Continuing Education Activity

Acute respiratory failure is caused by a wide range of etiologies. Progression to cardiopulmonary arrest and ultimately death is likely in the absence of effective and timely airway management. Therefore, one of the primary goals of airway management is to provide adequate ventilation and oxygenation to avoid or halt the progression to cardiopulmonary arrest. Effective and timely airway management is also an essential component of successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. This activity describes the indications and techniques for securing a patent oropharyngeal airway and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with oropharyngeal airways.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for an oropharyngeal airway.

- Describe the technique for placing an oropharyngeal airway.

- Explain the clinical utility of an oropharyngeal airway.

- Employ interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to ensure appropriate maintenance of an oropharyngeal airway and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Acute respiratory failure is caused by a wide range of etiologies. Progression to cardiopulmonary arrest and ultimately death is likely in the absence of effective and timely airway management. Therefore, one of the primary goals of airway management is to provide adequate ventilation and oxygenation to avoid or halt the progression to cardiopulmonary arrest. Effective and timely airway management is also an essential component of successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Airway management is critical in the pediatric population as pediatric airway problems are commonly seen in pediatric and general emergency departments. Respiratory distress is the fourth most common chief complaint in children presenting to the emergency department.[1][2][3]

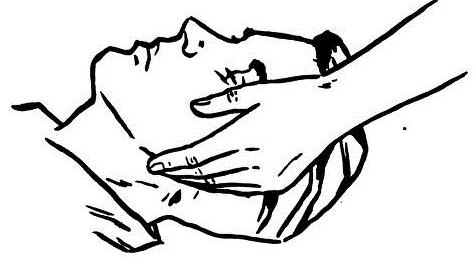

Initial steps in airway management include airway positioning maneuvers (for example, head-tilt-chin lift, jaw-thrust), suctioning, supplemental oxygen, and re-positioning of the airway if the previous steps are ineffective. Airway positioning maneuvers place the airway in a neutral position and help move the tongue and palatal tissues away from the posterior wall of the pharynx. When choosing an airway positioning maneuver, one must be cognizant of the possible presence or absence of a cervical spine injury. Suctioning assists with the removal of secretions that could be causing or contributing to airway obstruction. If these steps do not help in maintaining a patent airway or in providing adequate ventilation and oxygenation, then an airway adjunct should be utilized.

Airway adjuncts are used to relieve or bypass an upper airway obstruction during airway management. However, upper airway obstruction may be present for several reasons, and airway adjuncts may not be able to relieve or bypass all types of obstruction. Upper airway obstruction may occur from anatomical causes such as choanal atresia, pathological causes such as a tonsillar abscess or adverse effects from patient management such as loss of airway patency during the administration of sedation and/or analgesia.[4][5]

There are also subsets of patients that are more prone to develop upper airway obstruction. Patients with obesity are at significant risk for upper airway obstruction due to altered upper airway anatomy. Pharyngeal tissues have increased fat deposition causing excess upper airway tissue and an increased likelihood of pharyngeal wall collapse resulting in airway obstruction. This can be exacerbated when patients with obesity are given drugs that depress the central nervous system or have other co-morbidities, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and/or obstructive hypoventilation syndrome (OHS). The presence of OSA and/or OHS can be associated with increased sensitivity to the respiratory depressant effects of sedatives and opioids increasing the tendency to obstruct the airway.

Pediatric patients, in particular infants and young children, are susceptible to upper airway obstruction. This predisposition is due to the differences between pediatric and adult airways. Infants and young children have a relatively large occiput that causes neck flexion when lying supine. This results in a natural tendency to obstruct the upper airway. They have a proportionally large tongue relative to the size of their oral cavity which also causes a natural obstruction of the airway. Additionally, a shortened thyromental distance in this patient population brings the tongue into proximity of the soft palate. Consequently, this leads to obstruction of the airway. Lastly, compared to adults, infants and young children have larger adenoidal tissue, as well as, more distensible and compliant larger airways which predisposes them to airway obstruction. In general, by the age of eight, the pediatric airway is very similar to that of an adult airway.

There are two types of airway adjuncts. One is an oropharyngeal airway, and the other is a nasopharyngeal airway. This article will summarize the former.

