Continuing Education Activity

Osteochondromas are common benign osseous surface lesions generally arising from the metaphysis of long bones. The lesions are most commonly asymptomatic and found incidentally. However, there are several well-documented complications, including but not limited to fracture, bursa formation, neurovascular compression, and malignant degeneration. This activity reviews the pathophysiology and etiology of osteochondromas highlighting the role of the interprofessional team in evaluation and management.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of osteochondromas.

- Describe the differences in solitary (non-hereditary) and multiple (HME) forms.

- Outline the clinical presentation of osteochondromas.

- Explain the role of the interprofessional team in the diagnosis and management of osteochondrosis to help improve outcomes.

Introduction

Osteochondromas represent the most common bone tumor accounting for 20 to 50% of all benign osseous tumors.[1][2] Osteochondromas are surface bone lesions composed of both cortical and medullary bone with hyaline cartilage caps. The presence of cortical and medullary continuity of the tumor with the underlying bone is a pathognomonic feature that establishes the diagnosis.[1][2][3] Osteochondromas may be solitary or multiple. The multiple form is an autosomal dominant syndrome referred to as hereditary multiple exostosis (HME) or familial osteochondromatosis.

Complications associated with osteochondromas are common, including osseous deformities, fracture, bursa formation with or without bursitis, vascular compromise, neurologic symptoms, and malignant transformation.[1][2][3][4] Radiographs are often diagnostic, however cross-sectional imaging may be indicated to assess for complications, assess the cartilage cap or in some challenging cases establish the presence of medullary continuity. The lesions may increase in size in skeletally immature patients, however growth or changes in morphology after skeletal maturation are concerning features for malignant transformation. The lesions may be sessile or pedunculated. When pedunculated they extend away from the nearest joint.[1] There are multiple osteochondroma variants and/or mimickers including subungual exostosis, dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica (Trevor disease), turret exostosis, traction exostosis, bizarre parosteal osteochondroma Tous proliferation (BPOP or Nora lesion), and florid reactive periostitis.[1][5] Differential considerations would also include subperiosteal hematoma, parosteal osteosarcoma or juxtacortical chondroma, none of which would have medullary continuity.[2][3][5][6][7]

Etiology

Osteochondroma can present in the form of a solitary lesion or as a part of numerous osteochondromas in patients with multiple hereditary exostoses (HME).[1] Some studies in the literature suggest osteochondromas are developmental lesions as oppose to true neoplasms resulting from the separation of cells from the epiphyseal growth plate. This hypothesis has support from reported cases of osteochondroma developing following trauma or irradiation.[1] However, more recent studies suggest that osteochondromas may truly be neoplasms as genetic mutations have appeared in both MHE and solitary forms.[8] The categorization of solitary osteochondromas is according to the etiology into a primary and secondary osteochondroma. Primary osteochondroma develops spontaneously with no precipitating event while secondary osteochondroma can develop either due to childhood radiational exposure or due to trauma (surgery or Salter-Harris-fractures). Post-irradiation prevalence ranges from 6 to 24%, thereby representing the most common benign radiation-induced tumor. The latency period for post-radiation osteochondromas ranges from 3 to 17 years.[1][9][10]

Epidemiology

Osteochondroma is the most common benign bony tumor, accounting for 30% (range 20-50%) of all benign bony tumors and 10% to 15% of both benign and malignant bony tumors combined. Solitary osteochondromas are so common that 1 to 2% of patients undergoing radiographic evaluation will have an incidental lesion. The solitary form constitutes the majority of cases (85%) and is usually asymptomatic.[1][2] The lesions are typically discovered in childhood, 75 to 80% before 20 years of age, with symptomatic lesions generally presenting in younger patients.[1] Patients with HME are more likely to be symptomatic and are more severely affected, therefore presenting at a younger age.[1] There is a male predilection for both the solitary and hereditary forms. The hereditary form is autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance in females with an incidence of 1 per 50000 to 100000 in Western populations.[1]

