Continuing Education Activity

This activity addresses the topic of median nerve palsy in great detail. The median nerve is a critical neurological structure in the upper extremity for function and use of the hand. Palsies of the median nerve can, therefore, be debilitating and sometimes painful. The goal of this activity is to familiarize practitioners with the clinical presentation of median nerve palsies and its mimicking conditions, as well as to review relevant anatomy and treatment options.

Objectives:

- Review the anatomy of the median nerve, with special attention to how to identify compressive neuropathies based on location.

- Describe the appropriate evaluation of median nerve palsies.

- Outline the appropriate treatment options for patients suffering from a median nerve palsy.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to appropriately treat median nerve palsies and improve clinical outcomes.

Introduction

The median nerve is a continuation of the middle and lateral cords of the brachial plexus that receives innervation from all roots of the brachial plexus (C5-T1). After leaving the shoulder, it travels with the brachial artery under the ligament of Struthers, the bicipital aponeurosis, and the two heads of pronator teres into the anterior compartment of the forearm. Compression at this point in the course of the median nerve results in pronator syndrome. Just distal to the elbow joint, the median nerve gives off its first terminal branch: the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN).

The AIN travels in the deep flexor compartment of the forearm between the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) until it terminates in the pronator quadratus (PQ). The AIN provides motor innervation to the FPL, the FDP to the index and middle fingers, and the PQ. Note that the ulnar half of FDP to the little and ring fingers is innervated by the ulnar nerve.

The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve branches from the median nerve in the forearm, and travels to the hand to innervate the lateral (radial) aspect of the palm. Importantly the palmar cutaneous nerve does not travel through the carpal tunnel, which explains why sensation to the lateral palm is typically spared in carpal tunnel syndrome.

After giving off the AIN and the palmar cutaneous branch, the median nerve travels distally between the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS). In the forearm, the median nerve provides motor innervation to all superficial flexors of the forearm, while the AIN provides motor innervation to the deep flexors. The exception to this is the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is innervated by the ulnar nerve. The FCU is the strongest flexor of the wrist and receives its innervation from the ulnar nerve.

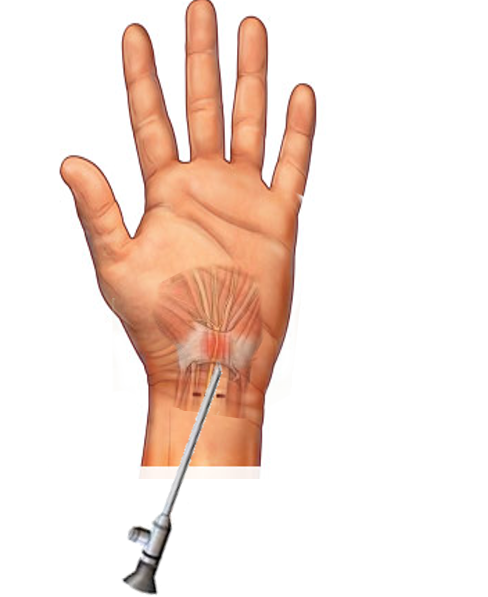

The median nerve then enters the hand through the carpal tunnel. There are nine other anatomic structures in addition to the median nerve passing through the carpal tunnel: the four tendons of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), the four tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), and the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) tendon. The carpal tunnel is defined by the proximal carpal row dorsally and the transverse carpal ligament palmarly. Incision and release of the transverse carpal ligament is the treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome.

In the hand, the median nerve divides into two branches: the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve and the digital cutaneous branch of the median nerve. The recurrent motor branch of the median nerve is a radial structure at the level of the carpal tunnel and provides motor innervation to the muscles of the thenar eminence, including abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and the superficial head of the flexor pollicis brevis. Of note, the deep head of flexor pollicis brevis and the adductor pollicis brevis receive their innervation from the ulnar nerve.

The digital cutaneous branch of the median nerve further branches into the proper palmar digital branch and the common palmar digital branch. The proper palmar digital branch is more radial and provides the digital nerves to the thumb and the radial digital nerve of the index finger, which also supplies the first lumbrical. The common digital branch then branches into the ulnar digital branch of the index finger, both digital nerves of the middle finger and the radial digital nerve of the ring finger, which also provides innervation to the second lumbrical. Note that other than the aforementioned muscles of the thenar eminence and the radial two lumbricals, all other intrinsic muscles of the hand receive motor innervation from the ulnar nerve.

While detailed, an understanding of the anatomy of the median nerve and its branches can help practitioners to accurately diagnose the cause of median nerve pathology and determine the appropriate treatment. Palsies of the median nerve may be acute, requiring urgent intervention or chronic, indicating a more conservative approach. Therefore, a history and physical exam are the most important tools a practitioner can employ for appropriate management of such conditions.

