Continuing Education Activity

Nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis describes a group of diseases causing fibrosis to the lung parenchyma due to a known cause. This a serious condition that can result in respiratory failure and death. To avoid high morbidity and mortality, early diagnosis, and treatment are necessary. This activity illustrates the evaluation, and treatment of nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (nonidiopathic).

- Describe the presenting history and physical examination findings of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (nonidiopathic).

- Summarize the treatment and management options available for interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (nonidiopathic).

- Identify interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (non-IPF) describes a group of interstitial lung diseases (ILD) that cause inflammation and fibrosis of the lung interstitium leading to impaired gas exchange due to a known cause. Depending on the specific disorder, it can also affect the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli, and pleura. Most of these diseases are characterized by their clinical, radiographic, pathologic, and physiologic findings. The classic features often include progressive shortness of breath and cough, chest imaging abnormalities, and inflammatory and fibrotic changes on histology. A restrictive pattern with a decreased diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is often seen in pulmonary function testing (PFT).[1]

Etiology

There are over 200 known causes of non-IPF. The etiology for the most common causes are often categorized, as shown below.[2]

Occupational and environmental exposures:

- Pneumoconiosis due to inorganic substances and associated occupations

- Asbestos: Plumbers, shipyard and construction workers

- Beryllium: Aerospace workers and those involved in mining

- Carbon dust: Coal miners

- Silica: Silica mining and sandblasting

- Chromium: Metal and chemical manufacturing

- Organic substances causing hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Thermophilic fungi

- Avian droppings

- Bacterial species (i.e., B. subtilis, B. cereus)

Drug-induced lung toxicity

- Numerous drugs can cause interstitial pulmonary fibrosis.

- Common drugs include amiodarone, antineoplastic agents, beta-blockers, methotrexate, nitrofurantoin, statins, and radiation therapy.

Connective tissue diseases (CTD):

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Systemic sclerosis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Antisynthetase syndrome

- Polymyositis/dermatomyositis

- Mixed connective tissue disease

Systemic Illnesses:

- Sarcoidosis

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Lymphangiomyomatosis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody disease

- Chronic aspiration

- Alveolar proteinosis

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of non-IPF varies based on the underlying cause of the disease. However, pulmonary fibrosis of all types is slightly more common in men than women and often occurs in the fifth or sixth decades of life in both the United States and worldwide. The overall incidence of ILD of all types is 31.5 per 100,000 in men and 26.1 per 100,000 in women. The estimated prevalence ranges from 25 to 74 per 100,000 population.[1][3]

Pathophysiology

Although there are numerous known causes of non-IPF, the pathogenesis is similar between most diseases. The process involves phases of injury, inflammation, and repair. There is recurrent and direct epithelial/endothelial injury to the distal air spaces due to various causes (e.g., drug toxicity, environmental exposure, autoimmune reactions). Destruction of the alveolar-capillary basement membrane leads to platelet activation and fibrin-rich clot formation. Macrophages release proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, resulting in chemotaxis of neutrophils. The release of cytokines, reactive oxygen species, proteases, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) amplifies the inflammatory process. TGF-β released by macrophages and damaged tissue promotes fibroblast proliferation resulting in myofibroblast formation and secretion of fibrous proteins and ground substance, which form the extracellular matrix (ECM). Chronic inflammation from repetitive injury over time leads to continued thickening and fibrosis of the lung parenchyma. This process ultimately results in irreversible fibrosis and impaired gas exchange.[4][5][6]

Histopathology

If the diagnosis is unclear from a patient’s history and non-invasive testing, a lung biopsy is an option. The histological features and distribution of fibrosis vary between types of non-IPF. However, fibrosis may be described as scarring or thickening of the interstitial tissue. In addition to fibrosis, the findings suggestive of a few subtypes of non-IPF are shown below:

Pneumoconiosis

- Peribronchiolar thickening and granulomas

- Asbestosis[7]

- Asbestos body – iron coated asbestos fibers

- Berylliosis (chronic beryllium disease)[8]

