Introduction

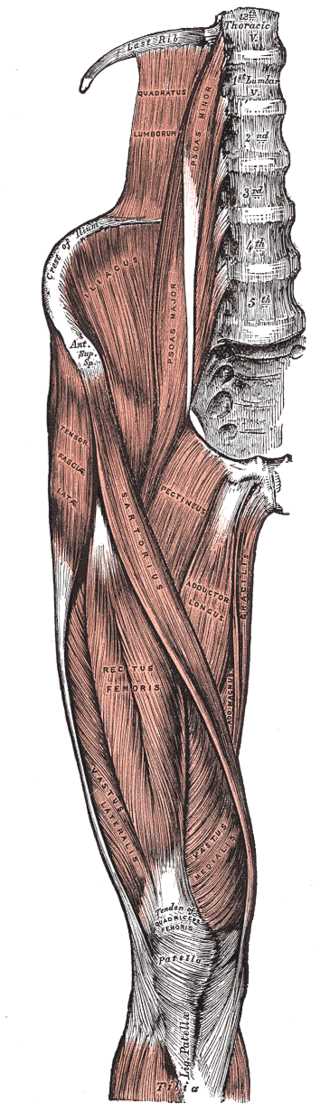

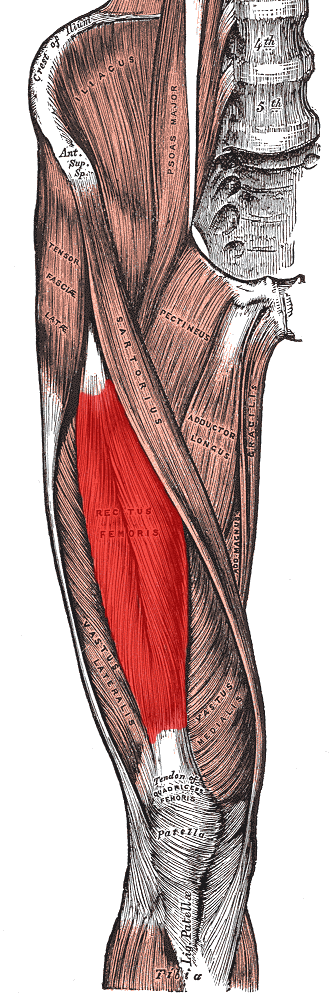

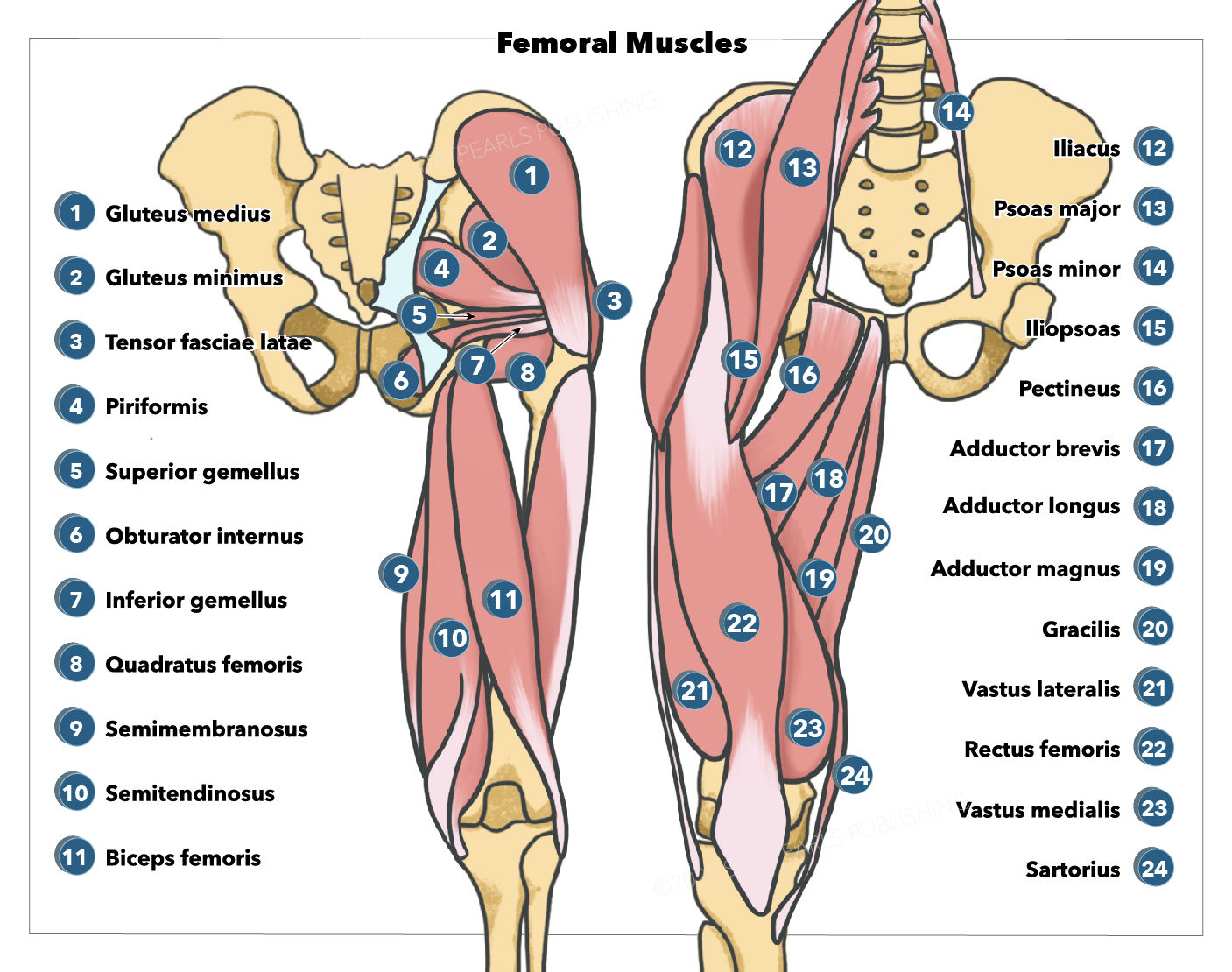

The rectus femoris is a long, fleshy muscle located in the anterior compartment of the thigh. The rectus femoris is fusiform in shape with superficial fibers that are bipenniform and deep fibers that run straight (rectus) to the deep aponeurosis.[1] The rectus femoris is the most superficial of the quadriceps muscles, alongside the vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis. These four muscles conjoin to attach to the patella as the quadriceps tendon. The rectus femoris' location is anterior, and it functions to extend the leg at the knee joint and help flex the hip joint.[1][2]

The rectus femoris has two heads of origin: the direct (straight) head and the indirect (reflected) head. The direct head arises from the anterior aspect of the inferior iliac spine (AIIS; a common site of avulsion), while the indirect head originates from the acetabular ridge. The two heads merge to become the conjoined tendon below their origin.[3]