Continuing Education Activity

The cerebellopontine angle (CPA) is an important landmark anatomically and clinically. The most common lesions at the CPA are vestibular schwannoma, meningioma, and epidermoid. Treatment options include observation, radiosurgery, and microsurgery. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of cerebellopontine angle tumors and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Summarize the etiology of cerebellopontine angle tumors.

- Explain the evaluation of cerebellopontine angle tumors.

- Outline the management of cerebellopontine angle tumors.

Introduction

Cerebellopontine angle (CPA) is a triangular space in the posterior cranial fossa that is bounded by the tentorium superiorly, brainstem posteromedially and petrous part of temporal bone posterolaterally. It is an important landmark anatomically and clinically as it is occupied by the CPA cistern, which houses the cranial nerve V, VI, VII, and VIII along with the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.[1]

The clinical significance of CPA stems from the variety of lesions that involve this region and present with a myriad of non-specific symptoms, the most common of which are sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and dizziness.[2] CPA tumors can be broadly classified into two types; those arising from structures located in the CPA, and those extending from adjacent regions into the CPA.

Etiology

CPA tumors are mostly benign, slow-growing tumors with low potential for malignancy (~1%).[3] The etiology of vestibular schwannoma remains unknown. However, there are two major types;

- Sporadic: These are unilateral tumors and most commonly present between the fourth and sixth decade of life.

- Those associated with neurofibromatosis (NF) type 2: The most common presentation is bilateral acoustic neuromas in younger patients with a positive family history. NF2 results from a mutation at the chromosome 22q12. This mutation leads to an increased risk of other intracranial tumors as well.[1]

Schwannomas are the primary lesion of cranial nerves involving trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, vagus, and sometimes even accessory cranial nerve.

Meningiomas arise from the proliferation of arachnoid meningothelial cells, most commonly from the dura of petrous temporal bone or internal auditory meatus.[3]

Epidermoid tumors arise from congenital misplacement of ectodermal cells during the closure of the neural tube.[1][3]

Arachnoid cysts are CSF filled cysts that arise from the splitting of embryonic arachnoid membranes.[3]

Epidemiology

Between 5 and 10% of all intracranial tumors are located in the cerebellopontine angle.[1] The most common tumors at the CPA are vestibular schwannoma, meningioma, and epidermoid tumors. Vestibular schwannoma accounts for 75 to 85% of all CPA tumors; meningiomas account up to 10 to 15%, whereas epidermoids make up 7 to 8% of all CPA tumors. Other less common tumors that roughly contribute 1% each include cranial nerve schwannomas (other than cranial nerve VIII), arachnoid cysts, lipoma, glomus jugulare, and metastatic lesions.[1][4] Also seen are the epidermoids, dermoids, and inter-axial intraventricular tumors like choroid plexus papilloma. Some of the extremely rare tumors in CPA are the hamartomas, respiratory epithelial cysts, teratomas, chondromas, chondrosarcoma, astrocytomas, medulloblastomas, ependymomas, brainstem gliomas, and salivary gland heterotopias.[5]

Even though the primary intracranial melanomas in the primary CPA region are sporadic but when present can express with severe symptoms of ataxia, hearing loss, and dysphagia.[6]

Histopathology

Vestibular schwannoma is composed of two distinct regions microscopically; Antoni A and Antoni B. Antoni A is made up of compact, well organized bipolar cells that may palisade (Verocay bodies). Antoni B, on the other hand, is composed of loosely organized myxoid tissue. The tumor has a strong S100 positivity.[7]

Meningiomas have a varied histological appearance and are classified into several types based on the predominant histological architecture. Common varieties include meningothelial (syncytial and epithelial cells with poorly defined borders and classic whorls), fibroblastic (firm tumor comprised of spindle cells and undefined cell borders), and transitional (both meningothelial and fibroblastic components). Other less common subtypes include angiomatous, psammomatous, metaplastic, microcystic, secretory and lymphocytic. WHO grading system divides meningiomas into three grades, i.e., grade I to grade III based on histological features, presence of anaplasia, and prognosis. The majority of meningiomas are benign, slow-growing (grade I).[8]

Epidermoid tumors are cystic lesions with squamous epithelium and keratin components. They begin from sequestrated epithelial cells of migrating optic and otic capsules. These are slow-developing tumors not associated with any other congenital abnormalities. They grow by the accumulation of keratin and cholesterol, which is produced by the desquamation of the epithelium that is lining the mass.