- Noncaseating granulomas and/or mononuclear infiltrates

- Found in samples of bronchial walls and lung interstitium

- Indistinguishable from sarcoid granulomas

- Coal mine dust lung disease[9]

- Collections of carbon laden macrophages (coal macules)

- Coal nodules consisting of macules and fibrosis

- Silicosis[10]

- Small fibrotic nodules present in the upper lobes

- Silica crystals may be seen under polarized light microscopy

- In acute silicosis, alveoli may be filled with lipoproteinaceous material similar to alveolar proteinosis

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis[11]

- Diffuse interstitial inflammation with lymphocytic infiltrates

- Poorly formed nonnecrotizing granulomas and/or multinucleated giant cells with cholesterol clefts

- Peribronchiolar fibrosis extending to the periphery of the lobules (bridging fibrosis)

- Peribronchiolar metaplasia may be present in some cases

Sarcoidosis[12][13]

- Noncaseating epithelioid granulomas with multinucleated giant cells

- Typically found in the bronchovascular bundles, septa, and pleura

- Asteroid body – stellate inclusions within giant cells

- Schaumann body – laminated calcium and protein inclusions found within giant cells

History and Physical

It is vital to obtain a thorough history to identify the specific cause of non-IPF. Patients often present late in the fifth or sixth decades of life. The presentation is similar in most cases, with nonspecific symptoms of progressive dyspnea and cough. Some patients will present with wheezing, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis. Symptoms can range from several weeks to years and are often associated with long-term exposure to a specific substance or with autoimmune diseases. In addition to a personal or family history of autoimmune conditions, patients should be questioned about their medication and smoking history, radiation exposure, and occupational exposures to help determine the etiology. The etiologies discussed earlier include long-term inhalation of organic and inorganic substances, drug-induced toxicity, connective tissue diseases, and systemic illnesses. Patients may also present with extra-pulmonary manifestations, which may help narrow the diagnosis (e.g., scleroderma and Raynaud phenomenon in systemic sclerosis).

Physical findings may be normal and can vary between diseases. The following are findings that may be present on a physical exam.[14][15]

General

- Tachypnea and central cyanosis if hypoxia is present

- Fever may be present in connective tissue diseases or sarcoidosis

Head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat

- Sinusitis as seen in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome)

- Ocular manifestations including uveitis and retinal vasculitis may be associated with sarcoidosis

Lungs/thorax

- Fine end-expiratory crackles (velcro rales)

- Wheezing may be auscultated when there is airway involvement (i.e., Churg-Strauss syndrome or hypersensitivity pneumonitis)

Musculoskeletal

- Digital clubbing is a common and a nonspecific finding

- Patients with connective tissue diseases may have proximal muscle weakness seen in polymyositis, Raynaud phenomenon in systemic sclerosis, and other joint abnormalities

- Proximal muscle weakness, arthralgias, and Raynaud phenomenon may also be present in antisynthetase syndrome

Neurological

- Patients with sarcoidosis may present with cranial and/or peripheral neuropathies

- Mononeuritis multiplex in Churg-Strauss syndrome often present with asymmetric neuropathy

Skin

- Skin finding in patients with non-IPF are mostly related to connective tissue or systemic diseases

- Cutaneous vasculitis is seen in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Scleroderma may present with cutaneous thickening and facial telangiectasias

- Cutaneous thickening with Raynaud phenomenon is more suggestive of systemic sclerosis

- A heliotrope rash is suggestive of dermatomyositis

- Erythema nodosum may be seen in cutaneous sarcoidosis

- Rheumatoid arthritis may also have palpable subcutaneous nodules

Evaluation

Patients with suspected non-IPF should undergo laboratory and radiographic testing. In some cases, it may be necessary to perform a biopsy. Testing is tailored to the patient’s history and physical findings.

