Introduction

The quadratus lumborum (QL) muscle resides in the deep and posterior, lateral, and inferior areas of the spine, involving the iliac crest, the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae, and the 12th rib. The muscular organization is complex, and it is difficult to identify precisely the actions that occur through the contraction of fibers. It is an integral part of the thoracolumbar fascia. There is still no certainty that an abnormality of QL is the primary source of back pain. The QL could potentially act as a crossroad of the forces exerted by the neighboring muscles, influencing the vectors of the different tensions produced. Thanks to its strategic position and the entropic scheme of its fibers, QL is a significant means of access for anesthesia during surgery on the back, lower limbs, or abdominal area. The article reviews the latest anatomical and clinical information on the quadratus lumborum.

Structure and Function

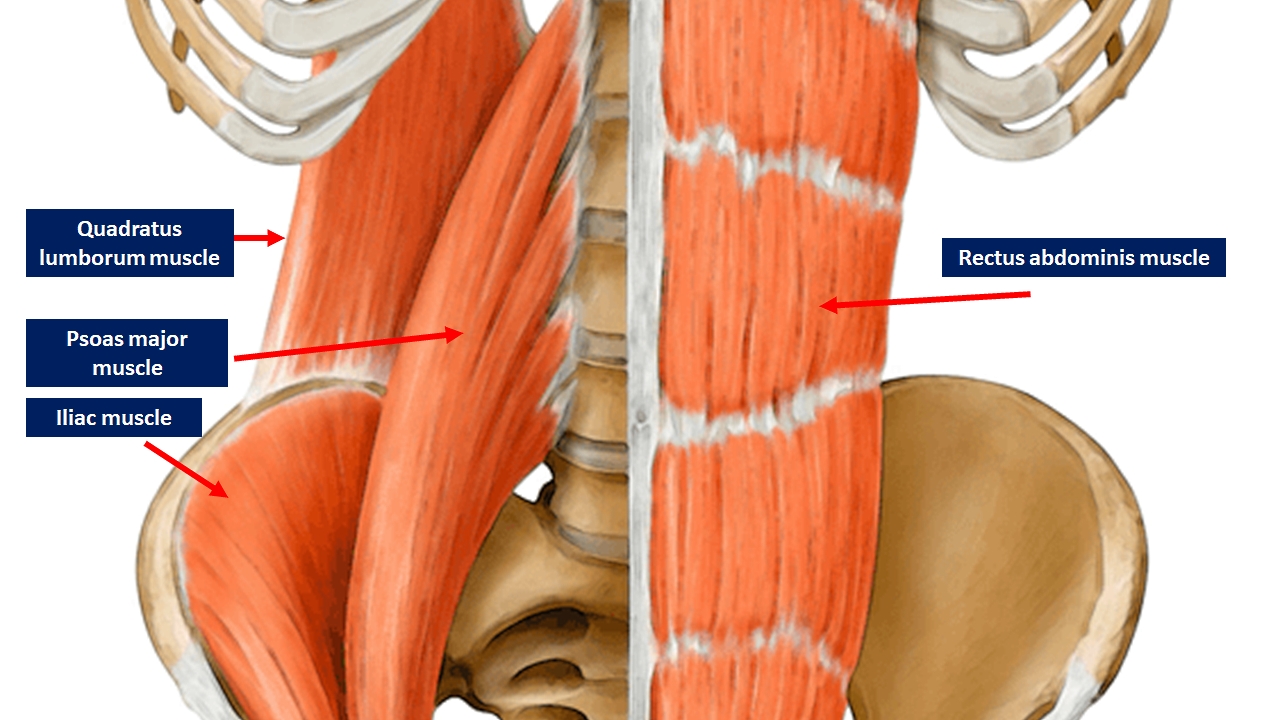

The quadratus lumborum (QL) muscle is an integral part of the thoracolumbar fascia, a myofascial system that covers the posterior area of the human body, involving part of the lower and upper limbs. The QL muscle is flattened and has a quadrangular shape; along with the multifidus and erector spinae muscles, the QL helps to create an antagonist force compared to the muscles of the abdomen.

The quadratus lumborum muscle involves the 12th rib (internal surface) and the transverse processes of the lumbar bodies of L1-L4, while it comes from the iliac crest (inner lip) and the iliolumbar ligament.[1]

Anatomy

QL comprises three layers with muscle fibers that have different vectors.

