Continuing Education Activity

Pediatric spine trauma presents unique challenges due to the anatomical and developmental differences in children compared to adults. One critical aspect is the flexibility and resilience of a child's spine, which can both aid and complicate management. Pediatric spinal injuries are relatively rare compared to adults, but they can have profound consequences if not managed appropriately. Additionally, pediatric patients may not always present with classic signs and symptoms of spinal cord injury, requiring a high index of suspicion for diagnosis.

Treatment strategies for pediatric spine trauma must prioritize preserving spinal alignment, minimizing neurological deficit, and promoting optimal growth and development. Close monitoring and multidisciplinary collaboration are essential throughout the management of pediatric spine trauma. Long-term outcomes following pediatric spine trauma can vary widely depending on the injury's severity and the effectiveness of treatment. Rehabilitation is critical in maximizing functional recovery and quality of life for affected children.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance learners' proficiency in evaluating and managing pediatric spinal trauma. After participation, learners gain a comprehensive understanding of the unique anatomical and developmental characteristics of the pediatric spine, enhancing their ability to interpret radiographic studies to diagnose pediatric spine injuries and associated soft tissue damage. A better grasp of evidence-based management strategies for pediatric spine trauma prepares them to collaborate effectively within an interprofessional team caring for affected patients.

Objectives:

Identify the signs and symptoms indicative of spine trauma in a pediatric patient.

Select appropriate diagnostic tests to evaluate a pediatric patient with suspected spine trauma.

Develop a personalized management plan for a pediatric patient with spine trauma.

Implement interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination to advance the evaluation and treatment of spinal injuries in the pediatric population.

Introduction

A spinal cord injury is a potentially crippling injury that often results in severe and permanent disability. Spinal injury should be highly suspected in young patients with polytrauma. Pediatric spinal injuries are relatively uncommon compared to adults. However, their potential repercussions can be profound if not appropriately managed. One pivotal aspect is the remarkable flexibility and resilience of a child's spine, which can facilitate and complicate treatment approaches. Children's spines undergo significant growth and maturation, rendering them more susceptible to specific injury patterns, such as spinal cord injuries without radiographic abnormalities (SCIWORA). Furthermore, pediatric patients may exhibit atypical spinal cord injury signs and symptoms, necessitating a heightened level of clinical suspicion during assessment.

Up to 5% of patients with a head injury may also have an associated spinal injury, thus the necessity for prompt intervention in such cases. Spinal cord injury involves various levels of the spine. The incidence rates are highest in the cervical region (55%), followed by the thoracic (15%), thoracolumbar junction (15%), and lumbosacral region (15%).[1][2][3][4][5]

Imaging serves as a cornerstone in diagnosing pediatric spine trauma, yet unique considerations must be taken into account to minimize radiation exposure, particularly in children. Sophisticated imaging technologies, eg, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are essential for thoroughly evaluating soft tissue injuries and providing invaluable information about the severity of the damage.

Treatment strategies for pediatric spine trauma necessitate a meticulous approach focused on preserving spinal alignment, mitigating neurological deficits, and fostering optimal growth and development. Early implementation of immobilization techniques, such as cervical collars and spinal precautions, is crucial to prevent further injury during initial stabilization. Surgery may be warranted in cases of significant instability or neurological compromise. Rehabilitation is pivotal in optimizing functional recovery and quality of life for affected children.

Pediatric Spine Anatomy

The spine consists of 5 distinct regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal. Each segment has unique characteristics that influence injury patterns and management strategies.

The cervical spine comprises 7 vertebrae (C1-C7) and supports the head's weight while allowing for a wide range of motion. The first 2 vertebrae, the atlas (C1) and axis (C2), are specialized bones that facilitate head rotation. The pediatric cervical spine is particularly vulnerable to injury due to the relative disproportion between children's head size and neck muscle strength.

