[1]

Chen LH, Kozarsky PE, Visser LG. What's Old Is New Again: The Re-emergence of Yellow Fever in Brazil and Vaccine Shortages. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2019 May 2:68(10):1761-1762. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy777. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30204852]

[2]

Sanna A, Andrieu A, Carvalho L, Mayence C, Tabard P, Hachouf M, Cazaux CM, Enfissi A, Rousset D, Kallel H. Yellow fever cases in French Guiana, evidence of an active circulation in the Guiana Shield, 2017 and 2018. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2018 Sep:23(36):. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.36.1800471. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30205871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Leong WY. New diagnostic tools for yellow fever. Journal of travel medicine. 2018 Jan 1:25(1):. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay079. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30184173]

[4]

Javelle E, Gautret P, Raoult D. Towards the risk of yellow fever transmission in Europe. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2019 Jan:25(1):10-12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.08.015. Epub 2018 Aug 28

[PubMed PMID: 30170135]

[5]

Kaul RB, Evans MV, Murdock CC, Drake JM. Spatio-temporal spillover risk of yellow fever in Brazil. Parasites & vectors. 2018 Aug 29:11(1):488. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3063-6. Epub 2018 Aug 29

[PubMed PMID: 30157908]

[6]

Chippaux JP, Chippaux A. Yellow fever in Africa and the Americas: a historical and epidemiological perspective. The journal of venomous animals and toxins including tropical diseases. 2018:24():20. doi: 10.1186/s40409-018-0162-y. Epub 2018 Aug 25

[PubMed PMID: 30158957]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[7]

Barrett ADT. The reemergence of yellow fever. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Aug 31:361(6405):847-848. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8225. Epub 2018 Aug 23

[PubMed PMID: 30139914]

[8]

Faria NR, Kraemer MUG, Hill SC, Goes de Jesus J, Aguiar RS, Iani FCM, Xavier J, Quick J, du Plessis L, Dellicour S, Thézé J, Carvalho RDO, Baele G, Wu CH, Silveira PP, Arruda MB, Pereira MA, Pereira GC, Lourenço J, Obolski U, Abade L, Vasylyeva TI, Giovanetti M, Yi D, Weiss DJ, Wint GRW, Shearer FM, Funk S, Nikolay B, Fonseca V, Adelino TER, Oliveira MAA, Silva MVF, Sacchetto L, Figueiredo PO, Rezende IM, Mello EM, Said RFC, Santos DA, Ferraz ML, Brito MG, Santana LF, Menezes MT, Brindeiro RM, Tanuri A, Dos Santos FCP, Cunha MS, Nogueira JS, Rocco IM, da Costa AC, Komninakis SCV, Azevedo V, Chieppe AO, Araujo ESM, Mendonça MCL, Dos Santos CC, Dos Santos CD, Mares-Guia AM, Nogueira RMR, Sequeira PC, Abreu RG, Garcia MHO, Abreu AL, Okumoto O, Kroon EG, de Albuquerque CFC, Lewandowski K, Pullan ST, Carroll M, de Oliveira T, Sabino EC, Souza RP, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Trindade GS, Drumond BP, Filippis AMB, Loman NJ, Cauchemez S, Alcantara LCJ, Pybus OG. Genomic and epidemiological monitoring of yellow fever virus transmission potential. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Aug 31:361(6405):894-899. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7115. Epub 2018 Aug 23

[PubMed PMID: 30139911]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[9]

