Continuing Education Activity

The area between the lumbar vertebral bodies and sacral vertebral bodies is a transition zone at increased risk of injury due to the change in biomechanics that occurs between these regions. Separating each vertebral body of the spine are pads of fibrocartilage-based structures that provide support, flexibility, and minor load sharing known as the intervertebral discs. These are primarily composed of two layers, a soft, pulpy nucleus pulposus on the inside of the disc and a surrounding firm structure known as the annulus fibrosus. An injury to the normal architecture of the disc's annulus fibrosus can lead to degeneration or a protrusion of the inner nucleus pulposus, possibly applying pressure to the spinal cord or nerve root resulting in pain and weakness. This activity reviews the etiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of lumbosacral disc injuries and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating, diagnosing, and managing the condition.

Objectives:

- Describe various lumbar discopathies and their accompanying pathophysiology.

- Review the necessary elements for an examination to assess for lumbar discopathy, including necessary imaging studies.

- Summarize the treatment options available for lumbar disc injuries, including both conservative and surgical care.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the management of lumbosacral discopathies and improve outcomes.

Introduction

The area between the lumbar vertebral bodies and sacral vertebral bodies is a transition zone at increased risk of injury due to the change in biomechanics that occurs between these regions. Separating each vertebral body of the spine are pads of fibrocartilage-based structures that provide support, flexibility, and minor load sharing known as the intervertebral discs. These are primarily composed of two layers, a soft, pulpy nucleus pulposus on the inside of the disc and a surrounding firm structure known as the annulus fibrosus.[1][2][3] An injury to the normal architecture of the disc's annulus fibrosus can lead to degeneration or a protrusion of the inner nucleus pulposus, possibly applying pressure to the spinal cord or nerve root resulting in pain and weakness.

Slightly more than 90% of herniated discs occur at the L4-L5 or the L5-S1 disc space. If the disc injury progresses to the point of neurologic compromise or limitations with activities of daily living, then surgical intervention may be required to decompress and stabilize the affected segments. A non-operative course of analgesia, activity modification and injections should be tried for several months in the absence of motor deficits.[4]

Etiology

Interestingly, while a common belief is that repetitive forward flexion actions correlate with a disc injury, no studies correlate to a dose-response relationship between physical loading and disc injury. It is now thought that the literature on intervertebral disc disease once associated with these heavy physical loading in occupations may be confounded by correlations with a lower socioeconomic status or lifestyle factors seen in this cohort.[5]

Recent research has shown that there is a very significant genetic component to disc injuries and degeneration of the spine. Supporting studies of monozygotic twins with disc injuries support the importance of genetic predispositions. For example, in a study of the MRIs of 115 monozygotic twins, 34% of the variability in disc degeneration could be explained by genetics (versus 2% for the physical loading, 7% for age) at the L4-S1 region.

Epidemiology

The true incidence and accepted definition of a disc injury have changed with the increased availability of MRI. Most intervertebral disc degenerations are asymptomatic, resulting in difficulty determining the true prevalence. Additionally, due to the lack of uniformity in the definitions of disc degenerations and disc herniations, the actual prevalence of the disease is difficult to review across multiple studies.[6] In a meta-analysis of 20 studies evaluating the MRI of asymptotic individuals, the reported prevalence of disc abnormalities at any level were: 20% to 83% for a reduction in signal intensity, 10% to 81% for disc bulges, 3% to 63% for disc protrusion (versus 0% to 24% for disc extrusion), 3% to 56% for disc narrowing, and 6% to 56% with annular tears. This study supports that the mere incidental finding of disc disease is common and should not necessitate specialist evaluation in the absence of pain or limitations.

Pathophysiology

The radiation of back pain associated with disc disease is thought to be due to compression of the nerve roots in the spinal canal from a disc bulge or expansion of degenerative tissues (i.e., ligamentum flavum, facet joints). In a 2010 study by Suri et al. of 154 consecutive patients presenting with new lumbar disk herniation, 62% noted the symptoms began spontaneously compared to just 26% reporting the symptoms started after a specific household task or seemingly common non-lifting activity. Contrary to popular belief, fewer than 8% reported this acute sciatica started after heavy lifting or physical trauma.

Histopathology

The many tiny blood vessels that surround the spinal cord and nerve roots are paramount to delivering nutrition, oxygen, and chemomodulators. Compression of these structures limits the ability of these vessels to deliver vital nutrients, resulting in an ischemic effect of the structure. The subsequent inflammation from their compression results in (ischemic) pain along the path of this nerve root. This compression causes an increase in cytokines, TNF-alpha, and the recruitment of macrophages.