The thoracic spine has 12 vertebrae (T1-T12), forming the vertebral column's middle segment. The thoracic vertebrae articulate with the ribs, providing structural support and protection for the thoracic organs. Fractures and dislocations of the thoracic spine are less common in pediatric patients but can occur in high-energy trauma.

The lumbar spine comprises 5 vertebrae (L1-L5) and bears most of the body's weight. The lumbar vertebrae are larger and more robust than those in the cervical and thoracic regions, providing stability and support for activities such as walking and lifting. Injuries to the lumbar spine are relatively rare in pediatric patients but may occur in certain sports or motor vehicle accidents.

The sacral region comprises 5 fused vertebrae (S1-S5), forming the sacrum, which articulates with the pelvis to transmit weight from the spine to the lower extremities. The coccyx, or tailbone, comprises 4 rudimentary vertebrae that provide attachment points for pelvic ligaments and muscles. Injuries to the sacral and coccygeal regions are uncommon in pediatric patients but can occur in direct lower back trauma or falls.

The spinal cord, housed within the vertebral column, extends from the base of the brain to the lumbar spine and is divided into cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal segments corresponding to the vertebral levels. The spinal cord is surrounded by protective meningeal layers, the dura, arachnoid, and pia mater, which help cushion and support the delicate neural tissue.

The 3 most crucial nerve tracts in the spinal cord are the corticospinal (CST) and spinothalamic tracts (STT) and posterior or dorsal column (DC). The CST is a descending motor pathway located in the lateral (LCST) and ventral (VCST) spinal cord regions. Damage to this tract causes ipsilateral clinical findings, including muscle weakness, spasticity, increased deep tendon reflexes, and a Babinski sign. The STT is an ascending pathway that transmits pain and temperature sensations. The STT is located in the anterolateral portion of the cord. Damage to this tract results in loss of pain and temperature sensation on the body's opposite side. The DC are ascending sensory pathways that transmit vibration and proprioception. The DCs are located in the posterior cord region. Damage to one side of the DC causes ipsilateral loss of vibration and position sensation.

Both the STT and DC transmit light touch. This sensation may be preserved after a spinal cord injury unless the STT and DC are simultaneously involved.

Due to ongoing growth and development, pediatric patients exhibit unique vulnerabilities in their spinal anatomy. Cartilaginous growth plates (epiphyseal plates) at the long bones and vertebral bodies' margins render pediatric spines more susceptible to certain injury patterns, such as physeal fractures. Additionally, the ligamentous laxity and increased flexibility of pediatric spines may predispose children to specific injuries, such as SCIWORA, requiring a high suspicion index for diagnosis.

Etiology

The causes of spinal cord injuries are varied, but most are due to blunt trauma. Motor vehicle accidents are a leading cause of spinal cord injury, followed by falls, particularly in children younger than 8. Sports-related injuries become more common with developmental progression. Firearm injuries and other forms of violence in adolescents and young adults may also result in spinal cord injuries. Neonatal birth trauma can also damage the spine.[6][7]

