Introduction

Post-void residual volume (PVR) is the amount of urine retained in the bladder after a voluntary void and functions as a diagnostic tool. A PVR can be used to evaluate many disease processes, including but not limited to neurogenic bladder, cauda equina syndrome, urinary outlet obstruction, mechanical obstruction, medication-induced urinary retention, postoperative urinary retention, and urinary tract infections.

The PVR may be determined via urinary catheterization, a portable dedicated bladder scanner, or a formal ultrasound examination.

When used in conjunction with the American Urological Association (AUA) Symptom score and a 24-hour voiding diary, the PVR can provide the clinician with a clear picture of the patient's bladder activity, functionality, and correlation with symptoms leading to an evidence-based diagnosis which then guides appropriate directed therapy.

Specimen Collection

A urine specimen is not always necessary or indicated but can aid in the diagnostic evaluation, especially if there is a concern for infection as the etiology of the elevated residual volume.

Urinary catheterization after voiding can provide both a post-void residual and a urine specimen. It is particularly useful when a urine specimen is needed and not otherwise obtainable, as well as in cases of obvious urinary retention.

Urinary catheterization should be performed sterilely to prevent infection and to obtain an uncontaminated urine specimen.

Procedures

Measurement of the post-void residual volume (PVR) immediately after voiding is crucial for an accurate result, with delays of as little as 10 minutes from bladder emptying to PVR determination potentially causing clinically significant overestimation of the volume.[1]

Measurement of the PVR determines the quantity of urine remaining in the bladder shortly after a voluntary void; this measurement can be obtained using a portable dedicated bladder scanner, a formal bladder ultrasound examination, or by directly measuring the urine volume via urinary catheterization.

Urinary catheterization is the gold standard for measuring the PVR but is invasive and has several other disadvantages compared to ultrasound.[2]

Portable Dedicated Bladder Ultrasound Device

A portable dedicated bladder ultrasound device, commonly known as a bladder scanner, uses ultrasound to measure the three-dimensional volume of urine in the bladder. It is a simple, noninvasive approach to measuring the PVR and is usually the preferred approach when available. In addition, the technique is simple to learn and takes only a few minutes to perform.

The device is easily portable on a movable stand, and a single instrument can serve an entire office or department. However, the device must be calibrated periodically, and the initial financial outlay may be significant. Nevertheless, while moderately expensive, the device has proven cost-effective over time and facilitates patient care in primary care facilities and specialist offices.

The technique of PVR measurement using a bladder scanner is straightforward. With the patient supine, ultrasound gel is placed on the suprapubic area. The probe is placed on the gel and directed toward the bladder. A simple button is depressed, which initiates the examination of the bladder volume. The result is displayed on a screen for the operator to see. The process can be repeated to optimally align the bladder in the center of the display. The largest bladder volume is recorded.[3]

Different bladder scanner machines may have slightly different procedures, but the basics of the technique are similar across devices.

Bladder scanning is unsuitable for patients with severe abdominal scarring, prolapse of the uterus, or if currently pregnant.[4] Abdominal ascites may cause a falsely elevated measurement.[5]