History and Physical

Obtaining a history from the patient should focus on the onset of pain, presence or absence of radicular symptoms, and any inciting injuries or traumas. The clinician should thoroughly investigate the presence (or absence) of the following clinical parameters:

- Postural-specific influences on back pain/symptoms (e.g., flexing forward, lying supine)

- Quantify ability to ambulate without symptoms

- History of prior symptoms, injuries, or surgeries

- Presence of weakness and/or numbness/tingling

- Systemic symptoms, illnesses, unintentional weight loss, or recent travel locations

Radiating pain as the main issue has a much more predictable surgical outcome compared to a presentation of non-specific lower back pain that likely is related to muscle fatigue and strain. A mechanical component to the back pain (i.e., the pain only with certain movements) may indicate instability or a degenerative fracture of the pars at L5.

Evaluating the patient’s gait is critical to understand better the daily impact this pain/deficit is causing. Having the patient arise from the chair, walk on his or her heels and toes, and then sit on the examination table for testing of strength, reflex, and straight leg testing is one systematic order. All physical examinations will include an evaluation of the neurologic function of the arms, legs, bladder, and bowels. The keys to a thorough exam are organization and patience. One should evaluate not only strength but also sensation and reflexes. It is also important to inspect the skin along the back and document the presence of tenderness to compression or any prior surgical scars. The straight leg test consists of a supine patient having his/her fully extended leg passive stretched from 0 to about 80. The onset of radiating back pain in either leg supports a diagnosis of a stenotic canal.

A disc herniation at the L5/S1 level can have two overlapping presentations:

- L5 at the L5/S1 level, a disc herniation far laterally into the left/right neural foramen would compress the L5 nerve, resulting in weakness of hip abduction muscles, ankle dorsiflexion (anterior tibialis muscle), and/or extension of the great toe (extensor hallucis longus muscle).

- S1 at the L5/S1 level, a disc herniation centrally into the canal would compress the S1 nerve, resulting in weakness of ankle plantar flexion (gastrocnemius muscle).

Evaluation

Specific clinical tests may also be useful for the diagnosis of lumbosacral disc injury. In a 2011 study by Suri et al., it was found that a combination of positive findings for the straight leg test and Achilles reflex test had a sensitivity of 79% for low lumbar nerve root impingement. They also reported how a positive straight leg test finding could be supplemented with a contralateral positive straight leg test, increasing the specificity (84% versus 96%) for lower lumbar disc herniations.[7][8][9]

Evaluation of patients with low back typically includes anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the affected region of the spine. In addition, the evaluation of suspected lumbosacral disc injuries with associated “red-flags,” should result in an MRI for possible surgical planning. Examples of these red flags include:

- Cauda equina syndrome (issues controlling bowel/bladder; difficulty starting urination)

- Infection (high suspicion in intravenous (IV) drug user; history of fever; nighttime chills)

- Tumor suspected (Known history of cancer; new-onset weight loss)

- Trauma (fall; assault; collision)

