Continuing Education Activity

This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of an injury to the median nerve and highlights the role of the healthcare team in managing patients with this condition. The purpose of this activity is to familiarize the reader with information about median nerve injuries, symptoms, management, and associated knowledge. The goal is to improve the healthcare team's ability to diagnose and treat this condition to improve patient outcomes.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of median nerve injuries as they relate to the anatomic course of the median nerve.

- Outline the appropriate history, physical, and evaluation of median nerve injuries based upon the provided clinical scenario.

- Review the management options available for median nerve injuries.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance information regarding median nerve injuries and improve outcomes.

Introduction

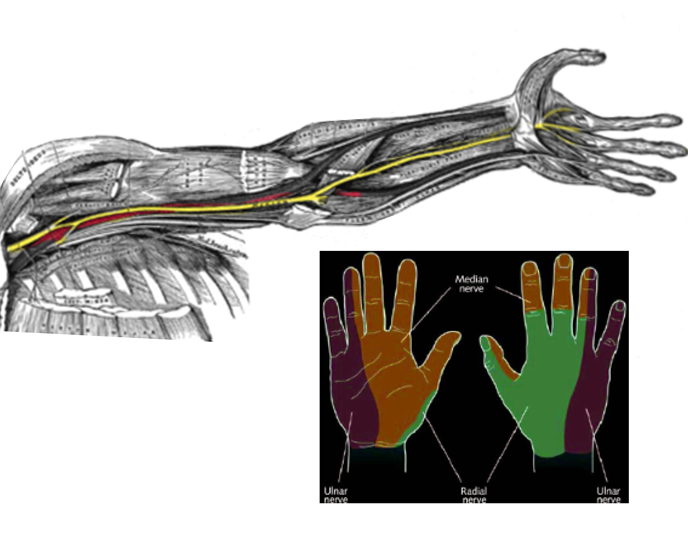

The median nerve, also called the 'eye of the hand,' is a mixed nerve with a role of primary importance in the functionality of the hand. It innervates the group of flexor-pronator muscles in the forearm and most of the musculature present in the radial portion of the hand, controlling abduction of the thumb, flexion of the hand at the wrist, and flexion of the digital phalanx of the fingers. The nerve allows the sensory innervation to the palmer face of the thumb, index, middle and radial side of the ring finger, and the entire palmar region of the radial half of the hand. It also provides sensitivity to the dorsal skin of the last two phalanges of the index and middle fingers.

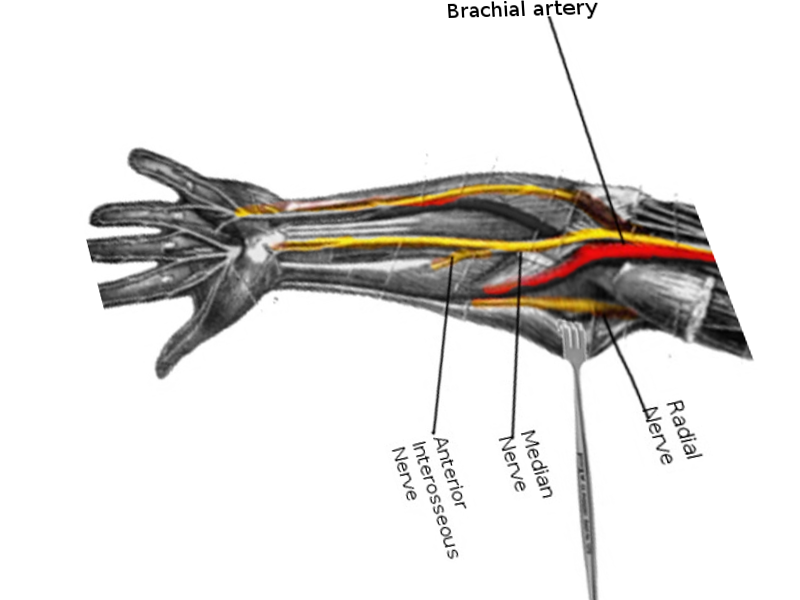

The nerve forms in the cervical area of the spinal cord from the medial and lateral cord of the brachial plexus. These cords form from the ventral primary rami of cervical nerve roots five to eight, as well as the first thoracic spinal segment. The median nerve descends medially to the brachial artery at the level of the humerus and enters the forearm between the two heads of pronator teres. The nerve is very superficial in the cubital fossa and lies deep to bicipital aponeurosis. In the forearm, the median nerve lies deep to the flexor digitorum superficialis and superficial to flexor digitorum profundus. It then enters the palm under the flexor retinaculum lateral to the tendon of flexor digitorum superficialis and posterior to the tendon of palmaris longus. Pathology and injury to the median nerve can occur anywhere along the length of the median nerve.