Since the lesions develop from cartilage cells displaced from the growth plates, any bone that develops via enchondral ossification may develop an osteochondroma. The long bones constitute the majority of cases (50%), with a 2 to 1 lower extremity to upper extremity ratio. The femur is the most commonly affected long bone (30% of cases) with distal lesions more common than proximal. The tibia and humerus are the next most common long bones, each constituting 10 to 20% of cases. Proximal tibia involvement is more common than distal; therefore, osteochondromas about the knee are extremely common. When flat bones (pelvis, scapula, and spine) are involved, medullary continuity is less evident on the radiographs, and cross-sectional imaging is often required to characterize definitively.[1][2][9][10]

Pathophysiology

Solitary osteochondroma

Literature suggests that solitary osteochondromas may result from a developmental abnormal rather than representing a true neoplasm.[1] The proposed hypothesis is that a fragment of the growth plate herniates through the periosteum, which then continues to grow, resulting in either a sessile or pedunculated lesion most commonly in the region of the metaphysis.[1][2] The separation of the growth plate fragment can occur either spontaneously (primary osteochondroma), or secondary resulting from irradiation, surgery, or fractures (secondary osteosarcoma).[1] However, recent studies suggest that solitary osteochondromas represent true benign neoplasms as researchers have identified genetic mutations in the gene encoding exostosin 1 (EXT1).[1][8]

Hereditary multiple exostoses

The hereditary form of the osteochondroma (HME) is associated with a loss-of-function type of mutation in the tumor suppressor genes EXT1 and EXT2 that are responsible for the synthesis of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) which results in HSPG deficiency and subsequent development of multiple osteochondromas.[8] The importance of HSPG in the development of osteochondromas lies in its ability to interact with the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) that have an essential role in the regulation of bone and cartilage formation.[8] HME follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance and a male predominance. There is a broad spectrum of EXT mutations associated with EXT1 and EXT2 genes resulting in HME.[8] In general, patients with EXT1 mutations are more severely affected (more osteochondromas and more severe osseous deformities). Interestingly, even within family members with the same EXT mutations, there is a variable expression of the HME severity suggestion a complex incompletely understood pathophysiology.[8]

Histopathology

Macroscopic gross external examination:

Grossly, osteochondroma is a lobulated sessile or pedunculated lesion arising from the surface of the bone with a somewhat cauliflower-like appearance. The cartilage cap has a shiny glistening bluish to grey appearance. There is a thin fibrous capsule or perichondrium which shows continuity with the periosteum of the underlying bone. The thickness of the cartilage cap of 1 to 3 cm is considered normal in children due to the ongoing growth process. The cartilage cap is either absent or only a few millimeters in thickness in the fully mature skeleton. Cap thickness exceeding 2 cm in an adult should raise suspicion for malignancy. Varying degrees of mineralization may be present within the cartilage cap.[10][11]

Macroscopic cross-sectional examination:

The perichondrium, cortex, and the medulla of the osteochondroma are all continuous with the underlying bone.[10]

Microscopic examination:

Starting from the periphery, the cartilage cap that covers the tumor has a similar histological feature to the growth plate. At the junction of the cartilaginous cap and the underlying bone, evidence of endochondral ossification is visible. The medullary part is usually formed by yellow marrow rather than hematopoietic marrow through the process of endochondral ossification.[10]

History and Physical

Solitary osteochondromas are usually asymptomatic lesions discovered incidentally on radiographs obtained for non-contributory symptoms. Symptomatic lesions may be secondary to fracture, malignant transformation, compression of adjacent neurovascular structures, bursal formation and/or bursitis, or palpable mass. When lesions are symptomatic, cross-sectional imaging is indicated to assess for the previously listed complications. Patients with HME are generally more severely affected and present at a younger age with multiple osseous deformities such as bowing of the extremities, short limbs, short stature, leg length discrepancy, coxa valgus or genu valgus.[1][10]