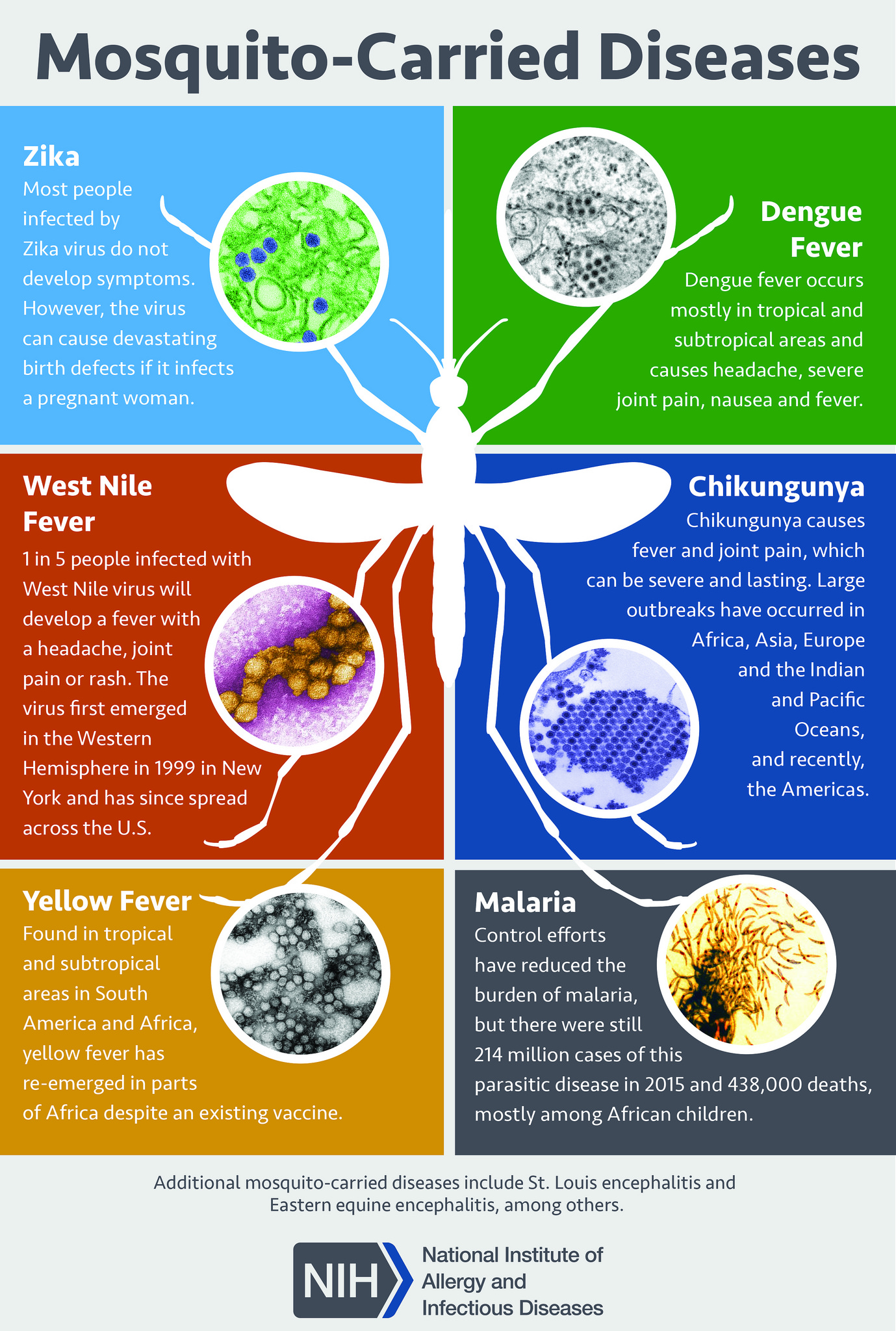

Lee H, Halverson S, Ezinwa N. Mosquito-Borne Diseases. Primary care. 2018 Sep:45(3):393-407. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.05.001. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30115330]

[10]

Callender DM. Management and control of yellow fever virus: Brazilian outbreak January-April, 2018. Global public health. 2019 Mar:14(3):445-455. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1512144. Epub 2018 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 30122143]

[11]

Peyraud N, Quéré M, Duc G, Chèvre C, Wanteu T, Reache S, Dumont T, Nesbitt R, Dahl E, Gignoux E, Albela M, Righetti A, Bottineau MC, Cabrol JC, Sarafini M, Nzalapan S, Lechevalier P, Rambaud C, Rull M. A post-conflict vaccination campaign, Central African Republic. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2018 Aug 1:96(8):540-547. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.204321. Epub 2018 Jun 20

[PubMed PMID: 30104794]

[12]

Konan YL, Coulibaly ZI, Allali KB, Tétchi SM, Koné AB, Coulibaly D, Ekra KD, Doannio JM, Oudéhouri-Koudou P. [Management of the yellow fever epidemic in 2010 in Séguéla (Côte d'Ivoire): value of multidisciplinary investigation]. Sante publique (Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France). 2014 Nov-Dec:26(6):859-67

[PubMed PMID: 25629680]

[13]

Bassolé A. [In Burkina Faso: general mobilization in favor of the "vaccination commando"]. Hygie. 1986 Mar:5(1):31-4

[PubMed PMID: 3699829]

[14]

Zahouli JBZ, Koudou BG, Müller P, Malone D, Tano Y, Utzinger J. Urbanization is a main driver for the larval ecology of Aedes mosquitoes in arbovirus-endemic settings in south-eastern Côte d'Ivoire. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2017 Jul:11(7):e0005751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005751. Epub 2017 Jul 13

[PubMed PMID: 28704434]

[15]

Barte H, Horvath TH, Rutherford GW. Yellow fever vaccine for patients with HIV infection. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Jan 23:(1):CD010929. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010929.pub2. Epub 2014 Jan 23

[PubMed PMID: 24453061]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence