Introduction

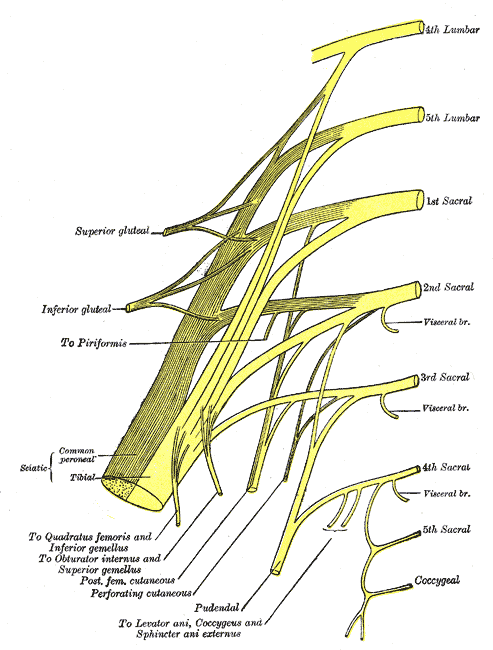

The superior gluteal nerve is found in the lower pelvis and arises from the dorsal divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus. The superior gluteal nerve is responsible for innervation of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. The nerve exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen superior to the piriformis muscle and accompanies the superior gluteal artery and vein. The superior gluteal nerve further divides into a superior branch and an inferior branch, with each branch following the course of the superior gluteal artery’s upper and lower portions of the deep division, respectively.[1] Damage to the superior gluteal nerve results in paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle resulting in a characteristic gait on walking and standing known as the Trendelenburg gait.

Structure and Function

The superior gluteal nerve provides innervation to the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. The gluteus medius is responsible for hip joint abduction and works in conjunction with the gluteus minimus and tensor fasciae latae. The gluteus minimus not only allows for hip abduction but is also integral to medial rotation of the thigh due to its anterior component. The tensor fasciae latae, on the other hand, provides traction on the iliotibial tract, thereby assisting in hip extension via the gluteus maximus muscle. Together, all three components comprise the abductor mechanism, which stabilizes the pelvis during the single leg phase of gait while enabling foot clearance during the swing phase.[2]

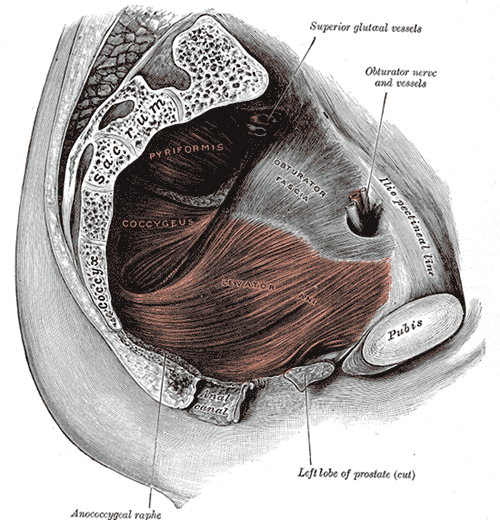

The superior gluteal nerve originates from the posterior divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus, and accompanies the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus. The nerve then travels posterolaterally, eventually leaving the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen accompanied by the superior gluteal vessels. The superior gluteal nerve is unique in that it is the only nerve to exit through the greater sciatic foramen superior to the piriformis muscle. All other nerves which exit through the greater sciatic foramen, such as the pudendal nerve, inferior gluteal nerve, and sciatic nerve, do so inferior to the piriformis. It then enters the gluteal region and travels over the inferior aspect of the gluteus minimus, then courses anteriorly and laterally within the plane between the gluteus minimus and gluteus medius muscles, with branches terminating in the tensor fasciae latae muscle.