Of note, in the arm, there are no muscles innervated by the median nerve. Although a branch to pronator teres is innervated proximal to the elbow joint, there are a few vascular branches of the median nerve that supply to the brachial artery, and articular branches of the median nerve innervate the elbow joint. In the forearm, the median nerve innervates the flexor digitorum superficialis, pronator teres, the medial half of the pronator quadratus, the palmaris longus, flexor carpi ulnaris, and flexor carpi radialis. Furthermore, in the hand, the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus are innervated by the anterior interossei branch of the median nerve. Articular branches of the median nerve feed the carpal joints, distal radioulnar, and radiocarpal joint. Multiple communicating branches of the median nerve connect to the ulnar nerve. The median nerve innervates the muscles of the thenar compartments of the palm, flexor pollicis longus, abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and adductor pollicis. Also, the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve innervates the skin over the thenar eminences and lateral two and a half fingers on the palmar aspect of the hand and the skin over the two and a half fingers over the dorsum of the hand.

The median nerve can be affected by acute traumatic, chronic micro traumatic, and compressive lesions. The nerve can also become damaged during multiple-cause degenerative processes and neuropathies. The different types of lesions can affect the median nerve at various levels along its long path from the brachial plexus and axilla to the hand. Neuropathies mainly concern the distal territory. Peripherally, the median nerve can become compressed under the fascial sheath of the flexor retinaculum, which often causes burning pain, numbness, and tingling (neuropathic pain). This condition is known as entrapment syndrome or carpal tunnel syndrome. The carpal tunnel syndrome pain is explainable as a needle and pin sensation along the distribution of the median nerve. The condition is idiopathic and is also associated with hypothyroidism, pregnancy, and diabetes. Decreased sensation over a patient's thenar eminence is an indication of a medial nerve injury that is proximal to the carpal tunnel. The sensation of the thenar eminence receives its nerve supply by a branch of the median nerve, which is proximal to the carpal tunnel, the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Clinically, symptoms can be intermittent with flares and remissions.

Although a strong history can be clinically suggestive of median nerve pathology, there are several modalities that can aid in diagnosis. Plain film images, including a carpal tunnel view X-ray, can assist in diagnosis. Ultrasound is another imaging modality that is finding increasing use in diagnosing nerve pathology. Median nerve mononeuropathy is most common at the carpal tunnel. However, the prevalence of entrapment along other sites is estimated to be 7 to 10 percent.[1] Other sites include the ligament of Struthers, lacertus fibrosis, between the heads of the pronator teres, and the flexor digitorum superficialis.[1] Electromyography (EMG) also plays an important role in confirming the diagnosis and localizing the nerve and location. Treatment options vary depending on location. Non-invasive therapy is attempted first, including options such as braces to relieve pressure at sites of compression, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications to avoid repetitive stress. If those measures fail, surgical evaluation can be considered.

Etiology

Median nerve injuries occur by multiple mechanisms and can become injured at different sites along its course in the upper limb.

Common injuries to the median nerves include anterior shoulder dislocation, elbow dislocation, humerus fracture, midshaft radius fractures, stab wounds, prolonged placement of a tourniquet, and repeated use of crutches. However, these injuries are rarely in isolation and are often associated with radial or ulnar nerve neuropathies. The most common mechanisms of injury are listed below.

- Direct trauma at the wrist and elbow joints

- Accidental trauma in the axilla, wrist, and palm during a surgical procedure can damage the median nerve.

- The nerve may become injured in attempted suicide.

- Median nerve injury is associated with a fracture of the humerus, especially supracondylar fractures.

- Entrapment at the elbow between the two heads of pronator teres (pronator teres syndrome) and under the flexor retinaculum (carpal tunnel syndrome)

- The median nerve can be involved in generalized degenerative and demyelinating disorders.

