Continuing Education Activity

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is a common condition that typically involves lower extremity edema, trophic skin changes, and discomfort secondary to venous hypertension. Disability related to chronic venous insufficiency can contribute to a significantly diminished quality of life and a loss of productivity. In most cases, this condition is caused by the incompetence of the valvular action of venous walls. This activity describes the pathophysiology, etiology, and presentation of chronic venous insufficiency and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of chronic venous insufficiency.

- Summarize the typical presentation of chronic venous insufficiency.

- Outline the treatment options available for chronic venous insufficiency.

- Explain some interprofessional team strategies to improve care and optimize outcomes for patients affected by chronic venous insufficiency.

Introduction

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) typically refers to lower extremity edema, skin trophic changes, and discomfort secondary to venous hypertension. Chronic venous insufficiency is a prevalent disease process. Disability related to chronic venous insufficiency contributes to a diminished quality of life and loss of work productivity. In most cases, the cause is incompetent valves. Each year approximately 150,000 new patients are diagnosed with chronic venous insufficiency, and nearly $500 million is used in the care of these patients.

If CVI is left untreated, it is usually progressive and leads to post-phlebitic syndrome and venous ulcers. Besides the cosmetic deficit, the patient may complain of pain, leg swelling, pruritus, and skin discoloration. The cornerstone of treatment is the use of compression stockings, but compliance rates are poor. Many patients elect to undergo surgery, and the outcomes do vary.

The CEAP classification (clinical, etiology, anatomy, and pathophysiology) has been developed to guide decision-making in chronic venous insufficiency evaluation and treatment. The system has been shown to predict the patient's quality of life and the severity of their symptoms.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The etiology of chronic venous insufficiency can also be classified as either primary or secondary to deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

Primary chronic venous insufficiency refers to the symptomatic presentation without a precipitating event and is due to congenital defects or changes in venous wall biochemistry. Recent studies suggest that approximately 70% of patients have primary chronic venous insufficiency, and 30% have secondary disease. Studies into primary chronic venous insufficiency have identified reduced elastin content, increased extracellular matrix remodeling, and inflammatory infiltrate. The culmination of which alters the integrity of the vein, promoting dilation and valvular incompetence.

Secondary chronic venous insufficiency occurs in response to a DVT, which triggers an inflammatory response, subsequently injuring the vein wall. Irrespective of the specific etiology, chronic venous insufficiency promotes venous hypertension. The most common non-modifiable risk factors are female gender and non-thrombotic iliac vein obstruction (May-Thurner syndrome). Several studies have also suggested a genetic component contributing to vein wall laxity. Modifiable risk factors include smoking, obesity, pregnancy, prolonged standing, DVT, and venous injury.[4][5]

Epidemiology

An estimated six to seven million people in the United States have an existing diagnosis of advanced venous disease and meet diagnostic criteria for chronic venous insufficiency. Results across studies suggest that in the general population, between 1 and 17% of men and 1 and 40% of women may experience chronic venous insufficiency. Despite this wide range, non-western countries appear to have a lower overall prevalence. Among all chronic venous insufficiency patients, approximately 1% to 2.7% will develop a venous stasis ulcer. Formation of an ulcer carries a poor prognosis, with 40% of patients developing recurrence despite standard treatment. Management of chronic venous insufficiency accounts for approximately 2% of the United States' total healthcare.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Chronic venous insufficiency pathophysiology is either due to reflux (backward flow) or obstruction of venous blood flow. Chronic venous insufficiency can develop from the protracted valvular incompetence of superficial veins, deep veins, or perforating veins that connect them. In all cases, the result is venous hypertension of the lower extremities.

Superficial incompetence is usually due to weakened or abnormally shaped valves or widened venous diameters, which prevents normal valve congruence. The leaky valve, in most cases, is located near the termination of the greater saphenous vein into the common femoral vein. While in some cases, the valve dysfunction may be congenital, it can also be a result of trauma, prolonged standing, hormonal changes, or thrombosis.