Evaluation

As previously noted, solitary osteochondromas are generally discovered incidentally on radiographs while patients with HME present with symptoms leading to radiographic evaluation. Osteochondromas involving the long bones (most common location) generally have a pathognomonic appearance and require no further imaging evaluation. On radiographs, the lesions localize to the surface of the bone in the region of the metaphysis, when involving long bones, with medullary and cortical continuity. The lesions may be sessile or pedunculated. When pedunculated, they point away from the adjacent joint. The characteristic cartilage cap is not easily assessable on radiographs. Not surprisingly, lesions in skeletally immature patients may increase in size over time. However, osteochondromas should not enlarge following skeletal maturity. Enlarging lesions in skeletally mature patients is concerning for malignancy. Additional radiographic findings concerning for malignant transformation would include changes in morphology, periostitis, or new indistinctness of the cortical margins. Lesions of the flat bones (scapula, pelvis, spine) are often indeterminant on radiographs and require further imaging to demonstrate the corticomedullary continuity.[1][2][3][5][10]

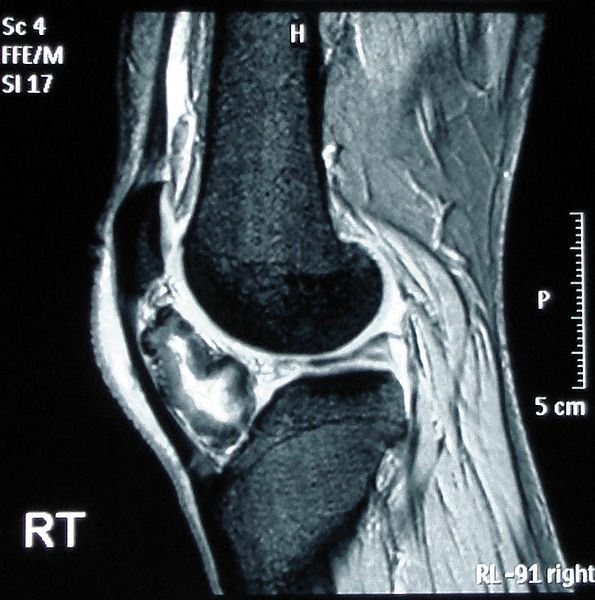

If the patient is symptomatic or demonstrates concerning radiographic features, further evaluation with cross-sectional imaging (MRI, CT, or US) is indicated to assess for potential complications. MRI is ideal for assessing the cartilage cap, which if thickened, may indicate malignant transformation. The cartilage cap will demonstrate intermediate to high signal on T2 and proton density (PD) weighted images. Cartilage caps are generally thicker in skeletally immature patients (range 1 to 3 cm). In skeletally mature patients, the cartilage cap is generally only a few millimeters. Cartilage caps greater than 2 cm, especially in skeletally mature patients are concerning for malignant transformation and require tissue sampling.[1][11]

MRI also offers an exceptional assessment of other complications. Bursae show up well on T2 and PD fat-suppressed images appearing as well defined hyperintense fluid collections with or without bursitis. MRI is also useful to assess displacement and/or impingement on neurovascular structures. In patients with neurologic findings, the involved nerve may be displaced, enlarged, and/or demonstrate a hyperintense T2/PD signal. Additionally, the musculature innervated by the affected nerve may demonstrate edema (acute denervation injury), fatty infiltration (chronic denervation injury) or both. Vascular complications may include pseudoaneurysm formation, compression, or occlusion. The presentation of vascular complications will vary depending on the involvement of arterial or venous structures. In the setting of fracture, MRI will demonstrate bone marrow edema and periosteal reaction. The extent of these findings will vary with chronicity and the extent of healing.[1]

Patients with HME commonly demonstrate bowing deformities of the long bones, short stature, and short extremities. The distribution of the multiple lesions varies in the literature with some authors reporting bilateral symmetric distribution while others report unilateral. The individual lesions are similar to the solitary form with both sessile and pedunculated lesions present. Malignant transformation is more common in patients with HME, and therefore, clinical and imaging surveillance is required.[1]

