Continuing Education Activity

Stridor is an abnormal, high-pitched respiratory sound produced by irregular airflow in a narrowed airway during the inspiration phase. Stridor can result from various congenital and acquired conditions. Diagnosis for this condition is aided by considering the patient's age and the onset of symptoms. In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, healthcare professionals may perform x-rays or bronchoscopy on patients to determine the etiology of stridor—a manifestation of an underlying pathology that requires a comprehensive patient history and physical examination. In young children and infants, even minor inflammation can lead to significant and rapid airway obstruction. Therefore, healthcare professionals must have a thorough understanding of the underlying causes of stridor and be highly skilled in evaluating and addressing compromised airways while comprehending the root causes of the condition. This topic delves into the pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and clinical management of stridor while also highlighting the integral role of the interprofessional healthcare team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify signs and symptoms of stridor in children and its potential underlying causes.

Apply knowledge of the underlying causes of stridor in children, enabling effective management and treatment decisions.

Implement timely diagnostic measures, such as x-rays or bronchoscopy, when diagnostic uncertainty regarding stridor exists.

Collaborate with a multidisciplinary team, including pulmonologists, radiologists, and respiratory therapists, to optimize the evaluation and management of stridor in children.

Introduction

Stridor is an abnormal, high-pitched respiratory sound produced by irregular airflow in a narrowed airway. This condition indicates significant upper airway obstruction and is usually most prominent during the inspiration phase. Identifying the underlying disease process is crucial in managing stridor symptoms. The medical history, age, and symptom acuity of a child aid in distinguishing the underlying cause of the condition.

Congenital malformations, life-threatening obstructions, or acute infections can cause stridor. In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, healthcare professionals may perform x-rays or bronchoscopy on patients to determine the etiology of stridor. In young children and infants, even minor inflammation can lead to significant and rapid airway obstruction.[1] The timing of stridor during the respiratory cycle provides valuable insights into the level of obstruction. The inspiratory stridor indicates a laryngeal obstruction, whereas the expiratory stridor suggests a tracheobronchial obstruction. Biphasic stridor is commonly associated with subglottic or glottic anomalies. This topic addresses both acquired and congenital causes of stridor and the evaluation and treatment of stridor in children.

Etiology

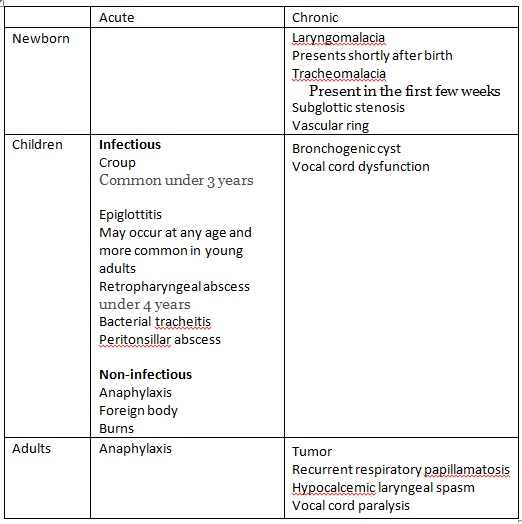

Stridor is a manifestation of an underlying pathology and may result from acute or chronic factors. Although the symptoms associated with acute causes of stridor typically emerge within minutes to hours, they can also develop over days. Patients with acute stridor are at risk of experiencing rapid progression of their symptoms. In contrast, chronic stridor is caused by a congenital or acquired abnormality, and it may persist for weeks. Although chronic stridor generally becomes apparent within the first few weeks of life, some cases may manifest later in childhood.

Laryngotracheitis, commonly known as croup, is the primary cause of stridor in infants and children, often attributed to the parainfluenza virus. Laryngomalacia, characterized by the collapse of supraglottic structures during inspiration, is the leading cause of extrathoracic airway obstruction in infants.[2] Additional bacterial infectious causes of stridor include Neisseria meningitidis, Pasteurella multocida, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S pyogenes, and other streptococci. Viral pathogens include influenza A and B, herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2. These pathogens can lead to epiglottitis, croup, peritonsillar abscesses, and retropharyngeal abscesses.

Acute Causes of Stridor

Acute causes of stridor encompass conditions such as croup, bacterial tracheitis, epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess, foreign body aspiration, peritonsillar abscess, airway burns, anaphylaxis, therapeutic hypothermia, and post-extubation complications.