- Neuropathy such as chemotherapy-induced peripheral chemotherapy[2]

While the majority of cases of carpal tunnel syndrome are idiopathic, several conditions can induce, or precipitate, the entrapment of the nerve at the elbow and, in turn, the development of the clinical picture. The etiology of pregnancy-induced carpal tunnel syndrome is fluid retention. Space occupying lesions, including tumors, fractured callus, osteophytes, and hypertrophic synovial tissue, can be secondary causes along with metabolic conditions such as hypothyroidism, pregnancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Infection is another secondary cause alongside alcohol use disorder and familial disorders. Connective tissue diseases are risk factors for carpal tunnel. Repetitive activities requiring repeated wrist extension and flexion, obesity, and recent menopause also have established links with carpal tunnel syndrome.[3] Increased pressure within the carpal tunnel leads to nerve compression and damage [4]. Repetitive motion and the use of vibratory tools increase the risk of carpal tunnel.[5]

Epidemiology

Median nerve injuries are the primary causes of emergency department access for peripheral nerve injuries. In the United States, there are about 8,000,000 reported cases of injuries per year.[6] Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most frequently encountered entrapment neuropathy of the upper extremity and is prevalent in up to 3% of the general population. The incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome is 105 cases per 100,000 person-years. Regarding gender, the syndrome occurs in 52 out of 100,000 cases for men and 149 cases out of 100,000 for women. The prevalence is 1% of men, and carpal tunnel syndrome is present in 7% of women, with a general population prevalence of 3%. The peak years of carpal tunnel are between the ages of 45 and 54. Bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome appears in up to 65% of cases.[7] In an older patient population ages 65 to 74, women were found to have a carpal tunnel for times more likely than men.

Carpal tunnel entrapment of the median nerve is the most common nerve mononeuropathy. However, 7 to 10% of median nerve entrapments occur more proximal along the nerve.[1] The supracondylar process is a bone spur along the medial distal humerus; entrapment at this site makes up approximately 0.5% of median nerve entrapments.[1] Other locations of median nerve entrapment include lacterus fibrosis at the pronator teres muscle and the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle. Symptoms similar to median nerve entrapment may occur with other syndromes as well, such as Martin-Gruber anastomosis.[1] The role of electromyography can help distinguish and isolate nerve damage and location.

Pathophysiology

In the case of median nerve involvement in a supracondylar fracture, the patient loses pronation at the superior and inferior radioulnar joints. The forearm remains in the supine position due to the paralysis of the pronator teres and pronator quadratus. There is also a loss of flexion at the wrist joint due to the paralysis of the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus.

Paralysis of flexor digitorum radialis will result in lateral deviation of the hand, loss of flexion at the interphalangeal joints due to paralysis of the flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus. Loss of flexion at the terminal phalanx of the thumb can occur due to the paralysis of flexor pollicis longus. The opponens pollicis is most likely to be lost due to the paralysis of the thenar muscles with associated wasting of the thenar muscles. The thumb is usually rotated and adducted and referred to as an "ape-like hand."

"Pointing finger" deformity is caused due to injury to the median nerve in the mid-forearm by paralysis of flexor digitorum superficialis. Loss of general sensations over the lateral three and a half fingers over the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hand can occur with median nerve injury. The area of the skin in median nerve injury can experience sensory loss, where the skin is warm and dry. In the case of long-standing vasomotor changes, the pulp of the fingers undergoes atrophic changes.

History and Physical

The effect of trauma on the median nerve depends on the injury site and may involve the palm, forearm, arm, or axilla. The damage to the nerve can lead to motor, sensory, and vasomotor loss. Most injuries to the median nerve occur at the wrist. Although carpal tunnel syndrome represents the main clinical picture, several injuries can affect the nerve. These lesions are addressable in a distal to proximal manner, from the wrist to the axilla and at the brachial plexus.