Epidemiology

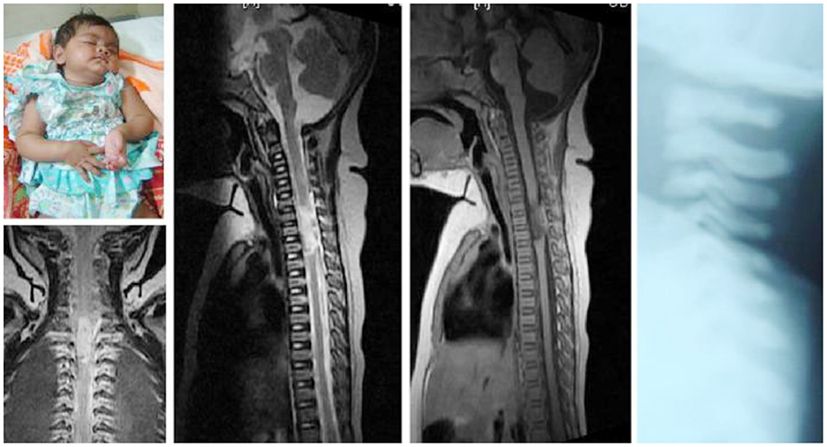

The annual incidence of spinal cord injury is approximately 40 cases per million population. Adolescent boys are at the highest risk for spinal injuries. Nonaccidental injuries are underreported. Therefore, the true incidence of spinal injuries is underestimated. A study found that atlantoaxial injuries are 2.5 times more common in children than adults (see Image. Atlantoaxial Dissociation Radiography).[17]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of pediatric spinal injury differs markedly from that of adults. The pediatric spine differs from the adult spine in the following aspects:

- Children have a different cervical fulcrum compared to adults due to their disproportionately large heads.

- Children's vertebrae are incompletely ossified.

- Children's ligaments are firmly attached to more horizontal articular bone surfaces.

Spine flexibility inversely correlates with age. Hence, neural damage is more likely to occur than musculoskeletal injury in children. The likelihood of cervical cord injury decreases with increasing age. Up to 75% of spinal cord injuries occur from infancy to 8 years of age because the cervical mobility fulcrum moves progressively downward with the child’s increasing age.

- Younger than 8 years: C1 and C3

- At ages 8 to 12 years: C3 and C5

- Older than 12 years: C5 and C6

The mode of injury is classified as either primary or secondary. A primary injury results from mechanical forces directly from trauma. A secondary injury occurs due to a primary injury's vascular and chemical sequelae.

Spine trauma may give rise to spinal cord syndromes. The most common ones are explained below.

Central Cord Syndrome

The CST demonstrates organized lamination, with the sacral components located most laterally and progressing medially upward through the lumbar, thoracic, and cervical components toward the central spinal canal. Central cord syndrome is the most common incomplete spinal cord injury, arising when middle cord damage is greater than lateral cord injury.

Central cord syndrome symptoms are related to the CST's somatotopic organization within the spinal cord. The condition manifests as symmetric incomplete quadriparesis. Disproportionately greater motor impairment is seen in the upper than the lower extremities, along with bladder dysfunction and a variable degree of sensory loss below the level of injury. The typical mechanism involves a hyperextension injury. Research suggests that injury in central cord syndrome predominantly involves the white matter.

Anterior Cord Syndrome

This condition arises from damage to the spinal cord's anterior two-thirds, injuring the CST and STT. Anterior cord syndrome is characterized by total motor paralysis and the absence of pain and temperature sensation. Proprioception and vibration sensation are preserved. More significant motor impairment is observed in the lower than the upper extremities. Proprioception and vibration are spared because the posterior third of the spinal cord containing the DC is not involved. This condition has a poor prognosis, with only 10% to 15% of patients demonstrating functional recovery. The typical mechanism is hyperflexion and axial loading.

Brown-Séquard Syndrome

This condition arises from lateral spinal cord hemisection, frequently from penetrating trauma in the cervical spine. The descending lateral CST and ascending DC are disrupted. The tracts decussate in the medulla, resulting in ipsilateral hemiplegia and ipsilateral loss of proprioception, respectively. Thus, Brown-Séquard syndrome is characterized by ipsilateral hemiplegia, ipsilateral loss of proprioception, and contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensations.

Posterior Spinal Cord Syndrome

This condition arises from posterior spinal cord injury, either from direct trauma or secondary posterior spinal arterial damage. This type of injury is characterized by reduced proprioception and vibration sensations below the level of the injury, but motor function and pain and temperature sensations are spared.

Posterior spinal cord syndrome is associated with neck hyperextension. Patients with this condition may ambulate but require visual guidance of their feet due to loss of proprioception and vibratory sensations, limiting their ability to walk in the dark.

