Continuing Education Activity

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by chronic inflammation, demyelination, gliosis, and neuronal loss. The course may be relapsing-remitting or progressive in nature. Lesions in the CNS occur at different times and in different CNS locations. Because of this, multiple sclerosis lesions are sometimes said to be "disseminated in time and space." The clinical course of the disease is quite variable, ranging from stable chronic disease to a rapidly evolving and debilitating illness. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis of MS and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Explain the pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis.

- Describe the typical presentations of multiple sclerosis.

- Summarize the workup of a patient suspected of having multiple sclerosis.

- Review the need for enhanced coordination of care among interprofessional teams to improve outcomes for patients affected by multiple sclerosis.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by inflammation, demyelination, gliosis, and neuronal loss.[1] Pathologically, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, and macrophages produce degradation of myelin sheaths that surround neurons. Neurological symptoms vary and can include vision impairment, numbness and tingling, focal weakness, bladder and bowel incontinence, and cognitive dysfunction. Symptoms vary depending on lesion location. Clinical symptoms characterized by acute relapses typically first develop in young adults. A gradually progressive course then ensues with permanent disability in 10 to 15 years.[2]

MS groups into seven categories based on disease course:

1) Relapsing-remitting (RR): 70 to 80% of MS patients demonstrate an initial onset characterized by a relapsing-remitting (RR) course, demonstrating the following neurologic presentation:

- New or recurrent neurological symptoms consistent with MS

- Symptoms last 24 to 48 hours

- They develop over days to weeks

2) Primary progressive (PP): 15 to 20% of patients present with a gradual deterioration from the onset, with an absence of relapses.

3) Secondary progressive (SP): this is characterized by a more gradual neurologic deterioration after an initial RR course. Superimposed relapses can be a feature of this clinical course, as well, although this is not a mandatory feature.

4) Progressive-relapsing (PR) MS: in 5% of patients, a gradual deterioration with superimposed relapses occurs.

The following three categories are sometimes included in the spectrum of MS:

5) Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS): often classified as a single episode of inflammatory CNS demyelination.

6) Fulminant: characterized by severe MS with multiple relapses and rapid progression towards disability.

7) Benign: a clinical course characterized by an overall mild disability. Relapses are rare.

When discussing MS, clinicians most often describe the RR course, considering its high prevalence amongst affected patients. Relapses often recover either partially or completely over weeks and months, frequently without treatment. Over time, residual symptoms from relapses without complete recovery accumulate and contribute to general disability. The diagnosis of RR MS is made with at least two CNS inflammatory events. Although different diagnostic criteria have been used for MS, the general principle of diagnosing the RR course has involved establishing episodes separated in "time and space."[3] This means that episodes must be separated in time and affect different locations of the CNS. Making the diagnosis of MS expeditiously allows for the early and effective institution of disease-modifying therapy.[1] Treatment aims at decreasing relapses and MRI activity. Long-term therapy aims at reducing the risk of permanent disability.

Etiology

The exact etiology of MS is unknown. Factors involved in pathogenesis broadly group into three categories:

- Immune factors

- Environmental factors

- Genetic associations

Dysimmunity with an autoimmune attack on the central nervous system is the leading hypothesized etiology of MS. Although there are various proposed hypothetical mechanisms, the postulated “out-side-in” mechanism involves CD4+ proinflammatory T cells.[4] Researchers hypothesize that an unknown antigen triggers and activates both Th1 and Th17, leading to CNS endothelium attachment, the crossing of the blood-brain barrier, and subsequent immune attack through cross-reactivity. The “inside-out” hypothesis suggests an intrinsic CNS abnormality that triggers and results in inflammatory-mediated tissue damage.[4]

Environmental factors, including latitudinal gradients in different countries, have been well-studied phenomena.[5] Vitamin D deficiency has been considered a possible etiology for the noted predisposition of the population in higher latitudes being affected.[6] Different infections, including Epstein Barr virus (EBV), may also play a role.[7] There are likely complex interactions between various environmental factors with patient genetics, and understanding these pathways is an area of ongoing research.

