[1]

Bagley C, MacAllister M, Dosselman L, Moreno J, Aoun SG, El Ahmadieh TY. Current concepts and recent advances in understanding and managing lumbar spine stenosis. F1000Research. 2019:8():. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-137. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16082.1. Epub 2019 Jan 31

[PubMed PMID: 30774933]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[2]

Ciol MA, Deyo RA, Howell E, Kreif S. An assessment of surgery for spinal stenosis: time trends, geographic variations, complications, and reoperations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996 Mar:44(3):285-90

[PubMed PMID: 8600197]

[4]

Zaina F, Tomkins-Lane C, Carragee E, Negrini S. Surgical Versus Nonsurgical Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Spine. 2016 Jul 15:41(14):E857-E868. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001635. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27128388]

[5]

Lee SH, Choi HH, Chang MC. The Effectiveness of Facet Joint Injection with Steroid and Botulinum Toxin in Severe Lumbar Central Spinal Stenosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Toxins. 2022 Dec 23:15(1):. doi: 10.3390/toxins15010011. Epub 2022 Dec 23

[PubMed PMID: 36668831]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[6]

Laiwalla AN, Ratnaparkhi A, Zarrin D, Cook K, Li I, Wilson B, Florence TJ, Yoo B, Salehi B, Gaonkar B, Beckett J, Macyszyn L. Lumbar Spinal Canal Segmentation in Cases with Lumbar Stenosis Using Deep-U-Net Ensembles. World neurosurgery. 2023 Oct:178():e135-e140. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.07.009. Epub 2023 Jul 10

[PubMed PMID: 37437805]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[7]

Kalichman L, Cole R, Kim DH, Li L, Suri P, Guermazi A, Hunter DJ. Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: the Framingham Study. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2009 Jul:9(7):545-50. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.03.005. Epub 2009 Apr 23

[PubMed PMID: 19398386]

[8]

Deer TR, Grider JS, Pope JE, Lamer TJ, Wahezi SE, Hagedorn JM, Falowski S, Tolba R, Shah JM, Strand N, Escobar A, Malinowski M, Bux A, Jassal N, Hah J, Weisbein J, Tomycz ND, Jameson J, Petersen EA, Sayed D. Best Practices for Minimally Invasive Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Treatment 2.0 (MIST): Consensus Guidance from the American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN). Journal of pain research. 2022:15():1325-1354. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S355285. Epub 2022 May 5

[PubMed PMID: 35546905]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Binder DK, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Seminars in neurology. 2002 Jun:22(2):157-66

[PubMed PMID: 12524561]

[10]

Yabuki S, Fukumori N, Takegami M, Onishi Y, Otani K, Sekiguchi M, Wakita T, Kikuchi S, Fukuhara S, Konno S. Prevalence of lumbar spinal stenosis, using the diagnostic support tool, and correlated factors in Japan: a population-based study. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 2013 Nov:18(6):893-900. doi: 10.1007/s00776-013-0455-5. Epub 2013 Aug 21

[PubMed PMID: 23963588]

[11]

Diwan S, Sayed D, Deer TR, Salomons A, Liang K. An Algorithmic Approach to Treating Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: An Evidenced-Based Approach. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2019 Dec 1:20(Suppl 2):S23-S31. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz133. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31808532]

[12]

Xu J, Si H, Zeng Y, Wu Y, Zhang S, Shen B. Transcriptome-wide association study reveals candidate causal genes for lumbar spinal stenosis. Bone & joint research. 2023 Jun 26:12(6):387-396. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.126.BJR-2022-0160.R1. Epub 2023 Jun 26

[PubMed PMID: 37356815]

[13]

Walter KL, O'Toole JE. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. JAMA. 2022 Jul 19:328(3):310. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6137. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 35503646]

[14]

Buser Z, Ortega B, D'Oro A, Pannell W, Cohen JR, Wang J, Golish R, Reed M, Wang JC. Spine Degenerative Conditions and Their Treatments: National Trends in the United States of America. Global spine journal. 2018 Feb:8(1):57-67. doi: 10.1177/2192568217696688. Epub 2017 Apr 7

[PubMed PMID: 29456916]

[15]

Abbas J, Yousef M, Peled N, Hershkovitz I, Hamoud K. Predictive factors for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: a model obtained from a machine learning algorithm technique. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2023 Mar 23:24(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06330-z. Epub 2023 Mar 23