Wrist Lesions

Traumatic injuries to the median nerve at the wrist level are much more frequent, especially during wrist fractures. Nerve damage can range from simple compression by fracture stumps, to nerve contusion, to rare nerve tears. Moreover, on the wrist, the median nerve is very exposed to cutting injuries and penetrating objects that can cause its complete or partial section. Lesion of the palmar sensory branch of the median nerve, traumatic or accidental iatrogenic damages during surgery on the wrist can result in painful amputation neuromas.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Anatomically the carpal tunnel is formed from the flexor retinaculum superiorly and the carpal bones inferiorly; within the carpal tunnel lies the median nerve and nine flexor tendons. Symptoms can localize to the wrist or the entire hand as well as radiate into the forearm. In particular, the signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome include thenar weakness, numbness in the radial three and one-half fingers, and paresthesias. Other symptoms include burning like pain in the distribution of the median nerve. Symptoms can mimic the effects of an injury to the C6, C7 nerve roots.[8] The way to distinguish carpal tunnel syndrome from a nerve root injury is carpal tunnel syndrome is an isolated injury to the distal median nerve. Symptoms are typically worse at night and awaken patients from sleep. There is no triceps or weakness in wrist extension. Carpal tunnel is also distinguishable with the Tinel and Phalen tests. Cubital fossa tenderness or swelling can be a sign of median nerve injury and the loss of muscle strength in pronation, active wrist flexion. On exam, thenar atrophy can represent chronic median nerve injury. A positive Tinel sign is suggestive of carpal tunnel syndrome. A positive Phalen maneuver is also indicative of carpal tunnel syndrome.[8] Explanations of these specialized tests appear below.

A flick sign occurs when a patient is awoken from sleep with symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome and needs to flick their hands to relieve the symptoms. The test is 93% sensitive and 96% specific for carpal tunnel syndrome.[9] The hand elevation test is equally effective as the Phalen maneuver or the Tinel sign. Hand elevation tests can be completed with the patient lifting their hand above their heads for one minute, recreating symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome.[10]

Other specialized tests to be considered on the physical exams for carpal tunnel syndrome include the Phalen maneuver, Tinel sign, and median nerve compression test. The Phalen maneuver is when a patient flexes their wrist 90 degrees with their elbows in full extension. Recreation of symptoms of the carpal tunnel within 60 seconds is a positive test. A Tinel test is positive when rapid, repeated tapping over the volar surface of a patient's wrist in the area of the carpal tunnel recreates symptoms of carpal tunnel. Furthermore, a positive median nerve compression test is positive when applying direct pressure over the transverse carpal ligament recreates symptoms of the carpal tunnel within 30 seconds.

The severity index of carpal tunnel syndrome is either mild, moderate, and severe:

- Mild carpal tunnel syndrome is numbness and tingling in the median nerve distribution without motor or sensory losses. The patient's sleep does not suffer disruption, and there are no changes to the activities of daily living.

- Moderate carpal tunnel syndrome includes symptoms of mild carpal tunnel syndrome and sensory loss in the median nerve distribution and sleep becomes disrupted; there can also be some changes to hand function.

- Severe carpal tunnel syndrome includes symptoms of mild and moderate carpal tunnel syndrome, weakness in the median nerve distribution, and changes to the activities of daily living.

Pronator Syndrome

Pronator syndrome, or pronator teres syndrome, occurs when the pronator teres compresses the median nerve. This condition can look remarkably similar to carpal tunnel syndrome. In pronator syndrome, patients often complain of discomfort in their forearm with activity. An extended elbow and repetitive pronation can often reproduce the symptoms of pronator syndrome, numbness and tingling of the thumb, and the first two digits. The sensation is often intact to the forearm and digits pronator syndrome; however, there is often the loss of sensation over the thenar eminence. This presentation is another way of distinguishing pronator syndrome from carpal tunnel syndrome. The Phalen maneuver and the Tinel sign are also often negative in pronator syndrome. In pronator teres syndrome, the median nerve becomes entrapped as the nerve passes through the pronator teres; this is a syndrome typically seen in professional cyclists. The most common distribution of sensation loss is the lateral palm, but as mentioned above, also sensory loss over the thenar eminence.[4]

Anterior Interosseous Neuropathy

Anterior interosseous neuropathy is another form of median nerve injury. The anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve located at the elbow then moves into the anterior forearm. The anterior interosseous nerve innervates the flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, and the deep flexors of digits two and three. There is no cutaneous branch; thus, the neuropathy presents with muscle weakness, no sensory deficits.On physical exam, this can appear by the patient being unable to approximate the thumb and index finger. Patients are unable to pinch objects or make an "OK" sign with their index finger and thumb. An injury to the anterior interosseous nerve most commonly occurs with complex trauma, whereas an isolated injury is rare.