Initial laboratory testing should include a complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, serum urea, creatinine, and liver function tests. If the history and exam raise suspicion for an autoimmune process (e.g., arthritis, fever, fatigue, weight loss), serological testing may be indicated. Serologic testing often includes rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and extractable nuclear antigens (ENA). Further testing for anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant may be done if the ANA is elevated.

Other laboratory tests may include creatine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, tuberculin testing, and calcium levels. In patients with sarcoidosis, serum angiotensin-converting enzyme may be elevated. However, the test has low sensitivity and poor specificity and is not routinely used in the diagnostic workup. IgE levels and an antibody panel specific to a variety of known antigens may be measured when suspecting hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

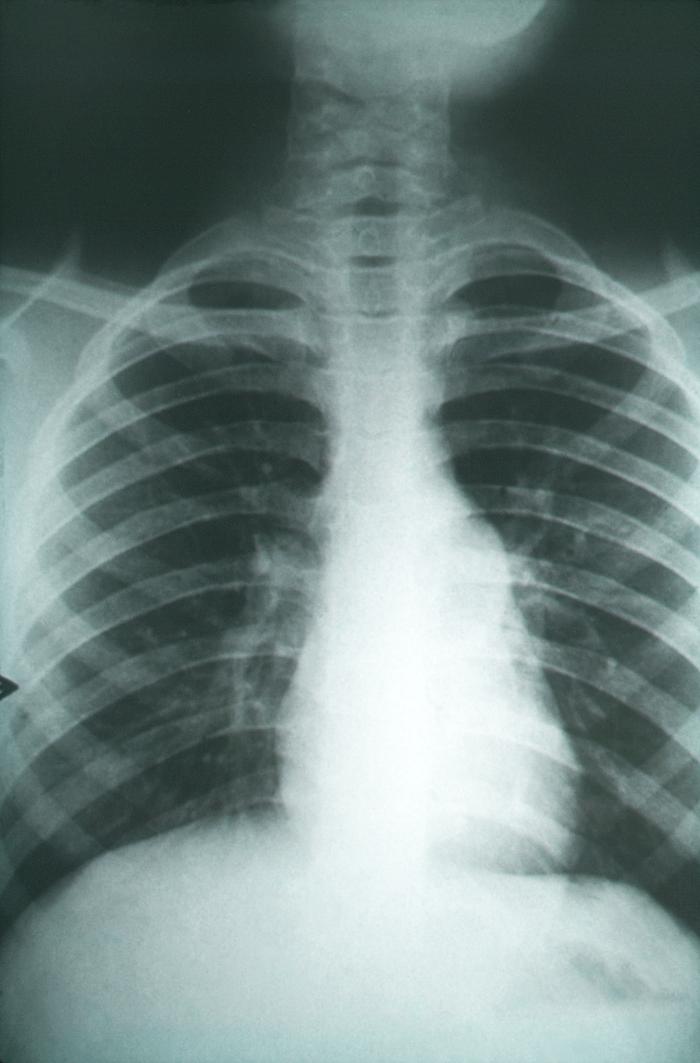

Imaging studies are key in evaluating and diagnosing non-IPF. It may be normal in the earlier stages of the disease. Abnormal findings may include low lung volumes, reticular and nodular opacities, and hilar lymph node prominence. The findings and patterns of distribution seen on chest x-ray may help narrow the etiology of non-IPF (e.g., mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy in sarcoidosis).

High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) has an important role in confirming ILD. The specificity of HRCT is dependent on the etiology of the disease. Patterns on HRCT, along with the clinical history, can often make the diagnosis and assist in staging. Common findings may include reticular opacities, centrilobular or perilymphatic nodules, ground-glass appearance, consolidation, and honeycombing. Honeycombing is a nonspecific late finding and appears as small cystic airspaces within areas of fibrosis. It develops over months to years and is associated with advanced disease.

