Introduction

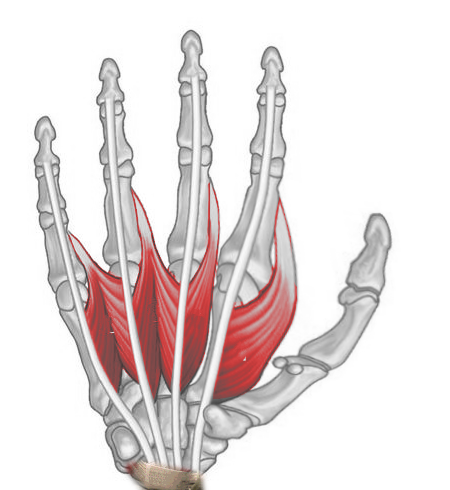

The lumbrical muscles comprise a set of 4 intrinsic hand muscles attached to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendons proximally and the digits' extensor expansions distally (see Image. Right Hand Lumbricals, Anterior View). These muscles are cylindrical and wormlike, resembling earthworms belonging to the genus Lumbricus. All 4 lumbricals flex the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints and extend the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.[1]

By coordinating with other hand muscles, the lumbricals help control the fine and delicate movements of the fingers. The actions of these muscles are essential for gripping objects, typing, and performing various dexterous hand movements. This is a review of the anatomy and clinical importance of the lumbricals.

Structure and Function

The lateral 2 lumbricals are unipennate muscles. The 1st lumbrical originates from the lateral side of the 1st FDP tendon and inserts on the extensor hood of the 2nd digit. The 2nd lumbrical originates on the lateral side of the 2nd FDP tendon and inserts on the extensor hood of the 3rd digit.

The medial 2 lumbricals are bipennate muscles. One head of the 3rd lumbrical originates from the medial portion of the 2nd FDP tendon, while the other originates from the lateral portion of the 3rd FDP tendon. Distally, the 3rd lumbrical inserts on the extensor hood of the 4th digit.

Meanwhile, the lateral head of the 4th lumbrical originates from the lateral surface of the 4th FDP tendon, while the medial head of the 4th lumbrical originates from the lateral portion of the 4th FDP tendon. The distal attachment site of the 4th lumbrical is the extensor hood of the 5th digit.[1]

Although the lumbricals arise from the FDP tendons, these muscles partially antagonize each other's actions. The lumbricals flex the MCP joints and extend the PIP and DIP joints. In contrast, the FDP flexes all 3—the MCP, PIP, and DIP joints. The lumbricals' tendons pass anteriorly to the deep transverse metacarpal ligaments.

Embryology

After the 4th week of embryonic development, 4 limb buds arise from the somites and mesenchyme of the lateral plate mesoderm, which is covered by a layer of ectoderm. Protein factors, particularly fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and sonic hedgehog (SHH) protein, induce upper limb development in the proximodistal, anteroposterior, and dorsoventral axes.[2]

Hand development begins with flattening of the distal upper extremity buds around days 34 to 38 of embryonic development. The somites form the limb musculature, while the mesenchyme of the lateral plate mesoderm forms bone and cartilage. The somitic mesoderm of the hand divides into superficial and deep layers, with the superficial muscles developing earlier than the deep muscles. The lumbrical muscles originate from the deep mesodermal layer. Lumbrical tendons are fully developed and functional by the 12th week of development.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lumbricals' arterial circulation arises from 4 different vessels, the most important of which is the superficial palmar arch. Other arteries contributing to the anastomotic network in this region are the deep palmar arch, dorsal digital arteries, and palmar digital arteries. The corresponding veins accompany these arteries, draining into the cephalic vein on the hand's lateral side and basilic vein on the medial aspect.[4]

Upper limb lymphatic drainage divides into superficial and deep lymphatic drainage. Palmar and dorsal lymphatic plexuses ascend with the cephalic and basilic veins towards the axillary and cubital lymph nodes, respectively. The deep lymphatic vessels follow the primary deep veins and eventually terminate in the humeral lymph nodes.

Nerves

The digital branches of the median nerve innervate the 1st and 2nd lumbricals. The 3rd and 4th lumbricals are supplied by the deep branch of the ulnar nerve. Injuries to these nerves manifest as motor and sensory deficits in different parts of the hand.[5]

Muscles

The lumbrical muscles are located deep in the palm. These muscles originate from the FDP tendons and insert on the fingers' extensor expansions, which are connected to the proximal and middle phalanges. Each finger attaches to 2 lumbricals, except for the thumb, which is associated only with the 1st lumbrical muscle.

The lumbricals are essential for the fingers' precision grip and fine motor control. These muscles flex the MCP joints and extend the PIP and DIP joints, coordinating with other hand muscles.

Physiologic Variants

The most common innervation pattern of the lumbricals has the median nerve supplying the lateral 2 lumbricals and the ulnar nerve innervating the medial 2 lumbricals. This pattern has a prevalence of 50-60%. Meanwhile, 20-30% of individuals have the median nerve innervating only the 1st lumbrical, while the rest have the median nerve innervating the lateral 3 lumbricals.

One cadaveric study revealed a variant where the 3rd lumbrical possessed dual innervation from both the median and ulnar nerves.[5] While innervation to the middle lumbricals can vary, most agree that the median nerve always supplies the 1st lumbrical and the 4th lumbrical is always innervated by the deep branch of the ulnar nerve.[6]

The lumbricals' structure and arrangement also differ among different people. A double 1st lumbrical, a bipennate 2nd lumbrical, and an absent 3rd lumbrical have been reported previously.

Distal lumbrical insertion sites also have variations, with variability increasing from the lateral to the medial lumbricals. Insertions on the proximal phalanx, volar aspect of the MCP joint, extensor hood, and combinations of these have been reported.[7] Additional insertions on the extensor hood are most common in the 1st lumbrical, and attachments to bone and the volar plate are most common in the 4th lumbrical.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Lumbrical flaps have been used to correct median nerve conditions, such as carpal tunnel syndrome and neuromas in continuity. One case study reported using this technique, with the 1st lumbrical covering the exposed median nerve. The patient had a hand infection, but soft tissue reconstruction could not be performed due to the acuity of the inflammation in the setting of diabetes.

The same study reported the same technique being used on a patient whose right median nerve was compressed by extensive scarring. The authors used the 2nd lumbrical to cover the median nerve and buffer it from the overlying scar tissue. Complete symptom resolution was observed 18 months later.

Another study reported using lumbrical flaps to cover areas where neuromas were subjected to neurolysis. All patients who received this treatment were relieved of pain and did not experience hand function impairment.[9]

Clinical Significance

Aberrant lumbrical anatomy, eg, when the muscle originates proximally, can cause median nerve compression.[10][11][12] Moreover, carpal tunnel syndrome can result from lumbrical muscle hypertrophy, which can occur if the muscle has an anomalous origin and is prone to being overused.[13]

Ulnar nerve entrapment ranks as the second most common compression neuropathy. This condition typically arises from nerve root impingement, brachial plexus compression, or nerve entrapment at the elbow, forearm, or wrist. Ulnar nerve damage weakens the medial 2 lumbricals, sparing their lateral counterparts, which are supplied by the median nerve.[14]

A clinician can assess lumbrical muscle strength by asking the patient to flex the MCP joints with the palm supine and the interphalangeal (IP) joints extended. The clinician then applies a counterforce along the palmar surface of the proximal phalanx of digits 2 to 5 individually. Resistance may also be applied on the dorsal surfaces of the middle and distal phalanges of digits 2 to 5, which tests IP joint extension while maintaining MCP joint flexion.