Chronic Causes of Stridor

Chronic causes of stridor include conditions such as craniofacial anomalies like Pierre Robin or Apert syndromes, macroglossia-inducing disorders, laryngomalacia, laryngeal webs, laryngeal cysts, laryngeal clefts, subglottic stenosis, vocal cord paralysis, tracheal stenosis, tracheomalacia, vascular ring, bronchogenic cysts, infantile hemangiomas, tumors, respiratory papillomatosis, and hypocalcemic laryngeal spasm.

Stertor, which manifests as snoring during sleep, results from airway constriction in the nasal, nasopharyngeal, or oropharyngeal regions. Stertor can be distinguished from stridor due to its characteristic low-pitched sound.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of stridor varies based on the underlying cause. Stridor is a more frequent presentation among pediatric patients than in adults. Croup reaches its highest incidence between 6 and 36 months, leading to 350,000 to 400,000 croup-related emergency department visits annually. Croup affects 2% to 6% of infants and children annually, with a slightly higher prevalence among males than females, at a ratio of 1.4:1.

Foreign body aspiration accounts for more than 17,000 emergency department visits per year in the United States, with most cases occurring in children younger than 3.[3]

Pathophysiology

When trying to identify the cause of stridor, it is important to determine whether the location of the issue is from within the chest cavity (intrathoracic) or from outside of it (extrathoracic).

Extrathoracic

The supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic areas fall within the extrathoracic category. Rapid narrowing in the supraglottic areas can occur because of the absence of cartilage. In infants, the subglottic region is a critical area where even minimal airway narrowing can significantly elevate airway resistance. An obstruction in the extrathoracic region is responsible for causing inspiratory stridor. This occurs because, during inspiration, the intratracheal pressure falls below atmospheric pressure, resulting in airway collapse. Common causes of stridor in the extrathoracic region are laryngomalacia, croup, a retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, and craniofacial malformations.

Intrathoracic

The intrathoracic region encompasses the tracheal section located within the thoracic cavity and the mainstem bronchi. Congenital disorders are the common causes of airway narrowing in this area. An obstruction within the intrathoracic region results in an expiratory stridor. This occurs because, during expiration, elevated pleural pressure compresses the airway, leading to a reduction in airway size at the site of the intrathoracic obstruction.

Children who exhibit narrowing at the glottis level may experience inspiratory or biphasic stridor because this airway segment remains virtually unchanged during respiration. This can occur in cases involving foreign bodies and subglottic stenosis.

History and Physical

Patient History

The patient's medical history plays a pivotal role in guiding clinical decision-making. Factors such as age, acuity of symptoms, symptom severity, and any history of chronic stridor are instrumental in guiding the differential diagnosis.

Based on the age or acuity of symptoms, possible diagnoses to consider are provided below.

- Neonates: Congenital abnormalities, such as laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia, and subglottic stenosis, typically manifest within the first month of life. Bronchogenic cysts and laryngeal clefts may become apparent in infancy and early childhood.

- Infants and toddlers: The most common causes in this age group are croup and foreign body aspiration. Epiglottitis, although uncommon, remains a potential consideration.

- School-aged children and adolescents: These children often face an increased risk of vocal cord dysfunction and peritonsillar abscesses.

- All ages: In individuals of all ages, it is crucial to consider anaphylaxis and bacterial tracheitis as significant potential factors.

- Acute: In cases of acute onset, epiglottitis and bacterial tracheitis typically manifest with severe respiratory distress and secretions, followed by fever. If fever is absent, it may indicate the possibility of foreign body aspiration or anaphylaxis.

- Subacute: In subacute scenarios, croup tends to be characterized by intermittent stridor.

- Chronic: In chronic cases, potential causes of stridor encompass laryngomalacia, vocal cord dysfunction, and tracheomalacia.

Associated Symptoms

- Hives: Hives should prompt an evaluation for anaphylaxis, which may be secondary to an allergic trigger.

- Cough: The presence of a barking cough is characteristic of croup.

- Drooling: When drooling accompanies a muffled voice, it suggests that the obstruction is likely supraglottic, such as a retropharyngeal abscess or epiglottitis. On the other hand, drooling with dysphagia may indicate the possibility of foreign body aspiration or an external abnormality compressing the esophagus.

- Mental status: An altered mental state, particularly when accompanied by increased work of breathing, can serve as a warning sign of an impending loss of airway.