Etiology

Compression, stretch, or traumatic disruption of the nerve may result in median nerve palsies. As noted, the key to providing appropriate care to patients with median nerve palsy is accurately identifying the source of nerve dysfunction through a careful physical examination and when needed, confirming injury with advanced diagnostic techniques. Penetrating injuries to the upper arm can result in a median nerve palsy. Injuries to the median nerve at this location often result in a vascular injury given the nerve’s proximity to the brachial artery. Such an injury to the brachial artery will most often result in an under perfused extremity, constituting a vascular emergency. There have also been case reports of damage to the median nerve in the upper extremity after a brachial angiography.[1][2]

Compression of the median nerve can occur at multiple sites in and around the elbow. Median nerve impingement may occur at the ligament of Struthers and supracondylar process of the medial epicondyle, or slightly more distal at the bicipital aponeurosis as well as between the heads of pronator teres.[3]

Penetrating injuries between the elbow and wrist may result in laceration or injury to the median nerve or the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) and the palmar cutaneous branches of the median nerve.

Most commonly, palsies of the median nerve are caused by compression at the carpal tunnel. Known as carpal tunnel syndrome, symptoms are often alleviated by conservative measures but have a high treatment success rate when surgical intervention is required.

Epidemiology

A few of the median nerve pathologies have epidemiological data on which to rely when considering a patient’s symptoms and or presentation.

The mean age for patients with pronator teres syndrome is approximately 50 years, with men having a statistically significant increase in incidence compared to women.[4]

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most frequently encountered median nerve pathology, with a reported 105 cases per 100000 people per year. Women have a 3 times higher incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome compared to men. Like pronator teres syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome peaks around age 50 but also frequently present in the older population.[5][6] Patients with diabetes and thyroid disease are at an increased risk for carpal tunnel syndrome, and therefore a thorough medical history can help practitioners better diagnose higher-risk patients.[7]

History and Physical

When median nerve palsy is suspected, a history should investigate the timing of onset and duration of symptoms. Practitioners should identify any temporal factors, such as pain that is worse at night or with activity, and any other aggravating or relieving factors affecting a patient's symptoms.

Patients with diabetes and thyroid disease are at increased risk for carpal tunnel syndrome, and therefore a thorough medical history can help practitioners better diagnose higher-risk patients.[7]

Physical exam should focus on identifying all motor and sensory deficits and using these findings to identify the locus of a patient's pathology. As discussed, median nerve injury most commonly presents from compression at the carpal tunnel, but compression also may occur at the level of the elbow as with pronator syndrome. Indeed, a careful practitioner should also consider nerve compression injury more proximally in either the brachial plexus or cervical spine, where disc or foraminal pathology can create symptoms in the median nerve distribution. Physicians should not overlook any vascular injury, especially in the setting of a high median nerve injury in the upper arm. Urgent intervention may be required in acute cases, such as an expanding hematoma, or when worsening motor deficits are identified to prevent permanent progression of nerve palsy.

Compression of the median nerve is most common at the level of the carpal tunnel, where the nerve enters the hand under the transverse carpal ligament. The median nerve provides sensation to the index, middle, and ring fingers via the digital nerves. It is important to note that sensation to the radial palm is provided by the palmar cutaneous branch, which branches proximal to the transverse carpal ligament in the forearm and therefore is not a component of carpal tunnel syndrome. With carpal tunnel syndrome, practitioners may observe weakness in the thenar eminence. Isolation of the opponens pollicis by asking the patient to palmarly abduct the thumb helps to identify weakness in the median nerve. It is worth noting that the flexor pollicis longus and the flexor digitorum profundus to the index and middle fingers should be intact as they are innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve which branches from the median nerve just distal to the elbow.

Phalen's test is used to assess for compression at the carpal tunnel. It is considered positive when there is a reproduction of symptoms after full flexion of the wrist for 60 seconds.[8]

Tinel's sign may also be used to assess for compression at the carpal tunnel. It is considered positive when a repeated tapping over the carpal tunnel reproduces symptoms in the hand consistent with median nerve pathology.

The next most likely site of a median nerve compression injury would be at the level of the cubital fossa in pronator syndrome. Pronator syndrome is frequently misdiagnosed as carpal tunnel syndrome. This common error leads to significant morbidity caused by a delay of appropriate care. Compression of the median nerve in the cubital fossa would have significant similarities to the presentation of carpal tunnel symptoms, but an understanding of the anatomy will reveal subtle differences in the examination. Most obviously, pronator syndrome results in compression proximal to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve and thus may result in numbness over the radial palm, distinguishing itself from carpal tunnel syndrome. Similarly, compression proximally at the ligament of Struthers occurs before the divergence of the anterior interosseous nerve. Theoretically, patients could present with weakness in the deep flexors such as flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) to the index and middle fingers, as well as to the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) which are both innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve. Placing the elbow in full extension and pronating the arm may reproduce symptoms of pronator syndrome, and may help practitioners distinguish between pronator syndrome and carpal tunnel syndrome.[9]

