Introduction

Subcutaneous emphysema is the de novo generation or infiltration of air in the subcutaneous layer of skin. Skin is composed of the epidermis and dermis, with the subcutaneous tissue being beneath the dermis. Air expansion can involve subcutaneous and deep tissues, with the non-extensive subcutaneous spread being less concerning for clinical deterioration. However, the development of subcutaneous emphysema may indicate that air is occupying another deeper area within the body not visible to the unaided eye. Air extravasation in other body cavities and spaces can cause pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and pneumothorax. The air travels from these areas along pressure gradients between intra-alveolar and perivascular interstitium, spreading to the head, neck, chest, and abdomen by connecting fascial and anatomic planes.[1] Air will preferentially accumulate in subcutaneous areas with the least amount of tension until the pressure increases enough to dissect along other planes, causing extensive subcutaneous spread which can result in respiratory and cardiovascular collapse.[2]

Etiology

Subcutaneous emphysema can result from surgical, traumatic, infectious, or spontaneous etiologies. Injury to the thoracic cavity, sinus cavities, facial bones, barotrauma, bowel perforation, or pulmonary blebs are some common causes. Iatrogenic causes may occur due to malfunction or disruption of the ventilator circuit, inappropriate closure of the pop-off valve, Valsalva maneuvers that increase thoracic pressure, and trauma to the airway. Air may enter into the subcutaneous spaces via small mucosal injury in the trachea or pharynx during traumatic intubation, overinflation of endotracheal tube (ET) cuffs, or increased airway pressure against a closed glottis.[3] Injury to the esophagus during gastric tube placement can also create communicating entry points for air passage.[4] Air can enter the subcutaneous tissue via the cervical soft tissues during tracheotomy, via the chest wall during arthroscopic shoulder surgery, via the extremities as a result of industrial accidents, via bowel or esophageal perforation without pulmonary injury, or via a tube thoracostomy track or in the course of central venous access procedures, or percutaneous or transbronchial lung biopsy. Subcutaneous emphysema has also been observed following the insufflation of air during the course of modern era laparoscopy, and via the female genital tract during a pelvic examination, douche, postpartum exercise, or blowing into the vagina, especially during pregnancy.

The positive pressure applied by ventilator inspiration can promote the expansion of the gas through the communicating fascial planes down the partial pressure gradient. While non-invasive ventilation correlates with lower rates of barotrauma, bag-mask ventilation in CPR and incorrect oxygen mask attachment that prevents exhalation may have devastating outcomes.[5] There have also been case reports of epidural emphysema that migrates subcutaneously during "air loss of resistance" technique for epidural catheters.[6] In another case report, a patient developed massive bilateral subcutaneous emphysema without evidence of pneumothorax with post-operative nausea and vomiting.[4]

Epidemiology

The incidence of subcutaneous emphysema is anywhere from 0.43% to 2.34%.[7] In a study that classified subcutaneous emphysema over 10 years, observers noted that the mean age of patients with subcutaneous emphysema was 53 +/- 14.83 with 71% of patients that were male.[7] Approximately, 77% of patients who undergo laparoscopic procedures develop subcutaneous emphysema, although not always clinically detectable.[8] Pneumomediastinum, closely linked with the development of subcutaneous emphysema, has an incidence of 1 in 20000 in children during an asthma attack, with children under 7 years of age being more susceptible.[9] Women in the second stage of labor may also experience subcutaneous emphysema from pushing, which can increase intrathoracic pressure to 50cmH20 or greater, with the incidence being 1 per 2000 worldwide.[10] Pulmonary barotrauma in mechanical ventilation ranged from 3 to 10% depending on the initial medical indication for intubation.[11] Tracheal injury from traumatic endotracheal intubation occurs more commonly in women and individuals over 50 years old.[12] Tracheal injury during endotracheal intubation has an estimated incidence of .005%.[13] The risk of injury associated with a single lumen ET tube ranges from 1 in 20000 to 1 in 75000 and increases for double-lumen ET tubes to 0.05 to 0.19%.[14] Emergency intubation is also an associated risk factor for tracheal tear.[13]

Pathophysiology

The development of subcutaneous emphysema is thought to be caused by the following mechanisms[15][1][15]:

- Injury to the parietal pleura that allows for the passage of air into the pleural and subcutaneous tissues

- Air from the alveolus spreading into the endovascular sheath and lung hilum into the endothoracic fascia

- The air in the mediastinum spreading into the cervical viscera and other connected tissue planes

- Air originating from external sources

- Gas generation locally by infections, specifically, necrotizing infections

History and Physical

Obtaining full history is critical to explore the causes of subcutaneous emphysema and its complications. On physical examination, the most common finding associated with subcutaneous emphysema is crepitus on palpation. Distention or bloating may be present in the abdomen, chest, neck, and face. Palpebral closure resulting in visual distortion and phonation changes from vocal cord compression may also be present.[15][16] By palpating the affected area, a crackling sound and sensation (crepitus) are elicited. According to Medeiros, subcutaneous emphysema can also be appreciated by placing a stethoscope on the skin and thus emitting a high-frequency acoustic sound.[17] However, crepitus is not in itself, a pathognomic finding for deeper structure air extravasation; although, it is a likely indication that air in another connecting fascial plane exists such as the mediastinum or pleura. For patients that have extensive subcutaneous emphysema, hemodynamic or respiratory compromise may occur which is why it is imperative to investigate the cause of subcutaneous emphysema in each patient.