Formal Bladder Ultrasound

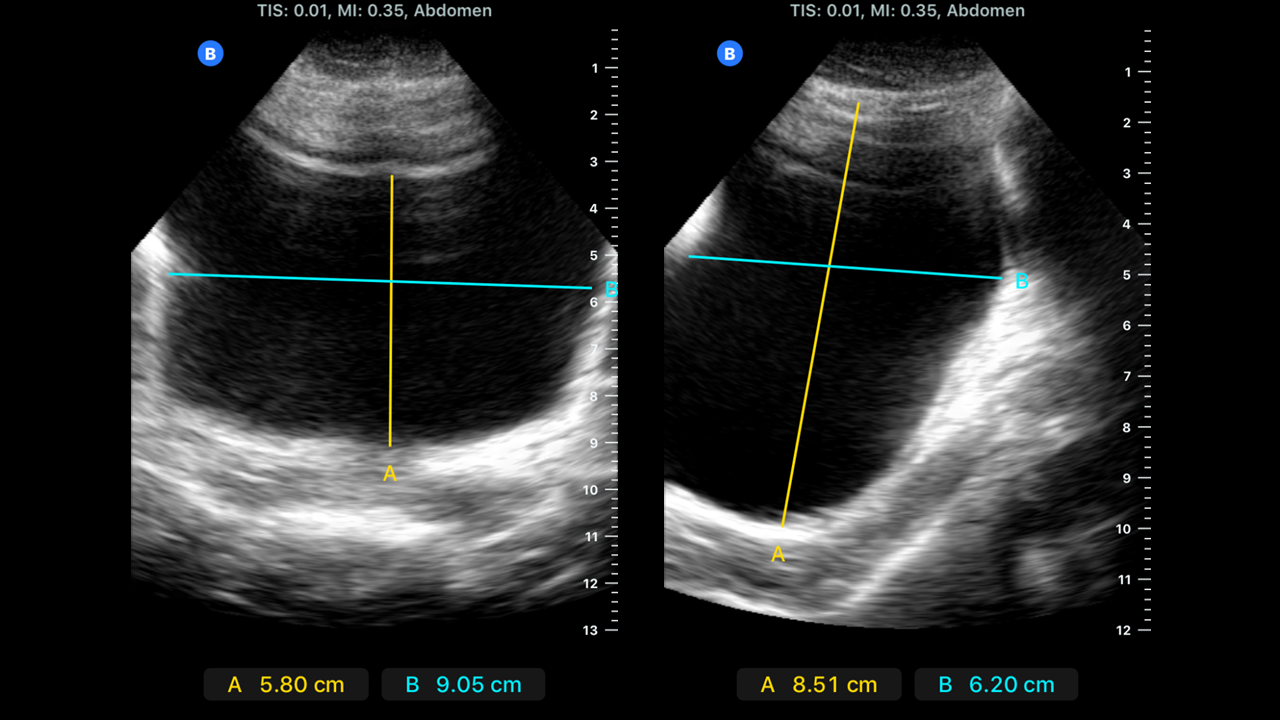

Conventional ultrasound is used to visualize the bladder directly, using either a transabdominal or transvaginal approach. The PVR is measured using the ultrasound machine's internal volume calculations or the mathematical equation below. Transvaginal ultrasound appears especially accurate for measuring low bladder volumes.[6]

For transabdominal bladder volume evaluation, the probe is placed over the suprapubic area while the patient is prone. Bladder images are recorded in both the sagittal and transverse planes. The greatest transverse (width), anteroposterior (depth), and superior-inferior (height) distances are recorded.[7]

For transvaginal bladder volume evaluation, an intracavitary transvaginal probe with frequencies between 7 to 9 MHz is used. Ensure the probe is clean, has a probe cover, and has gel placed onto the end of the probe. The patient should be supine with the legs in stirrups or a pad under the pelvis. The probe is inserted into the vagina, and bladder identification is in the sagittal plane. Measurements are from the longest anteroposterior dimension and the craniocaudal dimension. The probe is then rotated 90 degrees to measure the width or axial dimension.[8]

Most ultrasound machines have a function to automatically calculate volumes from the measurements used with the ultrasound calipers. The volumes can be calculated using the prolate ellipsoid formula if this function is unavailable. There are multiple mathematical methods to calculate volume, and the prolate ellipsoid formula below is one accepted method.[9][10]

- Volume = length x width x height x 0.52

The prolate ellipsoid formula has more than one acceptable correction factor. The bladder is measured at its maximal transverse (width), longitudinal (length), and anterior-posterior (height) diameters. This method is recommended as the standard calculation because it is fast and easy.[10]

Data on the accuracy of transabdominal ultrasound for determining the PVR is mixed. Although most studies demonstrate high accuracy using transabdominal point-of-care ultrasound or bladder scanners with automated measurement of bladder volume, other recent studies have questioned the accuracy of these methods.[3][11][12][13][14] There is some evidence that dedicated bladder scanners are more accurate than two-dimensional ultrasound imaging.[7]

For most practical purposes, an absolutely accurate measurement is not necessary for clinical decision-making, and a rough estimate is generally sufficient.