Deep vein dysfunction is usually owing to the previous DVT, which results in inflammation, valve scarring and adhesion, and luminal narrowing. Perforating vein valvular failure allows higher pressure to enter the superficial venous system. The subsequent dilation prevents the proper closure of the valve cusps in the superficial veins. Most patients will also have the disease in the superficial veins. The resting venous pressure is a summation of the outflow obstruction, capillary inflow, valve function, and muscle pump function.

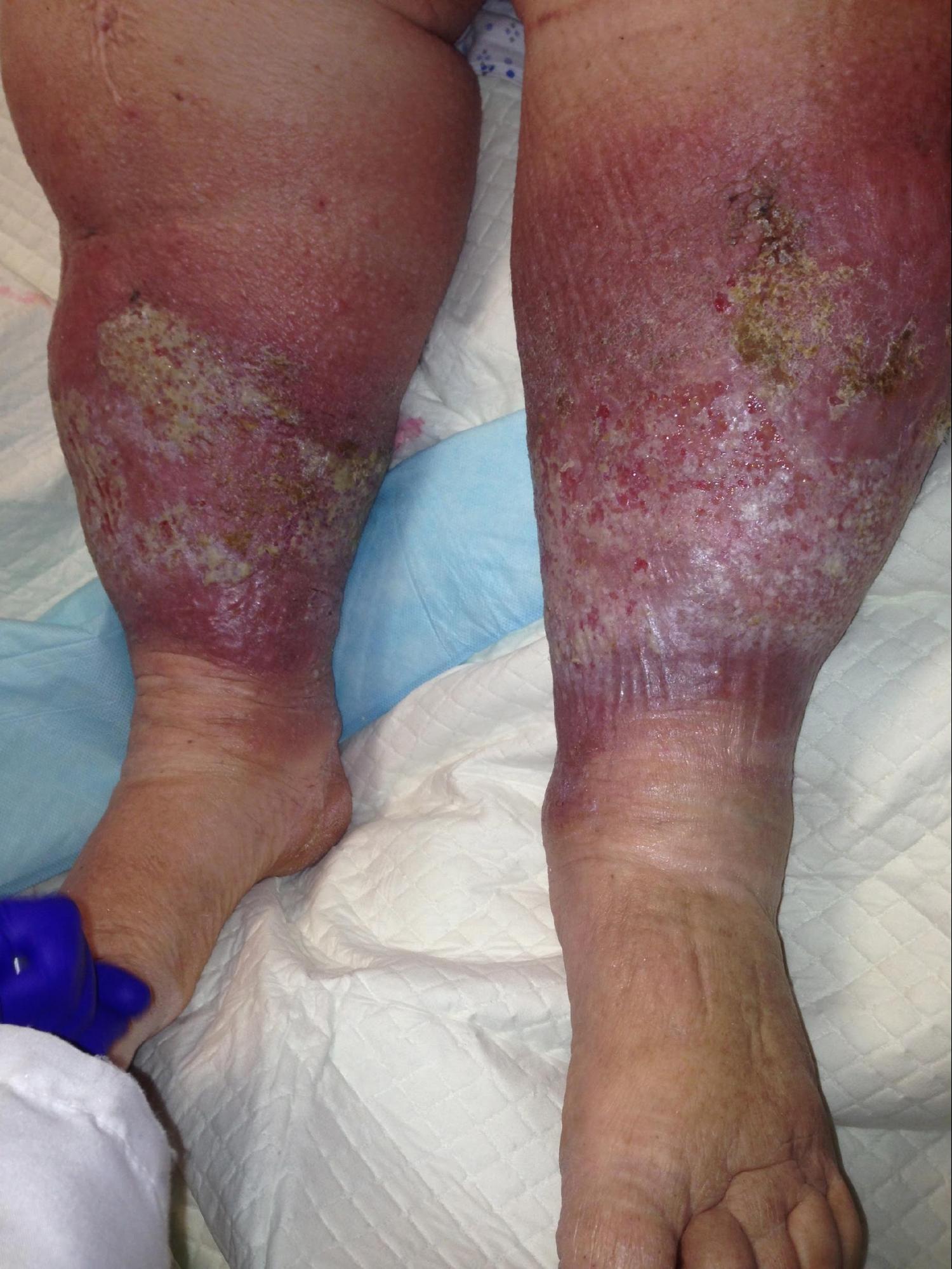

Regardless of the cause, the persistently elevated venous hydrostatic pressure may result in lower extremity pain, edema, and venous microangiopathy. Some patients develop permanent skin hyperpigmentation from hemosiderin deposition as red blood cells extravasate into the surrounding tissue. Many of these patients will also have lipodermatosclerosis, which is skin thickening from fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. As the disease progresses, the perturbed microcirculation and dermal weakening can result in ulcer formation.[8]