Grading classifications that help evaluate the extent of subcutaneous emphysema have received validation in some studies; however, it is not universally implemented or routinely used.[7]

There are suggestions that patients who use inhalational corticosteroids may be at increased risk for tracheal injury with endotracheal intubation due to friable and thin mucosa.[14] It is necessary to get a thorough medication history from patients, especially those with asthma or COPD who are already at increased risk of developing subcutaneous emphysema.

Evaluation

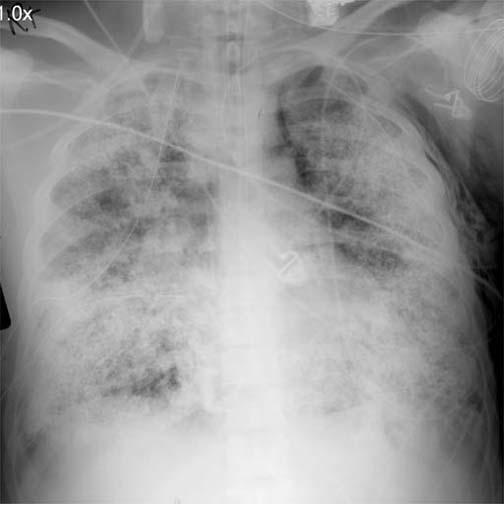

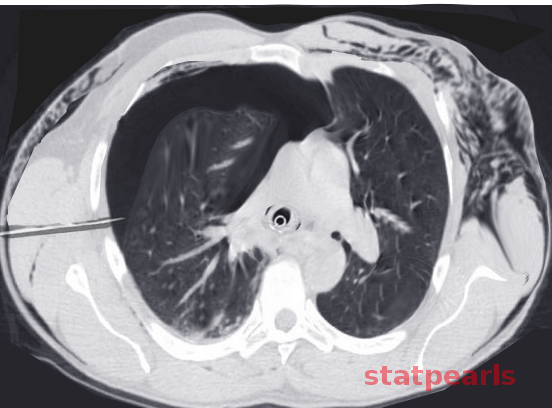

Imaging including radiographic (X-ray) and computed tomography (CT) can help identify subcutaneous emphysema. On a radiograph, there are intermittent areas of radiolucency, often representing a fluffy appearance on the exterior borders of the thoracic and abdominal walls. On chest radiograph, a ginkgo leaf sign may be present, showing striations of gas along the pectoralis major, resembling that of a ginkgo leaf.[17] In addition to X-rays, CT will show dark pockets in the subcutaneous layer indicative of gas. CT may be sensitive enough to identify the source of injury causing the subcutaneous emphysema that may otherwise not be visible on an AP or lateral X-ray.

If cervical or facial subcutaneous emphysema develops during patient intubation, it is recommended to perform laryngoscopy before extubation to evaluate for impending airway compromise or pharyngeal emphysema.[18] Additionally, if there is suspicion of airway injury as a result of intubation, bronchoscopy can help identify the location of the tracheal injury. Although air acts as a sound barrier when using ultrasound, subcutaneous emphysema may demonstrate by hyperechoic scattered densities. By placing the ultrasound probe on a region of skin without emphysema, pneumothorax is diagnosable by the absence of lung sliding and A-lines with 95% sensitivity.[19]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of the underlying cause or precipitating factor should be considered first because it usually leads to gradual resolution of the subcutaneous emphysema. For mild cases that do not cause significant patient discomfort, observation is appropriate.[7] Without compartment or deep tissue involvement, seen after exploratory laparotomy, for example, abdominal binders have been used for patient comfort. Resolution of subcutaneous emphysema will likely resolve in less than 10 days if source controlled.[20] In patients that experience continued discomfort or that require expedited resolution, high-concentration of oxygen is a well-known treatment, allowing for nitrogen washout and diffusion of gas particles in a patient with concomitant pneumothorax and/or pneumomediastinum.[21]

During endotracheal intubation, trauma can occur to the posterior trachea, causing a linear laceration of the mucosa. A tracheostomy may be required to bypass the tear and prevent further subcutaneous emphysema expansion or additional complications.[14] In mucosa tears, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics may also be of benefit to prevent the development of mediastinitis.[14] For mechanically ventilated patients, reducing tidal volume, reducing positive end-expiratory pressure, and minimizing bronchospasm and air trapping can halt the progression and promote reabsorption. [22]

During laparoscopic procedures, insufflated CO2 management is typically done by increasing the minute ventilation. However, patients that develop slow onset and delayed hypercarbia despite minute ventilation adjustment may have CO2 escape into the subcutaneous layers.[18] Therefore, post-operatively, in a patient that develops subcutaneous emphysema, be diligent in airway assessments, consider reintubation versus delayed extubation for airway protection and treat the respiratory acidosis/hypercapnia that may result from gas absorption.

