Continuing Education Activity

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that results in chronic inflammation and damage of more than one organ. It is diagnosed clinically and serologically with the presence of autoantibodies. "Lupus" is a Latin term meaning "wolf," since one of the hallmark facial SLE rashes is similar to the bitemark of a wolf. Lupus nephritis typically occurs after at least three years since the onset of SLE. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis of lupus nephritis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Explain the pathophysiology of lupus nephritis.

- Review the presentation of a patient with lupus nephritis.

- Outline the management options available for lupus nephritis.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with lupus nephritis.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that results in chronic inflammation and damage of more than one organ. It is diagnosed clinically and serologically with the presence of autoantibodies. "Lupus" is a Latin term meaning "wolf," since one of the hallmark facial SLE rashes is similar to the bitemark of a wolf. In 400 BC, the "father of medicine," Hippocrates, was the first to document a case of lupus. From 1700 to 1800s, it was debated whether lupus was associated with tuberculosis or syphilis. Lupus evolved from being viewed as solely a dermatologic manifestation into an all-inclusive multisystemic disease.

One common and dire manifestation that should be looked for in SLE is the involvement of the kidneys, known as lupus nephritis (LN). Evaluating kidney function in patients suffering from SLE is important as timely detection and management of renal impairment can greatly improve renal outcomes. Lupus nephritis typically occurs three years after and usually within 5 years of the onset of SLE. Histological evidence of lupus nephritis is present in most patients with SLE, even in those who do not clinically manifest renal disease. Monitoring for the development of lupus nephritis is done with serial creatinine, urine albumin-to-creatine ratio, and urinalysis. This helps in gauging a rise in serum creatinine value from the baseline as well as for the presence of proteinuria that is commonly observed with lupus nephritis. Since lupus nephritis carries a high risk for increased morbidity, treatment plays an important role in preventing progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).[1][2][3][4]

The primary goal of treatment in lupus nephritis is the normalization of the kidney function or, at least, the prevention of progressive decline of kidney function. There is variability in the treatment options depending on the underlying pathologic lesion.[5][6]

Etiology

Lupus nephritis is a common manifestation of SLE. It is primarily caused by a type-3, hypersensitivity reaction, which results in the formation of immune complexes. Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) binds to DNA, which forms an anti-dsDNA immune complex. These immune complexes deposit on the mesangium, subendothelial, and/or subepithelial space near the glomerular basement membrane of the kidney. This leads to an inflammatory response with the onset of lupus nephritis, in which the complement pathway is activated with a resultant influx of neutrophils and other inflammatory cells. While an autoimmune phenomenon causes lupus nephritis, there are also genetic components that may predispose an SLE patient to develop lupus nephritis. For instance, polymorphisms in the allele coding for the immunoglobulin receptors on macrophages and APOL1 gene variations found exclusively in African American populations with SLE were found to be associated with predisposition to lupus nephritis.[7][8][9]

Genetic Factors

As with many other autoimmune diseases, genetic predilection plays a significant role in the occurrence of both SLE and lupus nephritis. It is considered to be a polygenic phenomenon that is yet to be completely understood. Following are some important genetic associations found in patients suffering from SLE or lupus nephritis:

- PTPN22 - Lymphoid-specific protein tyrosine phosphatase

- CRP

- FCGR3A, FCGR3B - FcγRIIIA (V176), FcγRIIIB

- FCGR2A, FCGR2B - FcγRIIA (R131), FcγRIIB

- C1QB - C1q deficiency

- STAT4 - Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4

- CTLA4 - Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4)

- C2, C4A, C4B - C2, C4 deficiencies

- HLA-DRB1 - HLA-DRB1: DR2/1501, DR3/0301C1q deficiency

- TNF - TNF-a (promoter, -308)

