[1]

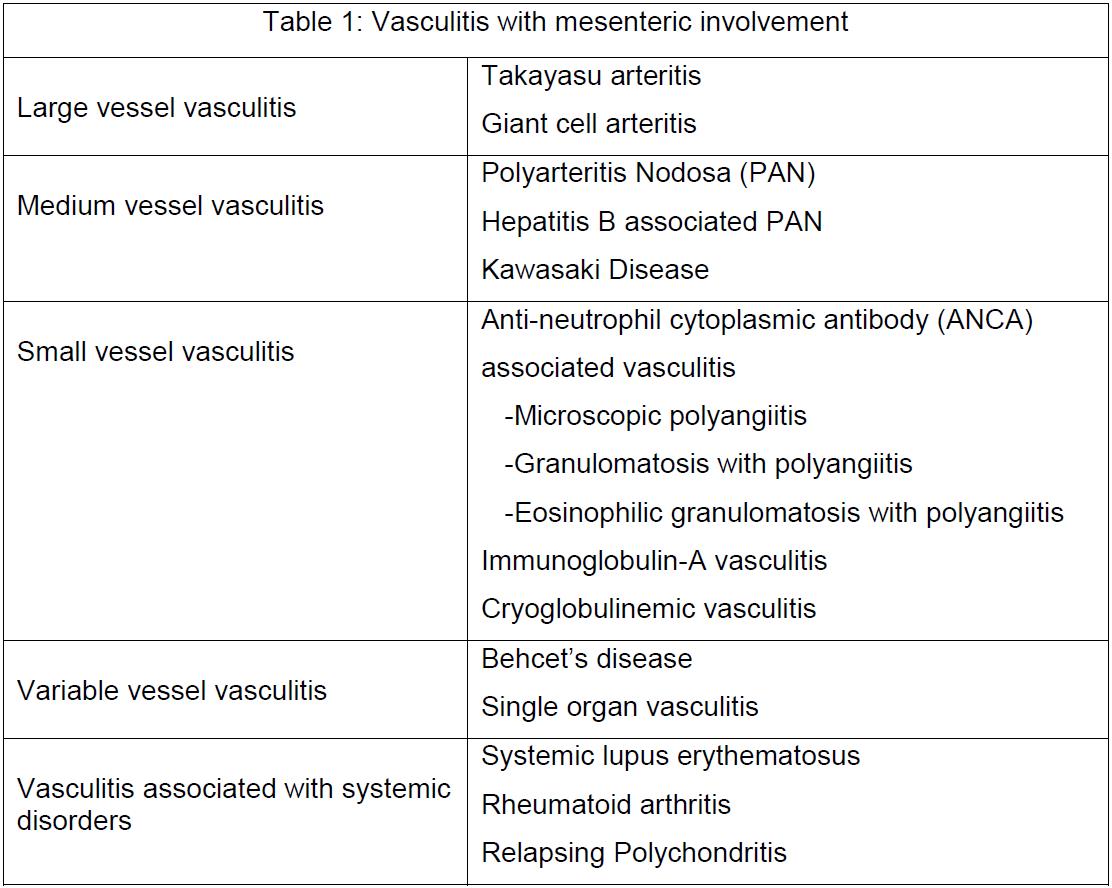

Koster MJ, Warrington KJ. Vasculitis of the mesenteric circulation. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology. 2017 Feb:31(1):85-96. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.12.003. Epub 2017 Jan 5

[PubMed PMID: 28395792]

[2]

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, Flores-Suarez LF, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Jayne DR, Kallenberg CG, Lamprecht P, Langford CA, Luqmani RA, Mahr AD, Matteson EL, Merkel PA, Ozen S, Pusey CD, Rasmussen N, Rees AJ, Scott DG, Specks U, Stone JH, Takahashi K, Watts RA. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013 Jan:65(1):1-11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23045170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Watts RA, Robson J. Introduction, epidemiology and classification of vasculitis. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology. 2018 Feb:32(1):3-20. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2018.10.003. Epub 2018 Nov 16

[PubMed PMID: 30526896]

[4]

Watts RA,Scott DG, Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2003 Jan;

[PubMed PMID: 12496504]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[5]

Watts RA, Lane S, Scott DG. What is known about the epidemiology of the vasculitides? Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology. 2005 Apr:19(2):191-207

[PubMed PMID: 15857791]

[6]

