Introduction

The mandible is the largest bone in the human skull, forming the lower jawline and shaping the contour of the inferior third of the face.[1] Articulation with the skull base at the bilateral temporomandibular joints allows a range of movements facilitated by associated muscles, including dental occlusion with the maxilla. The mandible is also the insertion point for a range of muscles involved in facial expression. Mandible fractures are relatively common in trauma, particularly among young males, and half are caused by interpersonal violence.[2]

Structure and Function

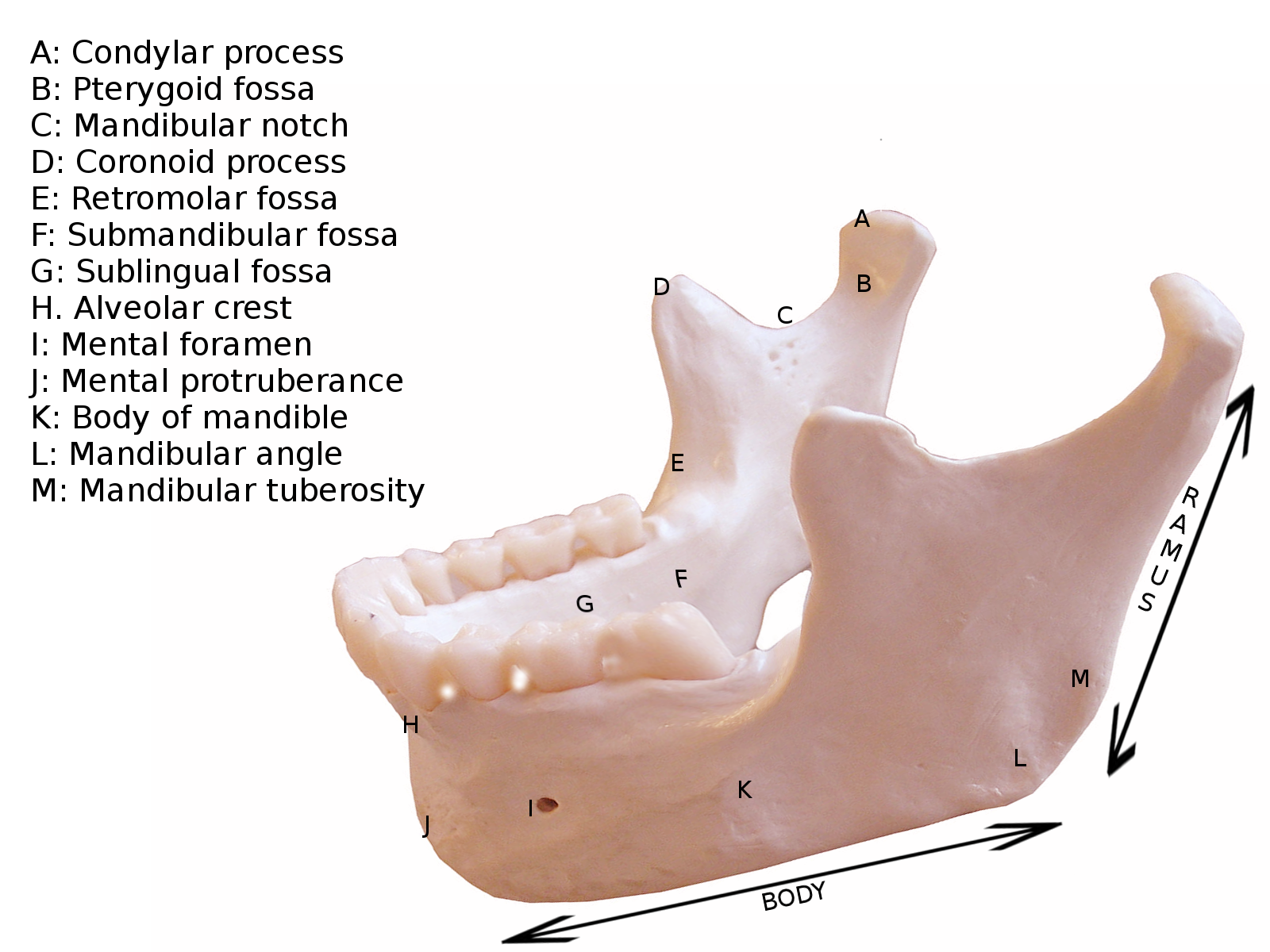

The mandible is made up of a U-shaped body that projects anteroposteriorly. At the posterior ends of the body are the bilateral gonial angles, from which the rami extend vertically towards the articulation with the cranial base.[3]