- MBL2 - Mannose-binding lectin

SLE is more commonly observed in first-degree relatives of patients suffering from SLE (familial prevalence is 10-12%). Monozygotic twins are found to have higher concordance rates (24-58%) than dizygotic twins (2-5%). This supports the idea of significant genetic involvement in the development of SLE. However, the fact that the concordance rate is not 100% in monozygotic twins suggests that environmental factors also play an important role in the development of clinical disease. Some important genes that play a role in lupus nephritis are:

-

C1Q, C1R, and C1S deficiencies are linked with SLE, lupus nephritis, and the appearance of anti-dsDNA

-

C2 and C4 deficiencies are related to the development of SLE or a lupus-like syndrome

-

FcγRIIa is associated with lupus nephritis in African Americans

Immunologic Factors

The initial response appears to be autoantibody-mediated against the nucleosome, from apoptotic cells.[10][11] Patients suffering from SLE have impaired clearance mechanisms for cellular debris. Nuclear debris in apoptotic cells causes plasmacytoid dendritic cells to release interferon-α, which acts as a strong inducer of the immune system and autoimmune response.[12]

Autoreactive B lymphocytes become activated in SLE because of a disordered response of normal homeostatic mechanisms, causing an escape from tolerance. This in turn results in the production of autoantibodies.

Other autoantibodies, such as anti-dsDNA antibodies appear through a process called epitope spreading. These autoantibodies appear gradually, in an orderly fashion, from months to years prior to the development of clinical SLE.

Epidemiology

In a multiethnic international study, it was found that patients who were suffering from lupus nephritis were more frequently men, relatively younger, and of African, Asian, and Hispanic ethnicity.[13]

In a large Spanish study, lupus nephritis was confirmed histologically in 30.5% of patients with SLE. The mean age of diagnosis for lupus nephritis was observed to be 28.4 years. The risk for the development of lupus nephritis was significantly higher in younger individuals, men, and Hispanics. Interestingly, patients receiving antimalarial drugs had a significantly reduced risk of developing lupus nephritis.[14]

Age-related

Most patients with SLE end up developing lupus nephritis earlier in the disease course. SLE is more commonly seen in women in the third decade, and lupus nephritis essentially occurs in patients 20 to 40 years old. Children with SLE appear to be at a higher risk of having renal involvement than adults.[15][16]

Sex-related

Generally, the prevalence of SLE is higher in women (female-to-male ratio of 9:1). Likewise, lupus nephritis is also more common in women; however, clinically evident renal disease with a worse prognosis is more common in men with SLE.

Race-related

SLE is more prevalent in African Americans and Asians than in Whites, with the highest prevalence seen in Caribbean people. Although lupus nephritis is more common in Asians than in Whites, the 10-year outcome and survival rate are observed to be better in Asians.[17]

Pathophysiology

Lupus nephritis is a type-3 hypersensitivity reaction. This occurs when immune complexes are formed. Autoimmunity plays a significant role in the development of lupus nephritis leading to the production of autoantibodies that are directed against nuclear elements. The characteristics of these autoantibodies in relevance to lupus nephritis are:[18]

-

Anti-dsDNA antibodies may cross-react with the glomerular basement membrane

-

Higher-affinity autoantibodies may result in intravascular immune complexes that get deposited in glomeruli

-

Cationic autoantibodies have a greater affinity for the anionic basement membrane

-

Activation of complements by autoantibodies of certain isotypes

These autoantibodies make immune complexes within the vessels that are deposited in glomeruli. Alternatively, autoantibodies may form immune complexes in situ by binding to antigens that are already located in the glomerular basement membrane. Immune complexes induce an inflammatory response by the activation of the complement system and recruitment of inflammatory cells. Glomerular thrombosis is another phenomenon that plays a part in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis particularly in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome and is believed to be the result of an interaction between antibodies and negatively charged phospholipid-proteins.

