Continuing Education Activity

Flaps, in the setting of reconstructive surgery, refer to tissue (generally including skin or mucosa) that is transferred into a defect to facilitate wound closure. They can be employed when closing wounds by second intention, primary linear closure, or when skin grafting would result in functionally or aesthetically unsatisfactory results. Transposition flaps, also called lifting flaps, recruit noncontiguous donor tissue that is incised and shifted to trade places with intact tissue in order to close a wound. Transposition flaps most commonly used in cutaneous surgery include the bilobed, rhombic, and nasolabial (melolabial) transposition flaps and z-plasties. These flaps allow the use of skin from areas of less tension and direct incision tension vectors more favorably. This activity describes the indications, contraindications, and techniques involved in using different types of transposition flaps and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients undergoing these procedures.

Objectives:

- Describe the techniques involved in rhombic, bilobed, nasolabial, and z-plasty transposition flap procedures.

- Describe the different types of transposition flaps.

- Identify potential complications of transposition flaps.

- Describe the importance of collaboration and coordination within the interprofessional team to facilitate the safe use of transposition flaps to minimize complications and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Flaps, in the setting of reconstructive surgery, refer to tissue (generally including skin or mucosa) that is transferred into a defect to facilitate wound closure. They can be employed when closing wounds by second intention, primary linear closure, or when skin grafting would result in functionally or aesthetically unsatisfactory results.[1] For these reasons, flaps are an invaluable tool for the cutaneous surgeon. They are categorized by blood supply into axial flaps, which are supplied by a named artery, and random pattern flaps, which rely on the vascular plexus of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

Overall, flaps are divided into three main categories: free flaps, in which tissue is taken from a distant site, brought to the wound, then reperfused via microsurgical vascular anastomoses; regional flaps, in which nonadjacent tissue near the defect is moved into the wound, maintaining a vascular pedicle for perfusion; and local flaps, in which adjacent tissue is transferred into the wound. By their nature, free flaps and regional flaps tend to have axial blood supplies. Local flaps, more often than not, have random blood supplies.

The type of primary movement required for transfer can further divide local flaps into three categories: advancement, rotation, and transposition. Advancement and rotation flaps, also called sliding flaps, recruit adjacent tissue and move in either a linear or arced motion, respectively, to fill in the primary defect. Transposition flaps, also called lifting flaps, recruit noncontiguous donor tissue that is incised and shifted to trade places with intact tissue in order to close a wound. Transposition flaps most commonly used in cutaneous surgery include the bilobed, rhombic, and nasolabial (melolabial) transposition flaps, as well as z-plasties. The fourth category of flap movement, interpolation, is often listed as well; however, because it involves transferring nonadjacent tissue across or underneath intact tissue that remains undisturbed by the procedure, these flaps are usually more correctly considered regional flaps.[2][3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Two major layers comprise the skin: the epidermis, superficially, and the dermis underneath. The epidermis itself contains four to five layers, depending on location in the body: stratum corneum, stratum lucidum (palms and soles of hands and feet only), stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale. The dermis is composed of a superficial papillary layer and a deeper reticular layer. The blood supply to the skin runs vertically through perforating vessels that arise from the subdermal plexus, which is located either between the dermis and subdermal fat or deep within the reticular dermis itself. Understanding the nature and location of the skin's blood supply is critical to successful flap transfer and wound healing.[5][6]

Equally critical to successful flap transfer is an understanding of relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) and lines of maximum extensibility (LME). Langer and Dupuytren observed the natural tendencies of cutaneous wounds to elongate in certain predictable patterns based on the orientation of dermal collagen bundles and of the underlying musculature. In the face, these lines are referred to as RSTLs, and they run perpendicular to the direction in which facial mimetic muscles contract. Perpendicular to the RSTLs is the LMEs, which determine in which direction the skin will stretch most effectively to fill a defect.