Urethral Catheterization

Urethral catheterization directly measures the PVR and is considered the gold standard of measurement. Varying the size and type of catheter used may result in variable results.[5]

While accurate, the technique has some significant disadvantages. First, it takes time and supplies. Second, it is an invasive technique that requires a trained professional to perform. Third, it is often uncomfortable for the patient and risks a urinary tract infection or possible injury to the urethra. Fourth, unexpected difficulty in placing the catheter may be encountered, causing bleeding or other complications. Finally, catheterization may not be possible in uncooperative individuals, babies, or children. However, it may be the optimal method when urinary retention is suspected or when noninvasive ultrasound equipment is unavailable or cannot be reliably used, as in patients with ascites or during the later stages of pregnancy.

While male and female anatomy each requires a different technique for inserting a urethral catheter, the overall procedure and sterile technique are similar. The steps in the technique are:

- Perform hand hygiene and place the patient in an accessible position; a female patient should be placed in the frog-leg position while males can remain supine.

- Sterile drapes should cover the genitals with the urethral meatus exposed, and sterile gloves should be worn.

- The non-dominant hand should hold the penis at a 90-degree angle toward the ceiling, and for females, the labia should be separated and held to expose the urethral meatus.

- The urethral meatus and glans penis for males or perineum for females should undergo prepping with an antiseptic solution using a sterile technique.

- Injection of 20 mL of a local anesthetic gel, such as lidocaine, into the urethra can help diminish patient discomfort during the procedure.[15]

- Insert a well-lubricated catheter (usually 14 or 16 French in size) into the urethral meatus with the dominant, sterile-gloved hand. For male patients, pulling the penis downwards towards the feet while advancing the catheter will tend to straighten the natural anterior curve of the bulbous urethra and facilitate passage into the bladder.

- Observe for a spontaneous return of urine to confirm catheter tip placement in the bladder.

- To obtain a urine sample or PVR, allow the bladder to drain completely into a graduated container, measure the volume, then remove the catheter.

If permanent drainage is desired or the need appears likely, use a Foley catheter and inflate the balloon with sterile water after satisfactory placement.[16] Ensure the balloon portion of the Foley is entirely inside the bladder before inflation. This usually means a full insertion of the catheter up to the hub in male patients before balloon inflation.

Special techniques and procedures exist for difficult or complicated urethral catheterizations.[17]

Urethral catheterization has known complications. Common traumatic complications include urethral trauma, the creation of a false urethral passage, stricture formation, and inadvertent balloon inflation in the urethra. The precursor of catheter-associated urinary tract infection is bacteria, which develops at an average rate of 3% to 10% per day of catheterization. The commonly studied incidence of infection relates to indwelling catheterization and not in-and-out catheterization, which would be used to identify a PVR or to obtain a sterile urine sample.[18][19]

Comparison of Methods

While no statistically significant difference in PVR results was found when measured using the bladder scanner or urinary catheterization, the average time to perform the bladder scan was 45 seconds. In contrast, the average urinary catheterization time was 293 seconds.[4]

Portable bladder scanning for PVR measurement is convenient, noninvasive, accurate, cost-effective, and carries no risk of urethral trauma or urinary tract infection.[20] It is particularly beneficial in various populations, including individuals with neurologic disease, children, babies, uncooperative patients, and the elderly, as well as other situations where catheterization would be difficult or traumatic.[20] Of note, some bladder scan machines include modifications to allow for the identification of abdominal aortic aneurysms. This makes them very cost-effective even for small primary care offices, not to mention finding potentially life-threatening aortic aneurysms that may otherwise have been missed.

Indications

A PVR is a valuable diagnostic tool for evaluating patients with various urological symptoms such as urgency, frequency, incomplete emptying, weak urinary stream, suprapubic pain or pressure, and bladder overactivity, incontinence, hesitancy, or stranguria. It can also be used when there is a concern for an underlying neurological disease or injury, bladder dysfunction, mechanical voiding obstruction, infection, or possible urinary retention.

The PVR is often best used in conjunction with a 24-hour voiding diary and an AUA Symptom score. Together, these non-invasive tools can provide the clinician with a reasonably clear understanding of urinary symptoms, bladder function, and emptying. Formal urodynamic testing can provide additional information, but this is costly, time-consuming, and often unnecessary with the optimal use of these non-invasive diagnostic tools.

