Continuing Education Activity

Neisseria meningitidis is a gram-negative bacterium that inhabits the mucosal surface of the nasopharynx in approximately 10% of healthy persons. The invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is a severe form of Neisseria meningitidis infection, most commonly manifested as meningitis or septicemia. Initially, non-specific symptoms of infection with fever often lead to a rapid deterioration of the patient's condition and death within 12 to 24 hours of the onset of the disease. This activity reviews Neisseria meningitidis as a disease and discusses the role of the interprofessional team in educating patients on the need for meningococcal prophylaxis and the options available.

Objectives:

- Identify the global health burden of meningococcal disease.

- Describe the modalities available for post-exposure chemoprophylaxis of meningococcal disease.

- Review the indications for meningococcal meningitis prophylaxis.

- Explain the features of Neisseria meningitidis as a disease and discuss the need for meningococcal prophylaxis.

Introduction

Neisseria meningitidis is a gram-negative bacterium that inhabits the mucosal surface of the nasopharynx in approximately 10% of healthy persons. The invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is a severe form of Neisseria meningitidis infection, most commonly manifested as meningitis or septicemia. Initially, non-specific symptoms of infection with fever often lead to a rapid deterioration of the patient's condition and death within 12 to 24 hours of the onset of the disease. The infection may occur in the form of sporadic, epidemic, or pandemic disease. The incidence of IMD is estimated at 0.3 to 3/100,000 residents in developed countries,[1] reaching up to 10 to 25/100,000 in some less developed countries.[2] The prevalence of IMD peaks among persons in three age groups: infants and children aged younger than 5 years (the incidence in infants aged younger than 1 year reaches 2.6 cases per 100,000), adolescents and young adults aged 16 to 21 years (0.4 cases per 100,000), and people 65 years of age (0.3 cases per 100,000).[3] Approximately 5% to 20% of IMD cases occur as sepsis, with high mortality of up to 20% to 80%.[4][2] Meningococcal meningitis results in a lower rate of morbidity of 55 to 18%.[5] Nonetheless, 11 to 19% of survivors experience serious sequelae (e.g., neurologic disability, limb loss, and hearing loss).[6]

The diversity of capsular antigens on the surface of the bacteria allowed the distinction of 12 serotypes of N. meningitidis. Types A, B, C, Y, W are responsible for more than 90% of IMD cases globally. Serogroup B leads to approximately 60% of disease among children aged younger than 5 years, while serogroups C, Y, or W cause 73% of IMD cases in a group of persons aged equal to 11 years.[3] Types A and C are responsible for most epidemic outbreaks, while infection with type B usually occurs as a sporadic disease. N. meningitidis is spread through droplets from the upper respiratory tract of colonized individuals (saliva and other respiratory secretions during coughing, sneezing, kissing, and chewing on toys), both by patients affected by the disease and also the asymptomatic carriers of bacteria.

The great burden of the disease has led to the implementation of various strategies to prevent IMD.

Issues of Concern

Meningococcal Vaccination

Meningococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine

There are three types of meningococcal vaccines. The oldest vaccine is a polysaccharide containing fragments of the meningococcal polysaccharide capsule of four serotypes as antigens (MPSV4). These vaccines are characterized by low immunogenicity in children, so they should not be used for primary immunization in patients younger than 5 years. They are effective as booster doses after vaccination with a conjugate vaccine.[3]

Meningococcal C Conjugate Vaccines (MenCC)

The conjugated vaccines, similarly like polysaccharide one, contains fragments of the N. meningitidis capsule antigens, although they are linked to a protein that is most often a tetanus toxin (MenACWY-D) or a genetically modified diphtheria toxin (MenACWY-CRM). This combination makes these vaccines immunogenic even in the youngest infants. They effectively generate immunological memory and reduce the nasopharyngeal carriage.[7] Currently available conjugated vaccines are designed as monovalent ones against serogroup C, bivalent against serogroups C and Y, or quadrivalent vaccine against types C, A, W, and Y.