Risk factors for CVI

- Advanced age

- History of deep vein thrombosis

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Use of oral contraceptives

- Leg injury

- Hypertension

History and Physical

Patients with chronic venous insufficiency commonly present initially with a combination of dependent pitting edema, leg discomfort, fatigue, and itching. Although there can be variations in presentation among patients, certain features are more prevalent: pain, cramping, itching, prickling, and throbbing sensation. Patients may describe symptoms that improve with rest and leg elevation and with no association with exercise. This latter feature can be used to distinguish venous from arterial claudication. As their disease progresses, the presence of varicose veins and tenderness can be noted, along with refractory edema and skin changes. Patients with advanced disease will present with a severe blanched skin lesion, dermal atrophy, hyperpigmentation, dilated venous capillaries, and ulcer formation, most commonly overlying the medial malleolus.

A thorough history should note any hypercoagulable condition, oral contraceptive use, previous DVT or intervention, level of physical activity, and occupation. The patient’s presentation should carefully be distinguished from other pathologies with similar symptoms: diabetic ulcers, ischemic ulcers, and dermatologic conditions, including cancer.

The physical exam must involve a detailed assessment of any ulcers, distal pulses, and neuropathy. The Trendelenburg test may help differentiate between CVI caused by the superficial vein valves versus the deep system. To perform the test, the patient's leg is elevated, and all the venous blood is emptied. The surgeon then compresses the groin firmly to occlude the greater saphenous vein junction and asks the patient to stand up. If the leg does not fill up with venous blood, this indicates that incompetent valves in the superficial veins are the cause of CVI. if the leg does fill up with venous blood, then the valves that connect the superficial veins to the deep veins are incompetent. If the deep system valves are involved, the treatment is limited to compression stockings.

Evaluation

In addition to a full history and physical exam, the initial evaluation should include objective stratification. Venous reflux testing can identify regions affected and give some indication of the etiology and pathophysiology. Duplex ultrasonography, particularly B-mode imaging, can be helpful for identifying the regions of the affected anatomy. Insufficiency within a venous segment is defined as reflux of more than 0.5 seconds with distal compression. Invasive venography can be used in patients who may require surgery or have suspicion for venous stenosis. Other modalities that may be employed are an ankle-brachial index to exclude arterial pathology, air or photoplethysmography, intravascular ultrasound, and ambulatory venous pressures, which provide a global assessment of venous competence.[9][10]

Direct venography is no longer done because of improvements in ultrasound technology and the availability of MRI. Venous plethysmography can assess for reflux and muscle pump dysfunction, but the test is laborious and rarely done.

The venous filling time after the patient is asked to stand up from a seated position also is used to assess for CVI. Rapid filling of the legs in less than 20 seconds is abnormal.

Treatment / Management

Patients with chronic venous insufficiency should be treated based on the severity and nature of the disease. The treatment goals include reducing discomfort and edema, stabilizing skin appearance, removing painful varicose veins, and healing ulcers. Most patients should initially be treated conservatively with leg elevation, exercise (which improves calf muscle pump), weight management, and compression therapy. Compression therapy is long-term and only benefits patients who remain compliant.

If the superficial saphenous vein is involved, then there are several types of surgical procedures to manage CVI. If the deep venous system is involved, then the treatment is compression stockings.