Superior to the piriformis muscle the superior gluteal nerve divides into its superior branch and inferior branch. The superior division travels with the upper component of the deep division of the superior gluteal artery and innervates the gluteus medius and occasionally the gluteus minimus as well. The superior gluteal nerve courses across the deep aspect of the gluteus medius at an estimated 5cm above the tip of the greater trochanter.[1] The inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve, on the other hand, accompanies the lower portion of the deep division of the superior gluteal artery, and travels across the gluteus minimus, innervating this muscle as well as the gluteus medius. The inferior branch eventually terminates in and innervates the tensor fasciae latae muscle.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superior gluteal nerve, with its close relation to the superior aspect of the piriformis, accompanies the superior gluteal artery and vein. The superior gluteal artery is the largest of the branches of the internal iliac artery and exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle. The superior gluteal veins run along with the superior gluteal artery and drain into the hypogastric or internal iliac vein.

Once past the notch, the superior gluteal artery divides into a superficial branch which supplies the gluteus maximus, and a deep branch which is found deep to the gluteus medius and subdivides into the superior and inferior divisions. The superior division travels along the superior border of the gluteus minimus towards the anterior superior iliac spine, eventually anastomosing with the deep iliac circumflex artery as well as the ascending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery. Moreover, the inferior division travels in an oblique fashion across the gluteus minimus towards the greater trochanter, subsequently giving off branches to the gluteal muscles and anastomosing with the lateral femoral circumflex artery. Hence, the superior gluteal artery is involved in the trochanteric anastomoses, providing a connection between the internal iliac and femoral arteries.

The superior gluteal artery passes out of the pelvis at a rather acute angle, which increases its vulnerability to a shearing force. The artery may also be compromised by the sharp fascia of the piriformis muscle during displaced fractures. Surgical procedures involving the greater sciatic foramen places the superior gluteal artery at risk for injury as well.[3][4][3]

Muscles

The gluteus minimus, gluteus medius, and tensor fasciae latae muscles receive innervation from the superior gluteal nerve. Functionally, both the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles are integral to the gait cycle as they provide a significant stabilizing force during the terminal swing phase. Damage to this nerve results in characteristic loss of motor function that presents as a disabling gluteus medius limp, a phenomenon known as the Trendelenburg or gluteal gait. In this condition, the weakened gluteus medius muscle causes a shift in the center of gravity to the unaffected limb. Bilateral superior gluteal nerve lesions often result in a waddling gait.

The gluteus medius is a thick, fan-shaped muscle originating from the outer aspect of the ilium superiorly from the iliac crest, the middle gluteal nerve inferiorly and the gluteal line posteriorly. The muscle then travels inferolaterally towards the lateral surface of the greater trochanter. The gluteus medius works synergistically with the gluteus minimus and tensor fasciae latae to allow for forceful hip abduction. The anterior fibers of the gluteus medius enable medial rotation of the thigh as well. Functionally, the gluteus medius muscle works with the gluteus minimus and tensor fasciae latae to allow walking and running. While walking or running, the lower extremity limb not in contact with the ground does not tilt downwards due to the contraction of the contralateral gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae.

Similarly, the gluteus minimus is also a fan-shaped muscle located deep to the gluteus medius, arising from the lateral aspect of the ilium between the inferior and middle gluteal lines. The muscle fibers travel inferolaterally towards the anterior surface of the greater trochanter. The function of the gluteus minimus mirrors that of the gluteus medius and is responsible for hip abduction and medial rotation of the thigh.

The tensor fasciae latae is a small muscle found between the iliac tubercle and anterior superior iliac spine, originating from the outer aspect of the iliac crest. The muscle travels inferiorly and posteriorly and is encased within a sheath composed by the iliotibial tract of the fascia lata located on the lateral thigh. The tensor fasciae latae allows traction on the iliotibial tract, assisting the gluteus maximus with hip and knee extension. This action is crucial in maintaining the knee in the fully extended position.