In patients with extensive subcutaneous emphysema, there are reports that 2cm infraclavicular incisions bilaterally can reduce further subcutaneous expansion.[7] In a case report, a patient with extensive subcutaneous emphysema following thoracostomy had successful treatment with a subcutaneous drain placed superficial to the pectoral fascia on low suction.[23] Most experts reserve invasive therapy for cases of increasing airway impingement or cardiovascular compromise.

Differential Diagnosis

In limited case reports, subcutaneous emphysema has been mistaken for allergic reactions and angioedema after a patient presented with difficulty breathing and facial swelling.[24] The physical examination can assist in differentiating between the two as subcutaneous emphysema demonstrates lip sparing.[24] While non-extensive subcutaneous emphysema is not life-threatening, it can be a clue to other life-threatening conditions that must be investigated and excluded including esophageal rupture, pneumothorax, tracheal/bowel/diaphragm perforation, and necrotizing infections.[4] It is also crucial after intubation on a mechanically ventilated patient to not assume barotrauma from alveolar injury as the source of subcutaneous emphysema but to also examine for tracheal tears from traumatic intubation.[25]

Prognosis

The majority of subcutaneous emphysema is nonfatal and self-limited.[7] Even in cases of positive pressure mechanical ventilation, subcutaneous emphysema is considered benign, and ventilation adjustments are not necessary.[25] However, in cases of rapid and extensive gas expansion, it can be life-threatening. Massive subcutaneous emphysema can cause compartment syndrome, prevention of thoracic wall expansion, tracheal compression, and tissue necrosis. In these dreaded complications without intervention, respiratory and cardiovascular compromise can occur.[7] The gaseous expansion will also be accelerated with the use of nitrous oxide and positive pressure ventilation, hastily worsening the prognosis and likely contribute to increased morbidity and mortality.[22]

Complications

Tense and extensive air expansion in the subcutaneous tissues can prevent the thoracic cavity from expanding, reaching appropriate tidal volumes, resulting in desaturations, respiratory compromise, and dreadful cardiac arrest.[15][23] Extension of air into the neck can cause dysphagia and compression or closure of the airway. On ventilatory support, if unable to reach appropriate tidal volumes, this may lead to high peak pressures and precipitate barotrauma or expanding pneumothorax. If subcutaneous emphysema obstructs the thoracic outlet, it can prevent adequate airflow, reduce cardiac preload, and result in poor cerebral perfusion.[25] Subcutaneous air expansion into the genitals can disrupt the delicate vasculature supplying these areas causing skin necrosis.[7] In patients with pacemakers, it may cause dysfunction in the device due to air trapping within the pulse generator.[26]

Consultations

Consultation placed to other specialists is dependent on the source of subcutaneous emphysema identified. For example, if there is a tracheal tear, a thoracic surgeon should be consulted. If bowel perforation is suspected, the recommendation is for a general surgery consultation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

For patients with limited subcutaneous emphysema, education can help provide significant relief. Instructing patients that the air may cause discomfort and abnormal sounds with touch, is a benign process that will quickly resolve. In cases of palpebral closure, educating that this is a reversible cause of vision loss due to eyelid swelling may alleviate concerns. For cases of massive subcutaneous emphysema, discussing decompression techniques and the possible sequelae will enable the patient to make informed decisions about their care. Furthermore, when consenting patients for general anesthesia, communicating the risk of subcutaneous emphysema will increase awareness of expected management if subcutaneous emphysema does develop.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Care from different members of the health care team including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health care professionals provide different perspectives and skillsets in patient evaluation, management, and treatment of subcutaneous emphysema when all caregivers work collaboratively. In the post-anesthesia care or critical care unit, nurses can outline gaseous spread with a pen, watch vital signs, and monitor the patient more frequently than a physician. Grading the degree of subcutaneous emphysema can be easily done at the bedside.[7] Physician specialist involvement is also imperative to ensure comprehensive care of the patient including recognizing the patients with high risk to develop subcutaneous emphysema. The radiologist can detect the presence of subcutaneous emphysema that may not be detectable on an exam and identify a likely source of gaseous spread. The thoracic, general, or other surgical specialists can monitor progression intraoperatively as well as provide surgical fixation for the source of subcutaneous emphysema if necessary. Anesthesiologists perform pre-operative risk assessment using ASA grading system, secure compromised airways, manage ventilator settings, as well as perform bronchoscopies and transesophageal echocardiograms for diagnostic evaluation.[27] [Level 3] Anesthesia assistants can help troubleshoot ventilators when a faulty valve or connection may be present. Respiratory therapists can help with ventilator management, non-invasive oxygenation therapies for patients requiring respiratory support, to avoid under and overinflation of the ET tube, to avoid adjusting the ET tube without cuff deflation. Pharmacists can help advise escalation of antibiotic therapy in aggressive necrotizing infections causing subcutaneous emphysema.

Subcutaneous emphysema may be a self-limited process or a medical/surgical emergency requiring intervention. An interprofessional and interprofessional approach offers significant value when diagnosing and managing patients with subcutaneous emphysema.[Level 5]