[PubMed PMID: 36949452]

[16]

Wang S, Qu Y, Fang X, Ding Q, Zhao H, Yu X, Xu T, Lu R, Jing S, Liu C, Wu H, Liu Y. Decorin: a potential therapeutic candidate for ligamentum flavum hypertrophy by antagonizing TGF-β1. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2023 Jul:55(7):1413-1423. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01023-y. Epub 2023 Jul 3

[PubMed PMID: 37394592]

[17]

Yabe Y, Hagiwara Y, Tsuchiya M, Minowa T, Takemura T, Hattori S, Yoshida S, Onoki T, Ishikawa K. Comparative proteome analysis of the ligamentum flavum of patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. JOR spine. 2022 Dec:5(4):e1210. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1210. Epub 2022 Jun 9

[PubMed PMID: 36601375]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[18]

Jain M, Sable M, Tirpude AP, Sahu RN, Samanta SK, Das G. Histological difference in ligament flavum between degenerative lumbar canal stenosis and non-stenotic group: A prospective, comparative study. World journal of orthopedics. 2022 Sep 18:13(9):791-801. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v13.i9.791. Epub 2022 Sep 18

[PubMed PMID: 36189332]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[19]

Altun S, Alkan A, Altun İ. LSS-VGG16: Diagnosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis With Deep Learning. Clinical spine surgery. 2023 Jun 1:36(5):E180-E190. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001418. Epub 2023 Jan 20

[PubMed PMID: 36727890]

[20]

Jinkins JR. Gd-DTPA enhanced MR of the lumbar spinal canal in patients with claudication. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 1993 Jul-Aug:17(4):555-62

[PubMed PMID: 8331225]

[21]

Hall S, Bartleson JD, Onofrio BM, Baker HL Jr, Okazaki H, O'Duffy JD. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Clinical features, diagnostic procedures, and results of surgical treatment in 68 patients. Annals of internal medicine. 1985 Aug:103(2):271-5

[PubMed PMID: 3160275]

[22]

Ujigo S, Kamei N, Yamada K, Nakamae T, Imada H, Adachi N, Fujimoto Y. Balancing ability of patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2023 Dec:32(12):4174-4183. doi: 10.1007/s00586-023-07782-6. Epub 2023 May 22

[PubMed PMID: 37217822]

[23]

Munakomi S, Kumar BM. Wasting of Extensor Digitorum Brevis as a Decisive Preoperative Clinical Indicator of Lumbar Canal Stenosis: A Single-center Prospective Cohort Study. Annals of medical and health sciences research. 2016 Sep-Oct:6(5):296-300. doi: 10.4103/amhsr.amhsr_392_15. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28503347]

[24]

Katz JN, Dalgas M, Stucki G, Katz NP, Bayley J, Fossel AH, Chang LC, Lipson SJ. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and physical examination. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1995 Sep:38(9):1236-41

[PubMed PMID: 7575718]

[25]

Staartjes VE, Schröder ML. The five-repetition sit-to-stand test: evaluation of a simple and objective tool for the assessment of degenerative pathologies of the lumbar spine. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2018 Oct:29(4):380-387. doi: 10.3171/2018.2.SPINE171416. Epub 2018 Jun 29

[PubMed PMID: 29957147]

[26]

Oskouie IM, Rostami M, Moosavi M, Zarei M, Jouibari MF, Ataie H, Jafarieh A, Moghadam N, Kordi R, Khadivi M, Mazloumi A. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Persian version of selected PROMIS measures for use in lumbar canal stenosis patients. Journal of education and health promotion. 2023:12():99. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_668_22. Epub 2023 Mar 31

[PubMed PMID: 37288413]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[27]

Wang Y, Zhang P, Yan X, Wang J, Zhu M, Teng H. The correlation between lumbar interlaminar space size on plain radiograph and spinal stenosis. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2023 May:32(5):1721-1728. doi: 10.1007/s00586-023-07646-z. Epub 2023 Mar 20

[PubMed PMID: 36941496]

[29]

Pant YR, Paudel S, Lakhey RB, Pokharel RK. Nerve Root Sedimentation Sign among Lumbar Canal Stenosis Patients Visiting the Department of Orthopaedics in a Tertiary Care Centre: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA; journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2022 Dec 1:60(256):1030-1032. doi: 10.31729/jnma.7540. Epub 2022 Dec 1

