[1]

DuPont HL, Levine MM, Hornick RB, Formal SB. Inoculum size in shigellosis and implications for expected mode of transmission. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1989 Jun:159(6):1126-8

[PubMed PMID: 2656880]

[2]

Stoll BJ, Glass RI, Huq MI, Khan MU, Banu H, Holt J. Epidemiologic and clinical features of patients infected with Shigella who attended a diarrheal disease hospital in Bangladesh. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1982 Aug:146(2):177-83

[PubMed PMID: 7108270]

[3]

Barrett-Connor E, Connor JD. Extraintestinal manifestations of shigellosis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1970 Mar:53(3):234-45

[PubMed PMID: 5435635]

[4]

Echeverria P, Sethabutr O, Pitarangsi C. Microbiology and diagnosis of infections with Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1991 Mar-Apr:13 Suppl 4():S220-5

[PubMed PMID: 2047641]

[5]

Khan WA, Griffiths JK, Bennish ML. Gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal manifestations of childhood shigellosis in a region where all four species of Shigella are endemic. PloS one. 2013:8(5):e64097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064097. Epub 2013 May 17

[PubMed PMID: 23691156]

[6]

McCrickard LS, Crim SM, Kim S, Bowen A. Disparities in severe shigellosis among adults - Foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 2002-2014. BMC public health. 2018 Feb 7:18(1):221. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5115-4. Epub 2018 Feb 7

[PubMed PMID: 29415691]

[7]

Kotloff KL, Riddle MS, Platts-Mills JA, Pavlinac P, Zaidi AKM. Shigellosis. Lancet (London, England). 2018 Feb 24:391(10122):801-812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33296-8. Epub 2017 Dec 16

[PubMed PMID: 29254859]

[8]

Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, Kabir F, Nkeze J, Okoi C, Operario DJ, Uddin J, Ahmed S, Alonso PL, Antonio M, Becker SM, Blackwelder WC, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Fields B, Gratz J, Haque R, Hossain A, Hossain MJ, Jarju S, Qamar F, Iqbal NT, Kwambana B, Mandomando I, McMurry TL, Ochieng C, Ochieng JB, Ochieng M, Onyango C, Panchalingam S, Kalam A, Aziz F, Qureshi S, Ramamurthy T, Roberts JH, Saha D, Sow SO, Stroup SE, Sur D, Tamboura B, Taniuchi M, Tennant SM, Toema D, Wu Y, Zaidi A, Nataro JP, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Houpt ER. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Sep 24:388(10051):1291-301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31529-X. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27673470]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[9]

MOSLEY WH, ADAMS B, LYMAN ED. Epidemiologic and sociologic features of a large urban outbreak of shigellosis. JAMA. 1962 Dec 29:182():1307-11

[PubMed PMID: 13936184]

[10]

Painter JA, Hoekstra RM, Ayers T, Tauxe RV, Braden CR, Angulo FJ, Griffin PM. Attribution of foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths to food commodities by using outbreak data, United States, 1998-2008. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013 Mar:19(3):407-15. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.111866. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23622497]

[11]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Shigella flexneri serotype 3 infections among men who have sex with men--Chicago, Illinois, 2003-2004. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2005 Aug 26:54(33):820-2

[PubMed PMID: 16121121]

[12]

Hines JZ, Pinsent T, Rees K, Vines J, Bowen A, Hurd J, Leman RF, Hedberg K. Notes from the Field: Shigellosis Outbreak Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Homeless Persons - Oregon, 2015-2016. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016 Aug 12:65(31):812-3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6531a5. Epub 2016 Aug 12

[PubMed PMID: 27513523]

[14]

Bowen A, Eikmeier D, Talley P, Siston A, Smith S, Hurd J, Smith K, Leano F, Bicknese A, Norton JC, Campbell D, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the Field: Outbreaks of Shigella sonnei Infection with Decreased Susceptibility to Azithromycin Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - Chicago and Metropolitan Minneapolis-St. Paul, 2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015 Jun 5:64(21):597-8

[PubMed PMID: 26042652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[15]