Bone scintigraphy is generally not helpful as both benign and malignant lesions may demonstrate increased radiotracer activity.[1]

Treatment / Management

Treatment varies from patient to patient. In the solitary form, small asymptomatic osteochondroma without suspicious imaging features requires only follow-up. However, if the lesion becomes symptomatic further assessment with cross-sectional imaging is required. Large, symptomatic lesions or lesions with suspicious imaging features such as growth in a skeletally mature patient, irregular or indistinct margins, focal areas of radiolucency, osseous erosions or destruction require surgical resection. Not surprisingly, excision of pedunculated lesions is easier than sessile lesions. Following resection, there is a 2% recurrence rate reported in the literature. Surgical intervention is much more common in patients with HME owing to both increased risk of malignant transformation and more severe osseous deformities. Surgical intervention may be performed to correct or improve the associated osseous deformities. Patients with HME undergo an average of 2.7 surgical procedures.[1][10][11]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for osteochondroma includes both benign and malignant lesions [1][6][7][10][9]:

- Subungual Exostosis (also referred to as Dupuytren exostosis): This is a common lesion of unknown etiology, thought to arise secondary to prior trauma or infection. The lesions classically arise from the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx near the nail bed. The lesions may be painful with associated skin ulceration. Like osteochondromas, subungual exostosis is a surface lesion. However, there is no medullary continuity. Location is also a key distinguishing feature.

- Dysplasia Epiphysealis Hemimelica (Trevor Disease): This is a rare process with the development of multiple osteochondromas from the epiphysis, most commonly of the lower extremities. There is a 3 to 1 male to female predominance. The process is similar to HME, presenting in young patients secondary to altered gait, osseous deformity or palpable mass. There are no reports of malignant degeneration in the literature.

- Turret Exostosis: Extracortical mass on the back of the middle or proximal phalanx. No medullary continuity.

- Bizarre Parosteal Osteochondromatous Proliferation (Nora lesion): Surface lesion most commonly involving the osseous structures of the hands and feet. Unknown etiology, however, thought to be secondary to prior trauma. The lesion does not have medullary continuity. There is no reported risk of malignant degeneration.

- Parosteal osteosarcoma: Subtype of osteosarcoma arising from the surface of long bones. Radiographs demonstrate a large, lobulated, dense osseous mass without medullary continuity; however, in advance stages, the lesion can infiltrate into the medullary space. Most commonly arises from the metaphysis of the long bones with the posterior margin of the distal femur the single most common location.

- Juxtacortical chondroma: A surface lesion that most commonly results in the saucerization of the adjacent cortex with associated periosteal reaction. More common in patients age 20 to 40.

- Subperiosteal hematoma: A surface lesion with a smooth superficial cortical margin with an elliptical shape arising in patients with a history of prior trauma. There is no medullary continuity. Centrally the lesion may demonstrate heterogeneity with cystic areas, mineralization or fat.

Prognosis

The solitary form has a good prognosis with malignant transformation occurring in 1% of patients. The majority of solitary lesions are small and asymptomatic. Potential complications include fracture, neurovascular impingement, and bursa formation. Symptomatic lesions can undergo excision. Complications of surgical excision include recurrence, neurovascular injury, and compartment syndrome. Reports exist of spontaneous regression of solitary lesions in the literature.[1][12][13]

In patients with HME, reports of the prevalence of malignant transformation are as high as 25%, however, more recent studies suggest 3 to 5%. As previously described, HME patients can have severe osseous deformities, which may affect patients' activities of daily living (ADL).[1]

Complications

Complications of osteochondroma can range from simple cosmetic concern to serious neurological complications and malignant transformation. Complications fall under three categories, including cosmetic deformity, mechanical effect, and malignant transformation.