Elbow Lesions

The median nerve can be involved during fractures-dislocations of the elbow, both directly by the fracture stumps that, in case of particularly violent traumas, can tear the median nerve, or indirectly through the stretching of the nerve or acute compression by perineural hematomas. Again, the nerve can have involvement during the reparative fibrous processes that can incorporate and constrict it. In case of the reduction of the dislocation or in an attempt to realign the fracture fragments, the median nerve can remain trapped or imprisoned between the fracture stumps themselves or between the articular heads after a dislocation. Compressions of the median nerve at the elbow can occur both at the level of the fibrous laceration and the round pronator muscle. The former condition can cause painful neuropathic symptomatology with muscle weakness. Furthermore, a median nerve lesion can occur during normal elbow surgery such as elbow arthroscopy, rigid elbow correction, prosthesis, or fractures (iatrogenic damages).

Arm, Axillary, or Upper Lesions

Traumatic injury of the arm, such as humerus fractures, can rarely cause paralysis of the median nerve, whereas an acute traumatic injury from a deep wound is more frequent. Stab wounds, stab wounds, gunshot wounds, high energy injuries such as road accidents, or more complex brachial plexus injuries can induce nerve lesion at the axilla or upper. Damage at this level causes paralysis of all the innervated musculature of the median nerve and sensory impairment.

Evaluation

Tinel test and Phalen test are of fundamental importance for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. If the history and physical exam are inconclusive to differentiate between a nerve root injury and a distal median nerve injury, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study are diagnostic options.

A nerve conduction test can detect impairment in the median nerve conduction across the carpal tunnel while having normal conduction along everywhere else in its path. An EMG can be used to determine if there is pathology within the muscles innervated by the median nerve. Of note, the usefulness in EMG is in the exclusion of polyneuropathy or radiculopathy. Nerve conduction studies have been demonstrated to be up to 99% specific for the carpal tunnel, although it may be normal in patients with mild symptoms.[11][12]

According to the nerve conduction velocity, carpal tunnel syndrome can classify as:

- Mild carpal tunnel syndrome. Prolonged sensory latencies, a very slight decrease in conduction velocity. No suspected axonal degeneration.

- Moderate carpal tunnel syndrome. Abnormal sensory conduction velocities and reduced motor conduction velocities. No suspected axonal degeneration.

- Severe carpal tunnel syndrome. Absence of sensory responses and prolonged motor latencies (reduced motor conduction velocities).

- Extreme carpal tunnel syndrome. Absence of both sensory and motor responses.

On musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound, a cross-sectional area of 9 mm or more is 87% sensitive for carpal tunnel syndrome.[13] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and X-ray are typically not indicated for suspected carpal tunnel syndrome. MRI is an option for suspected medial nerve entrapment at the wrist. This imaging can be useful in diagnosis when the patient is not recovering from an expected course. The MRI can help identify hypertrophy of the synovium and a space-occupying lesion such as a ganglion cyst.

Treatment / Management

Management of median nerve injury depends on the etiology. Splinting is considered a first-line treatment option for mild to moderate carpal tunnel. Research shows it to be superior to placebo, but no single splint stands out as superior. However, a separate study has shown a neutral wrist splint to be twice as effective in symptomatic relief compared to that of an extension splint.[14][15] If initially starting with night splints, and the patient does not have relief after one month, the recommendation is to continue for another one to two months but add another conservative treatment modalities to the care plan. Splints can be worn at night or continuously, but have continuous use has not been shown to be superior to nighttime wearing the splint.[16][17]

Other conservative therapies include physical therapy, yoga, and therapeutic ultrasound. Again, the first-line for conservative management in the case of mild to moderate carpal tunnel are corticosteroid injections and night splints.[16] Combined conservative treatment modalities are the recommendation for carpal tunnel syndrome.[18][19] They are more effective than any modality used alone.[20] A local corticosteroid injection has been shown to delay the need for surgery at one year following an injection. The risks of a local corticosteroid injection include possible injection into the median nerve as well as tendon rupture. The recommendation is to do a carpal tunnel injection under ultrasound guidance to limit risks and improve the accuracy of the injection. When comparing 80 mg of methylprednisolone to 40 mg for a corticosteroid injection into the carpal tunnel, both groups were was less likely than placebo to have surgery at 12 months following the injection.[21]