The viscoelastic properties of skin permit it to lengthen under constant tension, so-called "skin creep," and ultimately to maintain that increased length with progressively less tension required ("stress relaxation"). With these principles in mind, the surgeon can select an appropriate flap design that will maintain tissue perfusion, maximize skin extensibility, and minimize distortion of surrounding features (particularly on the face) by paying close attention to RSTLs and boundaries between aesthetic subunits (e.g., nose, perioral area, periorbital area, etc.), within which scars are best hidden.[7][8]

Indications

Transposition flaps are employed when surgical defects pose a risk of functional impairment and/or aesthetically displeasing results if repaired by simple primary closure, second intention, skin grafting, or sliding flaps. Advantages of transposition flaps include less undermining when compared to large, sliding flaps and superior ability to displace tension away from the defect and any nearby free margins, as well as to reorient tension vectors in more favorable directions.

Rhombic transposition flaps are particularly useful for defects near the medial and lateral canthi, cheeks, and lateral upper two-thirds of the nose, but they also have a well-defined role in the lateral forehead, temple, perioral, inferior chin, and dorsal hand defects.

Bilobed transposition flaps can be utilized in defects of the lower third of the nose, the helix, and the posterior ear. Nasolabial transposition flaps are used for medium-sized defects of the nasal ala. The z-plasty can improve the cosmesis of scars crossing RSTLs and help release scar contractures by redistributing tension over the wound.[9][10][11][12]

Contraindications

Contraindications for transposition flaps should be considered before their use in repairing a particular defect. Careful patient selection remains essential. Functional status should be assessed with close attention paid to comorbidities and the ability to care for the flap postoperatively. These procedures should be avoided in patients who are poorly compliant or cannot leave their surgical sites undisturbed. Additionally, patients who are unable to carry out post-surgical instructions due to disability or comorbidities (such as dementia) without access to other medical care should be considered poor candidates.

Other contraindications to the transfer of a flap include failure of tumor clearance and active infection involving the flap. Failure to fully clear the tumor, particularly the deep margin, can lead to recurrent tumors growing unrecognized for long periods of time along planes of undermining and ultimately cause a larger tumor burden. Local control via adequately excised margins or Mohs micrographic surgery can minimize this risk. Infected skin should never be used to fashion a flap, as this increases morbidity and complication rates, including the risk of flap failure.

Relative contraindications include smoking, bleeding diatheses, or predisposition to impaired vascular supply. Smoking increases the risk of flap necrosis, wound dehiscence, prolonged healing times, and infections. Recommending smoking cessation from two weeks prior to one week after surgery may help to minimize these complications. Patients with inherited bleeding diatheses or anticoagulation therapy are at increased risk of perioperative or postoperative bleeding and hematoma. Consultation with specialty physicians prior to operating on patients with known inherited bleeding diatheses is advised. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, when appropriately managed, are generally continued during surgery to avoid the risk of thrombotic events. The use of tissue with impaired vascular supply, such as previously irradiated skin or scar, is generally avoided as it can decrease blood flow in the pedicle and adversely affect the viability of the flap.[13][14]

Equipment

The equipment needed to perform a transposition flap is similar to that needed for other cutaneous surgery.

Preoperatively

- Alcohol solution or pad (cleanse and degrease skin prior to marking the planned flap)

- Surgical marker (for marking planned flap)

- Local anesthesia (such as lidocaine 0.5% with epinephrine 1:200,000 buffered with sodium bicarbonate in a 1:10 ratio)

- Topical antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine

- Surgical drape

Intraoperatively

- Scalpel (#15 blade)

- Forceps

- Shea scissors (or other dissecting scissors)

- Iris scissors, preferably serrated (thin fat from flap if indicated)

- Gauze

- Electrocoagulation/electrocautery device

- Skin hooks

- Needle driver

- Normal saline (keep tissue clean and moist)

- Suture (absorbable and nonabsorbable)

Postoperatively

- Petrolatum

- Non-stick dressing material

- Gauze (placed over non-stick dressing material to provide pressure and added absorbency)

- Hypoallergenic surgical tape

Personnel

At least one surgical assistant helps manage intraoperative bleeding, cutting sutures, and placing a postoperative dressing.

