Continuing Education Activity

Vitamin D deficiency accounts for the most common nutritional deficiency among children and adults. Osteomalacia describes a disorder of “bone softening” in adults that is usually due to prolonged deficiency of vitamin D. This results in abnormal osteoid mineralization. This activity describes osteomalacia and its respective causes, clinical presentation, evaluation, and management.

Objectives:

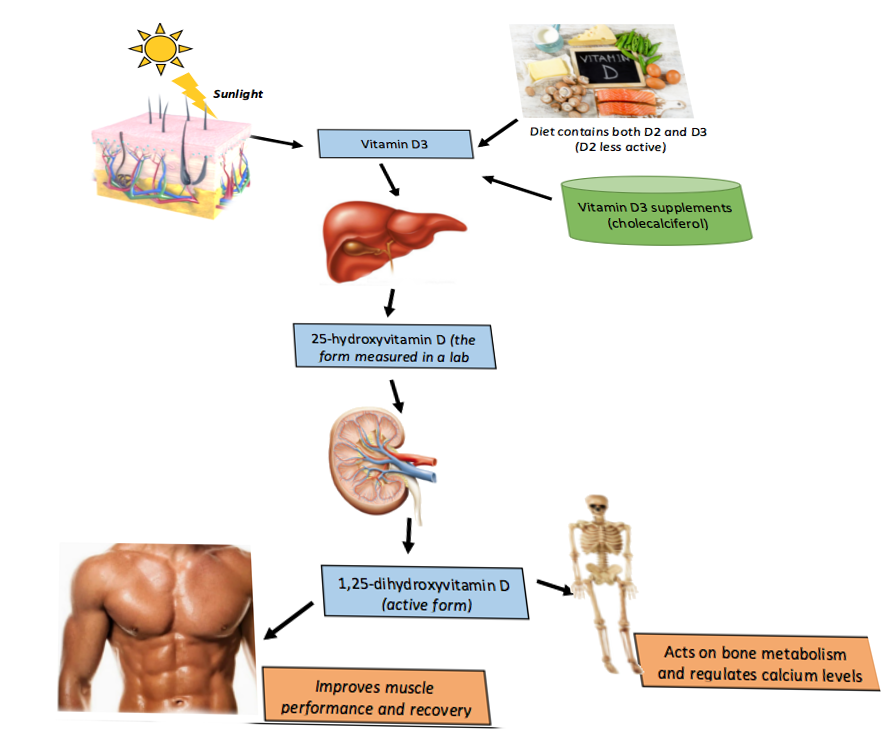

- Summarize the physiology of vitamin D metabolism and associated pathology.

- Identify populations at risk for developing osteomalacia.

- Review presenting symptoms and musculoskeletal manifestations of osteomalacia.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients with osteomalacia.

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency accounts for the most common nutritional deficiency among children and adults. Osteomalacia describes a disorder of “bone softening” in adults that is usually due to prolonged deficiency of vitamin D. This results in abnormal osteoid mineralization. In contrast, rickets describes deficient mineralization at the cartilage of growth plates in children.

Several cell types constitute bone and participate in the coordinated process of bone remodeling. Osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells) are responsible for breaking down bone by secreting collagenase. Osteoblasts are responsible for depositing the osteoid matrix, a collagen scaffold in which inorganic salts are deposited to form mineralized bone. This intricate process is directly and indirectly influenced by hormonal signals, namely parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcitonin, both of which act in response to serum levels of calcium.

In processes that decrease the amount of vitamin D or its bioproducts, normal serum calcium will be maintained by mobilizing calcium from the bones. Specifically, PTH will be secreted by the parathyroid glands in response to hypocalcemia from vitamin D deficiency and will attempt to bring the body back to normal serum calcium levels. Bones are the primary target to recruit calcium, and by extracting calcium from the bones, osteomalacia will ensue. Therefore, adults with processes that disrupt vitamin D metabolism and its production are at risk for eventually developing osteomalacia and its clinical manifestations.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Osteomalacia is a metabolic bone disease characterized by impaired mineralization of bone matrix. Bone creation occurs by the deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals on the osteoid matrix. Below details of the most common and sometimes overlooked causes of this disease are described.

Decreased Vitamin D Production

- Cold weather climates reduce skin sunlight exposure and cutaneous synthesis.

- Dark skin and relatively increased melanin compete with 7-dehydrocholesterol ultraviolet-B (UVB) light absorption.

