Continuing Education Activity

Tuberculosis (TB) is a human disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It mainly affects the lungs, making pulmonary disease the most common presentation. Other commonly affected organ systems include the respiratory system, the gastrointestinal (GI) system, the lymphoreticular system, the skin, the central nervous system, the musculoskeletal system, the reproductive system, and the liver. In the past few decades, there has been a concerted global effort to eradicate tuberculosis. Despite the gains in tuberculosis control and the decline in both new cases and mortality, it still accounts for a huge burden of morbidity and mortality worldwide. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of tuberculosis and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance outcomes for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the epidemiology of tuberculosis.

- Review the presentation of a patient with tuberculosis.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for tuberculosis.

- Employ interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with tuberculosis.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ancient human disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis which mainly affects the lungs, making pulmonary disease the most common presentation (K Zaman, 2010) [1]. However, TB is a multi-systemic disease with a protean presentation. The organ system most commonly affected includes the respiratory system, the gastrointestinal (GI) system, the lymphoreticular system, the skin, the central nervous system, the musculoskeletal system, the reproductive system, and the liver [2][3].

Evidence of TB has been reported in human remains dated thousands of years (Hershkovitz et al., 2017, K Zaman, 2010). For a human pathogen with no known environmental reservoir, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has honed the art of survival and has persisted in human communities from antiquity through modern times.

In the past few decades, there has been a concerted global effort to eradicate TB. These efforts had yielded some positive dividends, especially since 2000 when the World Health Organization (WHO, 2017) estimated that the global incidence rate for tuberculosis has fallen by 1.5% every year. Furthermore, mortality arising from tuberculosis has significantly and steadily declined. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2016) reports a 22% drop in global TB mortality from 2000 through 2015.

Despite the gains in tuberculosis control and the decline in both new cases and mortality, TB still accounts for a huge burden of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The bulk of the global burden of new infection and tuberculosis death is borne by developing countries, with 6 countries, India, Indonesia, China, Nigeria, Pakistan, and South Africa, accounting for 60% of TB death in 2015 (WHO, 2017).[4]

Tuberculosis remains a significant cause of both illness and death in developed countries, especially among individuals with a suppressed immune system[5][6]. People with HIV are particularly vulnerable to death due to tuberculosis. Tuberculosis accounted for 35% of global mortality in individuals with HIV/AIDS in 2015. (W.H.O, 2017). Children are also vulnerable, and tuberculosis was responsible for one million illnesses in children in 2015, according to the WHO.

Etiology

M. tuberculosis causes tuberculosis. M. tuberculosis is an alcohol and acid-fast bacillus. It is part of a group of organisms classified as the M. tuberculosis complex. Other members of this group are Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, and Mycobacterium microti[1]. Most other mycobacteria organisms are classified as non-tuberculous or atypical mycobacterial organisms.

M. tuberculosis is a non-spore-forming, non-motile, obligate-aerobic, facultative, catalase-negative, intracellular bacteria. The organism is neither gram-positive nor gram-negative because of a very poor reaction with the Gram stain. Weakly positive cells can sometimes be demonstrated on Gram stain, a phenomenon known as "ghost cells."

The organism has several unique features compared to other bacteria, such as the presence of several lipids in the cell wall, including mycolic acid, cord factor, and Wax-D. The high lipid content of the cell wall is thought to contribute to the following properties of M. tuberculosis infection:

- Resistance to several antibiotics

- Difficulty staining with Gram stain and several other stains

- Ability to survive under extreme conditions such as extreme acidity or alkalinity, low oxygen situation, and intracellular survival(within the macrophage)

The Ziehl-Neelsen stain is one of the most commonly used stains to diagnose T.B. The sample is initially stained with carbol fuchsin (pink color stain), decolorized with acid-alcohol, and then counter-stained with another stain (usually, blue-colored methylene blue). A positive sample would retain the pink color of the original carbol fuchsin, hence the designation, alcohol, and acid-fast bacillus (AAFB).

Epidemiology

Geographic Distribution

Tuberculosis is present globally[1]. However, developing countries account for a disproportionate share of tuberculosis disease burden. In addition to the six countries listed above, several countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Latin and Central America continue to have an unacceptably high burden of tuberculosis.