[PubMed PMID: 36705116]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[30]

Ahn DY, Park HJ, Yi JW, Kim JN. To Assess Whether Lee's Grading System for Central Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Can Be Used as a Decision-Making Tool for Surgical Treatment. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe chi. 2022 Jan:83(1):102-111. doi: 10.3348/jksr.2021.0017. Epub 2021 Nov 4

[PubMed PMID: 36237366]

[31]

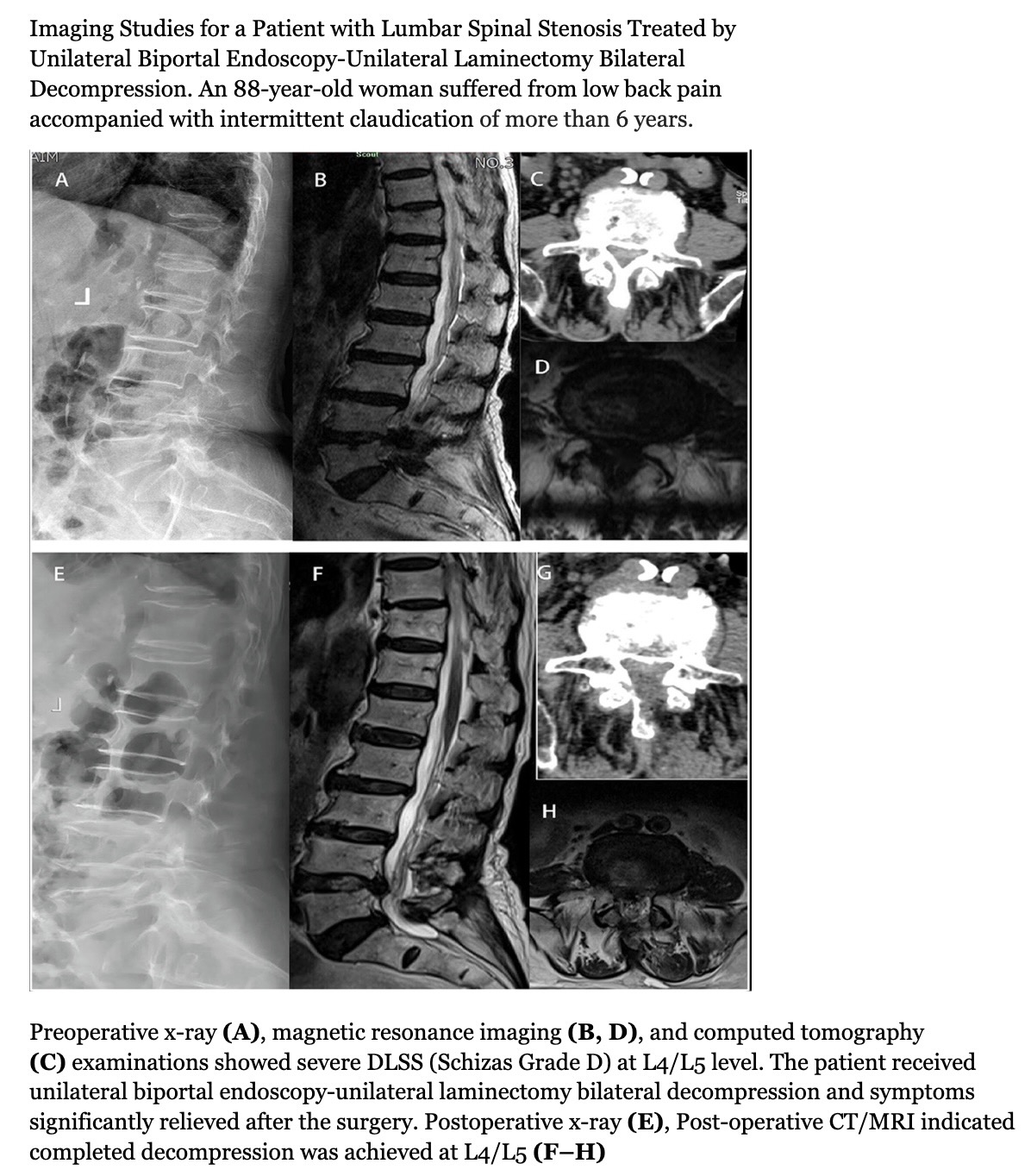

Ko YJ, Lee E, Lee JW, Park CY, Cho J, Kang Y, Ahn JM. Clinical validity of two different grading systems for lumbar central canal stenosis: Schizas and Lee classification systems. PloS one. 2020:15(5):e0233633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233633. Epub 2020 May 27