Sharma A, Sharma K. Hepatotropic viral infection associated systemic vasculitides-hepatitis B virus associated polyarteritis nodosa and hepatitis C virus associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology. 2013 Sep:3(3):204-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.06.001. Epub 2013 Jul 8

[PubMed PMID: 25755502]

[7]

Zhou Q, Yang D, Ombrello AK, Zavialov AV, Toro C, Zavialov AV, Stone DL, Chae JJ, Rosenzweig SD, Bishop K, Barron KS, Kuehn HS, Hoffmann P, Negro A, Tsai WL, Cowen EW, Pei W, Milner JD, Silvin C, Heller T, Chin DT, Patronas NJ, Barber JS, Lee CC, Wood GM, Ling A, Kelly SJ, Kleiner DE, Mullikin JC, Ganson NJ, Kong HH, Hambleton S, Candotti F, Quezado MM, Calvo KR, Alao H, Barham BK, Jones A, Meschia JF, Worrall BB, Kasner SE, Rich SS, Goldbach-Mansky R, Abinun M, Chalom E, Gotte AC, Punaro M, Pascual V, Verbsky JW, Torgerson TR, Singer NG, Gershon TR, Ozen S, Karadag O, Fleisher TA, Remmers EF, Burgess SM, Moir SL, Gadina M, Sood R, Hershfield MS, Boehm M, Kastner DL, Aksentijevich I. Early-onset stroke and vasculopathy associated with mutations in ADA2. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Mar 6:370(10):911-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307361. Epub 2014 Feb 19

[PubMed PMID: 24552284]

[8]

Navon Elkan P, Pierce SB, Segel R, Walsh T, Barash J, Padeh S, Zlotogorski A, Berkun Y, Press JJ, Mukamel M, Voth I, Hashkes PJ, Harel L, Hoffer V, Ling E, Yalcinkaya F, Kasapcopur O, Lee MK, Klevit RE, Renbaum P, Weinberg-Shukron A, Sener EF, Schormair B, Zeligson S, Marek-Yagel D, Strom TM, Shohat M, Singer A, Rubinow A, Pras E, Winkelmann J, Tekin M, Anikster Y, King MC, Levy-Lahad E. Mutant adenosine deaminase 2 in a polyarteritis nodosa vasculopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Mar 6:370(10):921-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307362. Epub 2014 Feb 19

[PubMed PMID: 24552285]

[9]

Camilleri M, Pusey CD, Chadwick VS, Rees AJ. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic vasculitis. The Quarterly journal of medicine. 1983 Spring:52(206):141-9

[PubMed PMID: 6604292]

[10]

Oldenburg WA, Lau LL, Rodenberg TJ, Edmonds HJ, Burger CD. Acute mesenteric ischemia: a clinical review. Archives of internal medicine. 2004 May 24:164(10):1054-62

[PubMed PMID: 15159262]

[11]

Ebert EC, Hagspiel KD, Nagar M, Schlesinger N. Gastrointestinal involvement in polyarteritis nodosa. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2008 Sep:6(9):960-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.004. Epub 2008 Jun 27

[PubMed PMID: 18585977]

[12]

Gnanapandithan K, Feuerstadt P. Review Article: Mesenteric Ischemia. Current gastroenterology reports. 2020 Mar 17:22(4):17. doi: 10.1007/s11894-020-0754-x. Epub 2020 Mar 17

[PubMed PMID: 32185509]

[13]

Human A, Pagnoux C. Diagnosis and management of ADA2 deficient polyarteritis nodosa. International journal of rheumatic diseases. 2019 Jan:22 Suppl 1():69-77. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13283. Epub 2018 Apr 6

[PubMed PMID: 29624883]

[14]

Ha HK, Lee SH, Rha SE, Kim JH, Byun JY, Lim HK, Chung JW, Kim JG, Kim PN, Lee MG, Auh YH. Radiologic features of vasculitis involving the gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2000 May-Jun:20(3):779-94

[PubMed PMID: 10835128]

[15]

Angle JF, Nida BA, Matsumoto AH. Managing mesenteric vasculitis. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2015 Mar:18(1):38-42. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.12.006. Epub 2014 Dec 29

[PubMed PMID: 25814202]

[16]

Rits Y, Oderich GS, Bower TC, Miller DV, Cooper L, Ricotta JJ 2nd, Kalra M, Gloviczki P. Interventions for mesenteric vasculitis. Journal of vascular surgery. 2010 Feb:51(2):392-400.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.082. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20141962]

[17]

Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, Mahr A, Cohen P, Le Guern V, Bienvenu B, Mouthon L, Guillevin L, French Vasculitis Study Group. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: a systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group Database. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010 Feb:62(2):616-26. doi: 10.1002/art.27240. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20112401]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[18]

Stanson AW, Friese JL, Johnson CM, McKusick MA, Breen JF, Sabater EA, Andrews JC. Polyarteritis nodosa: spectrum of angiographic findings. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2001 Jan-Feb:21(1):151-9

[PubMed PMID: 11158650]

[19]

Steele C, Bohra S, Broe P, Murray FE. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage and colitis: an unusual presentation of Wegener's granulomatosis. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2001 Aug:13(8):993-5

[PubMed PMID: 11507371]

[20]

Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, Kallenberg CG, St Clair EW, Turkiewicz A, Tchao NK, Webber L, Ding L, Sejismundo LP, Mieras K, Weitzenkamp D, Ikle D, Seyfert-Margolis V, Mueller M, Brunetta P, Allen NB, Fervenza FC, Geetha D, Keogh KA, Kissin EY, Monach PA, Peikert T, Stegeman C, Ytterberg SR, Specks U, RAVE-ITN Research Group. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Jul 15:363(3):221-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20647199]

[21]

Salvarani C, Calamia KT, Crowson CS, Miller DV, Broadwell AW, Hunder GG, Matteson EL, Warrington KJ. Localized vasculitis of the gastrointestinal tract: a case series. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2010 Jul:49(7):1326-35. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq093. Epub 2010 Apr 1

[PubMed PMID: 20360040]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[22]

Setty HS, Rao M, Srinivas KH, Srinivas BC, Usha MK, Jayaranganath M, Patil SS, Manjunath CN. Clinical, angiographic profile and percutaneous endovascular management of Takayasu's arteritis - A single centre experience. International journal of cardiology. 2016 Oct 1:220():924-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.194. Epub 2016 Jun 26

[PubMed PMID: 27420344]

[23]

Hisamatsu T, Ueno F, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi K, Koganei K, Kunisaki R, Hirai F, Nagahori M, Matsushita M, Kobayashi K, Kishimoto M, Takeno M, Tanaka M, Inoue N, Hibi T. The 2nd edition of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet's disease: indication of anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies. Journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Jan:49(1):156-62. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0872-4. Epub 2013 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 23955155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[24]

Tian XP, Zhang X. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: insight into pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology. 2010 Jun 28:16(24):2971-7

[PubMed PMID: 20572299]

[25]

Yuan S, Ye Y, Chen D, Qiu Q, Zhan Z, Lian F, Li H, Liang L, Xu H, Yang X. Lupus mesenteric vasculitis: clinical features and associated factors for the recurrence and prognosis of disease. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2014 Jun:43(6):759-66. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.005. Epub 2013 Nov 12

[PubMed PMID: 24332116]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[26]

Ko SF, Lee TY, Cheng TT, Ng SH, Lai HM, Cheng YF, Tsai CC. CT findings at lupus mesenteric vasculitis. Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987). 1997 Jan:38(1):115-20

[PubMed PMID: 9059413]

[27]

Puéchal X, Gottenberg JE, Berthelot JM, Gossec L, Meyer O, Morel J, Wendling D, de Bandt M, Houvenagel E, Jamard B, Lequerré T, Morel G, Richette P, Sellam J, Guillevin L, Mariette X, Investigators of the AutoImmunity Rituximab Registry. Rituximab therapy for systemic vasculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the AutoImmunity and Rituximab Registry. Arthritis care & research. 2012 Mar:64(3):331-9. doi: 10.1002/acr.20689. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22076726]

[28]

Scola CJ, Li C, Upchurch KS. Mesenteric involvement in giant cell arteritis. An underrecognized complication? Analysis of a case series with clinicoanatomic correlation. Medicine. 2008 Jan:87(1):45-51. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181646118. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18204370]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[29]

Sharma A, Gnanapandithan K, Sharma K, Sharma S. Relapsing polychondritis: a review. Clinical rheumatology. 2013 Nov:32(11):1575-83. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2328-x. Epub 2013 Jul 26

[PubMed PMID: 23887438]

[30]

Colomba C, La Placa S, Saporito L, Corsello G, Ciccia F, Medaglia A, Romanin B, Serra N, Di Carlo P, Cascio A. Intestinal Involvement in Kawasaki Disease. The Journal of pediatrics. 2018 Nov:202():186-193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.06.034. Epub 2018 Jul 17

[PubMed PMID: 30029859]