Arachnoid cysts have a delicate fibrous wall that is lined by meningothelial cells. They are cystic spaces containing cerebrospinal fluid or xanthochromic fluid. They are heterogeneous in their appearance.[5]

Lipomas are fatty tumors that cause bone erosions. But the nerves and blood vessels pass easily through the tumor without any signs of displacement.

History and Physical

The most common presenting symptoms of lesions involving the CPA include hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness, vertigo, headaches, and gait dysfunction. Hearing loss is mostly unilateral sensorineural and is due to the involvement of the cochlear nerve. Other cranial nerve deficits, brainstem compression symptoms, and hydrocephalus can also be seen with larger tumors compressing these structures.

Evaluation

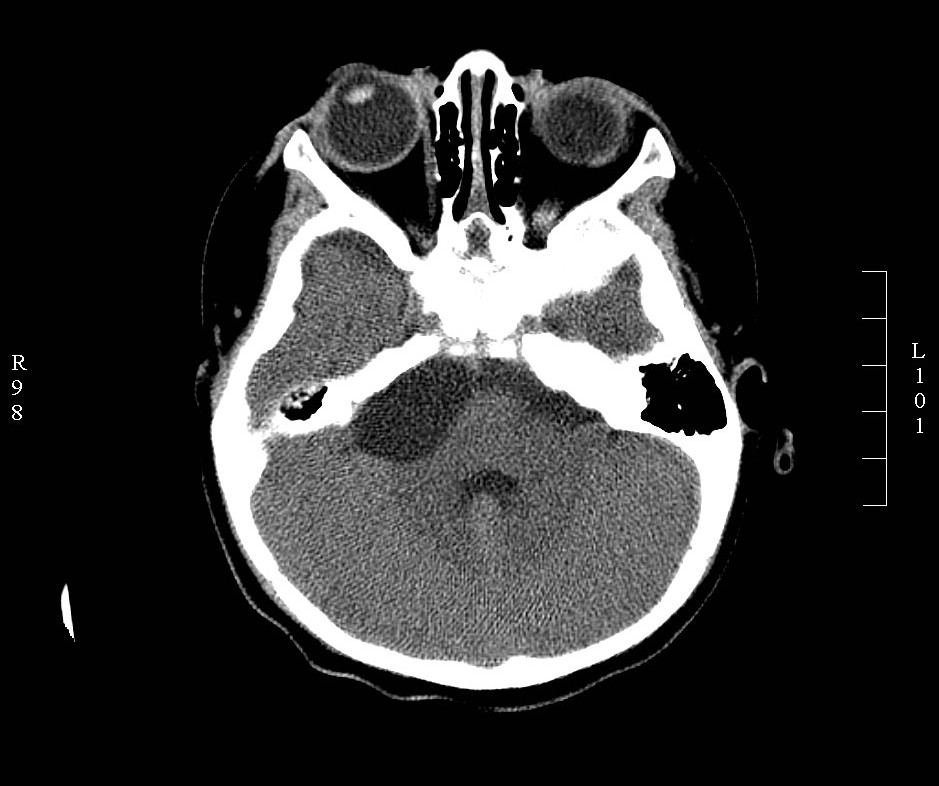

The diagnosis of CPA tumors is made based on history, physical examination, audiometric and radiological evaluation. Magnetic resonance image (MRI) is the gold standard for the diagnosis of CPA tumors. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) is useful for the assessment of bony involvement. Vestibular schwannoma appears isodense on CT, hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 MRI.[1][3] Meningiomas appear hyperdense on CT, hypointense on T1, and hyperintense on T2. Differentiating features of meningioma from vestibular schwannoma include a hyperdense appearance on non-contrast CT, lack of internal auditory canal erosion, broad dural attachment, cleft of CSF between the tumor and brain parenchyma and thickening of dura around the tumor (dural tail sign).[4] Meningiomas also present more commonly with headaches, while vestibular schwannoma presents with profound hearing loss. Epidermoids present with non-specific CPA signs and symptoms. Radiological appearance can be varied, with the most common being T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense (‘black lesion’).[1][3][4]

When trying to differentiate meningioma from vestibular schwannomas, more advanced MRI data information such as MR spectroscopy metabolite peaks and perfusion ratios are necessary. Also, better information on more specific features such as ice-cream-cone shape, adjacent hyperostosis, presence of calcification, a dural tail that might be extended into any skull base foramina should help final diagnosis.[9]

Treatment / Management

Treatment options for CPA tumors include observation, radiation therapy, or microsurgery. Observation is suitable for elderly/unstable patients and in tumors with little/no evidence of growth. The tumor is monitored with routine annual scans, and tumor growth necessitates aggressive treatment. Another disadvantage of this approach is that the cranial nerve function becomes difficult to preserve with delay in treatment.[2]

Radiation therapy provides adequate tumor control with low rates of recurrence.[2] However, worsening of hearing status and cranial neuropathies are also common side effects following radiosurgery.