Azzouz and colleagues analyzed that specific strains of a gut commensal may add to the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. When patients with SLE were stratified according to organ involvement, ones with a history of renal impairment showed a great number of RG-specific amplicon sequence variants as opposed to those who had no renal disease.[19]

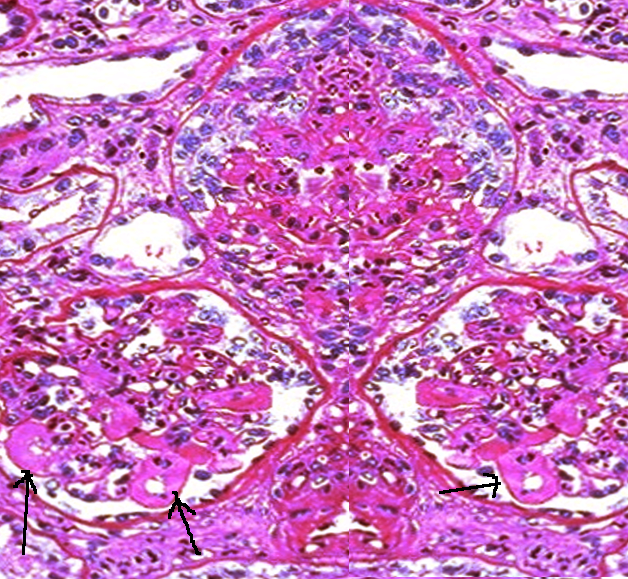

Histopathology

The histologic type of lupus nephritis that develops depends on numerous factors, including the antigen specificity and other properties of the autoantibodies and the type of inflammatory response that is determined by other host factors. In more severe forms of lupus nephritis, the proliferation of endothelial, mesangial, and epithelial cells and the production of matrix proteins lead to fibrosis.

Lupus nephritis may affect different compartments of the kidney, which are the glomeruli, interstitium, tubules, and capillary loops. Aside from anti-dsDNA immune complex deposits, immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and complement (C1, C3, and properdin) are commonly found as mesangial, subendothelial, and subepithelial deposits. Leukocytes may also be present.

The current standardized classification system for lupus nephritis is derived from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society's recommendations. The classification system is based on glomerular morphologic changes seen on microscopy, immune deposits seen on immunofluorescence, and also electronic microscopy.

- Class 1 is minimal mesangial lupus nephritis, in which glomeruli appear normal on light microscopy. Immunofluorescence shows immune complex deposits in the mesangial space.

- Class 2 is proliferative mesangial lupus nephritis since mesangial proliferation is seen on light microscopy unlike class 1. Similar to class 1, immunofluorescence also shows immune complex deposits in the mesangial space.

- Class 3 is focal lupus nephritis. Immune complex deposits may be visualized in the mesangial, subendothelial, and/or subepithelial space on immunofluorescence imaging.

- Class 4 is the diffuse type in which immune complex deposits may occur in the mesangial, subendothelial, and/or subepithelial space. Lesions may be segmental, involving less than 50% of the glomeruli, or global, which instead involves more than 50%.

- Class 5 is membranous LN, in which immune complex deposits are in the mesangial and subepithelial space. Capillary loops are thickened due to subepithelial immune complex deposits. In this class, nephrotic range proteinuria occurs. Class 5 may also include class 3 and 4 pathology.

- Class 6 is advanced sclerosing lupus nephritis in which most of the glomeruli are sclerosed. However, immune complex deposits are not visualized on immunofluorescence since more than 90% of the glomeruli are scarred.

History and Physical

Patients with lupus nephritis already have varying clinical manifestations of SLE. These clinical symptoms include malar or discoid rash, fatigue, fever, rash, photosensitivity, serositis, oral ulcers, non-erosive arthritis, seizures, psychosis, or hematologic disorders. Lupus nephritis is diagnosed through laboratory findings, such as proteinuria or cellular casts. Typically, patients with lupus nephritis are asymptomatic. Some patients with lupus nephritis may develop polyuria, nocturia, foamy urine, hypertension, and edema. Early signs of proteinuria, which indicate tubular or glomerular dysfunction, are the presence of foamy urine or nocturia. If the degree of proteinuria meets the nephrotic syndrome criteria of more than 3.5 grams per day of protein excretion, then peripheral edema develops due to hypoalbuminemia. There may also be microscopic hematuria that is not grossly visible.

