Introduction

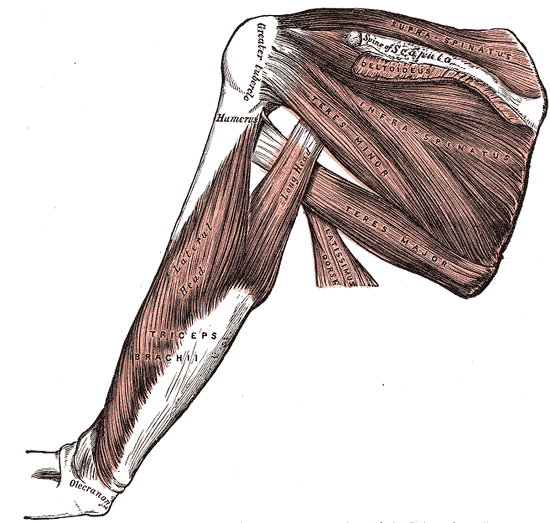

The supraspinatus muscle, the most superiorly located of the rotator cuff muscles, resides in the supraspinous fossa of the scapula, superior to the scapular spine. The tendon of the muscle extends laterally, passing under the acromion process and over the head of the humerus, blending into the glenohumeral joint capsule to insert onto the superior facet of the greater tuberosity of the humerus. In conjunction with the other three rotator cuff muscles, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, the supraspinatus forms part of the dynamic stabilization for the glenohumeral joint.

These four muscles act in a coordinated fashion to stabilize the head of the humerus on the shallow glenoid fossa and promote the structural integrity of the joint. Along with its role as a stabilizer, the actions associated with supraspinatus are abduction of the humerus, which may contribute weakly to the lateral rotation of the humerus. As the most frequently torn rotator cuff muscle, the supraspinatus has been the subject of extensive research. Much is known, yet much is left to learn about this small but important muscle.[1]

Structure and Function

The architecture of the supraspinatus muscle has been described in multiple ways, from fusiform to circumpennate. A more detailed analysis of the structure through MRI studies reveals the complexity of the architecture. In 1993, the supraspinatus was described as including anterior and posterior muscle bellies. Further research has demonstrated that the two bellies differ in function. Roh et al. described the structure of the supraspinatus muscle and found that the tendon of the anterior belly as thicker and more tubular in structure, whereas the posterior tendon was flatter and wider in each of the 25 embalmed cadaveric shoulders they examined.[2] They determined the ratio between the mean anterior and posterior muscle belly physiologic cross-sectional area to be 2.45 to 1. Furthermore, the authors noted the ratio for the tendon cross-sectional area for the anterior and posterior bellies to be 0.9 to 1. This ratio indicates that the greater muscle mass in the anterior belly exerts its force through a smaller cross-sectional area of the tendon than the posterior belly.

While it is noteworthy that in the literature, there is no agreement regarding the determination of tensile load from the physiologic cross-sectional area, the authors assumed a linear relationship between the two variables utilizing ratios rather than absolute values. Based on the ratios noted, the authors concluded that the anterior tendon would experience as much as 288% more stress than the posterior tendon.

Roh et al. defined the structure of the anterior belly as fusiform with an origin entirely from the supraspinous fossa.[2] The anterior belly contained an internal tendon that forms a tendinous core into which the muscle fibers insert. The internal tendon thickened into a tubular structure as it became extra-muscular. The tendon from the anterior belly supplies forty percent of the overall width of the external tendon. The posterior belly differed in structure from the anterior belly and is described as unipennate; a structure is less compatible with the generation of large contractile loads. The posterior belly was more of a strap-like (Vahlensieck) muscle, originating from the spine of the scapula and neck of the glenoid, and was devoid of an internal tendinous core.

The muscle fibers of the posterior belly inserted directly into the flatter, thicker external posterior tendon comprised 60% of the thickness of the supraspinatus tendon. The authors further calculated the tendon stress attributed to the anterior and posterior muscle bellies indicating the anterior tendon is subjected to 2.88 times greater stress than the posterior tendon. They also noted the histologic intratendinous structural differences between the two portions of the supraspinatus tendon, with the anterior portion of the tendon demonstrating a double-layered interwoven pattern of fibers versus thin, dispersed fibers in the posterior division of the tendon. This finding supported the force calculations of the study.

Fallon et al. examined the histological morphology of the supraspinatus tendon and identified four structural subunits within the tendon: tendon proper, attachment fibrocartilage (approx. 2.8 cm in length), rotator cable (extension of the coracohumeral ligament), and capsule.[3] The tendon proper portion extended from the musculotendinous junction to the attachment fibrocartilage. The dissection noted the more tubular, "rope-like" structure of the anterior tendon and the "thin strap-like" posterior portion that together created a wide point of attachment on the greater tuberosity. The collagen fibers and fascicles were noted to be in a parallel arrangement to the "axis of tension," and histological staining indicated the presence of an abundance of negatively charged glycosaminoglycans which were noted to be areas where the individual fascicles moved against and were easily separated from each other. The fascicular arrangement in the tendon proper changed to a basket-weave pattern of the attachment fibrocartilage more proximally in the anterior tendon than in the posterior tendon. The attachment fibrocartilage region was histologically similar to fibrocartilage which is subject to compressive forces. The rotator cable was identified as an extension of the coracohumeral ligament that is positioned perpendicular to the axis of the tendon proper, located between the tendon and joint capsule. The joint capsule was found to be a composite of thin collagen sheets, with collagen fiber orientation consistent within sheets but varied between layers. When joined together, the sheets create a thin but strong structure with collagen fibers of varied arrangements. The attachment fibrocartilage and the capsule are inseparable at a point just medial to the supraspinatus tendon insertion on the greater tuberosity.

The supraspinatus muscle and tendon both pass deep to the acromion process to insert onto the super facet of the greater tuberosity of the humerus — the inferior portion of the tendon blends with the joint capsule about 1 cm before the attachment on the bone. The superior portion of the tendon is contiguous with both the coracohumeral and transverse humeral ligaments. This position and location allow the muscle to perform the function of abduction of the humerus. Along with deltoid, supraspinatus has motor involvement with both the initiation and continuation of abduction throughout the range of motion. The supraspinatus has also been shown to contribute weakly to the lateral rotation of the humerus. Along with the other rotator cuff muscles, supraspinatus stabilizes the humerus head on the glenoid fossa during joint movements and acts with the deltoid to limit inferior displacement of the humeral head.[4]

Embryology

The development of the pectoral girdle and upper limb bud muscles have separate sources of origin. The scapula and muscles that attach to the medial border of the scapula are derived from para-axially located somites, whereas most of the limb bud structures of the upper limb are derived from lateral plate mesoderm, which develops opposite somites 8 to 10. Additionally, the connective tissue, which encompasses the entire pectoral girdle and maintains the integrity of the structure with the axial skeleton, is continuous with the connective tissue of the limb and superficial tissues of the thoracic region.[5]

Upper limb development generally precedes lower limb bud development by several days. Precursor myoblasts of the upper limb migrate from multiple sources to form dorsal and ventral pre-muscle masses of the limb bud in stage 12, approximately week 5 of development. Supraspinatus will arise from the cells in the dorsal pre-muscle mass. The muscles of the upper limb form as a combination of somatic cells (muscle cells and myosatellite cells) and somatopleuric cells (tendons and other connective tissue structures). As the embryo reaches approximately 11 mm in length, the spine of the scapula and acromion are forming, and at the same time, the cellular mass of the deltoid starts to develop. Between the 11 mm and 15 mm embryonic stage, the deltoid mass transects horizontally, forming a myoblast mass that will become supraspinatus and infraspinatus. This embryologic association is important to the dynamic control of the glenohumeral joint.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The supraspinatus receives its blood supply from the suprascapular and the dorsal scapular arteries.[7] The suprascapular artery is typically a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, a branch of the subclavian artery, though it may arise directly from the third part of the subclavian artery. The suprascapular artery passes inferolaterally over the anterior scalene and phrenic nerve, deep to the internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid, then superior to the subclavian artery and brachial plexus. The artery will ultimately reach the superior border of the scapula, where it will generally pass superior to the superior transverse ligament to reach the supraspinous fossa. It will supply both supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The dorsal scapular artery originates from the subclavian artery, most frequently the third part. It will travel posteriorly through the trunks of the brachial plexus, over the middle scalene muscle, then deep to the levator scapula to reach the superior angle of the scapula, where it will begin traveling with the dorsal scapular nerve. This artery will anastomose with the suprascapular and the subscapular arteries and supply the muscles in the area.

Superficial lymphatic drainage generally follows the veins, and deep lymphatic drainage typically follows the arteries. Lymphatic drainage of the suprascapular region is primarily through the posterior subscapular nodes, which are located along the inferior margin of the posterior axillary fold and are associated with the subscapular vessels. The efferent drainage from these nodes will be to the central axillary nodes, followed by the apical nodes. The efferent vessels combine to form the subclavian lymphatic trunk, which will drain either to the jugulosubclavian venous junction, the subclavian vein, the jugular lymphatic trunk, or occasionally a right lymphatic trunk. The left trunk drains into the thoracic duct.