The recommendations on MenCC vaccine use vary in different regions. The first country to implement a routine MenCC vaccination into their national childhood immunization program was the United Kingdom in 1999, then followed by other European countries. The routine campaign in the United Kingdom was directed to infants (first dose at 2 months of age), but catch-up programs for other age groups led rapidly to high coverage in all persons in a group aged 2 months to 22 years. Public MenCC vaccination contributed to a reduction in serogroup C nasopharyngeal carriage and reduction of N. meningitidis type C IMD in unvaccinated age groups (herd protection).[7][8] In the United States, the vaccine was licensed in 2005 and is routinely recommended for adolescents and those at high risk of developing IMD.[3]

Numerous studies have confirmed the efficacy of the meningococcal C conjugate vaccines. In a large epidemiological study conducted in Europe from 2004 through 2014, a significant decrease in IMD prevalence was observed in countries with established MenCC vaccination programs. In countries that had introduced routine MenCC vaccines into their national vaccination program before 2004 and between 2004 and 2014, an annual decrease of 10.2% and 8.3%, respectively, was observed. No significant trend was observed in countries with no routine MenCC vaccination.[9] According to the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) surveillance of invasive bacterial disease in Europe 2008/2009, the incidence of serogroup C IMD is substantially lower in countries with MenCC vaccine included in their vaccination schedule than in countries with no established MenCC vaccination program: 0.54 vs. 1.01/100 000 among infants, 0.22 vs. 0.45/100 000 in toddlers, 0.17 vs. 0.29/100 000 in adolescents.