In more advanced countries, high-burden tuberculosis is seen among recent arrivals from tuberculosis-endemic zones, healthcare workers, and HIV-positive individuals. The use of immunosuppressive agents such as long-term corticosteroid therapy has also been associated with an increased risk.

More recently, the use of a monoclonal antibody targeting the inflammatory cytokine, tumor necrotic factor alpha (TNF-alpha), has been associated with an increased risk. Antagonists of this cytokine include several monoclonal antibodies (biologics) used for the treatment of inflammatory disorders. Drugs in this category include infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and golimumab. Patients using any of these medications should be monitored for tuberculosis before and during the period of drug treatment.

Other Major Risk Factors

- Socioeconomic factors: Poverty, malnutrition, wars

- Immunosuppression: HIV/AIDS, chronic immunosuppressive therapy (steroids, monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrotic factor), a poorly developed immune system (children, primary immunodeficiency disorders)

- Occupational: Mining, construction workers, pneumoconiosis (silicosis)

Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and Extremely Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB)

MDR-TB

- This refers to tuberculosis with strains of Mycobacterium which have developed resistance to the classic anti-tuberculosis medications. TB is especially a problem among patients with HIV/AIDS. Resistance to multiple anti-tuberculosis medications, including at least the two standard anti-tuberculous medications, Rifampicin or Isoniazid, is required to make a diagnosis of MDR-TB.

- Seventy-five percent of MDR-TB is considered primary MDR-TB, caused by infection with MDR-TB pathogens. The remaining 25% are acquired and occur when a patient develops resistance to treatment for tuberculosis. Inappropriate treatment for tuberculosis because of several factors such as antibiotic abuse; inadequate dosage; incomplete treatment, is the number one cause of acquired MDR-TB.

XDR-T.B

- This is a more severe type of MDR-TB. Diagnosis requires resistance to at least four anti-tuberculous medications, including resistance to Rifampicin, Isoniazid, and resistance to any two of the newer anti-tuberculous medications. The newer medications implicated in XDR-TB are the fluoroquinolones (Levofloxacin and moxifloxacin) and the injectable second-line aminoglycosides, Kanamycin, Capreomycin, and amikacin.

- The mechanism of developing XDR-TB is similar to the mechanism for developing MDR-TB.

- XDR -TB is an uncommon occurrence.

Pathophysiology

Although usually a lung infection, tuberculosis is a multi-system disease with protean manifestation. The principal mode of spread is through the inhalation of infected aerosolized droplets.

The body's ability to effectively limit or eliminate the infective inoculum is determined by the immune status of the individual, genetic factors, and whether it is a primary or secondary exposure to the organism. Additionally, M. tuberculosis possesses several virulence factors that make it difficult for alveolar macrophages to eliminate the organism from an infected individual. The virulence factors include the high mycolic acid content of the bacteria's outer capsule, which makes phagocytosis to be more difficult for alveolar macrophages. Furthermore, some of the other constituents of the cell wall, such as the cord factor, may directly damage alveolar macrophages. Several studies have shown that mycobacteria tuberculosis prevents the formation of an effective phagolysosome, hence, preventing or limiting the elimination of the organisms.

The first contact of the Mycobacterium organism with a host leads to manifestations known as primary tuberculosis. This primary TB is usually localized to the middle portion of the lungs, and this is known as the Ghon focus of primary TB. In most infected individuals, the Ghon focus enters a state of latency. This state is known as latent tuberculosis.

Latent tuberculosis is capable of being reactivated after immunosuppression in the host. A small proportion of people would develop an active disease following first exposure. Such cases are referred to as primary progressive tuberculosis. Primary progressive tuberculosis is seen in children, malnourished people, people with immunosuppression, and individuals on long-term steroid use.

Most people who develop tuberculosis do so after a long period of latency (usually several years after the initial primary infection). This is known as secondary tuberculosis. Secondary tuberculosis usually occurs because of the reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection. The lesions of secondary tuberculosis are in the lung apices. A smaller proportion of people who develop secondary tuberculosis do so after getting infected a second time (re-infection).

The lesions of secondary tuberculosis are similar for both reactivation and reinfection in terms of location (at the lung apices), and the presence of cavitation enables a distinction from primary progressive tuberculosis which tends to be in the middle lung zones and lacks marked tissue damage or cavitation.