- The superficial layer is a thin layer comprising iliocostal muscle fibers (from the iliac crest to the ribs) and iliothoracic (from the iliac crest to the lateral area of the vertebral body of T12) which fibers have a tendinous or even muscular termination.

- The intermediate layer comprises lumbocostal muscle fibers (from the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae to the 12th rib). They are muscle fibers that vary significantly in size, direction, and thickness.

- The posterior layer consists of lateral iliocostal fibers and medially from iliolumbar fibers (from the iliac crest, connecting to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae). The iliocostal muscle bundles may involve the thoracolumbar fascia, inserting themselves with their tendon endings. This layer is thicker in the caudal area and more tapered in the rostral portion.[2]

Given the arrangement of the highly variable QL muscle fibers, it is not possible to recognize a precise pattern of orientation.

Generally, the QL muscle is located medially to the aponeurosis of the transverse abdominal muscle.

Function

The anatomy texts describe the quadratus lumborum muscle as an extensor of the lumbar spine, a stabilizer of the lumbar area, capable of tilting laterally and capable of acting as an inspiratory accessory muscle. A cadaver study has raised many doubts about the action of QL. During the extension, the QL exerts a force of 10 N, compared to 100 N and 150 N of the erector spinae muscles and the multifidus.[2] It seems unlikely that it can extend the lumbar area on a sagittal plane with such a small force (10 N).

The QL is positioned laterally, but despite its position during a lateral tilt of the trunk, it exerts only a force of 10 N. QL participates with less than 10% of the force required for a coronal inclination.

The force exerted by the musculature of the erector spinae and multifidus in the lumbar vertebrae is about 1800 N and 2800 N, respectively. QL exercises only 200 N, and as such, it does not appear to play a significant role as a lumbar stabilizer muscle.

Regarding its accessory inspiratory muscle function, due to the mobility of the last rib, QL will not be capable of transmitting the contractile force towards the diaphragm.[2]

It seems likely that QL could act as a crossroad of the forces exerted by the neighboring muscles, influencing the vectors of the different tensions produced, thanks to its strategic position and the entropic scheme of its fibers.[1]

The lateral arcuate ligament of the diaphragm rests on the QL, and, probably, this relationship could help the respiratory muscle: QL could act as a pivot.

Embryology

The embryonic mesoderm leaflet, already visible from the second week of gestation, gives rise to the skeletal musculature.

The mesoderm differs in four areas in the medial-lateral direction:

- The chordomesoderm, which makes up the notochord.

- The paraxial mesoderm is organized in two slings, lateral to the notochord and longitudinal course, which, thanks to the formation of transverse grooves, are fragmented into metameric small masses.

- The intermediate mesoderm, adjacent to the somites, in the cervical, thoracic, and caudal regions.

- The lateral mesoderm furthest from the notochord and delaminated in two parallel sheets.

During embryonic development, the median cellular cord forms the notochord, which represents the first axile apparatus of the embryo, with a short life but responsible for the phenomena of induction towards the surrounding areas. Starting from the cephalic end of the embryo, the mesoderm on the sides of the notochord (paraxial mesoderm), due to the formation of transverse grooves, is fragmented into two series of cylindrical thickenings with a spiral organization called somitomeres.

The segmentation in somitomeres begins in the most cranial region of the mesoderm with a more marked metamer in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal regions.

The first seven pairs of somitomeres have a slightly accentuated segmentation and form the striated muscles of the face, of the jaw, and of the neck, all subsequent forms of segmental units called somites.

About 42 to 44 somites form, of which the first corresponds to the eighth somitomere.

The first four pairs of somites form in the occipital region, where they contribute to the formation of occipital and facial bones as well as of the eye and tongue muscles.

Eight pairs of cervical somites follow: the first contributes to the formation of the occipital, the other seven form the cervical vertebrae, the muscles, and the dermis associated with them.

In succession, we find 12 pairs of thoracic somites (which form the vertebrae, the musculature, and the bones of the rib cage, and enter the upper limb formation), 5 of lumbar somites (which form the lumbar vertebrae, the muscles, and the abdominal dermis), 5 of sacral somites (which form the sacrum with the associated muscles and dermis), and 3 to 5 of coccygeal somites (which form the coccyx).[3][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

QL gets its vascular supply via the lumbar arteries and a lumbar branch of the iliolumbar artery. The lumbar arteries are four on each side, born from the posterior face of the aorta at the level of the first four lumbar vertebrae. They run posteriorly behind the sympathetic chain and under the arches tendon of the iliopsoas muscle to finally meet the QL muscle. The first three arteries pass posteriorly to the quadratus lumborum, while the fourth passes anteriorly.[5]