Body

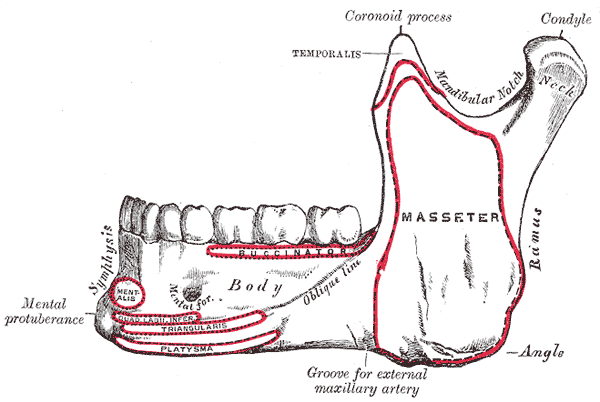

The body of the mandible is the horizontal U-shaped portion of the mandible. The mandibular symphysis is found anteriorly in the midline, where the two constituent fetal bones fuse after birth.[4] This is palpable as a small vertical ridge in the adult, which inferiorly splits to enclose a midline depression termed the mental protuberance, the edges of which are the mental tubercles. From the mental tubercles, the external oblique line runs posteriorly to the anterior border on the ramus.

The superior surface of the mandibular body consists of alveolar bone, is lined with tooth sockets, and is covered with mucoperiosteum, which forms the gingivae.

The bilateral mental foramina are an important landmark on the external mandibular surface, as it allows access to the mental nerve for a local anesthetic block. This landmark lies halfway between the upper and lower borders of the mandibular body, most commonly on the imaginary line which would run between the first and second premolars, although this varies with age.[5]

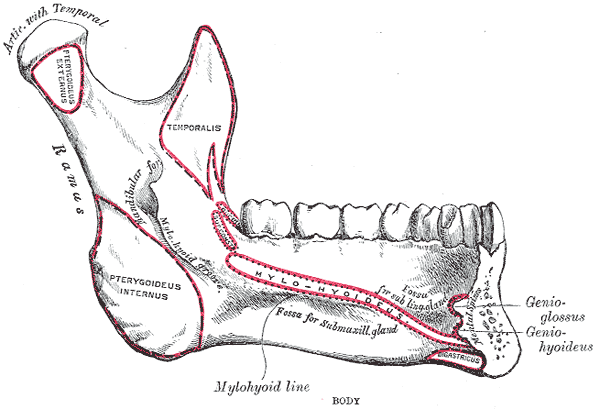

The internal surface of the body is crossed obliquely by the mylohyoid line that starts from just below the posterior border of the third molar and runs anteroinferiorly to fade into the midline.[6] Below the middle part of the mylohyoid line lies the smooth submandibular fossa, which contains part of the submandibular gland. Further anteriorly, close to the midline, the sublingual fossa lies above the mylohyoid line and contains the sublingual gland.

In the midline of the internal surface of the mandibular body are four mental spines, which serve as attachments for intrinsic tongue muscles.[7] Finally, two rounded depressions termed the digastric fossae can be found just laterally to the midline, where the anterior bellies of the digastric muscle attach.