Type-IV Hypersensitivity and Caseating Granuloma

Tuberculosis is a classic example of a cell-mediated delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.

Delayed Hypersensitivity Reaction: By stimulating the immune cells (the helper T-Lymphocyte, CD4+ cells), Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces the recruitment and activation of tissue macrophages. This process is enhanced and sustained by the production of cytokines, especially interferon-gamma.

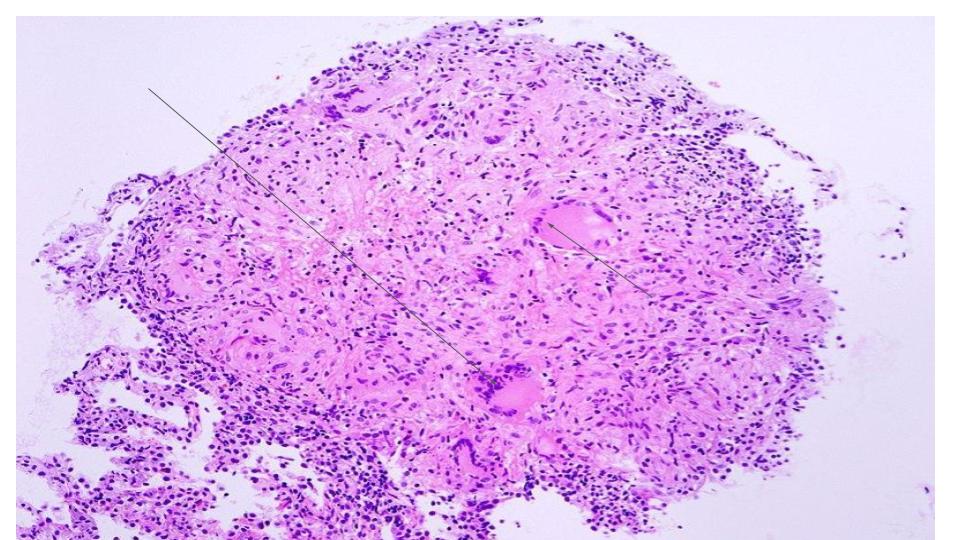

Two main changes involving macrophages occur during this process, namely, the formation of multinucleated giant cells and the formation of epithelioid cells. Giant cells are aggregates of macrophages that are fused together and function to optimize phagocytosis. The aggregation of giant cells surrounding the Mycobacterium particle and the surrounding lymphocytes and other cells is known as a granuloma.

Epithelioid cells are macrophages that have undergone a change in shape and have developed the ability for cytokine synthesis. Epithelioid cells are modified macrophages and have a flattened (spindle-like shape) as opposed to the globular shape characteristic of normal macrophages. Epithelioid cells often coalesce together to form giant cells in a tuberculoid granuloma.

In addition to interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma), the following cytokines play important roles in the formation of a tuberculosis granuloma, Interleukin-4 (IL-4), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrotic factor-alpha (TNF-alpha).

The appearance of the granuloma in tuberculosis has been described as caseous or cheese-like on gross examination. This is principally explained by the rich mycolic acid content of the mycobacterium cell wall. Because of this unique quality, the term caseous or caseating necrosis has been used to describe granulomatous necrosis caused by mycobacteria tuberculosis.

Histologically, caseous necrosis would present as a central area of uniform eosinophilia on routine hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Histopathology

The granuloma is the diagnostic histopathological hallmark of tuberculosis.

The defining features of the granuloma of tuberculosis are:

- Caseation or caseous necrosis is demonstrable as a region of central eosinophilia.

- Multinucleated giant cells

History and Physical

A chronic cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, low-grade fever, and night sweats are some of the most common physical findings in pulmonary tuberculosis.

Secondary tuberculosis differs in clinical presentation from primary progressive disease. In secondary disease, the tissue reaction and hypersensitivity are more severe, and patients usually form cavities in the upper portion of the lungs.

Pulmonary or systemic dissemination of the tubercles may be seen in active disease, and this may manifest as miliary tuberculosis characterized by millet-shaped lesions on chest x-ray. Disseminated tuberculosis may also be seen in the spine, the central nervous system, or the bowel.