- Stridor during feeding: Stridor during feeding should prompt consideration of tracheoesophageal fistula, gastroesophageal reflux, or swallowing dysfunction as potential underlying issues.

- Fever: Fever can be present with croup, epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis, and retropharyngeal abscess. Children who exhibit signs of toxicity and have a high fever are at a higher likelihood of having a bacterial infection.

Physical Examination

General: Comparing a patient's height and weight to their previous values is essential. Acute weight loss may indicate an acute issue, while failure to thrive could imply a chronic cause of stridor.

Skin: Healthcare providers should assess patients for any hives or swelling of the neck or soft tissues in the oropharynx. Furthermore, they should inspect the skin and nails of patients for signs of hemangiomas, café au lait spots, lymphadenopathy, and clubbing. These observations suggest a hemangioma in the airway, neurofibromas, infection or tumor, and congenital heart disease, respectively.

Otolaryngology: Healthcare providers should assess the tongue size and pharynx of patients for signs of edema or a peritonsillar abscess. They should exercise caution when examining the oropharynx of a patient suspected of having epiglottitis and conduct the assessment in a controlled setting, such as the operating room.

Respiratory: Healthcare providers should assess the rate and depth of breathing and auscultate for both inspiratory and expiratory stridor. In addition, it is recommended to auscultate over the anterior neck for the best detection of stridor.[4] In a child, the preference to sit up or assume a "tripod" position raises suspicion for epiglottitis. However, this positioning can also be observed in the presence of any significant airway obstruction. Infants, on the other hand, may extend their necks backward.

Evaluation

The initial evaluation should begin with a rapid assessment of the patient's airway and respiratory effort to determine the necessity for immediate intervention. The primary objective is to ensure the patient's airway is unobstructed and adequately oxygenated. Healthcare providers should assess the patient's breathing rate and depth while also checking for signs of hypoxia, cyanosis, or any indications of respiratory fatigue.

Additional testing, including imaging, radiography, and endoscopy, may be performed for stable patients presenting with stridor. Laboratory tests, such as a complete blood cell count (CBC) with a differential, may be ordered if there is suspicion of an infectious source. The differential diagnosis can aid in distinguishing between viral and bacterial causes. In cases of classic croup presentation, a CBC is generally unnecessary. However, a rapid viral panel may be warranted to assess for parainfluenza viruses in pediatric patients necessitating hospitalization.

Radiography, which may include a lateral plain film, can be performed to evaluate the size of the retropharyngeal space. A widened space on the imaging may be indicative of a retropharyngeal abscess. The mnemonic "6 at C2, and 22 at C6" serves as a helpful reminder that, in adults, the normal retropharyngeal space should not exceed 6 mm at the level of C2 and should stay below 22 mm at the level of C6. For children, the retropharyngeal space at C6 should be limited to 14 mm or less. This imaging can also help visualize an enlarged epiglottis.

The "steeple sign," attributed to an edematous subglottic arch, is the classic radiographic sign observed on an anteroposterior view of the neck in children with croup. Although approximately 70% of children with epiglottitis may have normal neck x-rays, a defining feature of epiglottitis is the presence of a "thumb sign" resulting from an enlarged epiglottis.

A chest radiograph can detect mediastinal masses, lymphadenopathy, or foreign bodies. Notably, a negative chest radiograph does not necessarily rule out the possibility of a foreign body.[5] Before conducting any radiological studies, it is essential to assess the child for signs of impending respiratory failure. If there are concerns, it is imperative to have personnel trained in airway management accompany the child to the radiology department.

In cases of diagnostic uncertainty in a stable patient with stridor, computed tomography (CT) is a viable alternative. CT scans of the chest and neck can reveal potential sources of infection, such as cellulitis, stenotic lesions, and foreign bodies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a valuable tool for distinguishing tracheal stenosis in pediatric patients.

Laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy can help visualize the airways to establish a definitive diagnosis. Rigid bronchoscopy is particularly useful for identifying and extracting foreign bodies. In cases where the patient presents as critically ill, or when epiglottitis or bacterial tracheitis is suspected as the cause of stridor, endotracheal intubation should be promptly considered.

Treatment / Management

The management of stridor is contingent upon the underlying cause. In all cases, it is essential to perform a rapid initial airway assessment to gauge the necessity for immediate intervention. In general, when assessing and treating patients with stridor, it is advisable to observe the following precautions:[6]

- Caution should be exercised to prevent agitation in children with stridor.