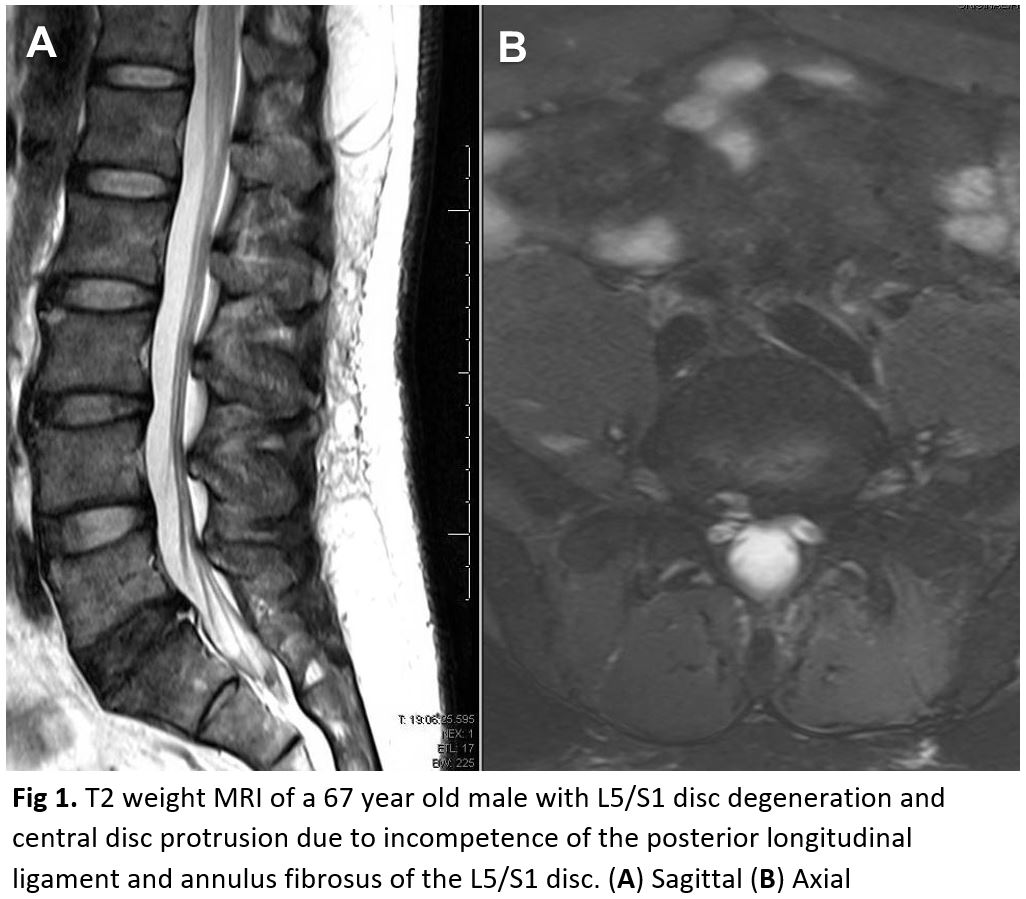

It is worth noting that most patients presenting with classic symptoms consistent with an acute paraspinal or low lumbar muscle strain do not need radiographic imaging. Persistent imaging or concerning examination findings can first begin with the aforementioned radiographs, with the possible addition of flexion/extension radiographs if segmental instability and/or spondylolisthesis are suspected. An MRI should not be ordered at initial presentations of suspected acute disc herniations in patients lacking “red flags.” These patients will initially trail a six-week course of physical therapy and frequently improve, an MRI likely is an unnecessary financial and utilization burden in the initial presentation. If at follow-up the symptomology is still present, then an MRI can be obtained at that time. The focus should be directed to the T2 weighted sagittal and axial images as these will illustrate any compression of neurologic elements (Figure 1).

Over time, both symptomatic and asymptomatic disc herniations will decrease in size on MRI. The finding of disc disease (degeneration or herniation) on MRI does not correlate with the likelihood of chronic pain or future need for surgery.

Treatment / Management

Fortunately, more than 90% of patients with L5/S1 disc injuries will improve without surgical treatment. Conservative management includes six weeks of physical therapy with an emphasis on core strengthening and stretching. Additional non-surgical intervention includes- modification of the activity that may exacerbate the pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), and epidural injections. Epidural injections may provide moderate/short-term relief for lumbosacral-related pain due to disc herniations, but the literature regarding the usefulness of injections for chronic non-radiating back pain is less certain. Injections can also be targeted at the facet of L5/S1 if MRI-T2 correlates with this site being an area of increased inflammation.[10][11][3]

With a failed conservative course the patient has three options- continued pain, complete avoidance of activities that elicit pain, or surgical intervention. One of the most cited guides on the outcomes of surgical versus conservative management for lumbar disc herniations comes from the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). In their report, patients electing for surgery had better outcomes at three months, two years, and four years compared to the non-surgery patients. The literature regarding the optimal surgical procedure, approach, and roles for decompression/instrumentation continues to expand. Currently, the literature shows that traditional open surgery compared to microdiscectomy are both broadly similar and effective. In regards to the amount of disc removed during a discectomy, while a “limited” discectomy provides better pain relief and patient satisfaction compared to a subtotal discectomy, they have a higher risk of repeat herniations. Interestingly, patient outcomes and satisfaction are similar in repeat/revision micro discectomies as compared to their initial discectomy. The operation at times requires overnight hospitalization, but frequently these are designed to be outpatient procedures. It is important for the patient to understand that while surgical intervention has favorable outcomes for relieving radicular pains, the results are less predictable for non-radiating lower back pain.

Differential Diagnosis

- Abdominal pain in elderly persons

- Acute aortic dissection

- Cauda equina

- Constipation

- Epidural infections

- Herpes zoster

- Mechanical back pain

- Nephrolithiasis

- Osteomyelitis

- Sickle cell anemia

Pearls and Other Issues

The most common cause of lower back pain is not disc injury but is instead muscle strain and muscle fatigue. Modifiable factors that contribute to chronic low back pain include poor ergonomic posture, obesity, and weak core muscles. Some of these structures include the abdominal muscles, thoracic spinal erector muscles, multifidus muscles, and oblique muscles. In addition, muscular and ligamentous support around the vertebral column can help offset axial loads and potentially lessen the impacts associated with disc injuries.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Most patients with lumbosacral disc injury will present to the emergency department, primary care provider, or nurse practitioner. While most patients can be managed with conservative care, it is important to refer patients with neurological deficits to the orthopedic surgeon. The primary care providers should educate these patients on preventing lumbosacral pain by lowering body weight, exercising regularly, and avoiding tobacco. Unfortunately, patient compliance is poor, and relapse of low back pain is very common. Surgery only helps a select few but is also associated with serious complications that can result in permanent disability.[12][13][14] [Level V]