Evaluation

Screening Tests

Tuberculin skin testing: Mantoux test (skin testing with PPD)

The Mantoux reaction following the injection of a dose of PPD (purified protein derivative) is the traditional screening test for exposure to Tuberculosis. The result is interpreted taking into consideration the patient's overall risk of exposure. Patients are classified into 3 groups based on the risk of exposure with three corresponding cut-off points. The 3 major groups used are discussed below.

Low Risk

- Individuals with minimal probability of exposure are considered to have a positive Mantoux test only if there is very significant induration following intradermal injection of PPD. The cut-off point for this group of people (with minimal risk of exposure) is taken to be 15 mm.

Intermediate Risk

- Individuals with intermediate probability are considered positive if the induration is greater than 10 mm.

High Risk

- Individuals with a high risk of a probability of exposure are considered positive if the induration is greater than 5 mm.

Examples of Patients in the Different Risk Categories

- Low Risk/Low Probability: Patients with no known risk of exposure to TB. Example: No history of travel, military service, HIV-negative, no contact with a chronic cough patient, no occupational exposure, no history of steroids. Not a resident of a TB-endemic region.

- Intermediate Risk/Probability: Residents of TB-endemic countries (Latin America, Sub -Sahara Africa, Asia), workers or residents of shelters, Medical or microbiology department personnel.

- High Risk/Probability: HIV-positive patient, a patient with evidence of the previous TB such as the healed scar on an x-ray), contact with chronic cough patients.

Note that a Mantoux test indicates exposure or latent tuberculosis. However, this test lacks specificity, and patients would require subsequent visits for interpreting the results as well as chest x-ray for confirmation. Although relatively sensitive, the Mantoux reaction is not very specific and may give false-positive reactions in individuals who have been exposed to the BCG vaccine.

Interferon release assays (IGRA, Quantiferon Assays)

This is a tuberculosis screening test that is more specific and equally as sensitive as the Mantoux test. This test assays for the level of the inflammatory cytokine, especially interferon-gamma.

The advantages of antigen-specific stimulation of IFN-γ release, especially in those with prior vaccination with BCG vaccine, include the test requires a single blood draw, obviating the need for repeat visits to interpret results. Furthermore, additional investigations, such as HIV screening, could be performed (after patient consent) on the same blood draw.

Quantiferon's disadvantages include cost and the technical expertise required to perform the test.

Screening in Immunocompromised Patients

Immunocompromised patients may show lower levels of reaction to PPD or false-negative Mantoux because of cutaneous anergy.

A high level of suspicion should be entertained when reviewing negative screening tests for tuberculosis in HIV-positive individuals.

The Significance of Screening

A positive screening test indicates exposure to tuberculosis and a high chance of developing active tuberculosis in the future. Tuberculosis incidence in patients with positive Mantoux test averages between 2% to 10% without treatment.

Patients with a positive test should have a chest x-ray as a minimum diagnostic test. In some cases, these patients should have additional tests. Patients meeting the criteria for latent tuberculosis should receive prophylaxis with isoniazid.

Screening Questionnaires for Resource-Poor Settings

Several screening questionnaires have been validated to enable healthcare workers working in remote and resource-poor environments to screen for tuberculosis.

These questionnaires make use of an algorithm that combines several clinical signs and symptoms of tuberculosis. Some of the commonly used symptoms are:

- Chronic cough

- Weight loss

- Fever and night sweats

- History of contact

- HIV status

- Blood in sputum

Several studies have confirmed the utility of using several criteria rather than a focus on only chronic cough or weight loss.

Confirmatory and Diagnostic Tests

- A chest x-ray is indicated to rule out or rule in the presence of active disease in all screening test-positive cases.

- Acid Fast Staining-Ziehl-Neelsen

- Culture

- Nuclear Amplification and Gene-Based Tests: These represent a new generation of diagnostic tools for tuberculosis. These tests enable the identification of bacteria or bacteria particles by making use of DNA-based molecular techniques.

The new molecular-based techniques are faster and enable rapid diagnosis with high precision. Confirmation of TB could be made in hours rather than the days or weeks it takes to wait for a standard culture. This is very important, especially among immunocompromised hosts where there is a high rate of false-negative results. Some molecular-based tests also allow for the identification of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

Treatment / Management

Latent Tuberculosis

2020 LTBI treatment guidelines include the NTCA- and CDC-recommended treatment regimens that comprise three preferred rifamycin-based regimens and two alternative monotherapy regimens with daily isoniazid. These are only recommended for persons infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is presumed to be susceptible to isoniazid or rifampin. A regimen of 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid plus rifapentine is a preferred regimen that is strongly recommended for children aged more than 2 years and adults. Another option is 4 months of daily rifampin for HIV-negative adults and children of all ages. Three months of daily isoniazid plus rifampin is a preferred treatment that is conditionally recommended for adults and children of all ages and for patients with HIV. Regimens of 6 or 9 months of daily isoniazid are alternative recommended regimens.