- Obesity can lead to increased adipose sequestration, which results in less calcidiol substrate available for activation.

- In the elderly vitamin D production decreases, and in general the storage of vitamin D declines with age.

Decreased Vitamin D Absorption

- Nutritional deficiency can cause vitamin D deficiency even with adequate sunlight exposure.

- Malabsorptive syndromes such as Crohn disease, cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, cholestasis, and surgical alteration (i.e., gastric bypass) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are associated with deficient absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K).

Altered Vitamin D Metabolism

- Chronic kidney disease leads to structural damage and loss of 1-alpha-hydroxylase as well as suppressed enzymatic activity secondary to hyperphosphatemia.

- Nephrotic syndrome leads to pathologic excretion of vitamin D binding protein (DBP), which binds to serum calcidiol.

- Liver disease (i.e., cirrhosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) leads to deficient production of calcidiol.

- Pregnancy is associated with decreased levels of calcidiol, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends 1000 to 2000 international units (IU) per day for identified vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women.

Hypophosphatemia or Hypocalcemia

- Renal tubular acidosis such as seen at Fanconi syndrome alters ion absorption and excretion.

- Tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO), also known as oncogenic osteomalacia, is a rare acquired paraneoplastic disease characterized by hypophosphatemia and renal phosphate wasting.

- It is commonly caused by benign tumors involving the skin, muscles, bones of the extremities, or the paranasal sinuses.

Medications

- Anti-epileptic drugs, including phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine, enhance catabolism of calcidiol via induction of P-450 activity.

- Isoniazid, rifampicin, and theophylline also precipitate vitamin D deficiency in this manner.

- Anti-fungal agents such as ketoconazole increase vitamin D requirements by inhibiting 1-alpha-hydroxylase (CYP27B1).

- Long-term steroid use also has implications in vitamin D deficiency, possibly by increasing 24-hydroxylase activity.[4][5][6][7]

Epidemiology

There are citations that the prevalence of osteomalacia histologically at post-mortem is as high as 25% in adult Europeans. The true incidence of osteomalacia, however, remains largely underestimated across the globe. At-risk individuals include those with dark skin, frequent wearers of full-body clothing, limited sun exposure, low socioeconomic status, and poor diet. These risks vary across the world and are contingent on geographic location, cultural preferences, and ethnicity. Healthcare providers should take these factors as well as other relevant clinical findings into account when choosing to obtain further studies or recommend vitamin D supplementation.[8]

Pathophysiology

To understand the pathologic processes that result in vitamin D deficiency and subsequent manifestations, it is first essential to detail vitamin D metabolism.

The synthesis of active vitamin D (calcitriol) organically begins in the skin, where cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is formed by the action of UVB radiation converting 7-dehydrocholesterol (provitamin D3) in epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts to pre-vitamin D, which spontaneously isomerizes to form cholecalciferol.

Subsequently, cholecalciferol gets transported to the liver, where it is converted to calcidiol, 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], by 25-hydroxylase (CYP2R1). Therefore, it is logical that patients with chronic liver disease would be at risk of developing vitamin D deficiency. This particular form of vitamin D is partially water-soluble and has a short half-life. It is worthwhile noting that 25(OH)D is also the best indicator of overall vitamin D status because this measurement most accurately reflects total vitamin D from dietary intake, natural sunlight exposure, and converted adipose stores in the liver. Estimates are that approximately 40 to 50% of circulating 25(OH)D derives from skin conversion.

Enzymatic conversion to calcitriol, 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D [1,25(OH)D], occurs in the kidneys by 1-alpha-hydroxylase. Similarly, chronic renal disease, amongst other renal pathologies, can cause vitamin D deficiency, which is why secondary, and eventually, tertiary hyperparathyroidism can develop with long-term renal failure. It is important to realize that 1-alpha-hydroxylase activity is strictly regulated.

As with any synthetic biologic process, feedback loops exist to regulate calcitriol production, namely:

- Positive feedback by parathyroid hormone (PTH)

- Positive feedback by decreased serum phosphate levels

- Negative feedback by fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) secreted by osteocytes in the bone matrix, which also inhibits renal phosphate absorption

- Negative feedback by calcitriol inhibition of 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which in turn decreases calcitriol synthesis and also stimulates 24-hydroxylase (CYP24R1) activity.

