Introduction

Two types of movements occur in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract; peristalsis and segmentation. Peristalsis is the involuntary contraction and relaxation of longitudinal and circular muscles throughout the digestive tract, allowing for the propulsion of contents beginning in the pharynx and ending in the anus. Swallow-induced peristalsis is termed primary peristalsis, while peristalsis evoked by distension of the esophagus is termed secondary peristalsis. While peristalsis propels contents forward, segmentation is the mixing of these contents, both of which play an essential role in allowing for the absorption of water and nutrients.[1]

The GI tract is innervated by the enteric nervous system (ENS), a division of the peripheral nervous system, which controls the GI system independent of any central nervous system (CNS) input. The ENS consists of two networks of nerves, the myenteric plexus (Auerbach plexus) and the submucosal plexus (Meissner plexus). The myenteric plexus is situated between the longitudinal and circular muscles of the GI tract and contains the pacemaker cells of the GI tract and the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC). The myenteric plexus and ICC mediate the process of peristalsis by alternating between distal relaxation and proximal contraction of the muscles.[2]

Issues of Concern

Effective peristalsis requires an active myenteric plexus. Depression or complete blockade of peristalsis can be seen in the congenital absence of the myenteric plexus, termed Hirschsprung disease, or by utilizing atropine to paralyze the cholinergic nerve endings of the myenteric plexus. Alterations in the function of peristalsis have also been implicated in motility disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), gastroparesis, and achalasia.[3] Furthermore, studies have demonstrated a decrease in esophageal peristalsis as individuals age due to age-related GI mucosal and muscular atrophy.[4]

Cellular Level

The walls of the GI tract are composed of four layers of tissue, from innermost to outermost: mucosa (epithelium, lamina propria, and muscular mucosae), submucosa, muscularis propria (inner circular muscle, outer longitudinal muscle), and the serosa.

The smooth muscles responsible for movements of the GI tract are arranged in two layers; an inner circular and an outer longitudinal layer. Between these two layers of smooth muscle lies the myenteric plexus, a network of nerves containing the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC).[5]

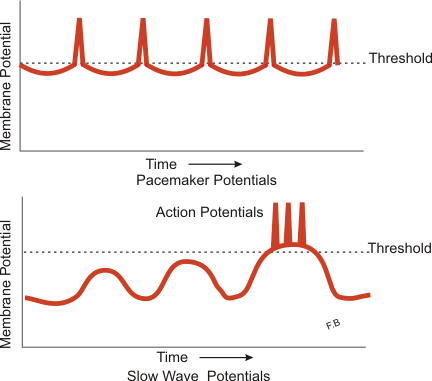

The ICC are considered the pacemaker cells of the GI tract, responsible for generating and actively propagating slow waves. Slow waves are partial depolarization in smooth muscle that, due to the syncytial nature of the cells, sweep down long distances of the digestive tract. Depolarization of smooth muscle cells occurs via the activation of an inward current carried by L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels. Activation of L-type calcium channels is a primary mechanism through which GI smooth muscle cells achieve excitation-contraction coupling. Calcium entry into smooth muscle cells through L-type calcium channels during action potentials (AP) is substantial. When an AP occurs in phasic GI muscles, they are superimposed upon slow-wave depolarization. This mechanism shows the syncytial nature between smooth muscle cells and ICC: ICC generates slow waves which conduct into smooth muscle cells, depolarizing them. The depolarization of the smooth muscle cells then elicits action potentials.

It is important to note that slow waves are not action potentials and do not elicit contractions by themselves. Slow waves synchronize muscle contractions in the gut by controlling the appearance of a second depolarization event, spike potentials, which occur at the crest of slow waves. Spike potentials are true GI APs that elicit muscle contraction. Slow-wave frequency differs throughout the GI tract, occurring approximately 16 times per minute in the small intestine and roughly three times per minute in the stomach and large intestine.[6]

Peristalsis occurs in both the smooth muscle esophagus and the skeletal muscle esophagus. Peristalsis in the skeletal muscle esophagus results from the activation of neurons at the level of the vagal nucleus (nucleus ambiguus). In contrast, peristalsis in the smooth muscle esophagus is mediated by the vagus nerve at the level of the dorsomotor nucleus and myenteric plexus.[7]