Treatment of Active Infection

Treatment of confirmed TB requires a combination of drugs. Combination therapy is always indicated, and monotherapy should never be used for tuberculosis. The most common regimen for TB includes the following anti-TB medications:

First-Line Medications, Group 1

- Isoniazid - Adults (maximum): 5 mg/kg (300 mg) daily; 15 mg/kg (900 mg) once, twice, or three times weekly.Children (maximum): 10-15 mg/kg (300 mg) daily; 20--30 mg/kg (900 mg) twice weekly (3).Preparations. Tablets (50 mg, 100 mg, 300 mg); syrup (50 mg/5 ml); aqueous solution (100 mg/ml) for IV or IM injection.

- Rifampicin - Adults (maximum): 10 mg/kg (600 mg) once daily, twice weekly, or three times weekly.Children (maximum): 10-20 mg/kg (600 mg) once daily or twice weekly.Preparations. Capsules (150 mg, 300 mg)

- Rifabutin- Adults (maximum): 5 mg/kg (300 mg) daily, twice, or three times weekly. When rifabutin is used with efavirenz the dose of rifabutin should be increased to 450--600 mg either daily or intermittently.Children (maximum): Appropriate dosing for children is unknown. Preparations: Capsules (150 mg) for oral administration.

- RIfapentine - Adults (maximum): 10 mg/kg (600 mg), once weekly (continuation phase of treatment)Children: The drug is not approved for use in children.Preparation. Tablet (150 mg, film-coated).

- Pyrazinamide - Adults: 20-25 mg/kg per day. Children (maximum): 15-30 mg/kg (2.0 g) daily; 50 mg/kg twice weekly (2.0 g).Preparations. Tablets (500 mg).

- Ethambutol - Adults: 15-20 mg/kg per day: Children (maximum): 15-20 mg/kg per day (2.5 g); 50 mg/kg twice weekly (2.5 g). The drug can be used safely in older children but should be used with caution in children in whom visual acuity cannot be monitored (generally less than 5 years of age) (66). In younger children, EMB can be used if there is a concern with resistance to INH or RIF.Preparations. Tablets (100 mg, 400 mg) for oral administration.

Isoniazid and Rifampicin follow a 4-drug regimen (usually including Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Ethambutol, and Pyrazinamide) for 2 months or six months. Vitamin B6 is always given with Isoniazid to prevent neural damage (neuropathies).

Several other antimicrobials are effective against tuberculosis, including the following categories:

Second-Line Anti-tuberculosis Drugs, Group 2

Injectable aminoglycosides and injectable polypeptides

Injectable aminoglycosides

- Amikacin

- Kanamycin

- Streptomycin

Injectable polypeptides

Second-Line Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs, Group 3, Oral and Injectable Fluoroquinolones

Fluoroquinolones

- Levofloxacin

- Moxifloxacin

- Ofloxacin

- Gatifloxacin

Second-Line Anti-tuberculosis Drugs, Group 4

- Para-aminosalicylic acid

- Cycloserine

- Terizidone

- Ethionamide

- Prothionamide

- Thioacetazone

- Linezolid

Third-Line Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs, Group 5

These are medications with variable but unproven efficacy against TB. They are used for total drug-resistant TB as drugs of last resort.

- Clofazimine

- Linezolid

- Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid

- Imipenem/cilastatin

- Clarithromycin

MDR-TB, XDR-TB

Multi-drug-resistant TB is becoming increasingly common.

The combination of first-line and second-line medications is used at high doses to treat this condition.

Bedaquiline

On December 28, 2012, the United States Food and Drug Administration Agency (FDA) approved Bedaquiline as a drug for treating MDR-TB. This is the first FDA approval for an anti-TB medication in 40 years. While showing remarkable promise in drug-resistant tuberculosis, cost remains a big obstacle to delivering this drug to the people most affected by MDR-TB.