Preparation

Depending on the patient, it can be helpful to show or describe the size of the defect after tumor clearance and explain the chosen transposition flap and the expected scar. Addressing the patient expectations is key to proper care of the flap as well as improving the perception of the outcome. Patients often underestimate the size of the tumor, and satisfaction may be increased by encouraging them to see the size of the defect after tumor clearance to understand better why the scar appears the way that it does. Photographs should be taken of the lesion before incision, the defect after tumor clearance, and the completed repair. Typical postoperative changes and the potential need for revisions, such as laser or dermabrasion, should also be discussed.[15]

Technique or Treatment

All transposition flaps should be planned and drawn meticulously before execution, as even the smallest error in planning can have dramatic functional and aesthetic consequences. Again, complete tumor clearance before flap transfer is of the utmost importance. Previous scars, facial subunits, relaxed skin tension lines, and lines formed from facial expressions should be noted at rest and with movement.

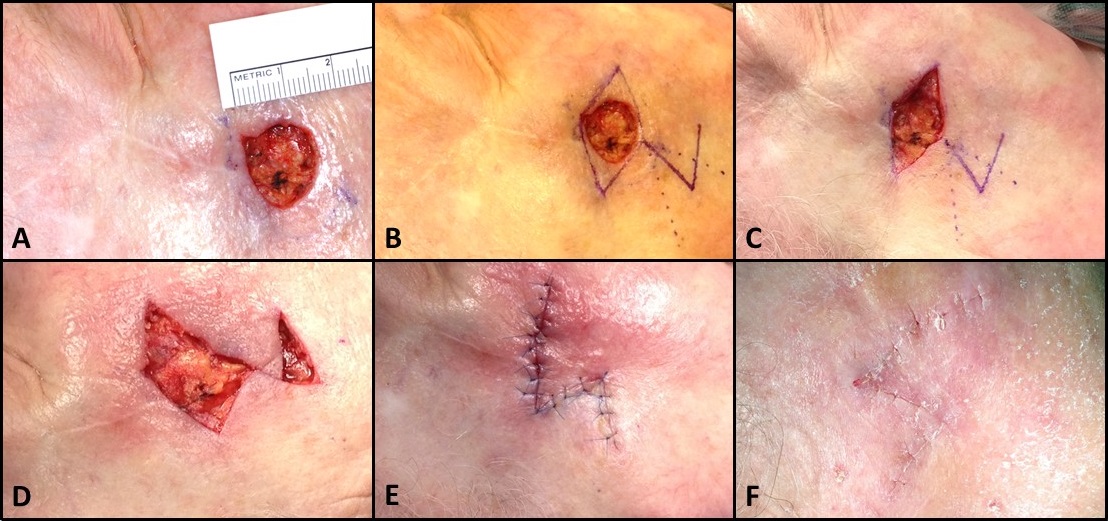

Rhombic Flap

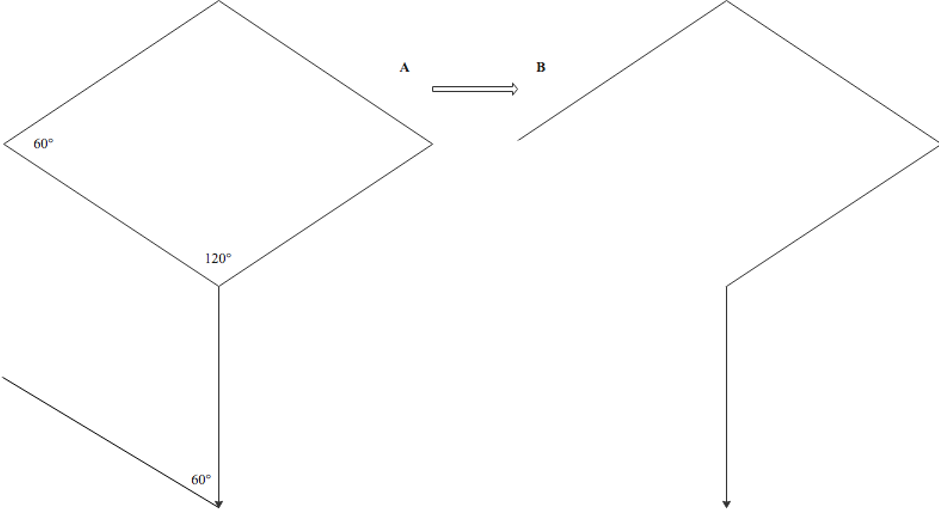

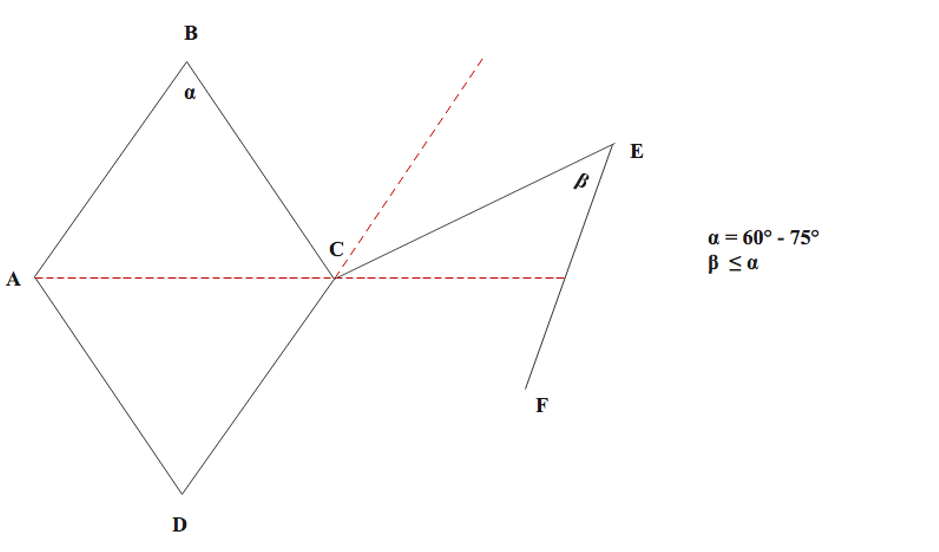

The rhombic flap was originally described by Limberg in 1966 and is often called the Limberg flap for that reason. It is particularly useful for repairing defects of the medial and lateral canthi, cheeks, and lateral upper two-thirds of the nose. It also has great utility for defects of the lateral forehead, temples, perioral