Continuing Education Activity

Aseptic meningitis is the inflammation of the brain meninges caused by various factors, leading to negative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) bacterial cultures. The condition is diagnosed through CSF pleocytosis, with an elevated white blood cell count. Aseptic meningitis is prevalent and typically benign, but the clinical manifestations can vary widely based on the underlying cause and the patient's immune status. Close evaluation and treatment involving an interprofessional team are crucial for effectively managing patients with aseptic meningitis.

This activity explores the diverse etiologies of aseptic meningitis, the broad spectrum of clinical presentations associated with aseptic meningitis, and the significance of an interprofessional approach to patient care. Clinicians engaged in this activity will enhance their diagnostic skills, broaden their understanding of the condition's complexities, and refine their approach to managing patients with aseptic meningitis. By integrating this knowledge into their clinical practice, clinicians will be better equipped to deliver high-quality care, improving patient outcomes and safety.

Objectives:

Differentiate between various etiologies of aseptic meningitis while understanding the unique features associated with viral, bacterial, and noninfectious causes and considering factors like immune status and patient history.

Implement effective screening methods, utilizing appropriate diagnostic tests and criteria to identify aseptic meningitis in patients presenting with compatible symptoms promptly.

Implement evidence-based interventions tailored to the specific etiology of aseptic meningitis, including antiviral therapies, supportive care, and, when applicable, collaborating with specialists for targeted treatments.

Collaborate with interdisciplinary team members, including infectious disease specialists, neurologists, nurses, and pharmacists, to improve care coordination.

Introduction

Aseptic meningitis is a term used to describe inflammation of the meninges, the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, caused by various factors and characterized by negative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) bacterial cultures. This condition is typically diagnosed based on CSF pleocytosis, indicated by an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of more than 5 cells/mm³.[1] Aseptic meningitis is a prevalent and generally benign inflammatory disorder affecting the meninges.[2]

Viruses, such as herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), enteroviruses, and arboviruses are the most common causes of aseptic meningitis.[1][2][3] However, aseptic meningitis can also be triggered by diverse factors, including infections caused by mycobacteria, fungi, spirochetes, parameningeal infections, medications, and malignancies. Notably, aseptic and viral meningitis are not interchangeable, highlighting the wide array of potential causes. The clinical manifestations of aseptic meningitis can vary significantly based on the affected individual's underlying cause and immune status. Patients with deficient humoral immunity, including neonates and individuals with agammaglobulinemia, are particularly at risk for negative outcomes in cases of aseptic meningitis.[1][2][4]

Etiology

The causes of aseptic meningitis can be broadly classified into infectious and noninfectious origins. Despite progress in diagnostic methods, only 30% to 65% of cases reveal a precise cause.[5] Cases without identified causes are termed idiopathic.[1]

Infectious causes of aseptic meningitis include viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, with viruses being the predominant agents.[2] Among viral causes, enteroviruses (such as coxsackie and enteric cytopathic human orphan [ECHO] viruses) account for over half of the cases, followed by HSV-2, West Nile virus, and varicella-zoster virus (VZV).[2][5] Other viruses associated with aseptic meningitis include respiratory viruses (adenovirus, influenza virus, rhinovirus), mumps virus, arbovirus, HIV, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.[2][5][6]

Bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections leading to aseptic meningitis are less common than viral infections. Bacterial causes may arise from partially treated meningitis, parameningeal infections (such as epidural abscess and mastoiditis), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, endocarditis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Treponema pallidum, and leptospirosis. Fungal infections can be attributed to Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Blastomyces dermatitides. Parasitic causes of aseptic meningitis include Toxoplasma gondii, naegleria, neurocysticercosis, trichinosis, and Hartmannella.[7][8]

Regarding the noninfectious causes of aseptic meningitis, these etiologies can be categorized into 3 main groups:[1]

- Systemic diseases involving meningeal inflammation, such as sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Drug-induced aseptic meningitis is most commonly associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics (sulfamides, penicillins), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and monoclonal antibodies

- Neoplastic meningitis is linked to either metastasis from solid cancers or lymphoma/leukemia.