Some patients have an asymptomatic disease; however, in regular follow-up, laboratory abnormalities such as raised serum creatinine levels, hypoalbuminemia, or proteinuria or sediment indicate active lupus nephritis. This is frequently observed in mesangial or membranous lupus nephritis.

Symptoms seen in active lupus nephritis may include peripheral edema because of hypertension or hypoalbuminemia. Significant peripheral edema is more commonly seen in patients with diffuse or membranous lupus nephritis because these renal lesions have a remarkable association with heavy proteinuria.

Other symptoms that are directly linked to hypertension are commonly seen in diffuse lupus nephritis and they include dizziness, headache, visual disturbance, and signs of cardiac compromise.

The physical examination in focal and diffuse lupus nephritis may reveal evidence of generalized SLE with the presence of oral or nasal ulcers, a rash, synovitis, or serositis. Signs of active nephritis are common as well.

Signs of an isolated nephrotic syndrome are commonly seen in membranous lupus nephritis, such as peripheral edema, ascites, and pericardial pleural and effusions without hypertension.

Evaluation

Laboratory

With active SLE, complement levels (C3 and C4) are usually low with the presence of anti-dsDNA autoantibody. Creatinine (Cr) may be elevated or normal with the presence of proteinuria. Urinalysis shows the presence of proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, red blood cells, or red blood cell casts. The presence of protein in urine indicates glomerular damage. Proteinuria that exceeds more than 3.5 g per day is in the nephrotic range. If significant proteinuria exists, a complete metabolic panel (CMP) will show a low albumin count.

Screening for proteinuria and hematuria is recommended every three months in active SLE.

Radiographic

Bilateral kidney ultrasound should be obtained to rule out hydronephrosis or obstructive cause.

Biopsy

A kidney biopsy is indicated when the patient develops nephrotic range proteinuria. It may also be useful in patients with repeated episodes of nephritis. With the help of renal biopsy, the histologic form and stage of disease (activity and chronicity) can be established which is, in turn, helpful in determining prognosis and treatment. A detailed clinical and laboratory evaluation can be used to predict the histologic pattern of lupus nephritis in around 70-80% of patients; however, it is not accurate enough.

A good rule is to carry out a kidney biopsy if the outcome will potentially change patient management. If a patient has other manifestations of SLE (such as severe central nervous system or hematologic involvement) and is going to be treated with cyclophosphamide, a biopsy may not be essential but should be considered as it may help predict the renal outcome. Sampling errors can occur during a renal biopsy. Therefore, the biopsy results should always be evaluated in relevance to the clinical presentation and laboratory results of the patient. The expertise of pathologists in interpreting lupus nephritis biopsy specimens differs a great deal. Studies have revealed that the most consistent reporters are in larger medical centers where a substantial number of patients with SLE are found.

Class 1 - Minimal Mesangial Lupus Nephritis

- Light microscopy findings - Normal

- Immunofluorescence electron microscopy findings - Mesangial immune deposit

Class 2 - Mesangial Proliferative Lupus Nephritis

- Light microscopy findings - Mesangial hypercellularity purely or expansion of mesangial matrix with mesangial immune deposits

- Immunofluorescence electron microscopy findings - Mesangial immune deposits with few immune deposits in subepithelial or subendothelial spaces possible

Class 3 - Focal Lupus Nephritis

- Light microscopy findings - Active or inactive with focal, segmental, or global involvement affecting fewer than 50% of all glomeruli

- Immunofluorescence electron microscopy findings - Mesangial and subendothelial immune deposits

Class 4 - Diffuse Lupus Nephritis

- Light microscopy findings - Active or inactive with diffuse, segmental, or global involvement affecting approximately 50% of all glomeruli. It is subdivided into diffuse segmental (class 4-S) when around 50% of involved glomeruli manifest segmental lesions (meaning less than half of glomerular tuft is affected) and diffuse global (class 4-G) when approximately 50% of affected glomeruli have global lesions. It shows wire-looping.