Cauda Equina Syndrome

The cauda equina contains lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal nerve roots. Damage to this spinal cord segment may cause pelvic and lower extremity neurologic deficits, including bowel or bladder dysfunction, decreased rectal tone, asymmetric lower extremity sensory loss, lower extremity weakness, decreased lower extremity reflexes, and saddle anesthesia, characterized by sensory deficit over the perineum, buttocks, and inner thigh. Cauda equina syndrome arises from an indirect spinal cord injury. These neurologic manifestations warrant emergency neurosurgical intervention.

Spinal Shock

This condition presents as a sudden loss of reflexes and muscle tone below the injury level following an acute spinal cord injury. During spinal shock, patients appear physiologically paralyzed but may recover significantly once the initial phases resolve.[8]

History and Physical

History

Patients with trauma may present unconscious, pulseless, and apneic. Cardiorespiratory arrest warrants immediate resuscitation regardless of cause. A quick primary survey should include airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure. Once stable, a more exhaustive investigation may be initiated.

Symptoms and signs commonly observed in pediatric spinal trauma vary depending on the injury's severity and location. Children may experience localized pain at the injury site, ranging from mild to severe. The pain may worsen with movement or spinal palpation. Limited spine range of motion may be observed, particularly in the affected area. Children may resist movement or experience pain with attempts to bend, twist, or rotate the spine. Severe spinal trauma may cause visible deformity.

Difficulty walking or standing upright may be due to pain or neurological impairment. Young patients may exhibit an abnormal gait or prefer to remain seated or lying to alleviate discomfort. Neurological symptoms such as weakness, numbness, tingling, urinary retention, or incontinence may be reported. Older children are more likely to report paresthesias. Persistent headaches or neck pain exacerbated by movement or certain positions may be elicited. Loss of consciousness may indicate head trauma and warrant evaluation for concomitant spinal cord injury.

Severe spinal trauma involving the cervical or thoracic spine can lead to respiratory compromise. Respiratory issues may indicate potential spinal cord lesions or associated injuries to the chest wall or respiratory muscles.

Pediatric patients with spinal trauma may have concomitant injuries in other body sites. Emergency conditions, such as open fractures, neurovascular compression, and hemorrhage, must be quickly ruled out or addressed if present.

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination is warranted in young patients with trauma, especially if multiple injuries are suspected. Tachycardia with hypotension may indicate severe bleeding. Abnormal respiratory rate and oxygen levels may signify concomitant pulmonary injury. Skin examination may reveal open wounds, abrasions, or contusions. Signs of head injury like scalp lacerations, bruising, or skull deformities should be examined. Cervical spine tenderness and range of motion also warrant assessment. Chest and abdominal examination may reveal chest wall tenderness, abnormal breath sounds, bruising, crepitus, and abdominal tenderness. A pelvic inspection may reveal bruising, bleeding, and bone dislocation.

Musculoskeletal assessment may reveal fractures, dislocations, and soft tissue injuries. Peripheral pulses, capillary refill, and neurovascular status should be evaluated to detect vascular compromise or compartment syndrome.

A comprehensive neurological assessment is necessary, including evaluation of mental status, cranial nerve function, motor strength, sensation, and reflexes in all extremities to identify signs of spinal cord injury or neurologic deficits. The following steps should be included in the neurological examination:

- Determine the mental status using the Glasgow Coma Scale score.

- Attempt to delineate the level of the spinal cord injury or level of sensory loss.

- Test for proprioception or vibratory function to examine posterior column function.

- The anogenital reflexes should be tested. Intact anogenital reflexes signify an incomplete spinal cord injury. This evaluation should include the bulbocavernosus, anal wink, and cremasteric reflexes, and rectal tone.

- A careful evaluation of the entire spine should be performed if a cervical injury is detected. Spinal palpation may elicit tenderness.

- A serial neurologic examination documents neurologic improvement or deterioration in patients with suspected or diagnosed spinal injuries.