Cosmetic deformity:

Painless swelling is the most common complaint that triggers patients to seek medical advice due. The osseous deformity is often more severe in HME than solitary osteochondroma.[1][6][10]

Mechanical effect:

An osteochondroma can result in various complications either due to impingement and compression to adjacent neurovascular structures causing neuropathy and vascular insufficiency or due to irritation to adjacent soft tissue leading to the formation of a bursa that could be inflamed and causes pain. Neurological impingement by osteochondroma can have a wide variety of clinical presentations ranging from peripheral neurological symptoms and radiculopathy due to nerve root compression to more serious myelopathy and spinal stenosis depending on the site of the lesion. The presence of osteochondroma can compromise the blood supply to the tissues either by the formation of pseudoaneurysm or by direct compression of the adjacent blood vessels interfering with blood flow. Pseudoaneurysm formation results from the chronic repetitive mechanical compression and friction of the blood vessels by osteochondroma. Not surprisingly since the knee is the most common location of osteochondroma, popliteal pseudoaneurysm and peroneal nerve entrapment are the most common neurovascular complications. Restriction of joint motion, premature osteoarthritis, and osseous deformities affecting ADLs are other possible mechanical complications.[1][6][10][14][15][16]

Malignant transformation:

Malignant transformation is estimated to be 1% in solitary lesions and up to 3 to 5% in HME. An increase in size or change of radiographic appearance as previously described should raise the suspicion of malignancy. Suspicious signs of malignancy on radiograph include surface irregularity, areas of lucency and heterogeneous mineralization, and thick cartilage cap (greater than 2 cm). Chondrosarcoma is the most common form of malignant transformation. However, osteosarcoma has also been reported.[1][6][10][11]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Osteochondroma is a benign bony tumor that has a low risk of malignant transformation with an estimated risk of 1% for solitary lesions and up to 3 to 5% for HME.[1] Osteochondroma is usually asymptomatic and managed with observation. The evaluation mainly relies on conventional radiographs, with MRI reserved for symptomatic patients or lesions involving the flat bones.

Symptomatic osteochondromas management is via surgical excision. Imaging features concerning for malignant transformation should prompt surgical removal or tissue sampling. Since the hereditary form of the bone tumor (HME) carry a higher risk of malignant transformation, regular follow up is necessary.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Osteochondroma is a benign bony tumor that is mainly asymptomatic, and thus usually discovered incidentally. Although management of osteochondroma is the duty of orthopedic surgeons, interprofessional collaboration is a must for providing optimal care to the patient. In fact, initial detection of osteochondroma may be the ER physician, radiologist, nurse practitioner, or family physician either incidentally while investigating for another complaint or while investigating for complaint related to osteochondroma itself. A definitive diagnosis cannot be achieved without the participation of the pathologist and radiologist to confirm osteochondroma and exclude malignant features.

Symptomatic osteochondromas or those that carry suspicious malignant features will require surgery to excise the tumor. Performing any surgical procedure is a great example that demonstrates teamwork and cooperation among different healthcare professions — starting from the pre-operative phase that prepares the patient for the surgery. This phase is mainly the role of anesthesiologists in which they assess the patient's fitness for surgery. The medical team may also be involved in the pre-operative phase either if the patient has any known medical illness, or due to a newly discovered issue during the pre-operative investigation. During the operation, the orthopedic surgeon, anesthesiologist, nurses, and many others will collaborate to perform the surgery. Pharmacists can also weigh in with medication needed for the procedure itself, as well as post-surgical pain control and possible antibiotics, making recommendations to the team and also monitoring for drug interactions and cautioning other team members regarding potential adverse events. Complications associated with osteochondroma may demand the involvement of additional specialty, including a neurosurgeon and vascular surgeon to manage neurovascular complications. Finally, post-operative care and monitoring is an important phase in which both nurses and surgeons who performed the surgery will ensure there are no postoperative complications, and the patent is eligible for a safe discharge. To conclude, diagnosis and management of osteochondroma necessitate the collaboration of different healthcare professions, and achieving optimal care by the orthopedic surgeon alone is an impossible mission.

Osteochondroma diagnosis and management clearly an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, pharmacists, and possibly physical therapists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]