- 24-hydroxylase effectively removes circulating calcitriol by converting it to biologically inactive 24,25-dihydroxy vitamin D [24,25(OH)D].[9]

History and Physical

When evaluating for osteomalacia, a clinical history should include an understanding of a patient's family and surgical (i.e., bypass) history. Other pertinent questions should focus on activity level, hobbies, diet (i.e., vegetarian), and assessment of socioeconomic status.

Symptoms of osteomalacia are non-specific, but may include[10]:

- Proximal muscle weakness and wasting

- Myalgias and arthralgias

- Muscle spasms

- Altered or "waddling" gait

- Spinal, limb, or pelvic deformities (long-term osteomalacia)

- Aching bone pain (lower spine, pelvis, or lower extremities)

- Aggravated by activity and weight-bearing

- Increased falls

- Hypocalcemic seizures or tetany

Evaluation

No single laboratory finding is specific for osteomalacia. However, patients with osteomalacia will usually have hypophosphatemia or hypocalcemia. Additionally, increased alkaline phosphatase activity is typically characteristic of diseases with impaired osteoid mineralization. In fact, some sources believe that either hypophosphatemia or hypocalcemia and increased bone alkaline phosphatase level are necessary even to suspect osteomalacia. As the disease progresses, low bone mineral density (BMD) and focal uptake at Looser zones can appear on bone scintigraphy. Below we describe the findings of definite or possible osteomalacia, as proposed by Fukumoto et al., which requires validation with further studies.[11]

- Hypophosphatemia or hypocalcemia

- High bone alkaline phosphatase

- Muscle weakness or bone pain

- Less than 80% BMD of the young-adult-mean

- Multiple uptake zones by bone scintigraphy or radiographic evidence of Looser zones (pseudofractures)

*Definite osteomalacia defined as all findings.

*Possible osteomalacia defined as having numbers 1, 2, and 2 out of the 3 through 5 findings described above.

The serum level of 25(OH)D is currently regarded as the best marker of vitamin D status and is usually severely low (<10 ng/mL) in patients with nutritional osteomalacia. Other sensitive biomarkers of early calcium deprivation include increased serum PTH and decreased urinary calcium.

Radiographic findings may include Looser zones, or pseudofractures, and this is a classic finding in osteomalacia. They may represent poorly repaired insufficiency fractures and are visible as transverse lucencies perpendicular to the osseous cortex. They typically occur bilaterally and symmetrically at the femoral necks, shafts, pubic and ischial rami. Additionally, radiographs can show decreased distinctness of vertebral body trabeculae due to the inadequate mineralization of osteoid. Although not required for diagnosis, studies have demonstrated reduced bone mineral density in the spine, hip, and forearm.

Iliac crest bone biopsy is considered the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis but should be reserved for when the diagnosis is in doubt, or the cause of osteomalacia is equivocal by noninvasive methods.[11][12]

Treatment / Management

After establishing the diagnosis of osteomalacia, it is crucial to evaluate the etiology.

Treatment should focus on reversing the underlying disorder and subsequently correcting the vitamin D and other electrolyte deficiencies.

When the clinician has determined that vitamin D deficiency is the underlying cause, treatment may lead to significant improvement in strength and relief of bone tenderness in weeks. Serum calcium and urine calcium levels should be monitored, initially after 1 and 3 months, and then every 6 to 12 months until 24-hour urine calcium excretion is normal. Serum 25(OH)D can be measured 3 to 4 months after starting therapy. If hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria is present, the dose can be adjusted to prevent excessive vitamin D dosing. For patients with severe vitamin D deficiency, below is a possible dosing approach:

- 50,000 IU of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) orally one day per week for 8 to 12 weeks, followed by

- 800-2000 IU of vitamin D3 daily

Ergocalciferol is present in plant sources and fortified nutritional alternatives. Cholecalciferol is usually in fish, meat, and eggs. When using vitamin D supplements, accumulating evidence favors the use of cholecalciferol over ergocalciferol because its side-chain has a higher affinity for DPB, thus conferring it a longer half-life and more potent ability to increase vitamin D levels.

Since inadequate calcium intake may have contributed to the development of osteomalacia, patients should also take at least 1000 mg of calcium per day while being treated for the vitamin D deficiency. This dose may need to be increased in patients with malabsorption syndromes, who may also have increased vitamin D dosing requirements. Patients with liver and renal disease will not be able to utilize vitamin D2 or D3 effectively, so calcidiol or calcitriol should merit consideration.[13]

Healing of osteomalacia is achieved when there are increases in urine calcium excretion and bone mineral density. Serum calcium and phosphate may normalize after a few weeks of treatment, but normalization of bone alkaline phosphatase lags behind and those levels may stay elevated for months.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

Depending on the presenting symptoms, the initial differential diagnosis can be extensive. Clinical history, physical exam, lab values, and imaging can narrow the possibilities. However, specific diagnoses present with similar symptoms and lab values and require exclusion. These include metastatic disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, and renal osteodystrophy.