Evidence does not support one technique over another; however, ultrasound-guided injections appear to be more effective than blind techniques.[22] A repeat corticosteroid injection may be offered six months following the initial injection. If symptoms recur after the second injection, then surgery is recommended. Oral prednisone at the dose of 20 mg for 10 to 14 days shows the improvement of patient’s pain related to carpal tunnel syndrome and hand function compared to placebo up to eight weeks following the medication course.[23] There is limited effectiveness of physical therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, and carpal bone mobilization. However, one randomized trial found yoga compared to wrist splints to improve patient symptoms for up to eight weeks.[24] The success of non-surgical options is variable, ranging from 20% to 93%, depending on the severity of symptoms.[18][25]

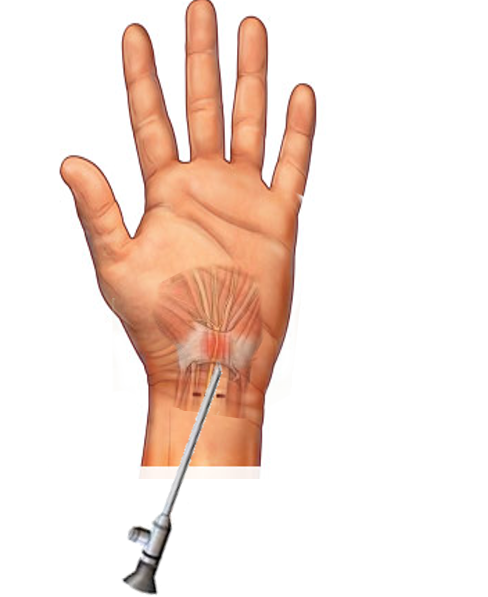

Patients with severe carpal tunnel symptoms who have failed conservative management after four to six months should receive an offer for surgical decompression. If a patient has failed conservative management and opts for surgical decompression, it is recommended to get electrodiagnostic studies prior to surgery to help determine underlying severity as well as prognosis. Consensus suggests carpal tunnel release surgery is more beneficial than no treatment at all and has demonstrated improved clinical outcomes compared to wrist splints. Endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release surgeries show improvement in patient symptoms. When comparing open to endoscopic carpal tunnel decompression, patients return to work one week earlier with endoscopic decompression. New evidence supports the use of ultrasound-guided carpal tunnel releases.[5]

Symptoms with mild compression of the median nerve tended to worsen over ten to fifteen months, while patients with moderate or severe involvement tended to improve. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome with splinting or surgical decompression can lead to complete or marked improvement at one year following therapy in 70 to 90 percent of patients.[26][27]

Treatment of pronator teres syndrome includes limiting activity that produces symptoms. NSAIDs, local corticosteroid injections into the tender points of pronator teres, and median nerve decompression surgery have also demonstrated effectiveness.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes cervical radiculopathy, motor neuron diseases, fibromyalgia, compartment syndrome, brachial plexopathy. The different clinical conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis can be schematically grouped:

- Dislocation of the interphalangeal joints, carpal-metacarpal joints of the thumb

- General demyelinating diseases

- Infection of the underlying palmar spaces

- Local muscular injuries around the thumb

- Rheumatoid arthritis involving the thumb joints

- Tenosynovitis involving the tendons of opponens pollicis, flexor pollicis longus, and adductor pollicis

Prognosis

The prognosis of the nerve injury depends on the severity of the injury and the time of repairs. Minor laceration with immediate surgical repairs with supportive precautions has the best prognosis and helps minimize the associated deformities.

Symptoms of carpal tunnel often resolve six months after the onset of symptoms. Prognosis is better the younger the patient, and prognosis is worse when there is a bilateral positive Phalen test on an exam. Most cases of pregnancy-induced carpal tunnel spontaneously resolve after delivery.

