[1]

Chen Q, Gao H, Hua Z, Yang K, Yan J, Zhang H, Ma K, Zhang S, Qi L, Li S. Outcomes of Surgical Repair for Persistent Truncus Arteriosus from Neonates to Adults: A Single Center's Experience. PloS one. 2016:11(1):e0146800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146800. Epub 2016 Jan 11

[PubMed PMID: 26752522]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[2]

Puri K, Allen HD, Qureshi AM. Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatrics in review. 2017 Oct:38(10):471-486. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0032. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28972050]

[3]

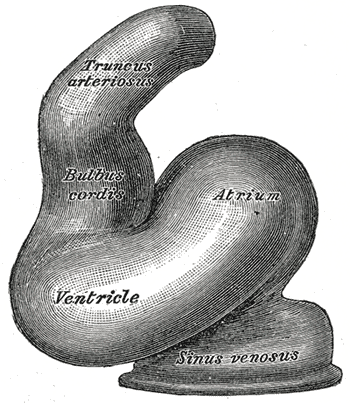

Moorman A, Webb S, Brown NA, Lamers W, Anderson RH. Development of the heart: (1) formation of the cardiac chambers and arterial trunks. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2003 Jul:89(7):806-14

[PubMed PMID: 12807866]

[4]

McElhinney DB, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, Goldmuntz E. Chromosome 22q11 deletion in patients with truncus arteriosus. Pediatric cardiology. 2003 Nov-Dec:24(6):569-73

[PubMed PMID: 12947506]

[5]

Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008 Dec:153(6):807-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.059. Epub 2008 Jul 26

[PubMed PMID: 18657826]

[6]

Lenox CC, Debich DE, Zuberbuhler JR. The role of coronary artery abnormalities in the prognosis of truncus arteriosus. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1992 Dec:104(6):1728-42

[PubMed PMID: 1453739]

[7]

Martin BJ, Karamlou TB, Tabbutt S. Shunt Lesions Part II: Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connections and Truncus Arteriosus. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2016 Aug:17(8 Suppl 1):S310-4. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000822. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27490615]

[8]

Konstantinov IE, Karamlou T, Blackstone EH, Mosca RS, Lofland GK, Caldarone CA, Williams WG, Mackie AS, McCrindle BW. Truncus arteriosus associated with interrupted aortic arch in 50 neonates: a Congenital Heart Surgeons Society study. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006 Jan:81(1):214-22

[PubMed PMID: 16368368]

[9]

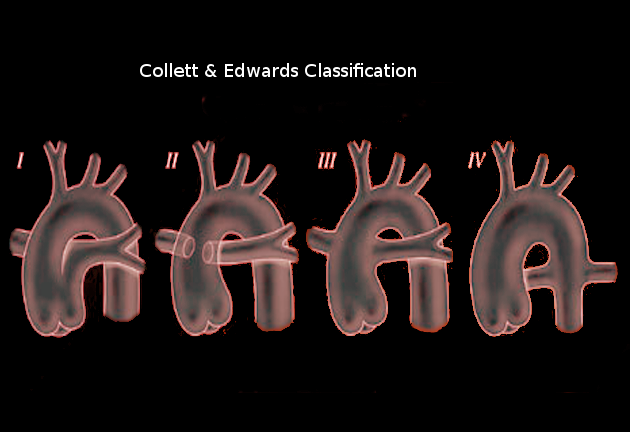

Butto F, Lucas RV Jr, Edwards JE. Persistent truncus arteriosus: pathologic anatomy in 54 cases. Pediatric cardiology. 1986:7(2):95-101

[PubMed PMID: 3797293]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[10]

Van Praagh R. Truncus arteriosus: what is it really and how should it be classified? European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1987:1(2):65-70

[PubMed PMID: 2856609]

[11]

Marcelletti C, McGoon DC, Mair DD. The natural history of truncus arteriosus. Circulation. 1976 Jul:54(1):108-11

[PubMed PMID: 1277412]

[12]

Niwa K, Perloff JK, Kaplan S, Child JS, Miner PD. Eisenmenger syndrome in adults: ventricular septal defect, truncus arteriosus, univentricular heart. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999 Jul:34(1):223-32

[PubMed PMID: 10400015]

[13]

Calder L, Van Praagh R, Van Praagh S, Sears WP, Corwin R, Levy A, Keith JD, Paul MH. Truncus arteriosus communis. Clinical, angiocardiographic, and pathologic findings in 100 patients. American heart journal. 1976 Jul:92(1):23-38

[PubMed PMID: 985630]

[14]

TAUSSIG HB. Clinical and pathological findings in cases of truncus arteriosus in infancy. The American journal of medicine. 1947 Jan:2(1):26-34

[PubMed PMID: 20278447]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[15]

TANDON R, HAUCK AJ, NADAS AS. PERSISTENT TRUNCUS ARTERIOSUS. A CLINICAL, HEMODYNAMIC, AND AUTOPSY STUDY OF NINETEEN CASES. Circulation. 1963 Dec:28():1050-60

[PubMed PMID: 14082918]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[16]

Tlaskal T, Hucin B, Kucera V, Vojtovic P, Gebauer R, Chaloupecky V, Skovranek J. Repair of persistent truncus arteriosus with interrupted aortic arch. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2005 Nov:28(5):736-41