There is a high risk of MS in patients with biological relatives with MS. Heritability is estimated to be between 35 and 75%.[8] Monozygotic twins have a concordance rate of 20 to 30%, while dizygotic twins have a concordance rate of 5%.[9] There is a 2% concordance in parents and children, and this is still 10 to 20 fold higher risk than in the general population.[10] The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DRB1*1501 has a strong correlation with multiple sclerosis and is one of the most studied alleles relative to MS linkage.[11] To date, there is no defined Mendelian form of genetic occurrence, and implications point to numerous genes.[12]

Epidemiology

Approximately 400,000 individuals in the United States and 2.5 million individuals worldwide have multiple sclerosis.[13] The disease is three-fold more common in females than in males.[13] While the age of onset is usually between 20 to 40 years, the disease can present at any age. Almost 10% of the cases present before the age of 18.[14] An overall prevalence of 1 in 1000 is cited for populations of European ancestry.[15] Less is understood about the prevalence in non-European populations, and most data suggests lower prevalence in those of East Asian and African descent.[16] Recent studies have noted a high prevalence in African-American populations, similar to that of European ancestry.[16]

MS demonstrates a prevalence based on latitude gradient with increased prevalence in northern latitudes of Europe and North America. Observations noting variable genetic susceptibility factors amongst different human subpopulations apart from latitude have also been documented, suggesting poorly understood genetic factors interacting with environmental ones. Various studies have noted that populations that migrate to areas of greater MS prevalence during childhood also adopt a higher risk of acquiring MS.[17] Other studies have called this observation into question.[18] Neither genetic or exogenous risk factors can independently explain the epidemiological observations of MS.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of MS is limited to the primary CNS. Two fundamental processes constitute general pathological process seen in MS patients:

- Focal inflammation resulting in macroscopic plaques and injury to the blood-brain barrier (BBB)

- Neurodegeneration with microscopic injury involving different components of the CNS including axons, neurons, and synapse

Together, these two primary processes result in macroscopic and microscopic injury. Lesions referred to as plaques occur in waves throughout the disease course and result from focal inflammation. MS plaques predominantly center around small veins and venules and show sharp margins. Myelin loss, edema, and axonal injury are the chief components of plaque pathology. BBB disruption during active plaque inflammation corresponds to enhancement seen on MRI. Over time, the inflammatory process subsides, resulting in an astrocytic scar.

Microscopically MS lesions show mononuclear infiltrate with perivenular cuffing and surrounding white matter infiltration. Monocytes and macrophages, which represent innate immunity, stimulate T-cell migration across the BBB. The overall net result is an injury to the BBB and the entry of systemic immune cells. Activation of microglia, the main antigen-presenting cells of the primary CNS, often precedes cell entry. CNS injury results in the initiation of cytotoxic activities of microglia with the release of nitrous oxide and other superoxide radicals. Recently, there has been a greater understanding of the critical role of B cells and antibody production in the pathogenesis of MS.[19] B cell follicles in the meninges of MS patients have been noted, with an association with early-onset MS.[20]

Histopathology

Histologically, MS plaques are characterized primarily by inflammation and myelin breakdown. Other features include neurodegeneration and oligodendrocyte injury. Multiple histologic stains are employed with adjunct immunohistochemistry aiding in diagnosis:

- Hematoxylin and eosin staining

- Myelin stains (i.e., Luxol fast blue)

- Monocyte and macrophage markers(i.e., CD68)

- Axonal and astrocyte stains

Active plaques are characterized in varying degrees by the following features:

- Extensive macrophage infiltration

- Myelin debris frequently contained within macrophages

- The presence of major myelin protein (in late active plaques)

- Perivascular inflammatory infiltrates

- Presence of lymphocytes (particularly CD8-positive cytotoxic T cells)

- Plump shaped and mitotic astrocytes

- Variable degrees of oligodendrocytes injury

- Activated microglia (particularly the peri-plaque white matter zone)

Chronic plaques characteristically demonstrate circumscribed demyelinated lesions. They occur more frequently and are characterized by the following features:

- Hypocellularity and demyelination

- Macrophages laden with myelin

- Perivascular inflammation, relatively decreased compared to active plaques

- Resolving edema

- In remyelinated plaques, there are thinly myelinated axons and axons with newly formed myelin sheaths

- The appearance of oligodendrocyte precursor cells(classically in remyelinated plaques)

History and Physical

MS presents with a broad range of symptoms reflective of the multifocal lesions of the CNS. The severity and wide range of symptoms are reflective of lesion burden, location, and degree of tissue injury. Symptoms are often not reflective of MRI evidence of active plaques given repair mechanisms and neural plasticity involved in tissue injury.

Typical clinical manifestations noted on history include:

- Vision symptom: includes vision loss(either monocular or homonymous), double vision, symptoms relating to optic neuritis.

- Vestibular symptoms: vertigo, gait imbalance

- Bulbar dysfunction: dysarthria, dysphagia

- Motor: weakness, tremor, spasticity, fatigue

- Sensory: loss of sensation, paresthesias, dysesthesias

- Urinary and bowel symptoms: incontinence, retention, urgency, constipation, diarrhea, reflux

- Cognitive symptoms: memory impairment, impairment of executive functions, trouble concentrating

- Psychiatric symptoms: depression, anxiety

The RR course of MS is observed in a majority of patients and is characterized by exacerbation and relapses of neurological symptoms, with stability between episodes. The following features generally characterize the RR course of MS:

- New or recurrent neurological symptoms

- Symptoms developing over days and weeks

- Symptoms lasting 24 to 48 hours

Symptoms from relapses frequently resolve, however over time, residual symptoms relating to episodes of exacerbation accrue. This accrual of symptoms, generally after 10 to 15 years, results in long term disability over time. Neurologic manifestations are heterogeneous in severity and degree of recovery. The secondary-progressive (SP) course is often noted in patients with RR after 10 to 15 years of onset and is characterized by a more gradual worsening of symptoms with continued progression with or without superimposed relapses. A small proportion of patients demonstrate gradual worsening of disability from onset of disease, described as the primary progressive (PP) course of MS. Myelopathy, cognitive symptoms, and visual symptoms are most frequently the clinical manifestations in this clinical course.

The physical exam mirrors evaluation of the patient's history of present illness and includes:

HEENT:

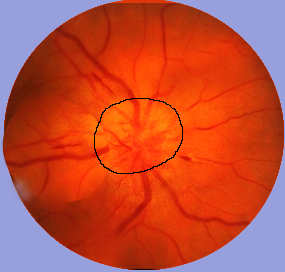

- Evaluation for optic neuritis, classically manifesting as subacute monocular central vision loss; pain on eye movement is also classically noted.

- Difficulty with adducting in lateral gaze suggesting internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO)

- Nystagmus

- Diplopia

- Hearing loss

- Facial pain

Neuromuscular/neurologic:

- Partial transverse myelitis which is typically unilateral or bilateral and characterized by sensory disturbances

- Brainstem symptoms classically involving diplopia, dysphagia, dysarthria, and ataxia

- L'hermittes sign; often described as a shock-like sensation that occurs with neck flexion

- Hyperreflexia

- Tremor

- Muscle spasms

- Weakness

Genitourinary:

- Urinary incontinence/retension(residual bladder volume evaluation)

- Erectile dysfunction (nocturnal penile tumescence stamp test if indicated)

Evaluation

No single pathognomonic test exists for the diagnosis of MS. Diagnosis is made by weighing the history and physical, MRI, evoked potentials, and CSF/blood studies and excluded other causes of the patient's symptoms. Clinically a diagnosis can be made with evidence of two or more relapses: this is possible through objective clinical evidence of two or more lesions or objective clinical evidence of one lesion with reliable historical evidence of a prior relapse. Dissemination in space (DIS) and dissemination in time(DIT) are two hallmarks of the accurate diagnosis of MS. DIS is assessed using information from the history and physical and understanding in determining the location of CNS involvement. MRI and evoked potentials have vital roles in also establishing DIS. DIT is established by charting the disease course with a thorough history and documenting the presence of multiple exacerbations. The 2010 McDonald criteria determined that DIT can be demonstrated by new lesions on a follow-up MRI when compared to a baseline scan.[21] DIS is established by noting at least one T2 lesion in two of the four following CNS sites: spinal cord, infratentorial, juxtacortical, and periventricular regions. Revisions in the 2017 McDonald criteria increased sensitivity of diagnosis by introducing oligoclonal bands in the CSF analysis as a marker for establishing DIT. Symptomatic lesions were also included as a parameter for establishing DIT and DIS, and cortical lesions to demonstrate DIS.[22]

Evoked potentials are useful to demonstrate slowed conduction indicative of subclinical involvement. Of note, these findings are often asymmetric. MRI, CSF, and blood studies are essential in ruling out other etiologies. All patients should obtain an MRI when possible. Specific blood studies to include CBC, TSH, vitamin B12, sedimentation rate, and ANA should also be obtained in all patients.

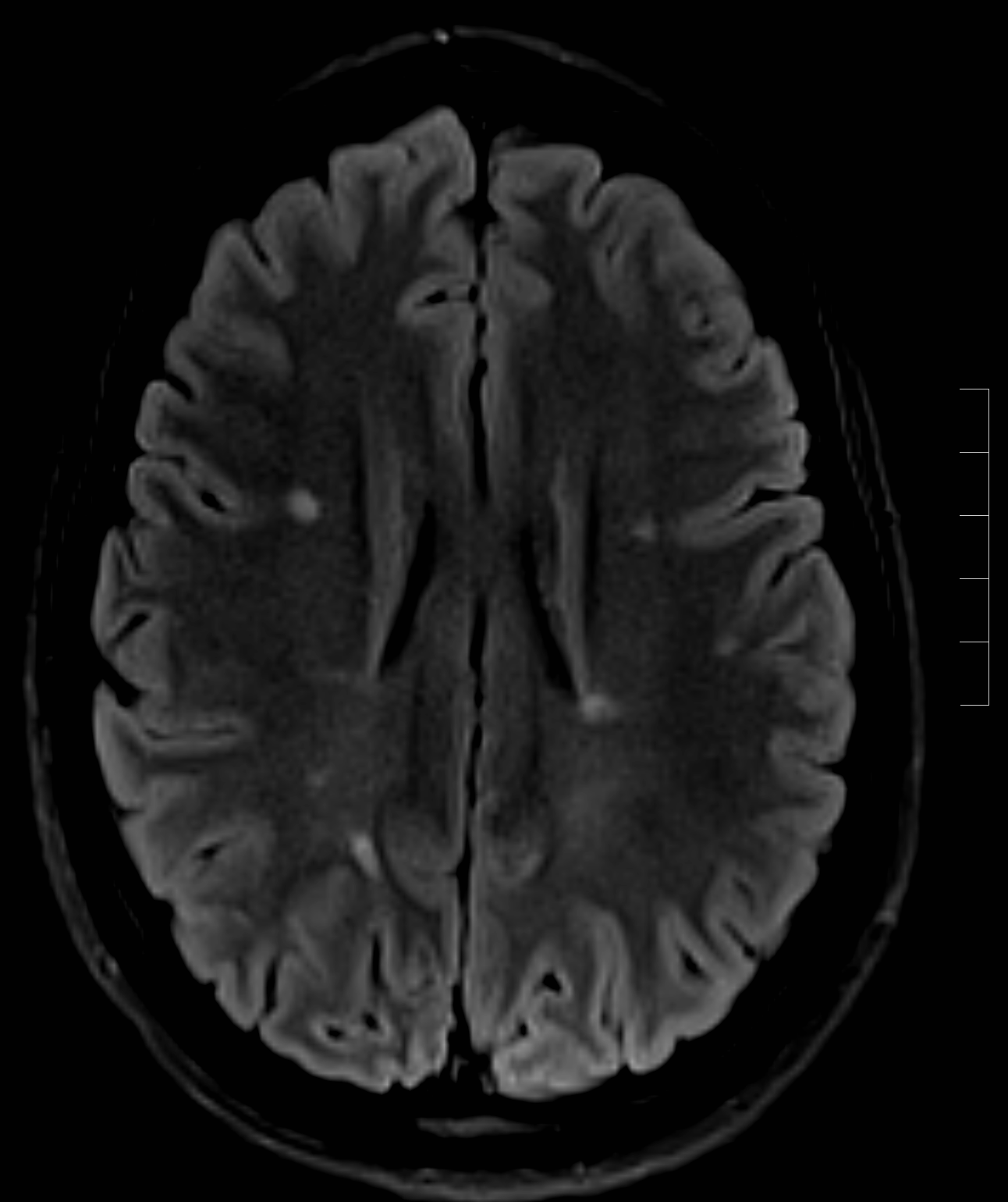

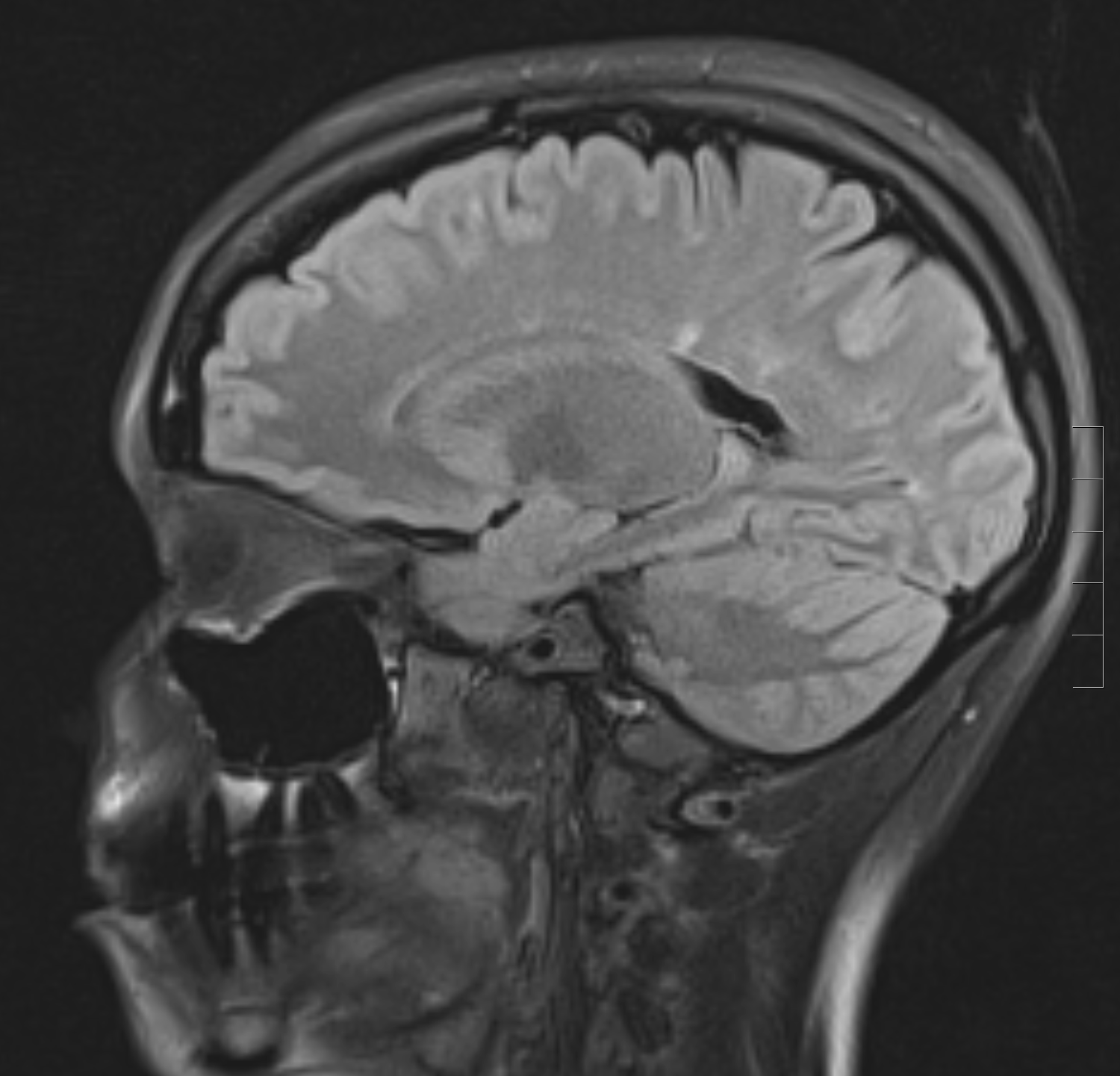

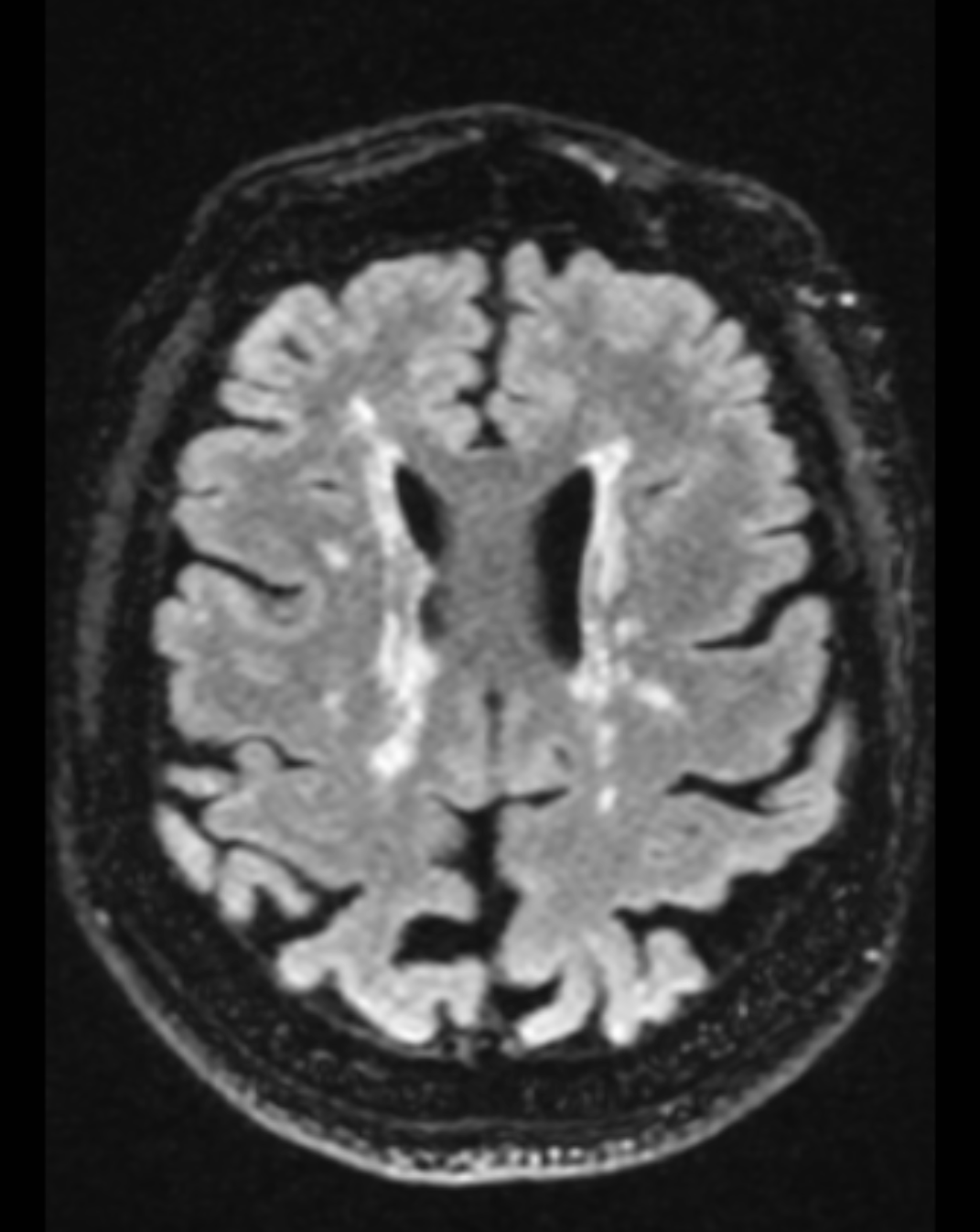

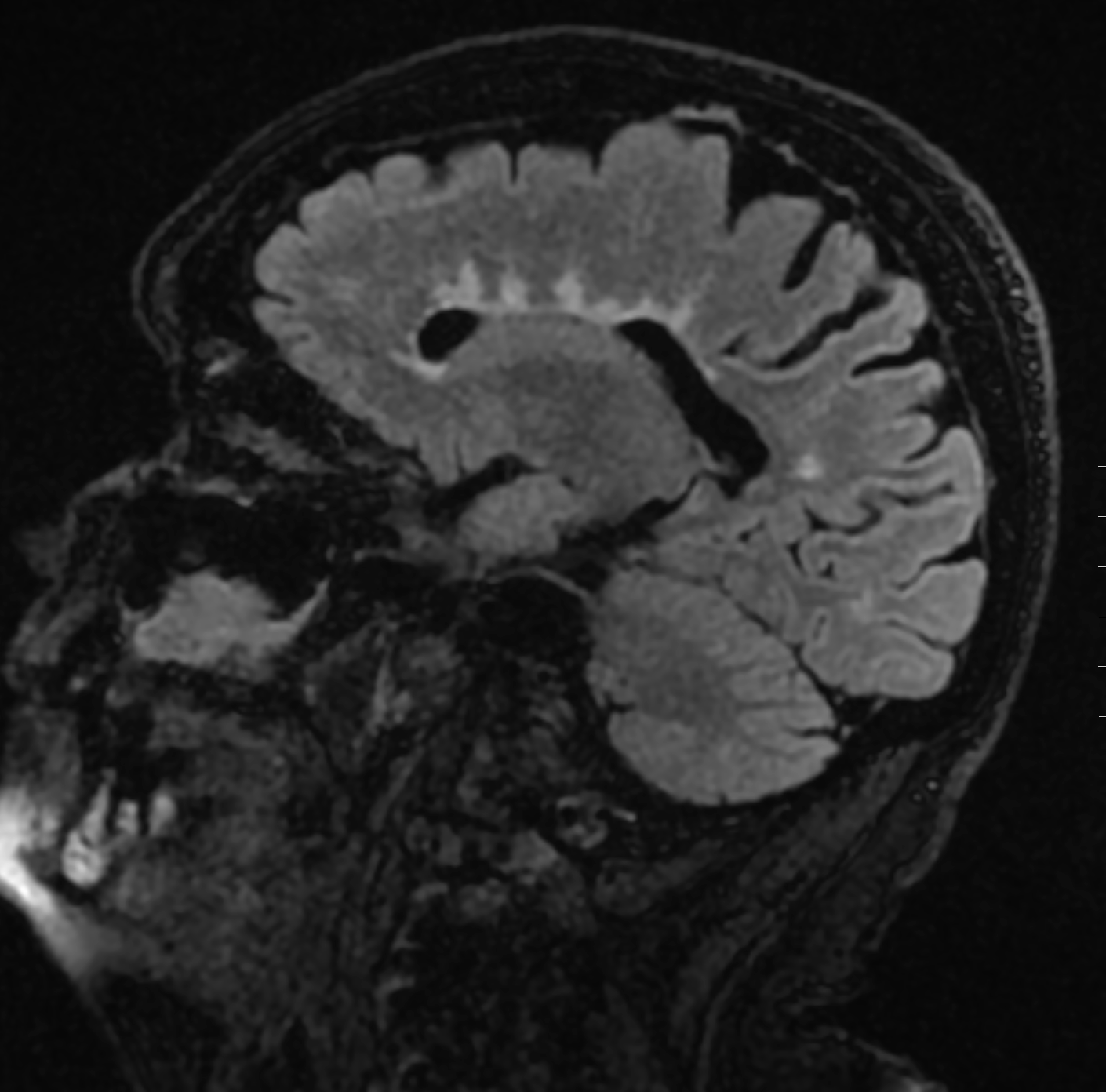

The chief characteristics of MS lesions on MRI can be summarized as the following:

- Lesions are T2 hyperintense, T1 isointense/hypointense.

- Lesions are classically oval or can be patchy.

- A high predilection for periventricular white matter

- Lesions are perpendicular to the ependymal surface(Dawson's fingers)

- Gadolinium enhancement with active lesions noted as classically diffuse or rim enhancement.

- Thinning of the corpus callosum and parenchymal atrophy

- Cord lesions classically involve the cervical or thoracic cord

The classic abnormal CSF findings in MS are as follows:

- Elevated protein and elevated myelin basic protein

- Leukocytes(occasionally seen, and typically mononuclear cells)

- Increased total IgG, increased free kappa light chains, oligoclonal bands

