initially managed conservatively unless red flag symptoms are present, raising suspicion for emergent conditions such as progressive neurologic deficit or cauda equina syndrome. Conservative and surgical treatment have recently demonstrated equivalent outcomes in the medium and long term. However, other studies have shown an improved outcome in the surgically treated groups as it may result in faster relief of symptoms and improvement in the quality of life. There is no literature on an absolute non-operative versus operative criterion, yet there are relative indications for urgent surgical intervention in patients presenting with red flags. The ultimate decision regarding the treatment type of non-emergent LDH is based on the doctor-patient discussion in light of the evaluation, duration of symptoms, and patient’s wishes.[14]

Conservative Medical/Interventional Treatment

This approach is the initial management of choice in patients presenting with symptoms of acute lumbar disc herniation. Primary care practitioners can begin the treatment with a short course of rest if indicated, appropriate patient education, recommendations of physical exercises, and prescribing pain medications and physical therapy. In most cases, the symptoms will improve within a few weeks; thus, physical therapy is not recommended before three weeks of the onset of symptoms. Pain management could start with moderate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication; if unresponsive, opioids analgesics are the next step. However, the risks and side effects of opioids should be taken into consideration and discussed with the patient, and they should be prescribed for the shortest duration possible. If symptoms persist beyond six weeks, transforaminal or interlaminar epidural steroid injections may be considered for short term (2 to 4 weeks) pain relief in some patients with LDH and radiculopathy. It is recommended to use contrast-enhanced fluoroscopy to provide more accurate delivery of the epidural steroid injections. Medical and interventional treatment improves functional outcomes in most LDH with radiculopathy not warranting surgical intervention.[3][5][14]

Surgical Treatment

As always, surgical treatment is the final resort, yet discectomy and laminotomy performed to treat radiculopathy caused by LDH is still a commonly performed procedure with roughly 180,000 to 200,000 cases annually in the United States. Surgical intervention is the suggestion for patients with persistent disabling symptoms who do not respond to conservative and medical management. The decision to operate within six months to a year in a patient whose symptoms warrant a surgical intervention is associated with faster recovery and improved long-term outcomes.

There are several methods of performing the surgical intervention, including an open approach and a minimally invasive approach. The open approach is the open microsurgical discectomy. The minimally invasive approach in spinal surgery has seen increased utilization in the past two decades. It can be done with small incisions and tube access. It can divide into two main technologies, endoscopic and microsurgical. There are different approach strategies, whereby the surgical team chooses the approach based on the morphology and location of the herniated disc. When compared to open discectomy, minimally invasive procedures correlate with decreased operative time, less blood loss, and no difference in complications, reoperation rates, or wound infections. However, there is no difference in long-term patient-centered outcomes between open and minimally invasive surgeries.[14][15]

Total lumbar disc replacement has been used as an alternative to lumbar fusion for degenerative disc disease.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22] Its use for lumbar disc herniation has not caught on as it does not offer an advantage over the open approach or the minimally invasive approach.[23][24]

Differential Diagnosis

- Mechanical back pain

- Muscle strain

- Osteophytes

- Spondylolisthesis

- Degenerative spinal stenosis

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Epidural abscess

- Epidural hematoma

- Diabetic amyotrophy

- Metastasis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Synovial cyst

- Neurinoma

Prognosis

Symptomatic lumbar disc herniations are short-lived, and studies have shown that 85 to 90% of the cases will resolve within 6 to 12 weeks and without substantial medical intervention. However, if symptomatic for more than six weeks, patients are less likely to improve without intervention.[4][5] Patients without radiculopathy symptoms notice an improvement in even less time. This improvement is due to phagocytosis and enzymatic resorption of extruded material. Also, hydration of the extruded material or decrease in the local nerve edema might occur, which results in pain relief and restoration of function.

Factors predicting successful outcomes after surgery include severe preoperative leg and lower back pain, shorter symptoms duration, younger age, better mental health status, and increased preoperative physical activity.[1] Conservative medical treatment is equivalent to surgical interventions in the long term; however, the surgical interventions provide faster relief of pain-related symptoms and the possibility of earlier restoration of function.

Complications

Developing chronic back pain is one of the main complications of LDH. Furthermore, inadequate treatment can lead to lasting irreversible nerve damage and neuropathic pain in patients with severe nerve root compression. Complications associated with surgical interventions or epidural steroid injections are listed below.

Epidural steroid injections:

- Nerve injury

- Dural puncture, resulting in positional headache

- Infection

- Epidural abscess

- Epidural hematoma

- Paralysis (very rare)[25]

Surgical intervention:

- Worsening of functional status

- Dural tear

- Postoperative infection

- Nerve root injury

- Recurrent disc herniation

- Great vessels (aorta and vena cava) injury, secondary to perforation of the anterior longitudinal ligament

- Epidural fibrosis[26]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Over 85% of patients with acute herniated disc symptoms experience relief of symptoms within 6 to 12 weeks without any treatments, and those without radiculopathy symptoms notice an improvement in even less time.

The patient should be encouraged to obtain a rest period free of daily activities. For persistent pain, physical therapy should be consulted.

Patients who develop signs of cauda equina should seek emergent evaluation as prognosis and outcome will depend on the time to treatment from the initial symptoms.

Studies have shown that conservatory management and surgical treatment have similar outcomes after two years, although pain relief is faster with surgical treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Lumbar disc herniation frequently poses a diagnostic dilemma. Approximately 80 % of the population sustains an episode of low back pain in their lifetime. Patients with lumbar disc herniation may exhibit non-specific signs and symptoms such as low back pain and muscle spasm. While the physical exam may reveal that the patient may have a lumbar disc herniation, it is difficult to confirm without proper imaging studies.

While the primary care practitioner is almost always involved in the care of patients with a lumbar disc herniation, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include a pain specialist, a physiatrist, and a neurosurgeon. Collaboration, shared decision making, and communication are crucial elements for a favorable outcome. Physical therapists are essential to the initial management of patients with a lumbar disc herniation. The nurses are also vital members of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs and assist with the education of the patient and family.

In the postoperative period for pain and wound infection, the pharmacist will ensure that the patient is on the right analgesics and appropriate antibiotics. The radiologist also plays a vital role in determining the diagnosis. An interprofessional team that provides a holistic and integrated approach to preoperative and postoperative care can help achieve the best possible outcomes. The interprofessional care provided to the patient must use an integrated care pathway combined with an evidence-based approach to planning and evaluation of all joint activities.