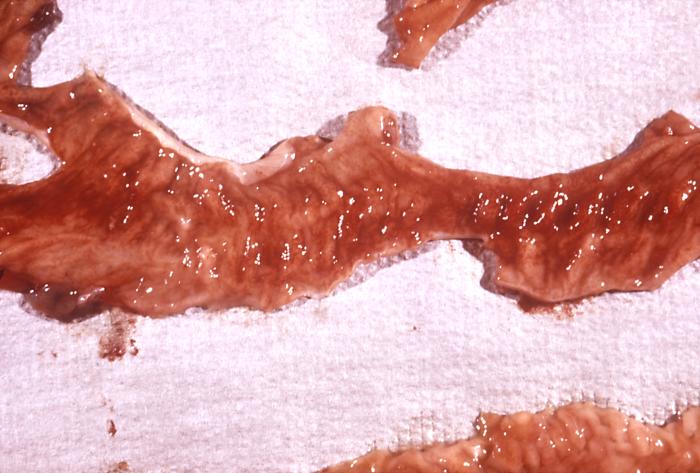

Mathan MM, Mathan VI. Morphology of rectal mucosa of patients with shigellosis. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1991 Mar-Apr:13 Suppl 4():S314-8

[PubMed PMID: 2047656]

[16]

Zychlinsky A, Thirumalai K, Arondel J, Cantey JR, Aliprantis AO, Sansonetti PJ. In vivo apoptosis in Shigella flexneri infections. Infection and immunity. 1996 Dec:64(12):5357-65

[PubMed PMID: 8945588]

[17]

Mathan VI, Mathan MM. Intestinal manifestations of invasive diarrheas and their diagnosis. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1991 Mar-Apr:13 Suppl 4():S311-3

[PubMed PMID: 2047655]

[18]

Sur D, Ramamurthy T, Deen J, Bhattacharya SK. Shigellosis : challenges & management issues. The Indian journal of medical research. 2004 Nov:120(5):454-62

[PubMed PMID: 15591629]

[19]

Erqou S, Teferra E, Mulu A, Kassu A. A case of shigellosis with intractable septic shock and convulsions. Japanese journal of infectious diseases. 2007 Sep:60(5):314-6

[PubMed PMID: 17881877]

[20]

Ferrera PC, Jeanjaquet MS, Mayer DM. Shigella-induced encephalopathy in an adult. The American journal of emergency medicine. 1996 Mar:14(2):173-5

[PubMed PMID: 8924141]

[21]

Fried D, Maytal J, Hanukoglu A. The differential leukocyte count in shigellosis. Infection. 1982 Jan:10(1):13-4

[PubMed PMID: 7068229]

[22]

Halpern Z, Averbuch M, Dan M, Giladi M, Levo Y. The differential leukocyte count in adults with acute gastroenteritis. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 1992:24(2):205-7

[PubMed PMID: 1641598]

[23]

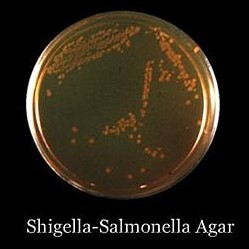

Rahaman MM, Huq I, Dey CR. Superiority of MacConkey's agar over salmonella-shigella agar for isolation of Shigella dysenteriae type 1. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1975 Jun:131(6):700-3

[PubMed PMID: 1094073]

[24]

Bennish ML. Potentially lethal complications of shigellosis. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1991 Mar-Apr:13 Suppl 4():S319-24

[PubMed PMID: 2047657]

[25]

Keusch GT, Bennish ML. Shigellosis: recent progress, persisting problems and research issues. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1989 Oct:8(10):713-9

[PubMed PMID: 2682504]

[26]

Martin T, Habbick BF, Nyssen J. Shigellosis with bacteremia: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Pediatric infectious disease. 1983 Jan-Feb:2(1):21-6

[PubMed PMID: 6340078]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[27]

Struelens MJ, Patte D, Kabir I, Salam A, Nath SK, Butler T. Shigella septicemia: prevalence, presentation, risk factors, and outcome. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1985 Oct:152(4):784-90

[PubMed PMID: 4045231]

[28]

Davies NE, Karstaedt AS. Shigella bacteraemia over a decade in Soweto, South Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008 Dec:102(12):1269-73. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.037. Epub 2008 Jun 11

[PubMed PMID: 18550134]

[29]