Clinical and Laboratory Monitoring

Liver function tests are required for all patients taking isoniazid. Other monitoring in TB includes monitoring for retinopathies for patients on ethambutol.

Treatment of Patients with HIV

In patients with active TB and HIV with severe immunosuppression (CD4+ 60/microliter), the recommendations are to immediately start antituberculous therapy, followed by the initiation of anti-retroviral after 2 to 4 weeks. Delaying treatment with antiretroviral drugs prevents the development of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). This is a syndrome characterized by paradoxical worsening of symptoms of primary disease when treatment with antiretroviral agents is initiated. The presenting infection should be treated immediately, and retroviral should start no earlier than 2 weeks. The earlier the antiretroviral agents are initiated, the greater the likelihood of IRIS. Unnecessary delay of antiretroviral therapy leads to an increased risk of death from AIDS.

Differential Diagnosis

Tuberculosis is a great mimic and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of several systemic disorders. The following is a non-exhaustive list of conditions to be strongly considered when evaluating the possibility of pulmonary tuberculosis.

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Non-tuberculous mycobacterium

- Fungal infection

- Histoplasmosis

- Sarcoidosis

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Side Effect associated with most commonly used anti-TB drugs [7]

1) Isoniazid- Asymptomatic elevation of aminotransferases (10-20%), clinical hepatitis (0.6%), peripheral neurotoxicity, hypersensitivity.[8]

2) Rifampin- Pruritis, nausea & vomiting, flulike symptoms, hepatotoxicity, orange discoloration of bodily fluid.

3) Rifabutin- Neutropenia, uveitis (0.01%), polyarthralgias, hepatotoxicity (1%))

4) Rifapentine- Similar to rifampin

5) Pyrazinamide- Hepatotoxicity (1%), nausea & vomiting, polyarthralgias (40%), acute gouty arthritis, rash, and photosensitive dermatitis

6) Ethambutol- Retrobulbar neuritis (18%)

One of the most important aspects of tuberculosis treatment is close follow-up and monitoring for these side effects. Most of these side effects can be managed by either close monitoring or adjusting the dose. In some cases, the medication needs to be discontinued, and second-line therapy should be considered if other alternatives are not available.

Prognosis

The majority of patients with a diagnosis of TB have a good outcome. This is mainly because of effective treatment. Without treatment mortality rate for tuberculosis is more than 50%.

The following group of patients is more susceptible to worse outcomes or death following TB infection:

- Extremes of age, elderly, infants, and young children

- Delay in receiving treatment

- Radiologic evidence of extensive spread.

- Severe respiratory compromise requiring mechanical ventilation

- Immunosuppression

- Multidrug resistance (MDR) tuberculosis

Complications

Most patients have a relatively benign course. Complications are more frequently seen in patients with the risk factors mentioned above. Some of the complications associated with tuberculosis are:

- Extensive lung destruction

- Damage to cervical sympathetic ganglia leading to Horner's syndrome.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Milliary spread (disseminated tuberculosis), including TB meningitis.

- Empyema

- Pneumothorax

- Systemic amyloidosis

Pearls and Other Issues

Tuberculosis is a preventable and treatable infectious disease. Having said that, it is still one of the major contributors to morbidity and mortality in developing countries where we are still struggling to provide adequate access to care. Other challenges include lack of awareness, delayed diagnosis, poor accessibility to medication and vaccination as well as medication adherence. DOTS (Direct Observed Therapy), proposed by WHO, has been very effective in recent years to improve adherence to treatment in tuberculosis patients. [9][10] Also, vaccination drive in developing countries has played a bigger role in decreasing the prevalence of this infection. The preventive effect of BCG vaccination is controversial, but many studies have identified vaccination as a very important tool in the fight against tuberculosis, and we need to keep our focus on childhood vaccination, especially in developing countries.[11] WHO and other health organizations have to continue their investment in developing strategies and research until we eradicate this disease from the world map. New antituberculosis drugs need to be developed to shorten or otherwise simplify the treatment of tuberculosis caused by drug-susceptible organisms, to improve the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis, and to provide more efficient and effective treatment of latent tuberculosis infection.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A team approach involving nurses, clinicians, and technicians will lead to the best outcomes in treating patients with tuberculosis. [Level 5]