Chemically, intestinal serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) is critical in the modulation of ENS development, motility, secretion, sensation, epithelial growth, and inflammation. Upon its release, 5-HT binds to specific receptors, 5-HT3 and 5-HT4, present on neurons within the myenteric plexus of the ENS. Stimulation of 5-HT3 receptors results in the activation of afferent nerves. In contrast, stimulation of 5-HT4 receptors augments peristaltic reflex pathways by acting presynaptically on nerve terminals to enhance the release of acetylcholine, thus, stimulating peristalsis.[8]

Development

Gastric peristalsis has been observed in the human fetus as early as 14 weeks of gestation, with all normal developing fetuses exhibiting sporadic gastric peristalsis by 23 weeks of gestation. At 24 weeks, fetal peristalsis increases in strength and duration up through weeks 32-35 of gestation, after which time the duration of peristaltic episodes remains constant.[9]

Organ Systems Involved

Gastrointestinal peristalsis involves the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and rectum. The peristaltic movement of smooth muscle may also be found elsewhere throughout the body, including within the ureters, vas deferens, bile ducts, and glandular ducts.

Lymph circulates throughout the human body via multiple mechanisms, including arterial pulsation, compression of lymphatic vessels during skeletal muscle contraction, and peristalsis within the lymph capillaries.[10]

Uterine peristalsis is a mechanism that directs sustained and rapid sperm transport from the external cervical os to the isthmus ipsilateral to the dominant follicle. This action of peristalsis changes direction and frequency throughout the menstrual cycle, with its activity lowest during menstruation and highest during ovulation.[11]

Function

The function of peristalsis within the small intestine is three-fold: (1) the mixing of contents with intestinal and exocrine secretions, (2) uniformly and evenly exposing contents to the mucosal surface of intestinal cells, and (3) propelling contents distally into the large intestine at a rate that allows for optimal absorption and digestion.[12]

The function of peristalsis within the colon is to mix, store, and slow the transportation of intestinal contents and to aid in the rapid evacuation of feces. While peristaltic waves in the small intestine are frequent, peristaltic waves within the large intestine occur approximately 2 to 4 times daily and are most substantial in the hour following a meal.[13]

Mechanism

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) stimulates peristalsis via the myenteric plexus. The afferent (sensory) nerves of the myenteric plexus deliver information to interneurons within the plexus. Interneurons communicate with efferent nerves, stimulating an action potential (spike-wave) within smooth muscle cells. The afferent nerves are stimulated by two mechanisms: (1) reflexive (stretch or chemoreceptors) or (2) parasympathetic stimulation (via acetylcholine).

The smooth muscle cells responsible for peristalsis include the inner circular and outer longitudinal layers of muscle, collectively called the muscularis propria. Reflexive stimulation of afferent nerves begins when a food bolus causes stretch within the intestines. The efferent signal causes the inner circular muscles just before the bolus to contract and push the bolus forward while also causing the outer longitudinal muscles to contract and shorten the tube. At the same time, descending inhibitory reflexes cause the circular muscles just beyond the bolus to relax, allowing for forward movement of the bolus. The bolus moves a few centimeters during each peristalsis wave, and the process starts over again.[14]

Two types of peristalsis occur within the esophagus: primary and secondary. Primary esophageal peristalsis is a continuation of pharyngeal peristalsis, initiated by swallowing, and acts to move contents from the esophagus into the stomach. Should primary peristalsis fail to move the entirety of the bolus into the stomach, distension of the esophagus will initiate secondary esophageal peristalsis until all contents are cleared.[15] Secondary peristalsis can be physiologically triggered by various intraesophageal stimuli, including air, mechanical distention, or water infusion. Primary peristalsis is coordinated by the swallowing center in the medulla and cannot occur after vagotomy. In contrast, secondary peristalsis involves the ENS and can function independently of CNS input, allowing for continued function postvagotomy.[16]

Related Testing

Motility disorders involving peristalsis may be tested by esophageal, antroduodenal, colonic, and anorectal manometry.[17] Esophageal high-resolution manometry is the current state-of-the-art tool to visualize esophageal motility patterns. 24-hour pH impedance testing utilizes a flexible catheter with a pH-sensitive tip to evaluate acid and non-acid reflux, which can aid in diagnosing peristaltic disorders, such as GERD.[18] A barium swallow (esophagogram) helps detect diseases of the upper GI tract that may cause, or be caused by, peristaltic dysfunction.[19]