- The iliolumbar artery is the first tributary of the internal iliac artery (or hypogastric artery). It rises behind the psoas muscle and the iliacus muscle (iliac fossa), where the individual branches feed the iliac muscle. From it depart the branches that flow into the psoas muscle, the QL, the transverse muscle of the abdomen, and a branch of the spinal canal between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum.[6]

- The lumbar veins of each side are joined by longitudinal anastomotic vessels, which coalesce to form a small vertical trunk called the ascending lumbar vein. This vessel communicates, at the inferior end, with the iliolumbar vein and sometimes with the common iliac vein; at the superior aspect, it gives rise to the azygos vein on the right and the left hemizygous vein, thus constituting an essential anastomotic pathway between the inferior vena cava system and the superior vena cava system.[5]

- The lumbar lymph nodes of the abdominal cavity, which drain the lymph from the QL, are associated with the inferior vena cava and the abdominal aorta.[7]

Nerves

QL receives innervation via the twelfth thoracic intercostal nerve, the iliohypogastric nerve, and the ilioinguinal nerve.[1]

Muscles

In a small percentage of the population (approximately 2.9%), the subcostal muscle runs in front and contacts the QL, in particular with its terminal portion. The subcostal muscle is activated electrically during expiration, leading to the supposition that the QL could influence forced expiration, but further study is warranted.[8]

Quadratus lumborum is a continuation of transverse abdominal muscle. The latter is part of the anterior fascial system of the body (from the deep anterior fascia of the neck, the endothoracic fascia, to the transversalis fascia up to the pubis). The transversalis fascia penetrates the abdominal musculature. We can assume that an abnormal tension of these muscles (globular abdomen) can negatively influence the resting tension of the QL, altering the distribution of the lumbar area loads.

Physiologic Variants

There are no reports of hyperplasia or agenesis of the QL muscle in the literature.

Surgical Considerations

Dr. Blanco Rafael was the first to use quadratus lumborum anesthesia in surgery in 2007. Both anterior or posterior access are valid approaches, either lateral or intramuscular, with the help of ultrasound-guided assistance.[9] Anesthesia administered in this manner covers dermatomes from T4 to L2; the anesthetic passes through the paravertebral spaces and then distributes via the blood and lymphatic vessels and nerves. The use of this method can be useful not only before surgery (abdominal surgery, colostomy, cesarean section, laparoscopy, pyeloplasty, gastrotomy, and more) but also in the postoperative period to relieve pain.

Hip Fracture Surgery

Patients presenting with hip fractures are commonly clinically complicated secondary to advanced age and an increased number of medical comorbidities. Thus, innovative anesthetic techniques that ideally balance the risk of anesthesia without compromising pain control are a major goal of the overall treatment and management of these patients. The quadratus lumborum block (QLB) has demonstrated clinical efficacy and, when used in isolation or combined with other analgesic modalities, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in perioperative pain control for this group of patients.[10][11]

Clinical Significance

There is no consensus in the literature whether an alteration of the tone of QL may be the primary cause of back pain.[12] The size of the quadratus lumborum is smaller in the dominant's side leg compared to the opposite side. In the case of low-back pain, the QL does not vary much in its size compared to people without pain.[13][14]

It is likely that since the twelfth thoracic, ilioinguinal, and iliohypogastric nerves pass and give branches to the QL, the possibility exists that in cases of inflammation of the nervous tissue due to a limited excursion (entrapment), these tissues can produce a syndrome that mimics low-back pain.

Trigger points can involve the QL. This condition could also mimic a painful syndrome of the lumbar area.[15]

Another cause of low back pain, combined with the anatomical presence of QL, is the emergence of a heterotopic ossification or myositis ossificans.[16] The latter may result from direct trauma and inadequate healing, or in the absence of trauma, the etiopathogenesis may not always be clear.

One must consider that it is difficult for a single muscle to cause pain, except with direct trauma. All the muscles interconnect as a function of the fascial system, and in a contractile area with altered function, it will lead to functional difficulty in all the surrounding muscular regions.

Other Issues

One of the best possible approaches to working non-surgical QL is a fascial osteopathic treatment. The latter is a gentle procedure, respecting the pain of the patient able to improve the sensations of pain.[17]

A recent study has shown that the use of dry needling on the gluteus maximus muscle and quadratus lumborum is able to relieve pain with improved performance in athletes suffering from patellofemoral pain syndrome. [18]