Osteoblastic bone metastases have similar lab findings and may also show multiple zones of uptake by bone scintigraphy. Further evaluation may be warranted to exclude malignancy. Multiple myeloma can present with similar clinical symptoms (i.e., bone pain and weakness), but will often reveal lytic lesions on radiographs. Patients with multiple myeloma may also have anemia and decreased renal function.

Primary hyperparathyroidism should present with hypophosphatemia, increased bone alkaline phosphatase, and increased zones of uptake. However, it usually presents with hypercalcemia, which is atypical in osteomalacia. In renal osteodystrophy hyperphosphatemia, rather than hypophosphatemia, is typically observed.

Prognosis

Osteomalacia is a preventable metabolic bone disorder. As most cases are related to vitamin D deficiency, it can usually be treated appropriately and be cured. If other clinical factors have contributed to the development of osteomalacia, then treatment will need to be tailored and adjusted as necessary.

Once identified and an appropriate treatment plan is in place, lab values may begin to normalize within weeks of initiation. Symptom improvement is also appreciable in a similar period. Patients require interval lab monitoring after starting therapy. Overall, healing of osteomalacia may take many months to a year, depending on the cause.

Complications

Due to poor osteoid mineralization, several complications can occur if osteomalacia is left untreated. Insufficiency fractures, also known as Looser zones, can present as bone pain and occur with little or no trauma. They are typically bilateral, perpendicular to the cortex, and usually involve the femoral neck, pubic and ischial rami. Reports also exist of Looser zones in the ribs, scapulae, and clavicles. Spinal compression fractures are less common and are usually associated with osteoporosis. Researchers have also reported kyphoscoliosis in long-standing osteomalacia.[15]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Certain populations are at greater risk for developing osteomalacia, and the following factors require attention and evaluation:

- Decreased sunlight to skin exposure

- Diet

- Dark skin

- Obesity

- Elderly

- Medications that may precipitate vitamin D deficiency

- Renal or hepatic disease

- Malabsorptive syndromes

Although there is insufficient data to recommend obtaining serum 25(OH)D levels in asymptomatic patients, clinicians should be aware of these factors that may put their patients at risk. It is important to educate patients about these risks and, if possible, how to make tolerable lifestyle changes. In patients who come from more conservative cultures, a vitamin D deficient diet and inadequate direct sunlight exposure may get overlooked by clinicians. Foods with the highest content of naturally occurring vitamin D are usually meat or fish-based. Since patients with vegetarian diets will not consume these foods, it is important to educate them on alternative sources of vitamin D enriched nutrition. These include fortified milk, yogurt, cheese, orange juice, bread, and UVB enhanced mushrooms. The biological significance of consuming these foods requires further assessment.[16][17]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of osteomalacia are best with an interprofessional team. The key is patient education, and thus, all clinicians have a vital role in preventing the high morbidity of the disorder. Fortified foods are those that have been modified to include essential nutrients. In randomized controlled trials, fortified vitamin D foods, including dairy products, bread, orange juice, and UVB enhanced mushrooms, have been shown to be effective at increasing circulating levels of 25(OH)D without adverse side effects. Most countries have individual national policies regarding food enhancement. However, current levels of fortification may not be adequate to satisfy physiologic requirements; this particularly applies to patients already at risk for vitamin D or calcium nutritional deficiencies. Successful enhancement of animal products has also been demonstrated in pigs, hens, and fish by utilizing vitamin D3 enriched feeding. Current results are promising, but further research is necessary on the impact of widespread introduction, particularly in developing countries. Patients need long term follow-up as the resolution can take months. The dietitian and nurses should continue to educate the patient about the importance of a healthy diet, reinforced with vitamin D supplements.[18]

If the treating clinician decides to supplement with exogenous vitamin D, there should be a pharmacist consult to vet the precise agent and assist with appropriate dosing for the condition. Nurses can counsel the patient on administration, and assist in monitoring and evaluating results on followup visits, reporting their findings and concerns to the prescriber. Close communication between interprofessional healthcare team members is vital if one wants to improve outcomes. [Level 5]