region, inferior chin, and dorsal hands. In the classic Limberg design, the lesion is surgically excised (preferably with a slight outward bevel) as a rhombus with two opposing 60-degree angles and two opposing 120-degree angles. The flap is designed off the short axis of the defect. The advantages of this design include a smaller secondary defect as well as four possible arrangements of the flap, allowing surgeons to select the orientation that produces the ideal wound closure with low scar tension. The flap arrangement chosen should be designed so that the donor-site closure (secondary defect) is aligned to take advantage of the area of maximum laxity and avoid sensitive structures.

After the rhombic defect is created and the flap planned, the incision of the flap is performed with one limb that extends off the selected short axis at a 120-degree angle, equal in length to the sides of the rhombus. A second incision of equal length extends from the endpoint of the first incision to form a 60-degree angle. The flap should be undermined in the subdermal plane to ensure perfusion and lifted into the primary defect; the defect itself should be deepened, if necessary, to the level at which the flap is elevated. After wide undermining of the primary and secondary peripheral defect edges, hemostasis should be attained, and the secondary defect closed in layers using deep dermal (4-0 or 5-0) sutures and simple interrupted or vertical mattress sutures (5-0 or 6-0) superficially. The flap should then be sutured into the primary defect similarly. The finished rhombic transposition flap should look similar in shape to a question mark.