Treatment / Management

Disease-modifying therapies are the mainstay of treatment of relapsing-remitting MS. Glatiramer acetate, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, interferon-beta preparations, natalizumab, and mitoxantrone are some of the primary disease-modifying therapies available. Early treatment should commence upon establishing a diagnosis of MS. Short term goal includes a reduction in MRI lesion activity. Long term goals include prevention of secondary progressive MS. The primary issues after initiating therapy include patient compliance and monitoring for drug toxicity.

- Glatiramer acetate is a mixture of synthetic polypeptides, possibly functioning as a ligand for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Binding limits activation and induces regulatory cells. Possible neuroprotective and repair mechanisms are also possibilities.[23] Administration is subcutaneous. Glatiramer acetate is well tolerated; however, it is not useful for the treatment of progressive forms of MS.

- Interferon-beta preparations have various mechanisms of possible action. Interferon-beta modulates T, and B-cell function possibly alters cytokine expression, plays a role in blood-brain barrier recovery, and potentially decreases matrix metalloproteinase expression. Administration is either subcutaneous or intramuscular, depending on the preparation. Side effects include flu-like symptoms and possible brief worsening of the patient's existing neurologic symptoms.

- Natalizumab is an intravenously administered humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks leukocyte adhesion with vascular endothelial cells. This drug inhibits leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Natalizumab is usually well tolerated. Mild headaches and flushing often occur during intravenous administration.

- Mitoxantrone is an intravenously administered chemotherapeutic agent that interferes with DNA repair and RNA synthesis. A possible effect on cellular and humoral immunity may represent the mechanism of therapy for MS.[24] Different adverse effects have been documented, including amenorrhea and alopecia.

- Fingolimod is an orally administered drug with immunomodulatory effects, possibly relating to inhibition of T cell migration. Possible side effects include lymphopenia, bradycardia, and hepatotoxicity.

Patients with secondary progressive MS, progressive-relapsing MS, and primary progressive MS appear to represent primarily neurodegenerative processes. Disease-modifying therapies are, therefore, less effective, and treatment with these therapies has ranged from possible benefit to little effect on disease progression. Young patients with a short duration of progression seem to derive the most benefit.