It should be remembered that any surgical approach is quite a challenge in treating the CPA tumors as it involves complex regional anatomy, enormous vital structures present in the surgical field, and as it allows a very narrow surgical corridor to operate.[10] In the case of meningiomas, complete surgical excision of the tumor along with the hyperostotic bone and surrounding dura is the choice. But in vestibular schwannomas, the strategy has been changed from total radical excision to a more aggressive subtotal excision to preserve neurological functions.[5]

Microsurgery offers a definitive solution. The goal of microsurgery is complete tumor removal as well as hearing preservation. The different surgical approaches that can be used are translabrynthine, middle fossa, and retrosigmoid approach.[2] The choice of surgical procedure is made based on the size of the tumor, the extension of the tumor within the canal, the surgeon’s preference, and baseline hearing function.[2][11] The most commonly used approach is retrosigmoid (RS) or the sub-occipital approach. This approach allows hearing preservation while providing adequate exposure. Disadvantages of RS include CSF leak, headache, cerebellar retraction, and a higher risk of tumor recurrence because of limited ability to remove intracanalicular portion of the tumor.[2][12] However, a combined endoscopic/microscope approach can improve access to deep-seated lesions.[13]

The middle fossa approach is most useful to resect the intracanalicular extension of the tumor. Disadvantages of the MF approach include temporal lobe retraction, hematoma following rupture of the middle meningeal artery, and a higher risk of facial nerve injury. Translabrynthine approach can be used in patients without any serviceable hearing as the surgical morbidity of this procedure is low as compared to others.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CPA mass includes primary CPA tumors like vestibular schwannoma, meningioma, epidermoid, non-vestibular schwannoma, congenital, vascular, and metastatic lesions.[1][14][15] Tumors from adjacent regions may also extend to the CPA and include ependymoma, choroid plexus papilloma, brainstem glioma, or hemangioblastoma.[15][4] Other lesions, including vascular malformations, inflammatory/granulomatous tissue, and neuritis, can also present similarly.[15][3]

Prognosis

Cerebellopontine tumors are usually benign, slow-growing tumors. The treatment outcome depends on the size, location, and consistency of the tumor. Delayed treatment is associated with poor outcomes, and therefore, early detection and treatment are essential.[11] Post-operative imaging should be carefully reviewed to differentiate normal post-surgical changes from recurrence.[14]

Complications

The most common complications following radiosurgery are cranial neuropathy, hydrocephalus, and brainstem/cerebellar injury.[12] Complications following surgery include headache, hemorrhage, stroke, vascular injury, infection, cranial nerve injury, tumor recurrence, CSF leak, and death.[2][12] The conventional surgical complication involving cranial nerve dysfunctions is due to lesions in the facial, trigeminal, and vestibulocochlear nerves.[5] Approximately 10% of cases of trigeminal neuralgia have been attributed secondary to CPA tumors.[16]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Non-specific symptoms, e.g. headaches, hearing loss, dizziness, prompt the workup for the diagnosis of CPA tumors. Radiation therapy can be utilized for elderly patients or medically unstable patients. Although tumor growth is halted, tumor re-growth and radiation-induced tumors remain a concern.[2] Surgical treatment is curative, and every attempt to preserve cranial nerve function should be made.[11]

Pearls and Other Issues

Even though they are sporadic, the papillary thyroid carcinoma can metastases to the CPA.[17] It has also been reported that ductal carcinoma of breast can rarely cause metastases to CPA and can mimic vestibular schwannomas.[18]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CPA tumors should be evaluated using a multi-specialty team comprising neurotologist, neurosurgeon, oncologist, radiologist, and a radiation oncologist (Level 3).[2][11]

Team approach and intra-operative neuro-monitoring help to improve the outcomes and reduce the incidence of nerve injury (Level 3).[11][19]

The choice of surgical approach is influenced by the size of the tumor, its extent, and hearing status.[11]

Post-operative changes should be evaluated carefully to differentiate them from tumor recurrence.[12]