[PubMed PMID: 32459814]

[32]

Qian G, Wang Y, Huang J, Wang D, Miao C. Value of nerve root sedimentation sign in diagnosis and surgical indication of lumbar spinal stenosis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2023 Apr 28:24(1):336. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06459-x. Epub 2023 Apr 28

[PubMed PMID: 37118727]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[33]

Lee GY, Lee JW, Choi HS, Oh KJ, Kang HS. A new grading system of lumbar central canal stenosis on MRI: an easy and reliable method. Skeletal radiology. 2011 Aug:40(8):1033-9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1102-x. Epub 2011 Feb 1

[PubMed PMID: 21286714]

[34]

Fang X, Li J, Wang L, Liu L, Lv W, Tang Z, Gao D. Diagnostic value of a new axial loading MRI device in patients with suspected lumbar spinal stenosis. European radiology. 2023 May:33(5):3200-3210. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-09447-w. Epub 2023 Feb 23

[PubMed PMID: 36814030]

[35]

Bharadwaj UU, Christine M, Li S, Chou D, Pedoia V, Link TM, Chin CT, Majumdar S. Deep learning for automated, interpretable classification of lumbar spinal stenosis and facet arthropathy from axial MRI. European radiology. 2023 May:33(5):3435-3443. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-09483-6. Epub 2023 Mar 15

[PubMed PMID: 36920520]

[36]

Haig AJ, Tong HC, Yamakawa KS, Quint DJ, Hoff JT, Chiodo A, Miner JA, Choksi VR, Geisser ME. The sensitivity and specificity of electrodiagnostic testing for the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2005 Dec 1:30(23):2667-76

[PubMed PMID: 16319753]

[37]

Nüesch C, Mandelli F, Przybilla P, Schären S, Mündermann A, Netzer C. Kinematics and paraspinal muscle activation patterns during walking differ between patients with lumbar spinal stenosis and controls. Gait & posture. 2023 Jan:99():44-50. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.10.017. Epub 2022 Oct 26

[PubMed PMID: 36327537]

[38]

Bakewell BK, Sherman M, Binsfeld K, Ilyas AM, Stache SA, Sharma S, Stolzenberg D, Greis A. The Use of Cannabidiol in Patients With Low Back Pain Caused by Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: An Observational Study. Cureus. 2022 Sep:14(9):e29196. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29196. Epub 2022 Sep 15

[PubMed PMID: 36507111]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[39]

Mazanec DJ, Podichetty VK, Hsia A. Lumbar canal stenosis: start with nonsurgical therapy. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2002 Nov:69(11):909-17

[PubMed PMID: 12430977]

[40]

Fukusaki M, Kobayashi I, Hara T, Sumikawa K. Symptoms of spinal stenosis do not improve after epidural steroid injection. The Clinical journal of pain. 1998 Jun:14(2):148-51

[PubMed PMID: 9647457]

[41]

Rayegani SM, Soltani V, Cheraghi M, Omid Zohor MR, Babaei-Ghazani A, Raeissadat SA. Efficacy of ultrasound guided caudal epidural steroid injection with or without ozone in patients with lumbosacral canal stenosis; a randomized clinical controlled trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2023 Apr 29:24(1):339. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06451-5. Epub 2023 Apr 29

[PubMed PMID: 37120532]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[42]

Malmivaara A, Slätis P, Heliövaara M, Sainio P, Kinnunen H, Kankare J, Dalin-Hirvonen N, Seitsalo S, Herno A, Kortekangas P, Niinimäki T, Rönty H, Tallroth K, Turunen V, Knekt P, Härkänen T, Hurri H, Finnish Lumbar Spinal Research Group. Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis? A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007 Jan 1:32(1):1-8

[PubMed PMID: 17202885]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[43]