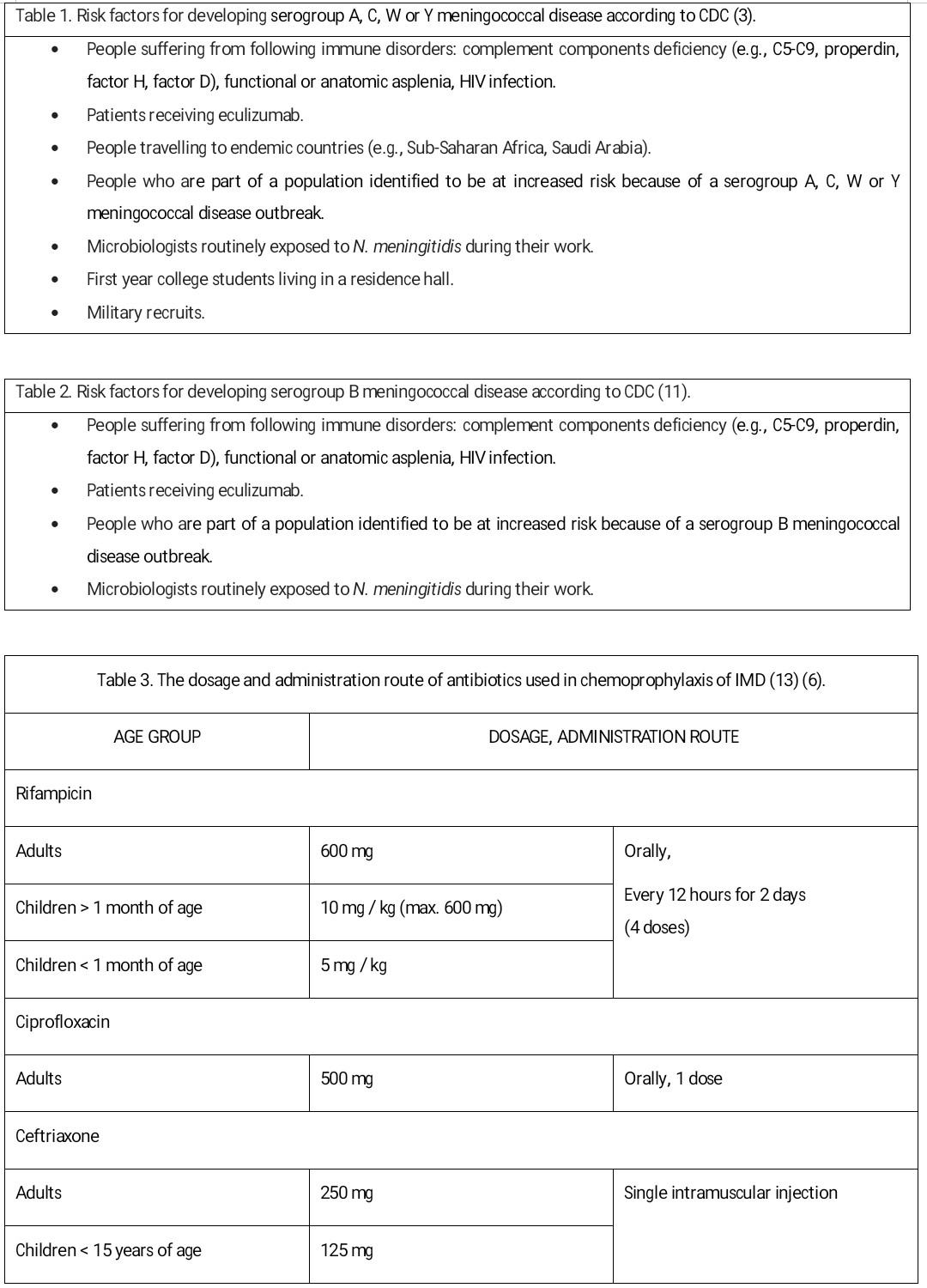

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Recommendations on Meningococcal C Conjugate Vaccine[3]

According to the CDC, all children aged 11 to 12 should be vaccinated with one dose of a conjugate meningococcal vaccine. Since protection wanes, whose vaccinated before 16 years of age require a booster dose administered with an interval of a minimum of 8 weeks, preferably at the age of 16 to 18 years. If the first dose was introduced in a person older than 16 years, the booster dose is not recommended.

Although routine vaccination of infants and young children is not recommended, all patients aged 2 months to 10 years should receive the conjugate vaccine if they belong to a high-risk group of developing IMD.

Adults should receive a conjugate meningococcal vaccine if they meet risk factors. For healthy individuals, one-dose vaccination is scheduled. For patients suffering from congenital or acquired immune deficiency (e.g., anatomical or functional asplenia, HIV infection, persistent complement component deficiency, eculizumab use), two doses of primary vaccination implemented with an 8-week interval are recommended. If the risk remains, both groups should receive the booster dose of the same preparation every 5 years.[3]

Meningococcal conjugate vaccines may be given to pregnant women who are at increased risk for meningococcal disease.[3]

Meningococcal B Protein Vaccine (MenB)

The third meningococcal vaccine group includes protein vaccines designed against group B meningococci. They are characterized by good immunogenicity; however, no data is available concerning how long their effectiveness persists due to the relatively short time of their use. In Europe, it was licensed in 2013. Since 2015, MenB vaccination had been included in the United Kingdom national childhood vaccination schedule; subsequently, other countries, including Ireland and Italy, followed. It is not publicly funded but strongly recommended in most of the other European countries. The quadrivalent MenB vaccine has been proved to produce a good immune response in children older than 2 months.[10] In 2017, the ECDC expert group considered infants under 1 year of age as the primary target group for MenB vaccination. In the United States, MenB vaccination is recommended for adolescents and adults at a high risk of serogroup B IMD (see CDC recommendations below).[3]

CDC Recommendations on Meningococcal B vaccine[3]

MenB vaccines are recommended for adolescents aged 10 and older belonging to the risk factors group. The preferred age for MenB vaccination is 16 to 18 years.[11] The full primary vaccination consists of two or three doses, depending on the preparation. The preparations are interchangeable, and the same product must be used for all doses.