Bennish ML, Salam MA, Wahed MA. Enteric protein loss during shigellosis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1993 Jan:88(1):53-7

[PubMed PMID: 8420274]

[30]

DuPont HL, Hornick RB. Adverse effect of lomotil therapy in shigellosis. JAMA. 1973 Dec 24:226(13):1525-8

[PubMed PMID: 4587313]

[31]

Heiman KE, Karlsson M, Grass J, Howie B, Kirkcaldy RD, Mahon B, Brooks JT, Bowen A, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the field: Shigella with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin among men who have sex with men - United States, 2002-2013. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2014 Feb 14:63(6):132-3

[PubMed PMID: 24522098]

[32]

Khan WA, Seas C, Dhar U, Salam MA, Bennish ML. Treatment of shigellosis: V. Comparison of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine. 1997 May 1:126(9):697-703

[PubMed PMID: 9139555]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[33]

Rahman M, Shoma S, Rashid H, El Arifeen S, Baqui AH, Siddique AK, Nair GB, Sack DA. Increasing spectrum in antimicrobial resistance of Shigella isolates in Bangladesh: resistance to azithromycin and ceftriaxone and decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Journal of health, population, and nutrition. 2007 Jun:25(2):158-67

[PubMed PMID: 17985817]

[34]

Salam MA, Dhar U, Khan WA, Bennish ML. Randomised comparison of ciprofloxacin suspension and pivmecillinam for childhood shigellosis. Lancet (London, England). 1998 Aug 15:352(9127):522-7

[PubMed PMID: 9716056]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[35]

Traa BS, Walker CL, Munos M, Black RE. Antibiotics for the treatment of dysentery in children. International journal of epidemiology. 2010 Apr:39 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i70-4. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq024. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20348130]

[36]

Azad MA, Islam M, Butler T. Colonic perforation in Shigella dysenteriae 1 infection. Pediatric infectious disease. 1986 Jan-Feb:5(1):103-4

[PubMed PMID: 3511451]

[37]

Bennish ML, Azad AK, Yousefzadeh D. Intestinal obstruction during shigellosis: incidence, clinical features, risk factors, and outcome. Gastroenterology. 1991 Sep:101(3):626-34

[PubMed PMID: 1860627]

[39]

Butler T, Islam MR, Bardhan PK. The leukemoid reaction in shigellosis. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1984 Feb:138(2):162-5

[PubMed PMID: 6695872]

[40]

Ashkenazi S, Dinari G, Zevulunov A, Nitzan M. Convulsions in childhood shigellosis. Clinical and laboratory features in 153 children. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1987 Feb:141(2):208-10

[PubMed PMID: 3544808]

[41]

Khan WA, Dhar U, Salam MA, Griffiths JK, Rand W, Bennish ML. Central nervous system manifestations of childhood shigellosis: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Pediatrics. 1999 Feb:103(2):E18

[PubMed PMID: 9925864]

[42]

Porter CK, Choi D, Riddle MS. Pathogen-specific risk of reactive arthritis from bacterial causes of foodborne illness. The Journal of rheumatology. 2013 May:40(5):712-4. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121254. Epub 2013 Apr 1

[PubMed PMID: 23547220]

[43]

Murphy TV, Nelson JD. Shigella vaginitis: report of 38 patients and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1979 Apr:63(4):511-6

[PubMed PMID: 375177]

[44]

Tobias JD, Starke JR, Tosi MF. Shigella keratitis: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1987 Jan:6(1):79-81

[PubMed PMID: 3547292]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[45]

Rubenstein JS, Noah ZL, Zales VR, Shulman ST. Acute myocarditis associated with Shigella sonnei gastroenteritis. The Journal of pediatrics. 1993 Jan:122(1):82-4

[PubMed PMID: 7678291]

[46]

Taylor DN, Bodhidatta L, Brown JE, Echeverria P, Kunanusont C, Naigowit P, Hanchalay S, Chatkaeomorakot A, Lindberg AA. Introduction and spread of multi-resistant Shigella dysenteriae I in Thailand. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1989 Jan:40(1):77-85

[PubMed PMID: 2644859]

[47]