In cases where the diagnosis remains unclear, further testing may include bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), and surgical lung biopsy. BAL may be useful if there is suspicion of malignancy or infection. Cell patterns on BAL samples may also help identify the etiology of non-IPF and exclude other causes. TBLB may be diagnostic in certain conditions as sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, malignancy, infections, alveolar proteinosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Surgical lung biopsies can be done via video-assisted thoracoscopy or as an open biopsy. Surgical biopsies provide a larger specimen without artifacts compared to TBLB. TBLB and surgical lung biopsies are often not required and are used to increase diagnostic confidence in cases where additional information will influence management.

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) should be obtained in all patients. PFTs are essential in the evaluation and diagnosis of non-IPF and are often used to assess disease severity and monitor disease progression. A complete PFT should include spirometry, body plethysmography, DLCO along with resting and ambulatory pulse oximetry. Patients with non-IPF typically have a restrictive pattern and a decrease in DLCO. The frequency of testing varies; however, it’s most often completed annually.[1][14][15][16]

Treatment / Management

Generally, the management of chronic disease primarily involves supportive measures including smoking cessation, influenza vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation, and instructing patients to avoid injurious agents (e.g., avoiding amiodarone in drug-induced fibrosis). Supplemental oxygen therapy may be necessary for patients with hypoxemia with a partial pressure of oxygen less than 55 mmHg or oxygen saturation of less than or equal to 88%. Further treatments vary based on the specific diagnosis. Corticosteroids may be used in certain conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis). A lung transplant may be considered as an option in severe or progressive disease. Patients should be evaluated early to be placed on the transplant waiting list.[1]

Acute exacerbations often occur and present as acute respiratory failure. In addition to supplemental oxygen, management typically involves intravenous corticosteroids (first-line). Intravenous (IV) cyclophosphamide may be used as a second-line treatment in patients with rapid progression of the disease or as first-line in those with ILD due to vasculitis.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

- Infection

- Pulmonary embolism

- Heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis/pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Pulmonary edema

- Pneumocystis pneumonia

Prognosis

Prognosis and mortality rates are highly variable based on etiology, the severity of the disease, rate of progression, pulmonary function testing, including DLCO, availability of medical therapy, and the presence of other comorbidities. Mortality rates can be as high as 100% during an acute exacerbation of non-IPF due to specific etiologies (i.e., connective tissue diseases, hypersensitivity pneumonitis). Mortality rates in all types of non-IPF increase with acute respiratory failure.[1]

Complications

There are numerous complications that can occur depending on the specific etiology, particularly in those with systemic illnesses. The following is a list of a few well-known complications in those with nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis:

- Acute and/or chronic respiratory failure

- Irreversible pulmonary fibrosis

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension in those with systemic sclerosis

- Cor pulmonale

- Thromboembolic disease

- Malignancy

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

Consultations

- Pulmonologist

- Interstitial lung disease clinic for complicated cases

- Transplant surgeon if indicated

- Rheumatologist for those with non-IPF due to a rheumatologic disease

Deterrence and Patient Education

- Smoking cessation

- Avoidance of exposure to harmful organic and inorganic substances

- Seek medical treatment for connective tissue diseases and other systemic illnesses

Pearls and Other Issues

Nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis is a progressive disease causing impaired gas exchange due to numerous causes. Early diagnosis is essential, and evaluation should consist of a careful history and physical exam along with the appropriate tests and consultations. Patients should be provided access to an interprofessional team of experts and pulmonary rehabilitation for adequate treatment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis requires an interprofessional team approach to optimize care and outcomes for the patient. This requires adequate communication between consultants, primary care physicians, nursing staff, and rehabilitation specialists. A study done at Brigham and Women’s Hospital found that the involvement of a pulmonologist, rheumatologist, radiologist, and pathologist in an interprofessional interstitial lung disease clinic had changed the diagnosis in 54% of the patients. Therapy changed in 80% of patients with interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease and 27% of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.[Level 3] Advanced directives and goals of care should also be established early in the course of the disease. Patients should be extensively educated on their disease and the importance of modifying factors, as discussed above (i.e., smoking cessation, avoidance of harmful substances, and treatment of systemic illnesses).[17]