Physiologic Variants

There has been documented variation in the course of the superior branch of the superior gluteal nerve, specifically that of the superior branch traversing below the inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve. This superior branch descended inferolaterally, entering the tensor fasciae latae.[5] However, a more common variation observed was the distribution of the nerve around the greater trochanter. Moreover, cadaveric dissections have revealed that the superior gluteal nerve divides into the typical two branches in 86.20% of cases, while it further subdivides into three branches in 13.8% of cadavers.[6]

An aberrant double belly composition of the piriformis muscle with the superior gluteal nerve trapped between the two muscle bellies has been observed. This observation suggests a unique anatomical variant that may serve as a rare cause of piriformis syndrome and undiagnosed chronic gluteal pain.[7]

Surgical Considerations

Injury to the superior gluteal nerve can be due to hip dislocation, hip fractures, hip arthroplasty, and intramuscular injection into the buttocks. There are various etiologies of hip pain, such as arthritis, tendonitis, bursitis, and fractures. Surgical management of osteoarthritis of the hip joint has evolved in the past several years. With new surgical reconstructive techniques, the splitting and reflection forward of the anterior aspect of the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis is carried out as a single sheet which is subsequently reattached to the greater trochanter. However, these types of procedures are not without with complications, such as damage to neurovascular structures and infections.[5] Importantly, if the splitting of the gluteus medius muscle is greater than a few centimeters (typically 5cm) superior to the tip of the greater trochanter, then the risk of injury to the superior gluteal nerve and superior gluteal vessels is increased.[8] The incidence of injury to the superior gluteal nerve is dependent mainly on its course and branching pattern. During approaches to the hip joint, it is essential to define the nerve’s distance from the greater trochanter and the safe area for the superior gluteal nerve. The safe area for the superior gluteal nerve in hip surgeries is defined as 4cm from the tip of the greater trochanter for the anterior third, and 5cm for the posterior and middle third of the gluteus medius. Moreover, it was found that the average distance between the gluteus medius innervation point and the greater trochanter fluctuate as a function of body height. Therefore, the risk of neural injury is increased in hip procedures using a direct lateral approach, which is also known as the Hardinge approach to the hip.[8]

Furthermore, abduction weakness and limping are common complications of closed antegrade insertion of femoral nails and are most likely caused by iatrogenic injury to the superior gluteal nerve and gluteus medius itself. However, by increasing the degree of hip flexion and adduction during insertion of a femoral nail, the injury risk to the superior gluteal nerve and gluteus medius is lowered.[9] The positioning of the hip can help to achieve the appropriate degree of hip flexion and adduction, with higher degrees of these movements achievable with either the lateral position on a fracture table or “sloppy” lateral position on an ordinary table.

The gluteal region is also a common location used for the administration of drugs, particularly when the rapid action of the drug is required or if the drug is not viable via the intestinal route. The injection should be administered in the superolateral quadrant of the buttock to avoid the branches of the superior gluteal nerve as well as the sciatic nerve, typically located in the lower quadrants of the buttock.

Clinical Significance

During normal gait, the small gluteal muscles on the standing leg help stabilize the pelvis in the coronal plane. If there is paralysis or weakness of the muscles as a result of injury to the superior gluteal nerve, it can result in a weakened abduction of the affected hip joint. This type of gait deficit is known as the Trendelenburg gait. When the patient is standing on one leg, the opposite pelvis should be lifted upwards by abduction of the ipsilateral hip joint. When the abductors are weak due to superior gluteal nerve paresis, the pelvis will sag which is the basis of the positive Trendelenburg sign. In a patient with a positive Trendelenburg sign, the pelvis sags toward the normal unsupported side, which is the swing leg. When the opposite occurs, and the pelvis raises on the swing side, the deficit is known as the Duchenne limp — bilateral damage to the superior gluteal nerve results in a “waddling” or gluteal gait. Also, the patient may raise the foot of the unsupported side during ambulation as the leg swings forward, leading to a steppage gait. A swing-out gait occurs when the foot on the unsupported side swings out in the lateral direction.

Other Issues

The integrity of the superior gluteal nerve is clinically assessed by observing pelvis and hip stabilization and gait. The patient, if able to stand unaided, is asked to stand upright with their feet together and then asked to raise one foot while balancing on the other. This maneuver can then repeated on the opposite side. Normal findings would include positional stabilization of the hips bilaterally when lifting one foot from the ground. A slight raising of the unsupported hip is within normal limits.

Since the gluteal region is a common site for drug administration, it is essential to be aware of possible complications that may arise, such as damage to the superior gluteal nerve, pain, infection, hematoma, abscess formation, lipodystrophy, and intramuscular bleeding.