Pathophysiology

As previously discussed, the slow waves initiated by ICC result in the depolarization of L-type calcium channels and, ultimately, the contraction of smooth muscle cells. ICC are both chronotropic and inotropic, regulating the strength of the contractile response. Currently, motility disorders associated with ICC dysfunction are at the forefront of research, especially concerning motility pathologies such as Hirschsprung disease, gastroparesis, and achalasia.[20]

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

GERD occurs when stomach acid or contents flow back into the esophagus, irritating its lining and potentially causing heartburn. Transient lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation, hypotensive LES, bolus transit abnormalities, and ineffective esophageal peristalsis are strongly implicated in developing GERD. Under normal circumstances, the LES contracts after the passage of food, preventing reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, and esophageal peristalsis clears refluxate back into the stomach. Impairment of the LES or dysfunctional esophageal motility contributes to the pathology of GERD.[21]

Hirschsprung Disease

During the first 12 weeks of gestation, craniocaudal migration of neuroblasts originating from the neural crest occurs. Cells from the neural crest migrate to the colon to form the myenteric and submucosal plexus. In Hirschsprung disease (also called congenital aganglionic megacolon), there is a defect in this migration, causing the distal colon to lack the necessary nerve bodies to regulate colonic activity. In turn, the colon cannot relax or pass stool, creating an obstruction.[22] Trisomy 21 is a predisposing factor to Hirschsprung disease, and treatment requires surgical resection of the affected colon.[23]

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis is a chronic disease with three known subclasses: diabetic, idiopathic, and postsurgical gastroparesis. Clinical symptoms of gastroparesis include nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, and abdominal pain. These symptoms, in conjunction with an objective finding of delayed gastric emptying and a documented absence of gastric outlet obstruction, are required for diagnosis. The pathophysiology behind gastroparesis is complex, with ongoing research; however, full-thickness gastric biopsies of individuals affected by gastroparesis found decreased ICC cells. This decrease in ICC cells leads to a lack of communication between smooth muscle cells, thus causing peristaltic dysfunction. In cases of diabetic gastroparesis, chronically elevated blood glucose levels can lead to neuronal damage, affecting the myenteric plexus and, therefore, peristalsis.[20]

Achalasia

Achalasia is a motility disorder characterized by impaired relaxation of the LES and the absence of esophageal peristalsis. The classic presentation of achalasia includes dysphagia to solids and liquids and regurgitation of saliva or undigested food. Many studies suggest an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons of the myenteric plexus causes the neuronal cause of achalasia. Studies have shown that absent or abnormal inhibitory innervation in achalasia is due to extrinsic or intrinsic causes. Extrinsic causes include CNS lesions involving the dorsal motor nucleus or vagal nerve fibers, while the intrinsic loss may be due to the loss of inhibitory ganglionic cells within the myenteric plexus.[24]

Retroperistalsis (Vomiting)

Pathologically, retroperistalsis is the forceful removal of gastrointestinal contents due to diverse emetic stimuli. The reversal of peristalsis typically begins in the small intestine (duodenum) and continues up through an open pyloric sphincter. Retroperistalsis occurs not only pathologically to initiate vomiting but physiologically as well. Physiologic retroperistalsis occurs at the level of the duodenum to protect GI mucosa from acidic stomach contents and at the terminal ileum to allow for maximum absorption of water and nutrients.[25]

Clinical Significance

Symptoms of peristalsis dysfunction, such as dysphagia, chest pain, heartburn, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea, can mimic severe, life-threatening disorders. Therefore, understanding the physiology and pathophysiology of peristalsis is essential to distinguish between emergent and non-emergent ailments.

Most medications prescribed today are accompanied by gastrointestinal side effects, many of which alter the action of peristalsis. Knowing and understanding these side effects is vital to ensure appropriate medication administration. Beyond medications with GI side effects, there are medications prescribed that inhibit peristalsis, as in treatments for diarrhea, and those that stimulate peristaltic contractions to treat constipation.