Süner HI, Castaño JP, Vargas-Jimenez A, Wagner R, Mazzei AS, Velazquez W, Jorquera M, Sallabanda K, Barcia Albacar JA, Carrascosa-Granada A. Comparison of the Tubular Approach and Uniportal Interlaminar Full-Endoscopic Approach in the Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Our 3-Year Results. World neurosurgery. 2023 May:173():e148-e155. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.02.022. Epub 2023 Feb 10

[PubMed PMID: 36775236]

[44]

Zhang Y, Feng B, Su W, Liu D, Hu P, Lu H, Geng X. [Early-effectiveness of unilateral biportal endoscopic laminectomy in treatment of two-level lumbar spinal stenosis]. Zhongguo xiu fu chong jian wai ke za zhi = Zhongguo xiufu chongjian waike zazhi = Chinese journal of reparative and reconstructive surgery. 2023 Jun 15:37(6):706-712. doi: 10.7507/1002-1892.202302014. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 37331947]

[45]

Hu YT, Fu H, Yang DF, Wang X, Xu WB. [Comparative study of decompression of unilateral biportal endoscopic compared to laminectomy with fusion and internal fixation in the treatment of severe lumbar spinal stenosis]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2022 Nov 8:102(41):3281-3287. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20220720-01583. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 36319180]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[46]

Lin GX, Yao ZK, Xin C, Kim JS, Chen CM, Hu BS. A meta-analysis of clinical effects of microscopic unilateral laminectomy bilateral decompression (ULBD) versus biportal endoscopic ULBD for lumbar canal stenosis. Frontiers in surgery. 2022:9():1002100. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1002100. Epub 2022 Sep 23

[PubMed PMID: 36211279]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[47]

Patel K, Harikar MM, Venkataram T, Chavda V, Montemurro N, Assefi M, Hussain N, Yamamoto V, Kateb B, Lewandrowski KU, Umana GE. Is Minimally Invasive Spinal Surgery Superior to Endoscopic Spine Surgery in Postoperative Radiologic Outcomes of Lumbar Spine Degenerative Disease? A Systematic Review. Journal of neurological surgery. Part A, Central European neurosurgery. 2024 Mar:85(2):182-191. doi: 10.1055/a-2029-2694. Epub 2023 Feb 6

[PubMed PMID: 36746397]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[48]

Junjie L, Jiheng Y, Jun L, Haixiong L, Haifeng Y. Comparison of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy Decompression and Microscopic Decompression Effectiveness in Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Asian spine journal. 2023 Apr:17(2):418-430. doi: 10.31616/asj.2021.0527. Epub 2023 Feb 6

[PubMed PMID: 36740930]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[49]

Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Yoo RI, Harris IA, Pinheiro MB, Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Rzewuska M, Maher CG, Ferreira ML. Surgical options for lumbar spinal stenosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Nov 1:11(11):CD012421

[PubMed PMID: 27801521]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[50]

Gupta S, Bansal T, Kashyap A, Sural S. Correlation between clinical scoring systems and quantitative MRI parameters in degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2022 Dec:35():102050. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2022.102050. Epub 2022 Oct 20

[PubMed PMID: 36317084]

[51]

Inose H, Kato T, Matsukura Y, Hirai T, Yoshii T, Kawabata S, Takahashi K, Okawa A. Factors influencing the long-term outcomes of instrumentation surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: a post-hoc analysis of a prospective randomized study. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2023 Jun:23(6):799-804. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2023.02.002. Epub 2023 Feb 11

[PubMed PMID: 36774998]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[52]

Yeung CM, Heard JC, Lee Y, Lambrechts MJ, Somers S, Singh A, Bloom E, D'Antonio ND, Trenchfield D, Labarbiera A, Mangan JJ, Canseco JA, Woods BI, Kurd MF, Kaye ID, Lee JK, Hilibrand AS, Vaccaro AR, Kepler CK, Schroeder GD. The Implication of Preoperative Central Stenosis on Patient-Reported Outcomes After Lumbar Decompression Surgery. World neurosurgery. 2023 Jun 19:():. pii: S1878-8750(23)00806-9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.06.038. Epub 2023 Jun 19

[PubMed PMID: 37343674]

[53]