Aseptic meningitis triggered by specific vaccines has been documented, notably following immunizations such as measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) and varicella, yellow fever, rabies, pertussis, and influenza vaccines.[9][10][11] Recent reports have suggested its occurrence even after the meningococcal vaccination.[12]

Epidemiology

The precise annual incidence of aseptic meningitis remains uncertain due to underreporting.[8] This condition can affect individuals of all ages but is more prevalent in children than adults.[2] In the US, the overall incidence is estimated to be 11 cases per 100,000 people per year, with a rate of 7.5 cases per 100,000 adults, and found to be 3 times more common in males than females, without any particular age or racial predilection.[2]

Aseptic meningitis leads to 26,000 to 42,000 hospitalizations annually in the US.[2] Studies in Europe have indicated an incidence rate of 70 per 100,000 among children younger than 1 year, 5.2 per 100,000 among children 1 to 14, and 7.6 per 100,000 in adults.[8]

In a study conducted in South Korea involving children, the incidence of aseptic meningitis showed a relatively even distribution across age groups, with higher rates observed in children under 1 year and those aged 4 to 7. The male-to-female ratio was 2 to 1 in this population.[13] Although aseptic meningitis can occur throughout the year, there are distinct peak periods, particularly during the summer months in temperate climates, when the incidence is notably higher.[2][8][13]

History and Physical

No aspect of the clinical history possesses sufficient sensitivity or specificity to establish a definitive diagnosis. Therefore, a thorough patient history is crucial, given the broad range of potential causes. The history should encompass inquiries about exposure to sick contacts, recent travel, substance use, sexual history, preceding or concurrent infections, and recent medication use, considering the possibility of drug-induced aseptic meningitis.[2][7]

When assessing patients clinically, it is crucial to recognize the differences in how children and adults may manifest symptoms. Adults often report symptoms such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, malaise, weakness, stiff neck, and photophobia.[2][7] Unlike bacterial meningitis, the onset may be less acute, and altered mental status is not a common presentation.

In contrast, children exhibit less specific symptoms, including fever, concurrent respiratory issues, rash, and irritability.[2][7] Neonates and infants less than 3 months of age may display a bulging anterior fontanelle and irritability as notable signs.[2] Specific factors like premature birth, maternal illness, elevated serum WBC count, low hemoglobin levels (<10.7 mg/dL), and the onset of symptoms within the first week of life necessitate a prompt and thorough evaluation and management approach in neonates.[2][14]

Nuchal rigidity (with a sensitivity of 70%) and fever (sensitivity of 85%) are prevalent physical signs observed in children and adults. Kernig and Brudzinski's signs, while highly specific at 95%, have limited utility due to their low sensitivity of 5%. Depending on the underlying cause, additional associated findings may be present.[2][4]

Evaluation

In recent years, although the cause of aseptic meningitis remains unidentified in up to two-thirds of cases, advances in diagnostic techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing, have facilitated the identification of pathogens. Similarly, substantial progress has been achieved in detecting and diagnosing autoimmune or paraneoplastic neurological syndromes.[2]