Ramus

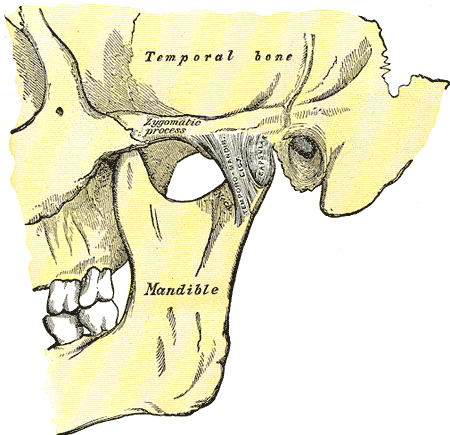

The ramus contributes to the lateral portion of the mandible on either side. The anterior border of the ramus terminates superiorly as the coronoid process and the posterior border as the condyle or head of the mandible. The smooth concave mandibular notch separates the two. The condyle of the mandible contributes to the temporomandibular joint, with a biconcave fibrocartilaginous disc intervening between the condyle and the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone.[8]

The lateral surface of the ramus contains a portion of the oblique line, which begins on the external surface of the body inferiorly. This surface also provides the origin for the masseter muscle.

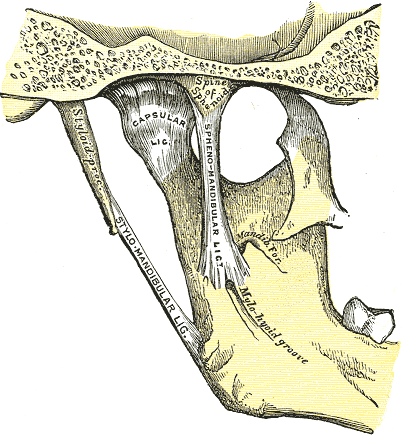

The internal surface of the ramus is punctured by the mandibular foramen, situated halfway between the anterior and posterior borders of the ramus at the level of the occlusal surfaces of the lower teeth, and through which the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels enter the mandibular canal, ultimately terminating at the mental foramen.[9] The lingula is a small flap of bone that overlies the anterior part of the mandibular foramen, to which the sphenomandibular ligament attaches.[10] The mylohyoid groove is an inferior continuation from the lingula, through which the mylohyoid nerve and vessels travel after piercing the sphenomandibular ligament.

The coronoid process is located at the superior aspect of the ramus. Its anterior border is continuous with that of the ramus, and its posterior border creates the anterior boundary of the mandibular notch. The temporalis muscle and masseter insert on its lateral surface.

The condyloid process is also located at the superior aspect of the ramus and is divided into two parts, the neck and the condyle. The neck is the thinner portion of the condyloid process that projects from the ramus. The condyle is the most superior portion and contributes to the temporomandibular junction by articulating with the articular disk.[8]

Embryology

During the sixth week of intrauterine development, the mandible is the second bone to ossify, following the clavicle.[11] The first pharyngeal arch, the mandibular arch, gives rise to the Meckel cartilage. This cartilage serves as a template for the development of the mandible. A fibrous membrane covers the left and right Meckel cartilage at their ventral ends, each of which gives rise to a single ossification center. These two halves eventually fuse via fibrocartilage at the mandibular symphysis. Thus, the mandible is still composed of two separate bones at birth. Ossification and fusion of the mandibular symphysis occur during the first year of life, resulting in a single bone. The remnant of the mandibular symphysis is a subtle ridge at the midline of the mandible.[11]

The mandible constantly changes throughout life. At birth, the gonial angle is approximately 160 degrees. By age four, teeth have formed, causing the jaw to elongate and widen; these changes in the mandible's dimensions cause the gonial angle to decrease to approximately 140 degrees. By adulthood, the gonial angle is reduced to approximately 120 degrees.[11]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the mandible is via small periosteal and endosteal vessels. The periosteal vessels arise mainly from the inferior alveolar artery and supply the ramus of the mandible. The endosteal vessels arise from the peri-mandibular branches of the maxillary artery, facial artery, external carotid artery, and superficial temporal artery; these supply the body of the mandible.[12] Dental branches from the inferior alveolar artery supply the mandibular teeth.

Lymphatic drainage of the mandible and mandibular teeth is primarily via the submandibular lymph nodes. However, the mandibular symphysis region drains into the submental lymph node, which subsequently drains into the submandibular nodes.