Nagai S, Inagaki R, Michikawa T, Kawabata S, Ito K, Hachiya K, Takeda H, Ikeda D, Kaneko S, Yamada S, Fujita N. Efficacy of surgical treatment on polypharmacy of elderly patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis: retrospective exploratory research. BMC geriatrics. 2023 Mar 24:23(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-03853-x. Epub 2023 Mar 24

[PubMed PMID: 36964497]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[54]

Imai T, Nagai S, Michikawa T, Inagaki R, Kawabata S, Ito K, Hachiya K, Takeda H, Ikeda D, Yamada S, Fujita N, Kaneko S. Impact of Lumbar Surgery on Pharmacological Treatment for Patients with Lumbar Spinal Canal Stenosis: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Mar 20:12(6):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12062385. Epub 2023 Mar 20

[PubMed PMID: 36983385]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[55]

Yokoyama K, Ikeda N, Tanaka H, Ito Y, Sugie A, Yamada M, Wanibuchi M, Kawanishi M. Long-Term Changes in Sagittal Balance After Microsurgical Decompression of Lumbar Spinal Canal Stenosis in Elderly Patients: A Follow-Up Study for 5-Years After Surgery. World neurosurgery. 2023 Aug:176():e384-e390. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.05.069. Epub 2023 May 24

[PubMed PMID: 37236312]

[56]

D'Antonio ND, Lambrechts MJ, Trenchfield D, Sherman M, Karamian BA, Fredericks DJ, Boere P, Siegel N, Tran K, Canseco JA, Kaye ID, Rihn J, Woods BI, Hilibrand AS, Kepler CK, Vaccaro AR, Schroeder GD. Patient-specific Risk Factors Increase Episode of Care Costs After Lumbar Decompression. Clinical spine surgery. 2023 Oct 1:36(8):E339-E344. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001460. Epub 2023 Mar 30

[PubMed PMID: 37012618]

[57]

Murata S, Nagata K, Iwasaki H, Hashizume H, Yukawa Y, Minamide A, Nakagawa Y, Tsutsui S, Takami M, Taiji R, Kozaki T, J Schoenfeld A, K Simpson A, Yoshida M, Yamada H. Long-Term Outcomes after Selective Microendoscopic Laminotomy for Multilevel Lumbar Spinal Stenosis with and without Remaining Radiographic Stenosis: A 10-Year Follow-Up Study. Spine surgery and related research. 2022 Sep 27:6(5):488-496. doi: 10.22603/ssrr.2021-0200. Epub 2022 Feb 10

[PubMed PMID: 36348688]

[58]

Varol E, Etli MU, Avci F, Yaltirik CK, Ramazanoglu AF, Onen MR, Naderi S. Comparison of clinical and radiological results of dynamic and rigid instrumentation in degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Journal of craniovertebral junction & spine. 2022 Jul-Sep:13(3):350-356. doi: 10.4103/jcvjs.jcvjs_63_22. Epub 2022 Sep 14

[PubMed PMID: 36263334]

[59]

Aghajanloo M, Abdoli A, Poorolajal J, Abdolmaleki S. Comparison of clinical outcome of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery in patients with and without osteoporosis: a prospective cohort study. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2023 Jun 21:18(1):443. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-03935-x. Epub 2023 Jun 21

[PubMed PMID: 37344883]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[60]

Lu C, Qiu H, Huang X, Yang X, Liu D, Zhang S, Zhang Y. Meta-Analysis of Simultaneous versus Staged Decompression of Stenotic Regions in Patients with Tandem Spinal Stenosis. World neurosurgery. 2023 Feb:170():e441-e454. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.11.028. Epub 2022 Nov 14

[PubMed PMID: 36396060]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[62]

Shaygan M, Zamani M, Jaberi A, Eghbal K, Dehghani A. The impact of physical and psychological pain management training on pain intensity, anxiety and disability in patients undergoing lumbar surgeries. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2023 May:23(5):656-664. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2023.01.016. Epub 2023 Feb 1

[PubMed PMID: 36736739]

[63]

Gatam AR, Gatam L, Phedy, Mahadhipta H, Ajiantoro, Aprilya D. Full Endoscopic Lumbar Stenosis Decompression: A Future Gold Standard in Managing Degenerative Lumbar Canal Stenosis. International journal of spine surgery. 2022 Sep:16(5):821-830. doi: 10.14444/8338. Epub 2022 Sep 28

[PubMed PMID: 36171020]