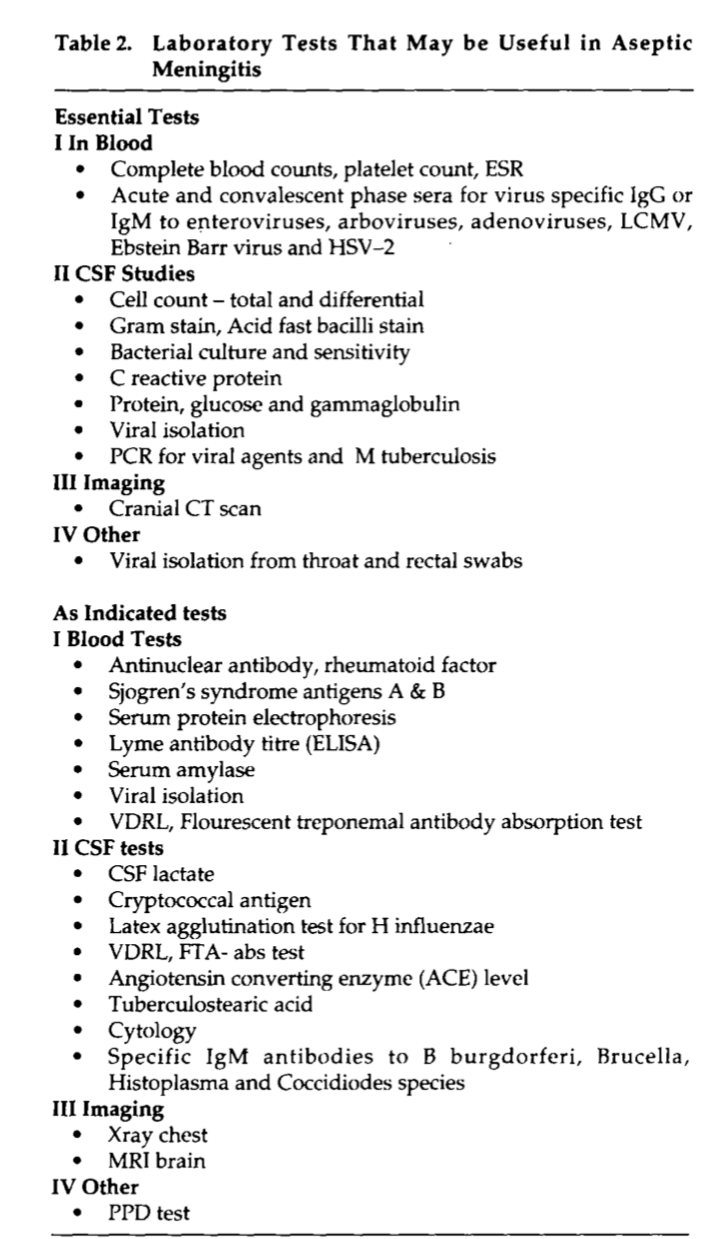

The initial assessment should involve laboratory testing to explore other potential causes of the symptoms (see Image. Laboratory Evaluation for Aseptic Meningitis). This evaluation usually includes a complete blood count (CBC) with platelet count, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and testing for immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) for enterovirus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and HSV.[2]

A lumbar puncture (LP) is essential for collecting CSF to establish a definitive diagnosis.[2][4][7] During CSF analysis, it is crucial to assess cell count, measure glucose and protein levels, perform a gram stain, conduct cultures, and employ bacterial PCR (typically targeting Neisseria meningitides, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. Specific viral PCR studies should also be selected based on the patient's clinical presentation. Other tests to consider include syphilis serology, tuberculosis (TB) testing, and serum HIV testing. Viral CSF PCR can detect enterovirus, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, varicella-zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), EBV, and arbovirus.[2][4][7]

Typical CSF findings in patients with aseptic meningitis include an opening pressure that is either normal (<180 mmH2O) or slightly elevated. Glucose levels are usually normal to mildly decreased, while protein levels are normal to mildly elevated (<200 mg/dL). The cell count ranges from 10 to 1000 cells per microliter, with an initial predominance of neutrophils (>50%) that gradually shifts toward lymphocytes (>80%) over time.[2][4][7] For patients in the US presenting between June and September, it is advisable to test for West Nile virus IgM in the CSF or serum.[15]

Significant differences exist between adults and children in the presentation and laboratory findings.[7] These differences often require specialized approaches in diagnosis and treatment tailored to each age group, emphasizing the importance of age-specific considerations in managing patients with aseptic meningitis.

Adults typically report symptoms such as headache, nausea and vomiting, neck stiffness, malaise, and photophobia. They are more likely to exhibit nuchal rigidity during examinations compared to children. Fever, concurrent respiratory illness, and rash are signs and symptoms that are more commonly observed in children.[7] Just as physical findings can differ, adult patients tend to exhibit a higher CSF WBC count and elevated CSF protein levels in the initial CSF evaluation than the pediatric population. Conversely, children often present with more CSF neutrophilic pleocytosis and higher leukocyte counts than adults.[4][7]

When interpreting CSF fluid results in neonates and young infants, applying age-adjusted values for leukocyte counts is crucial. In this population, up to 57% of children with aseptic meningitis exhibit a predominance of neutrophils in the CSF, emphasizing that relying solely on cell type cannot discriminate between aseptic and bacterial meningitis in children.[4]

Drug-induced aseptic meningitis, in particular, can often present with few laboratory abnormalities. Therefore, clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion and thoroughly assess the patient's medical history, including all medications they might be taking and their respective dosages.[2][4]

While distinguishing between aseptic and bacterial meningitis can be challenging, specific tools have been developed to aid the diagnostic process. The bacterial meningitis score, with a sensitivity of 99% to 100% and a specificity of 52% to 62%, stands out as the most specific tool currently accessible. Other laboratory findings, such as procalcitonin, serum C-reactive protein (CRP), and CSF lactate levels, can provide valuable insights to differentiate between aseptic and bacterial meningitis.