The American Spinal Injury Association classifies spinal cord injury into complete spinal cord injury, which includes the complete absence of sensory and motor function below the level of injury, and incomplete spinal cord injury, in which a patient has partial sensory or motor function or both below the neurologic injury level. However, this distinction may not be possible until spinal shock has resolved, as patients in spinal shock may lose all reflexes below the area of injury. Notably, young patients with cervical and high thoracic spinal cord injuries are at risk for respiratory failure and neurogenic shock.[9][10]

Evaluation

A combination of imaging tests and clinical assessment is used to diagnose and evaluate pediatric spine trauma comprehensively. Radiography, computed tomography (CT), and MRI are the recommended diagnostic modalities for evaluating pediatric spine trauma, as explained below.

Plain Radiographs

The cervical spine's lateral, anteroposterior, and odontoid views are recommended in alert patients. An adequate lateral cervical spine x-ray typically includes all 7 cervical vertebrae and the superior T1 border. An adequate lateral cervical spine film can identify up to 90% of bony injuries. Decision rules help determine the necessity of cervical spine imaging if physical examination alone cannot detect cervical spine injuries.

National emergency x-radiography utilization study (NEXUS)

NEXUS includes 5 clinical criteria that determine whether cervical spine imaging is warranted. Imaging may not be necessary if the patient presents with the following:

- No midline cervical tenderness

- Normal level of consciousness

- No evidence of intoxication

- No focal neurologic deficit

- No distracting injury, eg, open fracture

Although no validated prediction rule exists for cervical spine imaging in children, clinical features that warrant imaging include altered mental status, focal neurologic finding, neck pain, torticollis, significant torso injury, underlying condition predisposing to spinal cord injury (eg, Down syndrome, Klippel-Feil syndrome), diving and high-risk mechanisms such as acceleration or deceleration injury. The spine should remain immobilized until the clinician reliably excludes injuries if the initial radiographs are inconclusive.

CT Scan

CT scanning is highly sensitive and specific for evaluating the cervical spine, particularly at the craniocervical and cervicothoracic junctions, where plain films' sensitivity is limited. The scan should be obtained in unconscious patients with significant blunt trauma. However, whether a negative CT scan in an unconscious patient suffices or if a subsequent MRI is warranted is unclear. Notably, the absence of radiographic abnormality cannot exclude injury, particularly in children. Spinal cord stretching can cause SCIWORA in patients younger than 8. This injury is likely caused by the facet joints' horizontal orientation and elastic intervertebral ligaments, resulting in upper cervical spinal elements shifting rather than breaking under force.[11][12][13]

MRI

MRI is widely regarded as the most sensitive imaging method for detecting spinal cord and ligamentous injuries, particularly in pediatric patients who are vulnerable to SCIWORA (see Image. SCIWORA on MRI). Gradient-echo MRI sequences can effectively identify spinal cord hemorrhage. In contrast, proton-density-weighted or T2-weighted MRI sequences provide better visualization of structures like the tectorial membrane, alar ligaments, and transverse ligaments. Studies have revealed that approximately 24% of children with cervical spine clearance exhibit occult injuries detectable by MRI. However, obtaining MRI in young children may be limited by longer imaging times and the necessity for sedation, which may not be universally available.

Treatment / Management

The management of pediatric spine trauma involves a coordinated approach to stabilize the patient, assess for spinal cord injury, and provide appropriate interventions to prevent further damage and promote recovery. Early recognition, prompt intervention, and comprehensive interprofessional care are essential for optimizing outcomes in pediatric spine trauma patients. The different aspects impacting the acute management of this condition are explained below.

Prehospital Setting

Immediate goals in the prehospital management of pediatric spine trauma are the following:

- Recognition of patients at significant risk for spinal cord injury

- Cervical spine immobilization

- Triage to an appropriate facility

First responders should facilitate seamless communication and coordination with in-hospital care teams, ensuring a smooth transition of care and optimizing the delivery of medical interventions upon arrival at the hospital.

Emergency Department

Pediatric spine trauma may result in severe morbidity and mortality. A quick primary survey must be conducted to evaluate and address the following:

- Airway: Airway maintenance and cervical spine protection must be established. Indications for intubation include altered mental status, craniofacial trauma, and respiratory failure.

- Breathing: Oxygen supplementation and ventilation must be provided if the patient presents with respiratory distress.

- Circulation: Intravenous access must be established immediately, especially since some patients with spine trauma are vulnerable to neurogenic shock. Bleeding sources must be identified and controlled.

- Disability: A quick, focused neurologic evaluation must be performed.

- Exposure: The patient must be fully exposed to look for hidden injuries. Extremes of temperature must be addressed.

The priority is to protect the airway. Notably, the higher the level of spinal injury, the greater the likelihood of requiring early airway intervention. Injuries above C3 carry a risk of immediate respiratory arrest. Additionally, injuries affecting C3 to C5 can impact phrenic nerve and diaphragm function. Endotracheal intubation must be considered early if injury at or above the C5 level is sustained.

Inline spinal stabilization should be maintained during intubation. Vital signs must be monitored, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory status, and temperature. Capnography may be useful in monitoring respiratory status, particularly in the emergency department.

Neurogenic shock should be suspected if hypotension is present in patients with spinal cord injury. Hypotension and relative bradycardia are the typical manifestations. However, blood loss should be suspected if hypotension is present in patients with spinal injury patients. Importantly, systolic blood pressure of less than 80 mm Hg is rarely due to neurogenic shock alone. A careful evaluation should be performed to search for the source of bleeding if a spinal cord injury is present. Hemorrhagic shock may coexist with neurogenic shock.

Trauma protocols must be activated early in patients showing signs of severe distress or multiple injuries. Early referrals to pediatric orthopedic surgery, neurology, and neurosurgery must be considered.

Corticosteroid use

Clinicians have treated patients with blunt spinal cord injuries with high-dose methylprednisolone. The National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS) demonstrated improved neurologic function in patients who received high-dose corticosteroids within 8 hours of injury. A loading dose of 30 mg/kg of methylprednisolone was administered over 15 minutes. An infusion of 5.4 mg/kg/hr was then started and continued for 24 hours in patients treated within 3 hours of injury or 48 hours in patients treated 3 to 8 hours after injury. Administering steroids 8 hours or more after injury did not demonstrate any benefit. Steroids are not indicated for penetrating injuries as they are not adequately studied in children under 13 years of age. Steroids may cause gastrointestinal hemorrhage, wound infection, severe sepsis, and severe pneumonia.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis should include the following:

- Nonaccidental trauma: Spinal trauma may be accompanied by other severe injuries, eg, spiral limb fractures.

- Malignancy: The patient may have constitutional symptoms, a positive family history, or a congenital condition predisposing to malignancies.

- Infection: The patient may have febrile episodes and risk factors, such as open fractures and recent surgery. Tuberculosis of the spine should be suspected in at-risk patients, eg, immunocompromised and migrants from endemic countries.

The following conditions must be ruled out after a spinal injury:

- Acute torticollis

- Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndromes

- Cervical strain

- Hanging injuries and strangulation

- Neck trauma

- Spinal cord infections

- Spinal cord injuries

A thorough clinical evaluation and judicious diagnostic testing can help determine the correct diagnosis and appropriate management strategies for young patients with spinal trauma.

Prognosis

The severity of spinal cord injury significantly influences the prognosis for recovery of function. Incomplete lesions have a better prognosis compared to complete injuries. Only 10% to 25% of patients fully recover after complete spinal cord injuries, while 64% percent show partial recovery.[14] Children who sustained spinal trauma before their growth spurt can develop scoliosis secondary to cord injury. Neurological injury has a better prognosis in children compared to adults.

Complications

The following complications may occur following a spinal cord injury:

- Spinal shock

- Neurogenic shock

- Loss of bowel and bladder control

- Bedsore

- Pneumonia and atelectasis

- Urinary infections

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Scoliosis

- Syringomyelia

- Hip instability

Prevention of complications associated with spinal cord injury involves early recognition and appropriate management, including fracture immobilization, respiratory support, and prophylactic measures such as turning and repositioning to prevent bedsores and pneumonia. Additionally, comprehensive rehabilitation programs focusing on muscle strengthening, mobility training, and bladder and bowel management can reduce the risk of developing these conditions postinjury.