Symptoms of urinary retention and PVR can be indirect. Common symptoms of acute urinary retention are lower abdominal pain and inability to pass urine; in young children or elderly patients with dementia, who can provide only a limited history, agitation may be the only sign of bladder overdistension.[21]

Determination of the PVR can identify those patients with incontinence who have overflow due to urinary retention. It can also track the progress and treatment effectiveness of therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia and other urinary disorders. Additionally, patients with cauda equina syndrome may present with low back pain, saddle anesthesia, bilateral sciatica, motor weakness of the lower extremities, paraplegia, or incontinence; determination of the PVR may be of use.[22] Young children may have urinary retention due to a refusal to urinate because of the dysuria caused by a urinary tract infection or other causes.

Interfering Factors

Limitations of Testing and Interfering Factors

When evaluating PVR volumes with ultrasonography, there is a false positive rate of 9% for urinary retention. This may be due to many factors, including pelvic masses such as ovarian cysts or uterine leiomyoma with cystic degeneration, ascites, scarring, device miscalibration, improper measuring technique, etc.

No standard perfect calculation for measuring bladder volume exists; different measurement modalities and devices may produce different bladder volumes.

It is critical to do the PVR measurement shortly after a voluntary void. Less than 10 minutes is optimal, but logistical problems often delay measurements for 20 minutes or longer. It is optimal if the patient indicates they need to urinate rather than being forced to void on command to take a measurement.[2][7][10][11][36]

Complications

Urinary catheterization is the gold standard to measure PVR but has significant limitations such as patient discomfort, low compliance, invasiveness, and risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) or injury.[2] One study of females in the post-operative period found the overall prevalence of UTI after catheterization was 2.3%. Still, the risk of UTI rose the longer the catheter was in place.[37]

In cases of urinary obstruction relieved by catheterization, post-obstructive diuresis (typically in cases of over 1,500 mL of retained urine) can cause hypovolemia and electrolyte abnormalities that may require admission for management.[35]

Patient Safety and Education

A PVR is a diagnostic tool to evaluate bladder function and detect underlying pathology. Bladder scanning and real-time transabdominal ultrasound are non-invasive and have no risk of ionizing radiation. Urethral catheterization carries some risks, including hematuria, urethral injury, discomfort, and infection but may be preferred in certain situations, such as obvious urinary retention.

Clinical Significance

Although there is no definitive consensus definition of an elevated PVR, there is no question that it can help identify and diagnose urinary retention and verify good bladder emptying. This helps determine the proper management of various bladder disorders and prevents further discomfort, disability, or even death. It is often best used in conjunction with a 24-hour voiding diary to help clarify various voiding dysfunctions and differentiate polyuria, overactive bladder, and overflow incontinence.

The appropriate and optimal use of post-void residual determinations is the early and correct diagnosis of urinary retention and other bladder disorders. Since this is often done non-invasively with dedicated ultrasonic scanners, it provides valuable evidence of bladder emptying ability and can be used to track therapy. It has proven useful in almost every type of urinary disorder. It is one of a handful of evidence-based, non-invasive diagnostic tools available to the clinician to treat various urinary symptoms that could be caused by many, sometimes contradictory, disorders.

Neurological Injury

Cauda equina syndrome is a serious condition that, if not managed expeditiously, leaves many patients with long-term neurological deficits. Urinary retention is considered a late sign predictive of paralysis, insensate bladder and bowel, and loss of sexual function.[38] One researcher found patients diagnosed with cauda equina with the sole findings of urinary retention and absent ankle reflexes with no other obvious neurological abnormalities.[25]

Long-standing neurogenic bladder can lead to loss of bladder compliance and refractory urinary incontinence, pyelonephritis, and possible renal function deterioration over time.[39] Non-neurologic causes of a large post-void residual can cause bladder muscle damage.

Infection

Conflicting data exist, but one study of stroke patients found a higher rate of UTIs developed in patients with a PVR over 100 ml.[40]

Obstruction

One researcher found that 9.5% of admitted patients to a geriatric unit with acute kidney injury had a pre-existing renal disease caused by obstructive uropathy.[41] Bladder outlet obstruction, namely benign prostatic hyperplasia, leads to profound changes and permanent damage to bladder structure and function, which may be irreversible.[42]