Diagnosticians must always evaluate the neck in patients with presumed median nerve injury or carpal tunnel syndrome. Double crush syndrome is defined as an injury to a nerve at both a distal site of compression as well as proximally such as in the case of a coexistent cervical disk herniation or foraminal stenosis. This condition is most commonly identified when patients have an unsatisfactory resolution of symptoms after a carpal tunnel release.[10] Osterman et al. found in a prospective study that patients who suffered from double crush syndrome reported more "paresthesias" rather than "numbness" compared to patients who had isolated carpal tunnel syndrome. He also found that grip strength was decreased more with double crush syndrome compared to carpal tunnel syndrome.[11] Of note, radiography of the cervical spine is not currently recommended for evaluation of double crush syndrome by current literature, particularly in the older patient population as there is a very high incidence of asymptomatic degenerative changes of the spine. MRI may be useful but is cost-prohibitive and not necessary in most cases. Therefore, history and physical examination with documentation of such examination techniques as Spurling's cervical spine maneuver to identify cervical nerve root compression, are important tools to identify double crush syndromes.[10][12][13]

Evaluation

As in all areas of medicine, a thorough physical examination is the most important tool of the diagnostician in the diagnosis of median nerve palsies. In the setting of acute fractures or trauma, x-rays should be employed to assess for concomitant osseous injuries, which may cause injury or compression to the nerve but will have little utility in the assessment of nerve injury.

Ultrasound is a useful tool and may reveal the etiology of nerve compression. Electromyography is another commonly used tool in the diagnosis of compression neuropathies and muscle denervation. Compressive neuropathies result in increased distal latency and decreased conduction velocity when evaluated by EMG. Fasciculations within the innervated musculature are a sign of denervation and warrant a more urgent surgical decompression.[14]

Treatment / Management

Acute injuries to the median nerve where an obvious source of stretch or compression is identified, such as in the case of compartment syndrome or an expanding hematoma often require urgent surgical decompression to prevent permanent damage to the motor endplate units of the muscle. However, as a general rule, most compressive neuropathies of the median nerve should undergo a trial of non-operative treatment.

Night splinting is the first-line treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Splints should hold the wrist in a neutral position, as hyperextension of the wrist increases the pressure within the carpal tunnel. Corticosteroid injections also may be used in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome and delay time to surgery for up to 1 year but are not without risks such as injecting into the nerve itself.[15][16][17]

Pronator syndrome should similarly be treated conservatively after an initial evaluation. Splinting and anti-inflammatory medications are the mainstay of initial treatment.[18] If a patient does not experience relief from non-operative modalities and has a diagnosis confirmed by electrodiagnostic studies, surgeons should consider a surgical release of the offending compressive structures as a viable treatment option. As there are many sites of potential compression at the elbow, the release of all potential sites of compression should be considered, including the ligament of Struthers, the lacertus fibrosis, and the fascia of the pronator teres.[19]

Differential Diagnosis

An understanding of the anatomy of the median nerve is required to properly identify median nerve palsies and differentiate them from radial or ulnar nerve palsies. Each of these nerves has specific sensory and motor innervation patterns that distinguish themselves on careful physical examination.

Cervical radiculopathies may fool diagnosticians, as the median nerve receives innervation from C5-T1. An understanding of nerve root anatomy can help to better distinguish a nerve root palsy from a more peripheral injury to the median nerve.

Parsonage-Turner syndrome or neuralgic amyotrophy is defined as transient neuritis of the brachial plexus. It is characterized by abrupt unilateral shoulder pain, followed by progressive weakness, reflex changes, and sensory abnormalities classically following a viral illness. The etiology is thought to be an autoimmune response to viral antigen. While a specific inciting event may be difficult to ascertain, a proper history should include a history of recent illness.[20]

Prognosis

Patients who undergo open carpal tunnel release have good to excellent long-term outcomes after a carpal tunnel release 70% to 90% of the time. Diabetes does not appear to affect outcomes of carpal tunnel release despite being a risk factor for the development of carpal tunnel.[21] One study suggested that even patients who have double crush syndromes experienced good to excellent results with carpal tunnel release in 11 out of 15 cases.[22]

Patients who are diagnosed with pronator teres syndrome requiring nerve release typically return to full duty in 6 weeks. If tendon transfers are required, return to full duty is delayed to 10 to 12 weeks.[19]

Complications

Damage to surrounding neurovascular structures is a concern with any surgical decompression procedure. Iatrogenic injury to the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve is the most common complication associated with carpal tunnel release. Many anatomic variations of the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve have been identified, but a dissection of the nerve is not routinely recommended. Instead, current recommendations are to avoid transecting the transverse carpal ligament too radially, as this increases the risk of iatrogenic injury to the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve.[23][24]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients who have symptoms of numbness, paresthesias, pain, or weakness of the upper extremity should be evaluated by a clinician for evaluation to determine the source of their symptoms and to identify an appropriate treatment plan going forward. Acute processes may need early surgical intervention, but most presentations warrant a trial of non-operative intervention.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Proper diagnosis of median nerve palsies is dependent on physician's and mid-level practitioner's understanding of the relevant anatomy and etiology of median nerve injuries. Hand and upper extremity surgeons must work closely with primary care providers, who typically make the initial diagnosis, neurologists who offer confirmatory testing in the form of electromyography and other diagnostic studies, and their staff to correctly identify and treat the causes of median nerve palsy.

Outcomes are dependent on the etiology of the patient's symptoms, as well as the severity of injury to the median nerve. A collaborative effort between all members of the interprofessional team is critical for optimizing patient outcomes. [Level 5]