Ulcers are treated best with compression bandaging systems. Chronic venous ulcerations entail a risk of infection and cancerous transformation (Marjolin ulcer). Compression therapy should be used with caution in patients with coexisting peripheral arterial disease. Significant arterial insufficiency should be treated before instituting a compression regimen. Patients whose ulcers fail to respond to compression may ultimately need surgical intervention. It is important to understand that sclerosants are used to manage spider veins and not varicose veins. The amount of solution required to collapse a varicosity would be huge and lead to extreme pain, thrombosis, and permanent skin discoloration.

Superficial vein reflux can be managed with foam sclerotherapy, endovenous thermal ablation, or stripping. Deep vein reflux may be treated with valve reconstruction or valve transplant. Perforator reflux can either be managed with sclerotherapy, endovenous thermal ablation, or with subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery (SEPS). It should be noted, however, that compression therapy regimens that are adhered to are highly effective in treating all forms of venous pathophysiology.[3][11][12]

As far as surgery is concerned, recurrences are common with all procedures. In addition, premature removal of a mildly affected saphenous vein also removes an important source of conduit if a bypass is needed in the future. Valvuloplasty is done in some centers, but the surgery is technically demanding and does not always work. Complications related to surgery include:

- Infection

- Injury to the arterial system

- Nerve injury (saphenous and or sural nerves)

- Poor cosmesis

- Scarring

No matter which surgery is selected, patients should combine it with compression stockings for maximal effectiveness.

Differential Diagnosis

- Lymphedema

- Cellulitis

- Stasis dermatitis

- Varicose veins

Staging

The CEAP classification for CVI is as follows:

- C0: no obvious feature of venous disease

- C1: the presence of reticular or spider veins

- C2: Obvious varicose veins

- C3: Presence of edema but no skin changes

- C4: skin discoloration, pigmentation

- C5: Ulcer that has healed

- C6: Acute ulcer

Etiology

- Primary

- Secondary (trauma, birth control pill)

- Congenital (Klipper Trenaunay)

- No cause is known

Anatomic

- Superficial deep

- Perforator

- No obvious anatomic location

Pathophysiology

- Obstruction, thrombosis

- Reflux

- Obstruction and reflux

- No venous pathology

Prognosis

CVI is not a benign disorder and carries enormous morbidity. Without correction, the condition is progressive. Venous ulcers are common and very difficult to treat. Chronic venous ulcers are painful and debilitating. Even with treatment, recurrences are common if venous hypertension persists. Nearly 60% develop phlebitis, which often progresses to deep vein thrombosis in more than 50% of patients. The venous insufficiency can also lead to severe hemorrhage. Surgery for CVI remains unsatisfactory despite the availability of numerous procedures. The cost of care to the patient is enormous.

Complications

- Venous ulcer

- Leg discoloration

- Thrombophlebitis

- DVT

- Pulmonary embolism

- Bleeding

- Secondary lymphedema

- Chronic pain

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients should be encouraged to exercise and avoid a sedentary lifestyle.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CVI is best managed by a team of healthcare professionals that includes a wound care nurse, vascular surgeon, general surgeon, bariatric nurse, and physical therapist. Most cases of CVI can be treated, but the key is compliance with treatment. Patients should be encouraged to wear compression stockings unless there is a contraindication. Just the use of stockings alone can markedly improve the symptoms and appearance. In addition, the patient should be encouraged to lose weight and avoid standing in one position for prolonged times. There are many surgical procedures to manage CVI, but none is 100% effective, and recurrences are common with all of them. The patient needs to be educated about compression stockings which are effective in the majority of patients. If the patient has a venous ulcer, long-term therapy is required. Until the venous hypertension is controlled, the chances of the ulcer healing are slim. The patient should be urged to exercise and avoid a sedentary lifestyle. Close communication between the team is important to improve patient outcomes. [13][14] [Level 5]

Outcomes

CVI, if left untreated, leads to very high morbidity and disability. Without treatment, the condition is progressive, ultimately leading to skin breakdown and ulcer formation. And these ulcers are difficult to heal, leading to significant pain and increased costs of healthcare. Many patients end up in wound clinics where they are treated for months and years without any significant benefit. These patients are also at an increased risk for deep vein thrombus and pulmonary embolism. In addition, any minor trauma is associated with torrential bleeding that can sometimes be fatal. [15][16](Level V)