Introduction

The skin is divided anatomically into distinct patterns based on the specific distribution of sensory nerve fibers arising from a single spinal nerve. These patterns were mapped and discussed most prominently in 1933 by O. Foerster in a publication entitled “The Dermatomes in Man” in the journal Brain, which some consider the founding basis on which dermatomal theory rests.[1] After Foerster, J. Keegan and F. Garrett discussed the distribution of spinal nerves in 1948 in their publication "The Segmental Distribution of the Cutaneous Nerves in the Limbs of Man” in the journal The Anatomical Record.[2] Most recently, in 2008, M. Lee, R. McPhee, and M. Stringer published an article in Clinical Anatomy entitled “An Evidence-Based Approach to Human Dermatomes,” in which they contested some of the classic presentations of dermatome maps and put forth an evidence-based method for determining a more accurate map of human dermatomes.[3][4]

Structure and Function

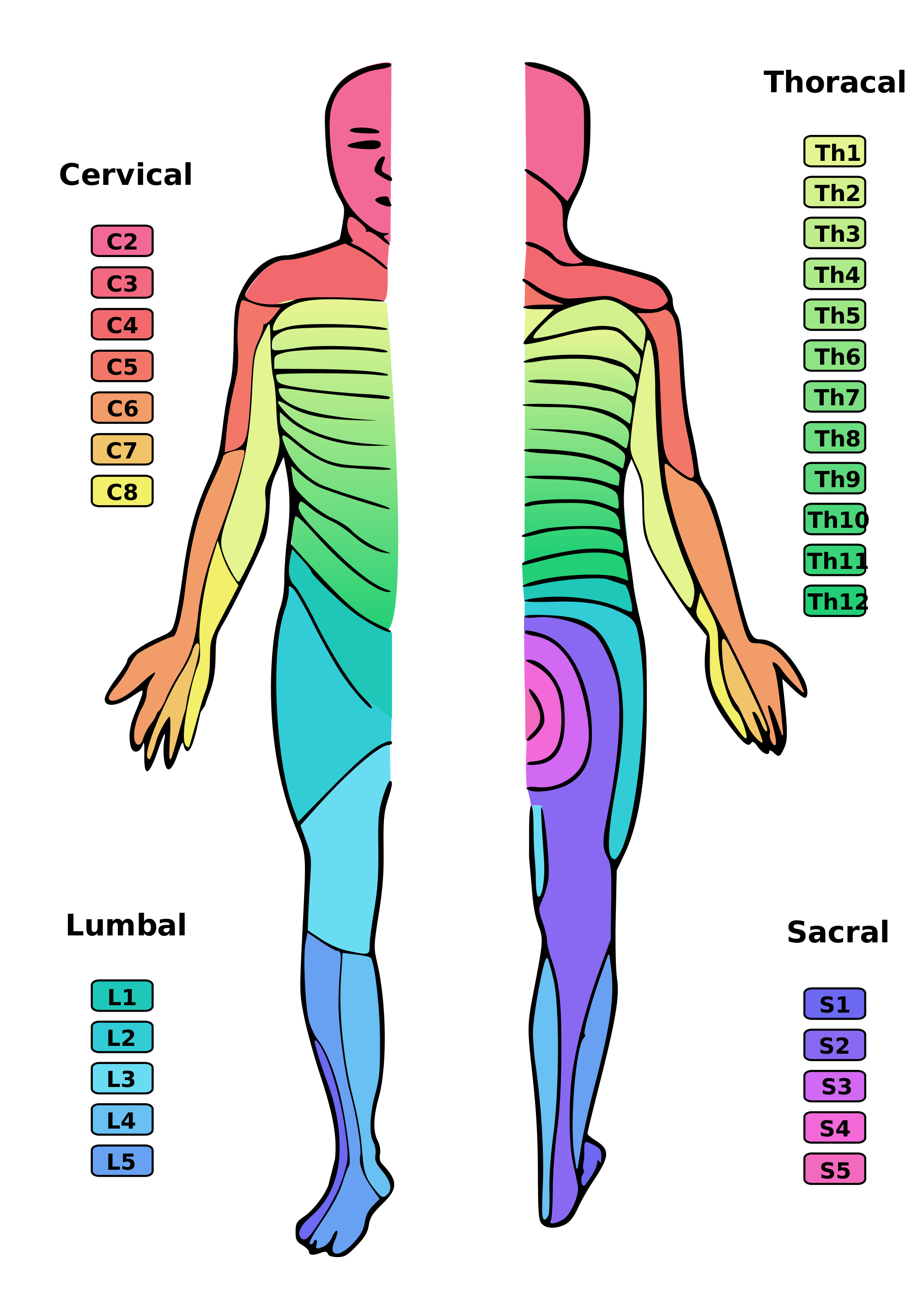

Spinal nerves form from the dorsal nerve roots and the ventral nerve roots which branch from the dorsal and ventral horn of the spinal cord, respectively. The spinal nerves exit through the intervertebral foramina or neuroforamina and travel along their respective dermatomal distributions from posterior to anterior, creating the specific, observable dermatomal patterns.[5]In total, there are 31 distinct spinal segments and thus 31 distinct spinal nerves bilaterally. These 31 spinal nerves are composed of 8 pairs of cervical nerves, 12 pairs of thoracic nerves, five pairs of lumbar nerves, five pairs of sacral nerves, and one pair of coccygeal nerve.[5]