Variations of the classic Limberg rhombic flap also are common in dermatologic surgery. The Dufourmentel modification narrows the angle of the tip of the secondary defect and creates a shorter arc of rotation for the flap by incising the first line at the angle made by bisection of the first line of the Limberg and extension of one side of the rhombus (the second incision is still made at a 60-degree angle to this first incision). The Webster flap is made similarly to the Dufourmentel flap, but the second incision is made at a 30-degree (rather than 60-degree) angle to the first incision, and the inferior corner includes an M-plasty. Both of these modifications allow for tension sharing between the primary and secondary defects.[16][17][18]

Bilobed Flap

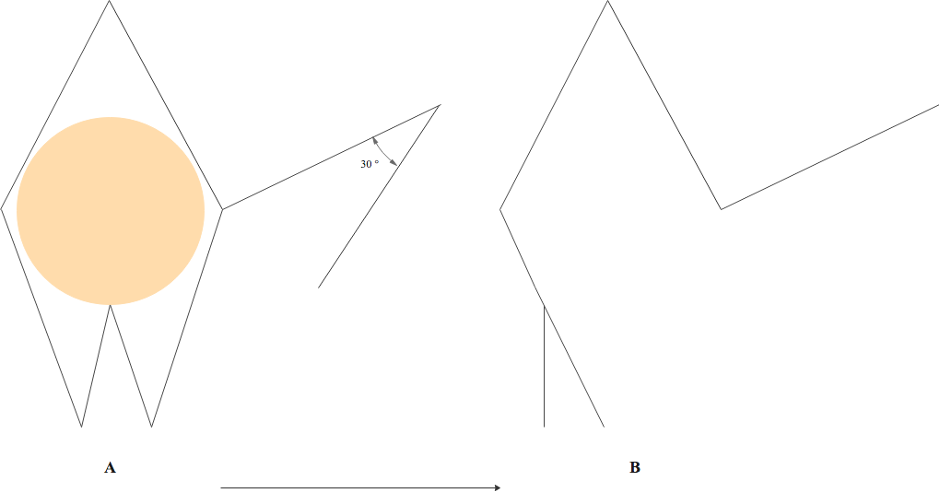

Esser originally described the bilobed flap in 1918, which was later modified in 1989 by Zitelli. This flap is particularly useful for repairing defects of the lower third of the nose, but it can also be used on other parts of the face, neck, helix and posterior ear, eyelids, feet, hands, and trunk. The bilobed flap consists of two lobes based on a single pedicle and has the advantage of recruiting more mobile tissue with more favorable tension vectors. Zitelli's modified bilobed flap uses 45-degree angles (rather than 90 degrees of Esser's design), minimizing standing cutaneous cone defects.

The bilobed flap is constructed based on a circular or oval defect. A pivot point is selected at least one radius away from the edge of the defect, and lines are drawn tangential to the edges of the circle to delineate the Burow's triangle that will be excised (to prevent dog-ear formation). The first or primary lobe is drawn at a 45-degree angle from the pivot point with a similar length and diameter to those of the defect (some will use a slightly smaller base or slightly longer flap); when the skin is not very elastic, such as on the tip of the nose, a lobe comparable in size to the defect should be designed, but when the skin is more elastic, the lobe may only need to cover 80% of the defect's surface area. The secondary lobe is then centered at a 90-degree angle from the pivot point (45 degrees from the center of the first lobe); it should be slightly longer than the first lobe yet narrower towards the base (approximate width of the half to a full diameter of the primary lobe), and be excised with a triangular tip to create a linear scar at the tertiary defect. The width of the secondary lobe is a balance between being small enough to allow easy closure of the tertiary defect and large enough to close the primary defect site with surrounding structural displacement.