- Immunofluorescence electron microscopy findings - Subendothelial immune deposits

Class 5 - Membranous Lupus Nephritis

- Light microscopy findings - Diffusely thickened glomerular basement membrane with no inflammatory infiltrate. It can possibly show subepithelial deposits and basement membrane spikes on specific stains, such as silver and trichrome. It may occur in combination with class 2 or 4 and may reveal advanced sclerosis.

- Immunofluorescence electron microscopy findings - Subepithelial and intramembranous immune deposits.

Class 6 - Advanced Sclerosis Lupus Nephritis

- Light microscopy findings - Advanced glomerular sclerosis affecting almost 90% of glomeruli, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis, all manifestations of irreversible renal injury

Treatment / Management

Treatment is largely based on the class types of lupus nephritis as discussed in the histopathology section. Class 1 and 2 may generally be monitored and do not need treatment. Immunosuppressive and steroid treatment is needed with classes 3 and 4. Renal replacement therapy is considered in class 6 where most of the glomeruli have sclerosed. Active disease in lupus nephritis typically predicts a better response to treatment, unlike chronic disease.

Treating risk factors that may cause progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is also important. Starting a statin medication to lower lipids is necessary since CKD increases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Antihypertensive therapy with either angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin 2 receptors blockers (ARBs) in patients with proteinuria and/or hypertension is indicated.

Treatment of lupus nephritis includes the induction phase and the maintenance phase using immunosuppressive and nonimmunosuppressive therapies. The induction phase is primarily used to elicit a renal response through the use of immunosuppressive agents and anti-inflammatory medications. After obtaining a renal response, maintenance therapy is used for a prolonged period with immunosuppressives and nonimmunosuppressive agents. This prevents relapse but requires regular monitoring while on the therapy. During induction therapy, prophylaxis against pneumocystis pneumonia should be given. A concern with chronic glucocorticoid use is a loss of bone density. Taking appropriate measures to prevent bone density loss with appropriate supplementation and a baseline DEXA scan is important.[20][21]

Class 3 and 4 Induction Therapy

It is started with mycophenolate mofetil for 6 months with 3 days of intravenous glucocorticoid followed by prednisone tapered to the lowest dose. After 6 months, if there is an improvement, continue on a lower dose of mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. If there is no improvement or sufficient renal response after 6 months, switch to cyclophosphamide with pulse glucocorticoid followed by daily glucocorticoid. If there is a good renal response to this, the patient may be maintained on a low dose of mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. If there is no response to the cyclophosphamide-glucocorticoid treatment, the patient may be trialed on rituximab or calcineurin inhibitors with the addition of glucocorticoid. This induction therapy is used more for the Hispanic and African American races.

An alternative to mycophenolate mofetil is starting induction therapy with cyclophosphamide and pulse dosing of glucocorticoid for 3 days followed by oral prednisone taper. If the patient has European ancestry, then therapy would be transitioned into low-dose cyclophosphamide followed by oral mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. If the patient does not have European ancestry or white race, then treatment after prednisone taper would be transitioned to high dose cyclophosphamide for six months. After 6 months of therapy with either low or high-dose cyclophosphamide, the renal response is assessed. If there is a good renal response, then the patient may transition to maintenance therapy with mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. If there is poor or no renal response, the patient would continue high-dose mycophenolate mofetil with pulse glucocorticoid followed by oral prednisone for another 6 months. Afterward, if there is no improvement, the patient should be trialed on rituximab or calcineurin inhibitor with glucocorticoid therapy. If there is a good renal response, the patient may be transitioned to maintenance therapy of low-dose mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

Class 5 Induction Therapy

Mycophenolate mofetil high dose with prednisone is started for 6 months. If there is a good clinical response, then maintenance therapy is resumed with either mycophenolate mofetil at a lower dose or azathioprine. If no improvement, then cyclophosphamide with pulse dose glucocorticoids is continued for an additional 6 months.