The following principles highlight the treatment of acute relapses:

- Treatment of a possible underlying process which could have triggered a relapse (such as an infection or metabolic derangement)

- Symptomatic treatment based on specific neurologic symptoms

- A short course of corticosteroids to assist in recovery

- Rehabilitation with involvement of physical and occupational therapy

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of MS is extensive and broad and can categorize into seven categories:

- Other demyelinating or inflammatory CNS syndromes: Examples include optic neuritis, Marburg disease, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Devic neuromyelitis optica, and partial transverse myelitis.

- General inflammatory and autoimmune syndromes. Examples include systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, and Sjogren syndrome.

- Infectious etiologies such as Lyme disease, syphilis, HIV, and herpes viruses

- Vascular etiologies such as migraine headaches, small vessel ischemia, vascular malformations and emboli

- Metabolic causes that include vitamin deficiencies and thyroid disease

- Uncommon genetic etiologies that include mitochondrial cytopathy, Fabry disease, Alexander disease, hereditary spastic paraplegia

- Neoplastic causes that include primary CNS malignancies or metastasis

Prognosis

The prognosis and severity of the disease vary between patients.[25] The condition is often mild early on in the disease and worsens as time progresses.

Factors that suggest a worse prognosis include:

- Male gender

- Progressive course

- Primarily pyramidal or cerebellar symptoms

- More frequent relapses

- Minimal recovery between relapses

- Multifocal onset

- High early relapse rate

- Large lesion load and brain atrophy on MRI

Factors that suggest a favorable diagnosis include:

- Female gender

- Relapsing course

- Mild relapses

- Good recovery between exacerbations

- Primarily sensory symptoms

- Long interval between first and second relapses

- Low lesion load on MRI

- Presentation of optic neuritis

- Full recovery from exacerbations

Complications

The long term disability of MS reflects an accumulation of symptoms from each successive incomplete recovery from relapse.

- Impaired mobility occurs in a majority of patients with long term MS. Reduction in mobility is multifactorial and possibly relates to defective motor control and vestibular symptoms.

- Brain stem lesions involving the oculomotor pathways can cause chronic diplopia. This condition is potentially addressable by prisms and surgery.

- Chronic vertigo is a possible source of morbidity and may respond to meclizine, ondansetron, or diazepam.

- Chronic dysphagia from bulbar dysfunction can be a source of chronic aspiration.

- Cerebellar tremor is a possibly significant source of disability. Wrist weights have a possible role in the management of tremors; however, potential superimposed weakness can preclude the use of wrist weights.

- Urinary tract infections from bladder dysfunction is a known longer-term complication and often requires urology consultation.

- Constipation is the most frequent gastrointestinal complication, and management includes patient education and treatment with increased fiber intake and bulk-forming agents.

- Erectile dysfunction, when present, is often treated with oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

- Cognitive impairment, mood disorders, and generalized fatigue are known long term sources of morbidity and are managed in various ways, often with the help of subspecialty care.

Consultations

MS is a complex neurologic disorder that results in both neurologic and non-neurologic symptoms, disability, and complaints. A multidisciplinary team approach includes the involvement of the following specialties:

- Neurology and neuro-ophthalmology

- Psychiatry/ cognitive psychology

- Pain management

- Nursing/physician assistants

- Speech therapy

- Occupational therapy

- Social work

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation

- Urology (in the setting of genitourinary complications)

- Gastroenterology (in the setting of gastrointestinal complications)

Deterrence and Patient Education

A diagnosis of MS can be difficult for a patient, and the physician plays a supportive role in counseling the patient about the diagnosis. Predicting disease course is difficult, and a provider should educate the patient on the wide range of possibilities in disease progression.

Clinicians should emphasize that patients often do well and explain the role of effective medications on disease treatment. Patients should receive counsel on reliable sources online on learning about their diagnosis. Reliable sources include the MS International Federation and the National MS Society. Educating the patient on the nature of relapses and long term complications is essential. Patients should know to contact their provider if they experience new neurologic symptoms that last greater than 24 hours, as this may require the administration of corticosteroids. Emphasizing smoking cessation, Vitamin D supplementation, a balanced diet, and other lifestyle medications is also important. A patient should also be counseled on the importance of compliance with disease-modifying therapy, considering the side-effect profile of these medications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Multiple sclerosis is a complex disease process. In addition to sensory and visual changes, weakness, coordination problems, or spasticity can present. Other complaints relating to overall health include bladder and bowel dysfunction, depression, cognitive impairment, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and vertigo. Because of reduced life expectancy and multisystem involvement, the disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a neurologist, pain specialist, physical and/or occupational therapist, nurse specialist, ophthalmologist, mental health nurse, gastroenterologist, and a urologist. [Level 5]