The cervical nerves C1-C7 exit through the intervertebral foramina above their respective vertebrae. Cervical nerve C8 exits between the C7 vertebra and the T1 vertebra. The remaining spinal nerves all exit below their respective vertebrae.[5]

The dermatomes on the trunk are layered horizontally, one on top of the other. This horizontal pattern contrasts with the pattern on the extremities, where it is typically more longitudinal. This pattern is fairly standard although some variations can exist from person to person because spinal nerves overlap in the areas of the body they supply.

Embryology

During embryological development, spinal nerves develop from neural crest tissue allowing for the formation of dermatomal, myotomal, and scleratomal patterns. The spinal cord begins development during the third week of the embryonic period with the formation of the neural plate and the elevation of the neural folds. Early in the fourth week of development, the neural folds begin to fuse. Late in the fourth week, neuroblasts form and move into the intermediate zone of the early neural tube, and this process continues throughout embryological development. During the sixth week, spinal nerves begin to form and progressively travel from dorsal to ventral.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The spinal cord and the spinal nerves receive their vascular supply predominantly via the anterior spinal artery and two posterior spinal arteries. The anterior spinal artery supplies the bulk of the spinal cord, the anterior two-thirds, while the two posterior spinal arteries supply the dorsal columns. These spinal arteries branch off the vertebral arteries in the skull and proceed out of the skull and course inferiorly along the spinal cord.[7]

Nerves

Several anatomic landmarks help easily identify or estimate different dermatomal levels.

- C6 - Thumb

- C7 - Middle finger

- C8 - Little finger

- T1 - Anteromedial forearm and arm

- T2 - Medial forearm and arm to the axilla

- T4 - Nipple

- T6 - Xyphoid process

- T10 - Umbilicus

- L3 - Medial knee

- L4 - Anterior knee and medial malleolus

- L5 - Dorsal surface of the foot and first, second, and third toes

- S1 - Lateral malleolus

Clinical Significance

Neurological evaluation of dermatomes helps to assess radiculopathy or neurologic deficits as radicular patterns can suggest specific spinal nerve involvement. For example, sciatica, a common condition with a lifetime prevalence reported as high as 84%, will often present along the dermatome of the involved spinal nerve.[8] Sciatica-associated pain will commonly follow a path from the posterior hip down the back of the thigh to the knee involving the S1 or S2 dermatome. Neurological assessment of dermatomes helps to assess the level of spinal cord injury.[9]

Herpes zoster infections, colloquially known as chickenpox and shingles, are caused by varicella zoster virus or human herpesvirus 3 (HHV-3). In the primary varicella infection, the distribution is widespread and diffuse, progressing in a cephalocaudal manner with classic lesions often described as “dew drops on a rose petal.” With the resolution of the primary infection, the virus retreats into the dorsal root ganglia awaiting reactivation. Viral reactivation can frequently be due to a triggering event while in an immunocompromised state, but immunosuppression is not requisite for reactivation of the virus and presentation of the secondary disease.[10]

Once reactivated, the viral symptoms typically present in 3 different phases. The pre-eruptive, or prodromal, phase exhibits symptoms associated with sensory phenomena presenting along the affected dermatome. These sensory symptoms may present as pain, burning, itching, or paresthesias. After the pre-eruptive phase follows the eruptive phase during which the affected dermatome erupts in a grouped vesicular rash (herpetiform) on an erythematous base. The vesicular lesions will most commonly present along a truncal dermatome, with facial onvolvement the second most prevalent. The lesions progress through a pattern of vesicles, pustules, crusting, and resolution.[11]

Disseminated herpes zoster is significantly rare and almost exclusively associated with severely immunocompromised states (i.e., AIDS, malignancy, long-term immunosuppressive therapy use, etc.). Affected patients are also at risk of life-threatening conditions including encephalitis or pneumonitis.

Of particular concern for herpes zoster infections is the involvement of the cranial nerves, particularly the trigeminal nerves (CN V). Herpes zoster ophthalmicus presents similarly to herpes zoster infections affecting the trunk, beginning with the prodromal phase of burning or itching on the skin, and can sometimes be clinically confused with trigeminal neuralgia while still in the pre-eruptive stage. The concern with herpes zoster ophthalmicus is that with the eruptive phase, lesions distribute along the face, and if involving the optic nerve, the oculomotor nerve, or the trigeminal nerve, blindness can result. Hutchinson’s sign, herpetic lesions along the lateral nose tip, indicates the involvement of the nasociliary branch of the first trigeminal nerve and is ominous of potential ocular involvement.[12]

Upon resolution of the lesions, pain can remain and continue to affect patients along the affected dermatome as postherpetic neuralgia.[11]