Consultations

Referral to pediatric orthopedics, neurology, and neurosurgery is crucial in managing pediatric spinal trauma. Pediatric orthopedic specialists can assess and treat fractures and spinal deformities unique to children, ensuring stabilization of spinal injuries and preventing complications. Pediatric neurologists evaluate neurological deficits and monitor neurological function over time, providing essential insights into the extent of spinal cord injury and guiding rehabilitation efforts to maximize functional recovery. Pediatric neurosurgeons manage complex spinal cord injuries and other neurosurgical emergencies, performing surgical interventions when indicated. Collaborating with these specialized teams ensures comprehensive evaluation and tailored management plans for pediatric patients with spinal trauma.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Primary prevention strategies for pediatric spine trauma focus on reducing the risk of injuries before they occur. Education is crucial in primary prevention efforts for children and their caregivers. Teaching children the importance of safe behavior, such as wearing helmets while biking or participating in sports, and avoiding risky activities can help minimize the risk of spinal injuries. Similarly, educating parents and caregivers about child safety measures, such as properly using car seats and seat belts, can help prevent spinal trauma in motor vehicle accidents.

Secondary prevention strategies aim to reduce the severity of injuries and their associated complications once they have occurred. Prompt identification and appropriate management of potential risk factors, such as sports-related injuries or motor vehicle accidents, are essential for secondary prevention. Appropriate measures include implementing safety protocols in sports activities, such as proper technique training and wearing protective gear, to reduce the risk of spinal injuries. Additionally, ensuring rapid access to medical care and appropriate diagnostic imaging can help identify and treat spinal injuries early, potentially preventing further damage and complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pediatric spinal trauma poses distinct clinical challenges because of the pediatric spine's continuous development and dissimilarities with the adult spine. A high suspicion index for spinal cord injuries must be maintained in these patients, as symptoms and signs may be subtle or nonspecific. Prompt recognition and appropriate management are paramount to prevent long-term complications. Imaging, particularly MRI, is critical to diagnosis, given the potential for SCIWORA in this population. Treatment strategies prioritize spinal alignment preservation and minimizing neurological deficits while considering the child's developmental stage. Interprofessional collaboration is essential for tailored management plans that address individual needs.

Prevention of complications in pediatric spinal trauma involves early recognition and intervention of potential risks. Prophylactic measures such as immobilization, respiratory support, and comprehensive rehabilitation programs focusing on muscle strengthening, mobility training, and bladder and bowel management are vital. Implementing preventive strategies early in the management process can significantly improve outcomes and reduce the burden of long-term complications for pediatric patients with spinal trauma.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The interprofessional approach is indispensable in managing pediatric spinal trauma due to the complexity and multifaceted nature of these cases. Following the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol and assessing the patient for secondary injuries comprise the initial steps in managing pediatric patients with possible spinal injuries. Trauma surgeons and emergency clinicians are often the first responders in the hospital setting, providing immediate stabilization and assessment of the child's condition. Neurologists and neurosurgeons bring expertise in evaluating and managing neurological deficits and spinal cord injuries, while orthopedic surgeons specialize in assessing and treating spinal fractures and deformities.

Radiologists contribute to the diagnostic process through imaging interpretation, guiding treatment decisions. Intensivists manage critically ill patients, providing intensive care support and monitoring for complications. Nurses and rehabilitation therapists provide ongoing care, support, and rehabilitation services to optimize functional recovery and quality of life. Effective communication and collaboration among these specialists ensure a comprehensive and coordinated approach to pediatric spinal trauma management, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Most patients are treated with supportive care after spinal trauma has been diagnosed. The outlook of children is significantly better than that of adults, but the recovery can be prolonged. Individuals with severe neurological deficits at presentation may have residual deficits after full recovery.[15][16]