The wide undermining of the flap and the peripheries of the donor and defect site should be performed after flap incision and excision of the defect's Burow's triangle. Hemostasis should be attained, and the flap should be lifted and rotated approximately 45 degrees so that the primary lobe fills the original defect and the secondary lobe fills the primary lobe donor site. The tertiary defect is closed first using deep dermal (4-0 or 5-0) sutures, followed by deep dermal suturing of the primary lobe into the defect. The secondary flap tip is then trimmed to precisely fit the remaining defect (primary lobe donor site) and sutured similarly. Superficial simple interrupted, vertical mattress or occasionally running/simple continuous (5-0 or 6-0) sutures are placed to reapproximate the superficial epidermal edges. The finished bilobed flap has a closure that resembles the shape of the top of a heart.

Variations of the classic Zitelli bilobed flap include the trilobed transposition flap. This flap is particularly useful with larger alar defects and/or rigid sebaceous nasal skin and aims to prevent the ipsilateral alar depression and contralateral alar elevation that can be seen after repair. It is designed similarly to the bilobed flap with approximately 45-degree angles between lobes but has three lobes rather than two. This can keep the tension vector perpendicular to the nasal ala and maintain alar symmetry.[19][20]

Nasolabial (Melolabial) Transposition Flap

Dieffenbach originally described the nasolabial flap in 1830 when he used superiorly-based nasolabial flaps to reconstruct the nasal ala. This technique was modified by Esser around 1920 when he used an inferiorly-based flap to close a palatal fistula and, in so doing, developed the foundation for the method used more commonly today. This flap is particularly useful for defects of the lateral and central ala. The nasolabial flap is harvested from the relatively sebaceous skin in the medial cheek, adjacent to the nasolabial fold, before being transposed in the alar defect, allowing the scar to hide well in the nasolabial fold at the boundary of the medial cheek and the cutaneous upper lip. Although historically a two-step surgical reconstruction, if planned and designed appropriately, the nasolabial flap can be employed as a single-stage repair.

The nasolabial flap is typically planned around a circular defect on the lateral or central nasal ala. Planning is started by designing the superior Burow's triangle above the primary defect, which should be relatively tall and narrow with no more than a 30-degree apical angle. The medial margin of the flap is drawn within the nasolabial fold, and the lateral margin is located on the medial cheek, extending superiorly only as high as the point over which the flap is to be transposed. It should be noted that the flap is planned longer than the primary defect (after the Burow's triangle is excised) to compensate for the contraction that will occur as the flap is lifted onto the nose. The base of the flap should be similar in width to the defect. After the excision of the Burow's triangle and incision of the flap, the wide undermining of the cheek at the donor site is needed to medially advance the cheek. Hemostasis should be attained. Most will place a tacking or anchoring suture from the dermal undersurface of the flap to the periosteum of the nasal bone or maxilla, in the concavity of the nasofacial sulcus, to minimize the tension of the flap on the alar defect when sutured into place and to minimize blunting of the nasofacial sulcus as well. The secondary defect is closed using deep dermal absorbable (4-0 or 5-0) sutures, and the flap transposed into the alar defect. The flap should be carefully trimmed to fit the defect; miscalculations can result in functional or aesthetic complications such as alar retraction and pincushioning. Epidermal edges are then approximated using simple, interrupted, or running/simple continuous nonabsorbable (5-0 or 6-0) suture.[21][22]

Z-Plasty

The first example of contemporary Z-plasty was reported by Berger in 1904. Improvements were made by Morestin in 1914, and the understanding of the flap's dynamics was expanded by Limberg shortly after. This transposition flap is used primarily to revise scars after cutaneous surgery. Indications for using z-plasty transpositions include improving scar cosmesis by changing the direction of the scar, particularly those crossing relaxed skin tension lines, and releasing scar contractures or webs by redistributing tension over the wound, which is important for scars that distort free margins or other cosmetically-sensitive features. The Z-plasty technique generally involves the creation of two flaps from three equal limbs and two same-degree angles, ultimately lengthening and rotating the scar.