- One should be vigilant for signs of rapid deterioration, as these may indicate impending respiratory failure.

- A direct examination or manipulation of the pharynx in suspected epiglottitis should be avoided. In such cases, securing the airway takes precedence over diagnostic evaluation.

- A skilled healthcare professional should accompany the patient at all times. A controlled environment, such as an operating room, may be necessary for further airway evaluation.

- Foreign body aspirations should be considered in cases where symptoms develop acutely, such as sudden coughing and choking in a previously healthy child.

- In the case of croup, beta-agonists should be avoided as they may potentially exacerbate upper airway obstruction.

- Antibiotics are necessary for bacterial tracheitis and epiglottitis.

- Both steroids and racemic epinephrine have proven to be effective for managing croup.

- Surgical drainage is necessary for retropharyngeal and peritonsillar abscesses.

- Severe laryngomalacia, laryngeal stenosis, critical tracheal stenosis, laryngeal and tracheal tumors, and foreign body aspiration require surgical correction.

Differential Diagnosis

The potential causes of stridor are extensive (refer to the Etiology section for more information on the possible causes of stridor). Notable medical emergencies include epiglottitis, anaphylaxis, bacterial tracheitis, abscesses, and foreign body aspiration. The differential can be narrowed based on the patient's presenting age and the duration of stridor presentation.

Prognosis

The prognosis for stridor is favorable when promptly and appropriately treated.

Complications

The primary complications associated with stridor include the risk of respiratory failure and potential fatality. Children with laryngomalacia may be at risk for failure to thrive, while patients with tracheomalacia may face the possibility of aspiration pneumonia.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Stridor is an abnormal, high-pitched respiratory sound produced by irregular airflow in a narrowed airway during the inspiration phase. A stridor is an indicator of partial obstruction in the upper airways. Multiple factors can contribute to the development of stridor. Some frequently encountered causes include:

- Infections such as croup, epiglottitis, peritonsillar abscesses, and retropharyngeal abscesses

- Ingestion of foreign objects or food that gets lodged in part of the airway

- Ingestion of toxic chemicals

- Airway burns

- Congenital anomalies affecting the nose, throat, larynx, or trachea

- Injuries to the jaw or neck

When a child presents with stridor, various tests may be required. By conducting x-rays and CT scans of the chest and neck, healthcare professionals can gather insights into potential infections, foreign bodies, and congenital abnormalities. Laryngoscopy allows visualization of the back of the throat, whereas bronchoscopy examines the throat, trachea, and bronchi or the tubes leading into the lungs.

The treatment for stridor is contingent on its underlying cause. If left untreated, a child might experience complete airway obstruction. Management of the condition may involve antibiotics, respiratory therapies, or steroids for certain conditions, whereas others may necessitate surgical intervention.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Individuals with stridor are at a heightened risk of developing respiratory failure. Due to the broad differential and potentially life-threatening consequences, early identification and management of the underlying cause of the condition are essential for enhancing patient care and reducing morbidity and mortality. Effective evaluation and management of stridor require the collaboration of a diverse team of healthcare professionals. This medical team should consist of primary care physicians and specialists in pulmonary, gastroenterology, cardiology, emergency medicine, and infectious disease. In addition, healthcare professionals in radiology, nursing, and respiratory therapy should possess the necessary knowledge and skills to support the team.

Clinicians must be competent to evaluate respiratory status and manage a compromised airway. When a patient arrives in a critical condition with stridor, healthcare professionals should swiftly identify signs of impending deterioration and gather the appropriate resources. Subsequently, treatment should be focused on addressing the underlying cause and the associated disease process.

A patient's medical history and physical examination, combined with severity scores and treatment algorithms, significantly contribute to enhanced diagnostic precision and favorable patient outcomes. For instance, in the case of croup, numerous clinical trials have shown that proper management can be determined based on the patient's clinical presentation and severity scores. Clinical severity scores and related treatment algorithms resulted in a reduction in endotracheal intubations and shorter hospital stays.[7] Enhancing the competence and expertise of healthcare professionals in understanding the underlying causes of stridor, adeptly assessing a patient's degree of respiratory distress, and effectively managing stridor will ultimately lead to improved patient outcomes and a reduction in morbidity and mortality.