Treatment of classes 3, 4, and 5 in pregnancy differs from the typical treatment previously discussed. Glucocorticoids are used in active lupus nephritis, either prednisone, dexamethasone, or betamethasone. Azathioprine may be included if doses of glucocorticoid may be reduced. If a pregnant female patient has mild lupus nephritis, hydroxychloroquine is used as the primary treatment. If instead, the pregnant female has clinically active lupus nephritis, then prednisone specifically is started.

All patients with lupus nephritis must be started on hydroxychloroquine on background unless there is a contraindication. A recent trial revealed that individuals on hydroxychloroquine have fewer flare-ups compared to those not treated. In addition, the patient should receive glucocorticoids combined with mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes other causes of nephrotic syndrome, nephrolithiasis, hydronephrosis, acute kidney injury due to medication, and acute interstitial nephritis. Besides the list of differential diagnoses, other disorders to be considered include:

Differential Diagnoses

- Chronic glomerulonephritis

- Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

Prognosis

Although lupus nephritis does have associated morbidity and mortality, the prognosis of LN relies on which WHO histopathology class it specifically meets. Class 1 (minimal) and class 2 (proliferative mesangial) share a good long-term prognosis. As lupus nephritis progresses and advances different classes, the prognosis worsens. Class 3 has a poor prognosis. Class 4 has the poorest prognosis. Prognosis also depends on how early therapy is initiated. The earlier the therapy is started in the disease course the better the disease outcome is.

Over the past four decades, alterations in the treatment of lupus nephritis have significantly improved both renal impairment and overall survival. During the 1950s, the 5-year survival rate among patients with lupus nephritis was close to 0%. The subsequent addition of immunosuppressive agents such as intravenous (IV) pulse cyclophosphamide has led to documented 5- and 10-year survival rates as high as 85% and 73%, respectively.

Mortality associated with lupus nephritis in patients with end-stage renal disease has declined significantly in the past few decades. The mortality rate per 100 patient-years reduced from 11.1 in 1995-1999 to 6.7 in 2010-2014. Cardiovascular disease-related deaths declined by 44% and deaths due to infection declined by 63%.[22]

Nephrotic syndrome may result in edema, ascites, and hyperlipidemia, increasing the risk of coronary artery disease and thrombosis. The reports from one study show that patients with lupus nephritis, specifically early-onset lupus nephritis, are at greater risk of developing morbidity from ischemic heart disease.[23]

Complications

Following are some important complications that the providers should be mindful of:

- Hypertension (sometimes refractory)

- Excessive edema

- Chronic kidney disease

- End-stage renal disease (ESRD)

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be made aware of the signs and symptoms of lupus nephritis and when to seek professional help. If it comes to renal replacement therapy, patients and their families should be given information and support in terms of hemodialysis and renal transplant. Patients who are suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus should be informed that early detection of its complications, such as lupus nephritis can lead to prompt treatment and better long-term outcomes. Pharmacists should make patients aware of the commonly used drugs and side effects associated with them. The role of the nurses comes in for holistic education of the patients and their families.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of lupus nephritis is interprofessional that includes a nephrologist, hematologist, rheumatologist, internist, cardiologist, and intensivist. The aim of treatment is to prevent the progression of renal disease. These patients need very close monitoring because not only does lupus have high morbidity, but the drugs used to manage the symptoms also have a number of serious adverse effects. The overall prognosis for patients with lupus nephritis is guarded. When the disease advances, end-stage renal failure is inevitable.[7][24] [Level 2] Patients should be educated about renal transplant and its benefits before the disease has progressed.