Nerves

Supraspinatus receives its nerve supply from the suprascapular nerve (C5-C6), a branch of the upper trunk of the brachial plexus.[8]

Muscles

The supraspinatus has associations with the other muscles of the rotator cuff, including infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. It is embryologically linked to the deltoid and works with the deltoid to perform abduction of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint.[5] The rotator cuff muscles, together with the deltoid and the long head of the biceps brachii, for the dynamic stabilization of the glenohumeral joint.

Physiologic Variants

Research studies of MRI images show an aponeurotic expansion of the supraspinatus tendon adjacent to the bicipital groove in about 50% of the images studied. This tendon-like structure arose from the anterior portion of the supraspinatus tendon passed distally in a parallel orientation anterolateral to the long head of the biceps tendon with a distal insertion on the superior aspect of the tendon of the pectoralis major. The theory is that this aponeurotic expansion may reinforce the anterior tendon, which has a small footprint of insertion on the greater tuberosity and serve a similar function as the rotator cable of the rotator cuff interval.[9]

Surgical Considerations

Due to the finding of Roh et al., when attempting to repair the supraspinatus tendon, the anterior fibers need to be incorporated in the repair whenever possible to lend strength to the structure and function of the muscle post-repair.[2] The anterior fibers and the anterior tendon are responsible for the functions of glenohumeral abduction and humeral head depression. Without incorporating these fibers into the repair, there may be some functional compromise. While there have been suggestions in the literature that a torn rotator cuff may be responsible for shoulder weakness due to the decreased functional tendon length, there must also be a consideration for the loss of anterior tendon function along with the loss of the primary source of supraspinatus contractile load.[2]

Other articles address the post-surgical outcomes and functional recovery, the influence of opioids on postoperative outcomes, and a new scoring system for healing after surgical repair of a rotator cuff injury, to name a few.[10][11][12] As indicated, this is a muscle about which there is a lot of interest, and there are many published research articles about this muscle.

Clinical Significance

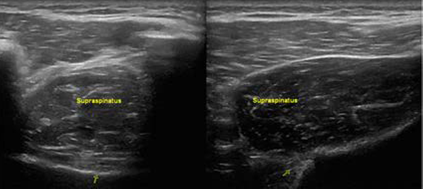

Structural differences in the anterior and posterior bellies of the supraspinatus muscle may account for functional differences noted post-injury. If the anterior fibers are spared in the injury, the ability of the individual to elevate the arm beyond 90 degrees may be less impaired than if the anterior belly is involved in the tear. Observation of the two parts of the muscle and structural integrity should be noted during surgery to understand better post-operative recovery and functional ability and facilitate appropriate rehabilitative interventions.

Communication between all segments of the healthcare team will enhance optimal outcomes for the client with a supraspinatus pathology. Understanding which part of the muscle is involved in the pathology if the rotator cuff interval is affected or closed surgically, and whether the anterior fibers were involved in the tear and repair are essential for optimal outcomes. Radiological identification, conservative rehabilitation, surgical options, and post-surgical rehabilitation depend on excellent team communication.

Other Issues

The rotator cuff interval is a region located between the supraspinatus and the subscapularis tendons. The structure and function of this interval underwent a study by Jost et al. and were found to be comprised of the supraspinatus and subscapularis and the coracohumeral ligament, superior glenohumeral ligament, and the glenohumeral joint capsule.[13] The interval was divisible into the 2-layer medial part, which was found to limit inferior translation, and the 4-layer lateral portion, subdivided into the 3-layer fibrous plate and a 1-layer lateral part, which mainly limits external rotation when the arm is adducted. The coracohumeral ligament component of the interval was found to be the key structure in the rotator cuff interval. It plays a vital role in both external rotation, inferior translation, and stability of the glenohumeral joint. The rotator cuff interval and its function in restricting movement is an important surgical consideration. Closure of the lateral part of the interval restricts the resultant external rotation range of the adducted joint. Hence, the performance of the closure should be in an externally rotated position to allow for appropriate functional return. Also, superior migration of the humerus due to rotator cuff tear or insufficiency may require the release of the medial coracohumeral ligament to keep the humeral head centrally located in the fossa.

In instances where the rotator cuff interval is contracted and limiting external rotation, the release of the lateral aspect of the interval may be an option, leaving the coracohumeral ligament intact. Lim et al. found the presence of pectoralis minor tendon inserting into the rotator cuff interval in 11 of 99 subjects studied, and the tendon tethered the retracted supraspinatus tendon in 7 of the 11 subjects, which created tension on the tendon repair and resulted in the need to resect the pectoralis minor tendon completely for optimal repair.[14]