Huan PT, Taylor R, Lindberg AA, Verma NK. Immunogenicity of the Shigella flexneri serotype Y (SFL 124) vaccine strain expressing cloned glucosyl transferase gene of converting bacteriophage SfX. Microbiology and immunology. 1995:39(7):467-72

[PubMed PMID: 8569531]

[48]

Keren DF, Kern SE, Bauer DH, Scott PJ, Porter P. Direct demonstration in intestinal secretions of an IgA memory response to orally administered Shigella flexneri antigens. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 1982 Jan:128(1):475-9

[PubMed PMID: 7033378]

[49]

Rasolofo-Razanamparany V, Cassel-Beraud AM, Roux J, Sansonetti PJ, Phalipon A. Predominance of serotype-specific mucosal antibody response in Shigella flexneri-infected humans living in an area of endemicity. Infection and immunity. 2001 Sep:69(9):5230-4

[PubMed PMID: 11500390]

[50]

Wilmer A, Romney MG, Gustafson R, Sandhu J, Chu T, Ng C, Hoang L, Champagne S, Hull MW. Shigella flexneri serotype 1 infections in men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. HIV medicine. 2015 Mar:16(3):168-75. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12191. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25656740]

[51]

Das JK, Tripathi A, Ali A, Hassan A, Dojosoeandy C, Bhutta ZA. Vaccines for the prevention of diarrhea due to cholera, shigella, ETEC and rotavirus. BMC public health. 2013:13 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S11. Epub 2013 Sep 17

[PubMed PMID: 24564510]

[52]

Baker KS, Dallman TJ, Field N, Childs T, Mitchell H, Day M, Weill FX, Lefèvre S, Tourdjman M, Hughes G, Jenkins C, Thomson N. Horizontal antimicrobial resistance transfer drives epidemics of multiple Shigella species. Nature communications. 2018 Apr 13:9(1):1462. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03949-8. Epub 2018 Apr 13

[PubMed PMID: 29654279]

[53]

Hines JZ, Jagger MA, Jeanne TL, West N, Winquist A, Robinson BF, Leman RF, Hedberg K. Heavy precipitation as a risk factor for shigellosis among homeless persons during an outbreak - Oregon, 2015-2016. The Journal of infection. 2018 Mar:76(3):280-285. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.11.010. Epub 2017 Dec 5

[PubMed PMID: 29217465]

[54]

Williamson D, Ingle D, Howden B. Extensively Drug-Resistant Shigellosis in Australia among Men Who Have Sex with Men. The New England journal of medicine. 2019 Dec 19:381(25):2477-2479. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910648. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31851807]

[55]

Ingle DJ, Easton M, Valcanis M, Seemann T, Kwong JC, Stephens N, Carter GP, Gonçalves da Silva A, Adamopoulos J, Baines SL, Holt KE, Chow EPF, Fairley CK, Chen MY, Kirk MD, Howden BP, Williamson DA. Co-circulation of Multidrug-resistant Shigella Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Australia. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2019 Oct 15:69(9):1535-1544. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz005. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30615105]

[56]

Liang M, Ding X, Wu Y, Sun Y. Temperature and risk of infectious diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2021 Dec:28(48):68144-68154. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15395-z. Epub 2021 Jul 15

[PubMed PMID: 34268683]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[57]

Shad AA, Shad WA. Shigella sonnei: virulence and antibiotic resistance. Archives of microbiology. 2021 Jan:203(1):45-58. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-02034-3. Epub 2020 Sep 14

[PubMed PMID: 32929595]

[58]

Arnold SLM. Target Product Profile and Development Path for Shigellosis Treatment with Antibacterials. ACS infectious diseases. 2021 May 14:7(5):948-958. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00889. Epub 2021 Mar 10

[PubMed PMID: 33689318]

[59]

Mani S, Wierzba T, Walker RI. Status of vaccine research and development for Shigella. Vaccine. 2016 Jun 3:34(26):2887-2894. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.075. Epub 2016 Mar 12

[PubMed PMID: 26979135]

[60]

Puzari M, Sharma M, Chetia P. Emergence of antibiotic resistant Shigella species: A matter of concern. Journal of infection and public health. 2018 Jul-Aug:11(4):451-454. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.025. Epub 2017 Oct 20

[PubMed PMID: 29066021]