Conservative therapies often improve symptoms within two to six weeks. Maximal benefits for conservative therapies in carpal tunnel occur at three months. When one approach fails to improve symptoms after six weeks of the current management, another approach should merit consideration.[28]

Several predictors are associated with the failure of conservative/nonsurgical therapy.[25][29] Failure of conservative treatment often presents with symptoms occurring for greater than six-month duration, patients with constant paresthesias, patients greater than age 50, impaired two-point discrimination, positive Phalen’s occurring in less than 30 seconds, prolonged motor and sensory latency on EMG.

Surgical decompression has a successful outcome in roughly 70 to 90% of cases. Most patients note significant improvement at one week and can return to their normal routine two weeks post-operatively. However, some patients can take up to a year for a full recovery.[30]

Complications

Sensory fibers are more prone to damage from nerve compression compared to motor fibers; thus, paresthesias and numbness and tingling are often the first signs of carpal tunnel syndrome. Motor fibers are affected as the severity of carpal tunnel syndrome progresses. Patients often have weakness in thumb abduction and opposition. Fine motor skills become affected; patients have difficulty dressing themselves or opening jars. As sensory fibers die, the pain gradually subsides; while motor fibers die, the muscles atrophy. Patients may also lose their ability to determine two-point differentiation between two objects, 6 mm apart.[31][32]

Pillar pain is common with surgery, pain lateral to the site of surgical release.[30] Surgical decompression failure is often attributable to the development of fibrosis or failure to completely release the flexor retinaculum.[33] Surgical revision is necessary in these cases.

Complications of surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome can include the following:

- Inadequate division of the transverse carpal ligament[34]

- Injuries of the recurrent motor and palmar cutaneous branches of the median nerve

- Vascular injuries of the superficial palmar arch[34]

- Lacerations of the median and ulnar trunk

- Postoperative wound infections[35]

- Painful scar formation

- Complex regional pain syndrome[35]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Median nerve injury most commonly occurs from posture or workplace ergonomics, direct trauma, or physiological conditions such as pregnancy.

- Diagnosis is largely made by history and physical exam

- If experiencing symptoms worse at night, relieved by "shaking off" hand(s), this is known as the "flick sign" and is suggestive of median nerve entrapment[36]

- A physical exam includes tests such as the Phalen sign and Tinel sign which can be highly suggestive of nerve entrapment

- X-ray and ultrasound are two modalities that can aid in the diagnosis

- Electromyography (EMG) is used to help quantify location and amount of nerve damage if present

- The treatment plan is conservative, including adjusting workplace ergonomics, use of braces, and physiotherapy

- Most cases of pregnancy-related carpal tunnel syndrome resolve after delivery[37]

- Steroid injections can be a highly effective first-line treatment option[38]

- Refractory cases may require surgical consideration and release of the transverse carpal ligament

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Median nerve injury and the associated pain, paraesthesias, and upper extremity weakness that occurs require prompt treatment ranging from night splints to surgery. The cause of median nerve injury may be due to a myriad of diagnoses, including idiopathic, injury, overuse, and type two diabetes. The history and physical exam may usually reveal nerve impairment without imaging studies.

It is crucial to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists. The diagnosis can be made by any healthcare provider, most commonly by primary care physicians. However, several other sub-specialties encounter and are involved in the care of median nerve entrapment, including but not limited to physiatrists, neurologists, sports medicine physicians, orthopedists, hand surgeons, and radiologists. Conservative management plays a primary role, especially in the acute phase. Physical and occupational therapists are vital members of the interprofessional group during the healing process both for conservative management of median nerve injury and in postoperative recovery after median nerve decompression. In cases where evidence is minimal or not definitive, expert opinion from the specialist may help to recommend the type of imaging or treatment. If the clinician first attempts steroid injections to ward off surgery, the pharmacist can assist with the dosing and preparation of the drug. Continued neuropathic pain can also be addressed pharmaceutically, making pharmacists an essential contributor to the team.

The outcomes of a medial nerve injury depend on the cause and severity. Nurses can also coordinate postoperative physical therapy, with both the therapist and nurse providing information on patient progress to the clinical team.

Prompt consultation with an interprofessional team of specialists is the recommendation to improve outcomes with these conditions. Collaboration, shared decision making, and communication between interprofessional team members are key elements for a good outcome. [Level 5]

The earlier signs and symptoms of a complication get identified, the better is the prognosis and outcome. [Level 3]