Nerves

The main nerve associated with the mandible is the inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The inferior alveolar nerve enters the mandibular foramen and courses anteriorly in the mandibular canal, sending branches to the lower teeth and providing sensation. At the mental foramen, the inferior alveolar nerve branches into the incisive and mental nerve. The mental nerve exits the mental foramen and courses superiorly to provide sensation to the lower lip. The incisive nerve runs in the incisive canal, providing innervation to the mandibular premolar, canine, and lateral and central incisors.[13]

Muscles

Muscles Originating from the Mandible

- Mentalis - originates from the incisive fossa

- Orbicularis oris - originates from the incisive fossa

- Depressor labii inferioris - originates from the oblique line

- Depressor anguli oris - originates from the oblique line

- Buccinator - originates from the alveolar process

- Digastric anterior belly - originates from the digastric fossa

- Mylohyoid - originates from the mylohyoid line

- Geniohyoid - originates from the inferior portion of the mental spine

- Genioglossus - originates from the superior portion of the mental spine

- Superior pharyngeal constrictor - originates partially from the pterygomandibular raphe, which originates from the mylohyoid line

Muscles Inserting on the Mandible

- Platysma - inserts on the inferior border of the mandible

- Superficial masseter - inserts on the lateral surface of the ramus and angle of the mandible

- Deep masseter - inserts on the lateral surface of the ramus and angle of the mandible

- Medial pterygoid - inserts on the medial surface of the mandibular angle and ramus of the mandible

- Inferior head of the lateral pterygoid - inserts on the condyloid process

- Temporalis - inserts on the coronoid process

Physiologic Variants

Males generally have squarer, more prominent mandibles than females. This is due to the larger size of the mental protuberance in males and the decreased gonial angle. The gonial angle is 90 degrees in males, compared to 110 in females.

A bifid or trifid inferior alveolar canal may be present in rare instances. This can be detected on X-ray as a second or third mandibular canal. Branches of the inferior alveolar nerve commonly run through these extra foramina and can confer a risk for inadequate anesthesia during surgical procedures involving the mandible.[14]

A cleft chin can result from the inadequate or absent fusion of the mandibular symphysis during embryonic development. This often results in a depression of the overlying soft tissue at the midline of the mandible. This is a genetic condition that is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and found more frequently in the male population.[15]

Surgical Considerations

Orthognathic surgery, which includes mandible osteotomies and sagittal split osteotomies, is corrective jaw surgery performed to improve bite malalignment, sleep apnea, temporomandibular joint disorders, and structural issues such as cleft palate and micrognathia.

Mandible osteotomy is performed on patients with micrognathia, a condition in which the mandible is undersized. Micrognathia may result in pain and difficulty chewing; correction is often needed. This procedure is performed by transecting the mandible between the first and second molars bilaterally; the mandible is extended into its new position and stabilized with hardware.

Sagittal split osteotomy is performed on patients with prognathism, in which the mandible is oversized, causing an underbite. This procedure is performed by transecting the mandible bilaterally, repositioning it in a more posterior position, and stabilizing it with hardware.

Complications of these procedures include postoperative facial numbness due to nerve damage. Recovery from nerve damage typically occurs within three months of the procedure.

Clinical Significance

Mandibular fractures are most commonly caused by trauma and typically occur in two places. The parasymphysis is especially prone to fracture due to the incisive fossa and mental foramen. A direct blow to the mandible may cause a condylar neck fracture as the articular disk of the temporomandibular joint prevents it from moving posteriorly.[16]

A standard four-view series of X-ray films may be obtained in patients with traumatic mandibular injuries. Due to superimposed anatomy, mandibular series often do not provide sufficient detail to accurately diagnose condylar fractures. This issue is solved by using a reversed Towne view for imaging. Newer modalities such as CT scans have proven more sensitive than X-rays and are commonly employed.[17]

Dislocation of the mandible is most frequently in the posterior direction, but anterior and inferior dislocations may be observed. The patient may be unable to close their mouth or have an asymmetric jawline. Previous dislocation is the most significant risk factor. Manual reduction is often used to correct the injury. Barton bandages are used after reduction to hold the jaw in place and provide stabilization.

Other Issues

The mandible is a vital bone in terms of forensic evidence. Because the mandible progressively changes over an individual's life, it is routinely used to determine the age of the deceased.