Before conducting an LP, if there is suspicion of elevated intracranial pressure caused by a space-occupying lesion or inflammation, it is advisable to obtain a head computed tomography (CT) scan before proceeding with the LP, as recommended.[4][16] A CT scan can offer an alternative diagnosis, eliminating the need for the LP. CT scans are typically unnecessary in neonates and infants with open fontanelles. For this age group, head ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality.[4][17]

Research has demonstrated that imaging might be safely avoided if all criteria are absent: age greater than or equal to 60, history of central nervous system disease, immunocompromised state, altered mental state, seizure within one week of presentation, and neurological deficits.[2][4] These guidelines help healthcare professionals make informed decisions, ensuring appropriate and targeted use of imaging resources in patients suspected of having neurological conditions.

Treatment / Management

Early recognition of the likely cause of meningitis is vital for initiating treatment promptly. Initial patient stabilization is crucial, and studies have demonstrated the benefits of intravenous fluids (IV) administered over 48 hours.[4] If bacterial meningitis is suspected, it is imperative to promptly start empiric antibiotics, ensuring broad coverage based on the most likely pathogens within specific age groups, especially in pediatric cases.[4]

Ideally, obtaining CSF fluid should precede antibiotic administration. However, initiating antibiotic therapy promptly is essential if this would cause a delay in treatment or if the patient is critically ill. Additionally, it is crucial to place the patient on droplet isolation precautions until the cause of the infection is identified. If HSV or (VZV) is suspected, intravenous acyclovir should be included in the empiric treatment regimen.[4]

If the CSF fluid results are more consistent with aseptic meningitis, discontinuing antibiotics should be considered, considering the patient's initial presentation and clinical status. Management of viral meningitis (excluding HSV and VZV) primarily involves supportive care.[4] Specific treatments for various bacteria, fungi, and others are beyond the scope of this activity. However, as discussed earlier, these treatments should be tailored based on individual clinical presentation and underlying health conditions.

Steroids are employed as adjunctive therapy to mitigate the inflammatory response. Dexamethasone, administered 10 to 20 minutes before or concurrently with antibiotics, is supported by evidence, even in cases where the etiology is initially unknown while awaiting culture results.[4] Research has demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing short-term neurologic sequelae and hearing loss, although this benefit is more pronounced in cases of bacterial meningitis.[18]

A repeat LP is generally unnecessary but should be considered for patients whose clinical condition does not improve after 48 hours. Continued monitoring and reevaluation of the patient's neurological status are essential in determining the appropriate course of action, ensuring comprehensive and responsive care.

After confirming the diagnosis of aseptic meningitis and ensuring the patient's clinical stability, discharge home is usually appropriate except for cases involving older patients, immunocompromised individuals, and children with pleocytosis. Home care instructions should be tailored to specific etiology when discharging the patient. For instance, patients diagnosed with enterovirus should be instructed to maintain excellent hand hygiene and avoid sharing food, as the virus is primarily transmitted via the fecal-oral route.[2][4]

Supportive treatment is essential for all patients, involving pain management and fever control using antipyretics such as acetaminophen, paracetamol, and ibuprofen. In cases of drug-induced meningitis, discontinuing the causative drug is crucial. If necessary, the medication should be replaced with an alternative that does not provoke meningeal irritation.[2][4]

Differential Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms of aseptic meningitis are frequently vague and nonspecific, leading to a broad range of possible diagnoses. Headache and fever, among the most common symptoms, significantly shape the differential diagnosis.[2][8]

Bacterial meningitis is the most concerning and prevalent alternative cause and should be the default diagnosis until ruled out. Patients with the appropriate clinical presentation should also be evaluated for intracranial hemorrhage, especially subarachnoid hemorrhage. Additionally, neoplastic disorders such as leukemia and brain tumors, other types of headaches like migraines, and inflammation of brain structures such as brain abscess and epidural abscess should be considered in the differential diagnosis.[2][8]

Fever originating from nearly any source can manifest with headache and neck stiffness as associated symptoms. Conditions like urinary tract infections and pneumonia may also present with headaches, body aches, and fever. Consequently, conducting a thorough investigation for infectious sources is an integral aspect of every diagnostic workup.[2][8]