Indications

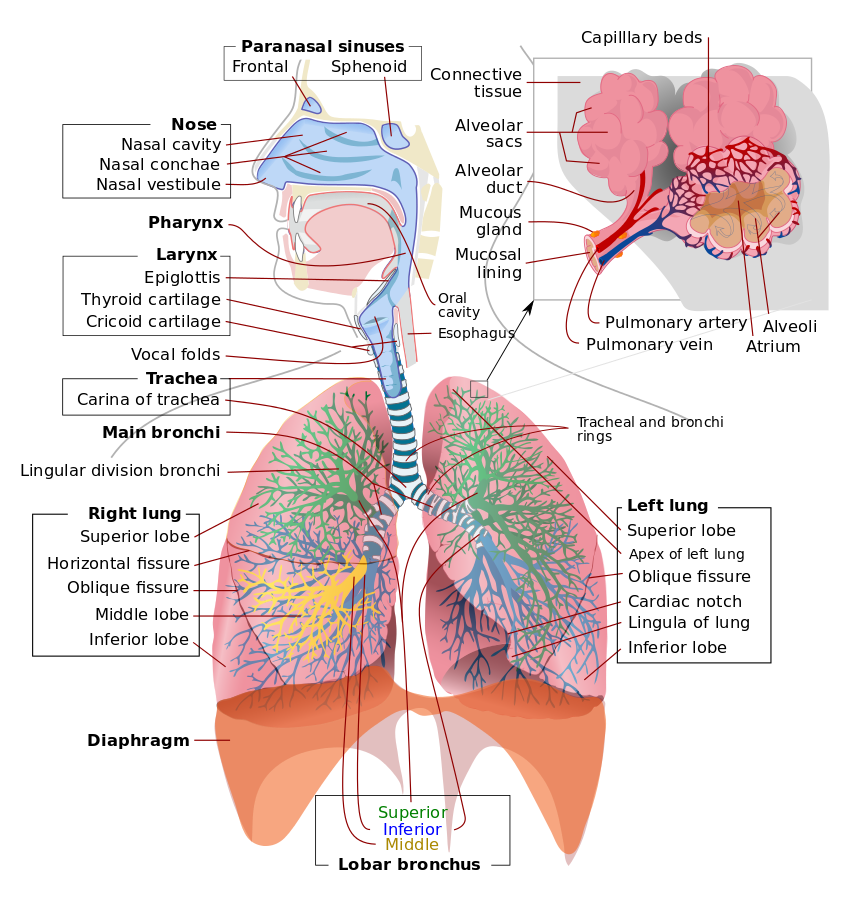

An oropharyngeal airway (oral airway, OPA) is an airway adjunct used to maintain or open the airway by stopping the tongue from covering the epiglottis. In this position, the tongue may prevent an individual from breathing. This sometimes happens when a person becomes unconscious because the muscles in the jaw relax causing the tongue to obstruct the airway.

Contraindications

Avoid using an oropharyngeal airway on a conscious patient with an intact gag reflex. If the patient can cough, they still have a gag reflex, and an oral airway is contraindicated. If the patient has a foreign body obstructing the airway, an oropharyngeal airway should not be used. An oropharyngeal airway should not be used on patients who have nasal fractures or an actively bleeding nose.

Preparation

An oropharyngeal airway has four parts: the flange, the body, the tip, and a channel to allow for passage of air and suction. Oropharyngeal airways come in a wide range of sizes (e.g., 40 mm to 110 mm). Choosing an appropriate oropharyngeal size is determined on an individual basis through the use of anatomical landmarks. When determining the appropriate oropharyngeal size for a patient, one must assess where the oropharyngeal airway parts lie in relation to the patient’s anatomical landmarks. The flange should be approximated, externally, to where it is abutting the lips, and the tip should be able to reach the angle of the mandible. Insertion of an oropharyngeal airway is not complicated but must be done with care to avoid further worsening of the airway obstruction, as well as, injuries to the airway.

Technique or Treatment

There are several techniques, and the following are a few examples:

Technique 1: First, open the mouth. Then, using a tongue depressor, push down on the tongue and, with the tip pointed caudally, insert the oropharyngeal airway directly into the mouth over the tongue.

Technique 2: First, open the mouth. Then, with the tip pointed cephalad, insert the oropharyngeal airway into the mouth and then rotate it 180 degrees as it is advanced to the back of oropharynx. This technique carries the potential of injuring the hard and soft palates of the oral cavity.

Technique 3: First, open the mouth. Then, with the tip pointed at a corner of the mouth, insert the oropharyngeal airway into the mouth and then rotate it 90 degrees as it is advanced to the back of oropharynx.

Complications

Complications potentially caused by the use of oropharyngeal airways are that it may induce vomiting which may lead to aspiration. Additionally, it may cause or worsen airway obstruction if an inappropriately sized airway is used (i.e., too small). An inappropriately sized airway can also cause laryngospasm (i.e., too big). Lastly, damage to the oral structures or dentition can also result from oropharyngeal airway insertion.

Clinical Significance

A clear, patent airway is a fundamental requirement for effective resuscitation. Therefore, the presence of an upper airway obstruction can pose a barrier towards effective resuscitation by preventing adequate oxygenation and ventilation. An oropharyngeal airway can potentially bypass an airway obstruction any of the oral structures may cause, for example, a tonsillar hypertrophy. It can also serve to relieve obstruction caused by the tongue, particularly in a supine patient whose tongue tends to fall back onto the posterior pharynx. By the same mechanism, an oropharyngeal airway could also make bag-mask ventilation more effective further aiding in the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[6][7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The presence of a patent airway is vital for survival. All healthcare workers should know the importance of an airway and the type of disorders that can compromise oxygenation. If there is any doubt about the airway, an anesthesiologist should be consulted. In severe cases, even a delay of a few minutes can prove to be fatal.