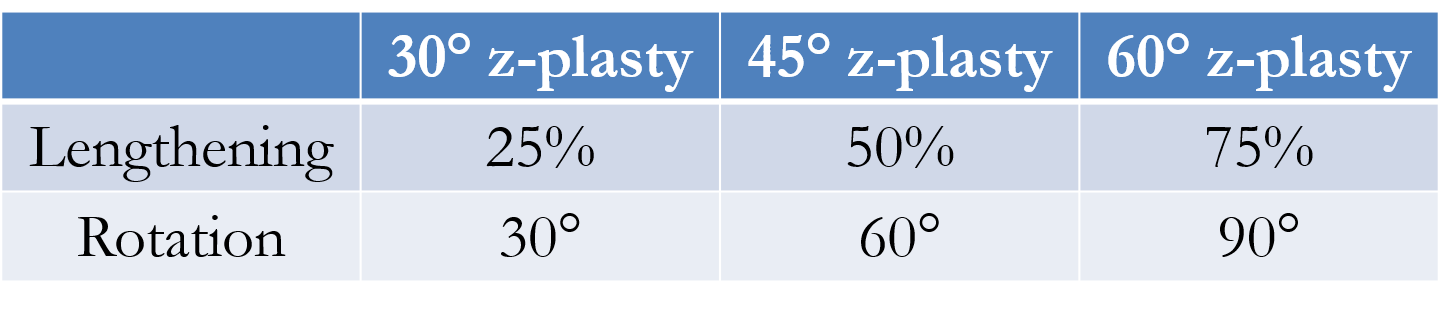

The first limb of the Z-plasty is drawn along the axis of the scar from one edge to the other. Typically, two equal-sized limbs are then drawn at identical angles on either end of the first limb, although the length and angles of the limbs do not necessarily have to be identical. The angles formed by the junction of the limbs should be between 30 and 75 degrees; an angle less than 30 degrees may cause tip necrosis, whereas an angle greater than 75 degrees creates flaps that are difficult to rotate, causing increased tension and larger standing cutaneous deformities. The angles also dictate the expected lengthening of the scar size: 30, 45, and 60 degrees result in a 25%, 50%, and 75% gain in tissue length, respectively, as well as rotation by 30, 60, and 90 degrees, respectively. After careful planning, an incision along or around the scar and the outlined limbs is made. Wide undermining should occur on both triangular flaps that are formed and the edges of the wound, followed by meticulous hemostasis. The tips of the flaps are then transposed. Deep dermal absorbable (4-0 or 5-0) sutures are placed starting with the lateral limbs, and the epidermal edges are approximated using simple, interrupted, or vertical mattress nonabsorbable (5-0 or 6-0) sutures.

Complications

The possible complications of these procedures include edema, pain, infection, flap necrosis, scarring, bleeding/hematoma, and hypertrophic scar or keloid. Fairly specific to transposition flaps is the trapdoor effect in which there is a "pincushion" appearance (elevation of part of the flap above surrounding skin). This phenomenon can be aggravated by insufficient tissue undermining, an oversized flap, excess subcutaneous fat in the flap, or insufficient flap contact with the wound base. Trapdoor deformities are more likely to occur when the flap is superiorly based, and the lymphatic drainage pathways are interrupted at the dependent aspect of the flap due to an incision.[11][23][24]

Clinical Significance

Transposition flaps represent a common method for repairing cutaneous surgical defects that may otherwise be functionally or aesthetically unacceptable if other reconstructive methods are selected.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team of an operative clinician and nurse assistant should perform the procedure for the best outcomes. A wound care nurse and clinician experienced in the follow-up of transposition flaps should monitor the patient for possible complications, including infections, necrosis, and poor perfusion. Coordination of care with open communication and meticulous record-keeping is crucial to the successful implementation of the interprofessional healthcare team model. [Level 5] Educating the patient on the importance of smoking cessation is vital.[25]