Several causes of aseptic meningitis may exhibit most or all symptoms without actual meningeal involvement. Viral syndromes, in particular, frequently lead to symptoms such as headaches, muscle aches, weakness, and fever, even without direct meningeal inflammation.[2][8]

The wider range of differential diagnoses includes anemia, a condition known for causing headaches and weakness. Furthermore, the list extends to conditions like carbon monoxide exposure, child abuse, tick-borne illness, and TB, demonstrating the breadth of possibilities that must be considered during the diagnostic process.[2][8]

Prognosis

The prognosis of aseptic meningitis depends on the patient's age and the condition's etiology.[7] Viral meningitis typically follows a benign course, and most patients experience a complete recovery within 5 to 14 days. Residual symptoms are usually limited to fatigue and lightheadedness in most cases.[2]

Other viruses and nonviral causes of meningitis, including the herpes viruses, may not be as benign a course.[2] TB meningitis is complicated, carrying a high risk of morbidity and mortality if not promptly diagnosed and treated.[2][7]

Complications

Aseptic meningitis can lead to complications such as seizures, and in severe cases, it can progress to status epilepticus. While this complication necessitates treatment, prevention is not typically recommended.[2] In cases where bacterial meningitis is suspected and treatment is delayed, there is a risk of permanent neurological sequelae, including hearing loss.[2][7]

Encephalitis may co-occur with viral meningitis, leading to a variable clinical presentation. Mumps meningoencephalitis, for example, can cause sensorineural deafness and aqueductal stenosis, which may result in hydrocephalus. In the case of TB meningitis, complications include hydrocephalus, infarcts, epilepsy, mental regression, neurological deficits, and cranial nerve palsies.[2][7]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Following the initial diagnosis and treatment, the paramount objective is to curb the spread of highly infectious agents. Strict isolation protocols, often involving droplet precautions, and frequent hand washing are crucial to controlling the transmission of viral meningitis and many other infectious causes. Special attention, especially after diaper changes in children, is necessary to prevent the spread of enterovirus infections.[2][7]

Proper hand hygiene is essential, and isolation measures should be implemented based on the suspected cause of the infection. Vaccination is a crucial preventive measure, with vaccines available for those at risk of polio, mumps, measles, mumps varicella, and rubella. These vaccines should be administered according to the recommended vaccine schedule. Additionally, arboviral vaccines are available as a precautionary measure for populations residing in or traveling to endemic areas.[2][8][7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In managing aseptic meningitis, a team-based approach is essential. Physicians diagnose the condition based on clinical symptoms and lab results, determining appropriate treatment strategies, medications, and hospitalization when necessary. Effective communication with patients and their families is crucial to ensure they comprehend the diagnosis, treatment plan, and expectations.

In managing aseptic meningitis, the primary focus is supportive care, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate medical treatment. Specialists in fields such as infectious disease and neurology can be involved, especially in cases where the patient exhibits severe neurological symptoms and complications or requires specialized assessments. An oncologist may also be helpful if meningitis is due to malignancy.

Because meningitis represents a dangerous infectious disease, communication with all levels of the staff is essential. Ensuring the proper isolation measures and using personal protective equipment (PPE) to prevent the spread of the infection to the medical team or other patients is paramount and should be of primary concern. Once the diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is established and more concerning diagnoses are excluded, these precautions can be discontinued.[2][7]

An LP is necessary to confirm the diagnosis and can be conducted by an emergency medicine clinician, an internist on an inpatient floor, or an interventional radiologist. Laboratory proficiency is essential to analyze specimens and conduct PCR studies, aiding in identifying the most common etiology, typically viruses. Unfortunately, these studies are still underutilized.[2][4][7]

Nurses closely monitor patients, observing vital signs and neurological status, which is crucial for early detection of complications or deterioration. Pharmacists collaborate with healthcare providers to ensure appropriate dosages, interactions, and compatibility of medications prescribed for aseptic meningitis.

Regular interprofessional team meetings facilitate discussions about patient progress, adjustments to the treatment plan, and addressing any challenges faced by the healthcare team.[2][4][7][8] Coordination between hospital and community-based care ensures a seamless patient transition, preventing gaps in follow-up appointments and medication adherence.