As there are no randomized controlled trials concerning the safety of MenB vaccines, use in pregnant or lactation women, the vaccination may be implemented only in case of increased risk of developing B-type meningococcal disease when the potential benefits outweigh the risks.[11]

Clinical Significance

Chemoprophylaxis of Invasive Meningococcal Disease

As the meningococcal infection spreads with droplets, the disease is a serious threat for both the patient and close contacts. The risk of developing the disease for household contacts exposed to patients who have sporadic meningococcal disease was estimated to be 4:1000 exposed people, which is 500 to 800 times greater than the risk for the total population.[6] The risk for health care providers exposed to infected patients is 25 times higher than for a general population.[12] Chemoprophylaxis aims to prevent the illness among close contacts.

Indications

Following CDC recommendations, the strategy of meningococcal prophylaxis should be implemented within 24 hours after contact or identification of the pathogen. In cases of a delayed report of IMD, the realization of chemoprophylaxis is reasoned up to 14 days from the disease onset.[6] The decision about chemoprophylaxis implementation should not be based on nasopharyngeal culture.

The indications for chemoprophylaxis implementation are as follows.[6]

- Close contact with a patient within 7 days before the disease onset, regardless of vaccination status. "Close contact" applies to:

- Household members living with a sick person

- People who are in intimate contact with the patient

- People sleeping in the same bedroom with the patient (students, soldiers, officers)

- People who have been in direct contact with secretions from the patient's respiratory tract during medical procedures, including mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, suctioning, and endotracheal intubation, before or less than 24 hours after antimicrobial therapy was initiated

- People traveling with the patient in the same plane, ship, bus, or car for longer than 8 hours

- The patient himself before discharge from a hospital if they were not treated with ceftriaxone.

Drinking from the same bottle, using the same cutlery, or smoking the same cigarette, is not an indication of the implementation of prophylaxis unless there is an additional risk of close contact described above.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics effective in eliminating the carriage of N. meningitidis, therefore recommended in chemoprophylaxis of IMD are rifampicin, ciprofloxacin, and ceftriaxone.[13]

Rifampicin

Rifampicin can be used in every age group. Contraindications to its use include pregnancy, jaundice, and hypersensitivity to the drug. Rifampicin is the most powerful known inducer of the hepatic cytochrome P450enzyme system, therefore increases the metabolism of many drugs. Patients undergoing long-term anticoagulation therapy with warfarin have to increase their dosage and have their clotting time frequently checked because failure to do so could lead to inadequate anticoagulation, resulting in serious consequences of thromboembolism. Rifampicin can reduce the efficacy of birth control pills or other hormonal contraception. Patients receiving rifampicin should be informed of the possibility of side effects such as urine, stool, sweat, or tears discolor in red or orange.[13]

Ciprofloxacin

Ciprofloxacin is intended for use only in adults (older than 18 years of age). It is contraindicated in children, pregnant women, and nursing mothers.[13]

Ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone may be used in every age group, although the intramuscular route of administration makes it less convenient. Ceftriaxone is a first-line antibiotic recommended as chemoprophylaxis of IMD in pregnancy and nursing mothers.[13]

Azithromycin

The effectiveness of azithromycin in eliminating the nasopharyngeal carriage of N. meningitidis has been proven in only one study in adults.[14] According to AAP, azithromycin can be used for chemoprophylaxis, where ciprofloxacin resistance has been detected.

Some regions have documented resistance of N. meningitidis to ciprofloxacin or rifampicin.[13] Local societies should update their recommendations of antibiotics used in IMD chemoprophylaxis based on regional resistance data. Although the presented chemoprophylaxis effectiveness reaches up to 90% to 95%, it does not provide 100% protection against the disease. Patients who have received antibiotic therapy should be informed about the symptoms of the meningococcal disease and the need to report to the hospital instantly in case they occur.

Post-Exposure Immunoprophylaxis

A secondary case can occur several weeks after the index one; therefore, a meningococcal vaccine is a supporting strategy in meningococcal prophylaxis. In outbreaks caused by serogroups A, C, Y, and W, local authorities should decide on mass vaccination campaigns.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All primary caregivers must be familiar with vaccination guidelines. An interprofessional approach is best to improve vaccination rates and post-exposure prophylaxis. This team includes physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. If there is any doubt about vaccination against N. meningitides, an infectious disease consultation is highly recommended.