[PubMed PMID: 16194613]

[17]

Chew C, Halliday JL, Riley MM, Penny DJ. Population-based study of antenatal detection of congenital heart disease by ultrasound examination. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007 Jun:29(6):619-24

[PubMed PMID: 17523161]

[18]

Mawad W, Mertens LL. Recent Advances and Trends in Pediatric Cardiac Imaging. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2018 Feb 21:20(1):9. doi: 10.1007/s11936-018-0599-x. Epub 2018 Feb 21

[PubMed PMID: 29468314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[19]

Samyn MM. A review of the complementary information available with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and multi-slice computed tomography (CT) during the study of congenital heart disease. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging. 2004 Dec:20(6):569-78

[PubMed PMID: 15856644]

[20]

Ricci Z, Haiberger R, Pezzella C, Garisto C, Favia I, Cogo P. Furosemide versus ethacrynic acid in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Critical care (London, England). 2015 Jan 7:19(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0724-5. Epub 2015 Jan 7

[PubMed PMID: 25563826]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[21]

Naimo PS, Fricke TA, Yong MS, d'Udekem Y, Kelly A, Radford DJ, Bullock A, Weintraub RG, Brizard CP, Konstantinov IE. Outcomes of Truncus Arteriosus Repair in Children: 35 Years of Experience From a Single Institution. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Summer:28(2):500-511. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2015.08.009. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28043468]

[22]

Sandrio S, Rüffer A, Purbojo A, Glöckler M, Dittrich S, Cesnjevar R. Common arterial trunk: current implementation of the primary and staged repair strategies. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2015 Dec:21(6):754-60. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv261. Epub 2015 Sep 10

[PubMed PMID: 26362626]

[23]

Huff C, Mastropietro CW, Riley C, Byrnes J, Kwiatkowski DM, Ellis M, Schuette J, Justice L. Comprehensive Management Considerations of Select Noncardiac Organ Systems in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. World journal for pediatric & congenital heart surgery. 2018 Nov:9(6):685-695. doi: 10.1177/2150135118779072. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30322370]

[24]

Gotsch F, Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Hassan S, Yeo L. Prenatal diagnosis of truncus arteriosus using multiplanar display in 4D ultrasonography. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2010 Apr:23(4):297-307. doi: 10.3109/14767050903108206. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19900032]

[25]

Kalavrouziotis G, Purohit M, Ciotti G, Corno AF, Pozzi M. Truncus arteriosus communis: early and midterm results of early primary repair. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006 Dec:82(6):2200-6

[PubMed PMID: 17126135]

[26]

Asagai S, Inai K, Shinohara T, Tomimatsu H, Ishii T, Sugiyama H, Park IS, Nagashima M, Nakanishi T. Long-term Outcomes after Truncus Arteriosus Repair: A Single-center Experience for More than 40 Years. Congenital heart disease. 2016 Dec:11(6):672-677. doi: 10.1111/chd.12359. Epub 2016 Apr 29

[PubMed PMID: 27126954]

[27]

Alfieris GM, Swartz MF. The Initial Glimpse at Long-term Outcomes Following the Repair of Truncus Arteriosus. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Summer:28(2):512-513. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2016.08.001. Epub 2016 Aug 11

[PubMed PMID: 28043469]

[28]

Graziani F, Delogu AB. Evaluation of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. World journal for pediatric & congenital heart surgery. 2016 Mar:7(2):185-91. doi: 10.1177/2150135115623285. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26957402]

[29]

Williams JM, de Leeuw M, Black MD, Freedom RM, Williams WG, McCrindle BW. Factors associated with outcomes of persistent truncus arteriosus. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999 Aug:34(2):545-53

[PubMed PMID: 10440171]

[30]

Gómez O, Soveral I, Bennasar M, Crispi F, Masoller N, Marimon E, Bartrons J, Gratacós E, Martinez JM. Accuracy of Fetal Echocardiography in the Differential Diagnosis between Truncus Arteriosus and Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2016:39(2):90-9. doi: 10.1159/000433430. Epub 2015 Jun 25

[PubMed PMID: 26113195]

[31]

Balachandran R, Nair SG, Kumar RK. Establishing a pediatric cardiac intensive care unit - Special considerations in a limited resources environment. Annals of pediatric cardiology. 2010 Jan:3(1):40-9. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.64374. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20814475]

[32]

Lantin-Hermoso MR, Berger S, Bhatt AB, Richerson JE, Morrow R, Freed MD, Beekman RH 3rd, SECTION ON CARDIOLOGY, CARDIAC SURGERY. The Care of Children With Congenital Heart Disease in Their Primary Medical Home. Pediatrics. 2017 Nov:140(5):. pii: e20172607. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2607. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29084831]

[33]

Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, Bozkurt B, Broberg CS, Colman JM, Crumb SR, Dearani JA, Fuller S, Gurvitz M, Khairy P, Landzberg MJ, Saidi A, Valente AM, Van Hare GF. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Apr 2:73(12):1494-1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1028. Epub 2018 Aug 16

[PubMed PMID: 30121240]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[34]

Yamagishi H. Clinical Developmental Cardiology for Understanding Etiology of Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Apr 24:11(9):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11092381. Epub 2022 Apr 24

[PubMed PMID: 35566507]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence