Introduction

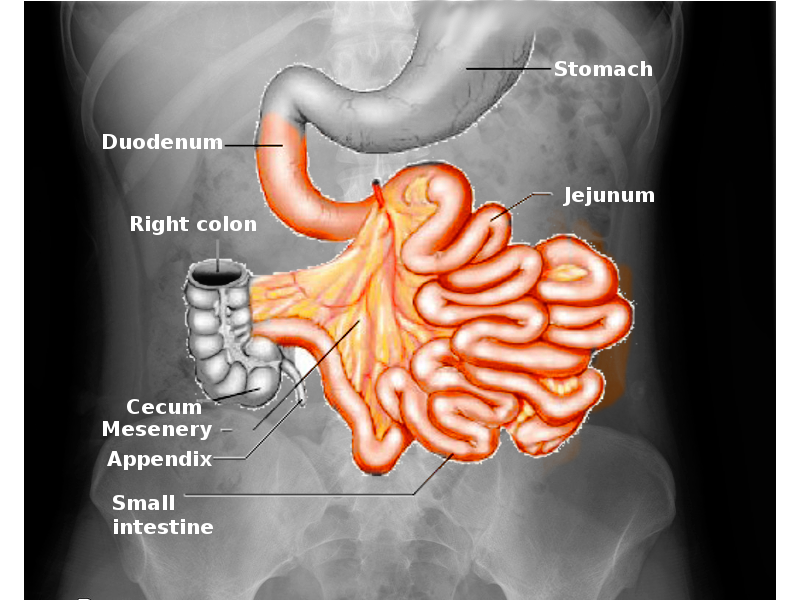

The small intestine is a crucial component of the digestive system that allows for the breakdown and absorption of important nutrients that permits the body to function at its peak performance. The small intestine accomplishes this via a complex network of blood vessels, nerves, and muscles that work together to achieve this task. It is a massive organ that has an average length of 3 to 5 meters. It divides into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.[1][2][3]

- The duodenum is the shortest section, on average measuring from 20 cm to 25 cm in length. Its proximal end is connected to the antrum of the stomach, separated by the pylorus, and the distal end blends into the beginning of the jejunum. The duodenum surrounds the pancreas, in the shape of a "C" and receives chyme from the stomach, pancreatic enzymes, and bile from the liver; this is the only part of the small intestines where Brunner's glands are present on histology.

- The jejunum is roughly 2.5 meters in length, contains plicae circulares (muscular flaps), and villi to absorb the products of digestion.

- The ileum is the final portion of the small intestine, measuring around 3 meters, and ends at the cecum. It absorbs any final nutrients, with major absorptive products being vitamin B12 and bile acids.

Layers of the Small Intestine

- Serosa: The serosa is the outside layer of the small intestine and consists of mesothelium and epithelium, which encircles the jejunum and ileum, and the anterior surface of the duodenum since the posterior side is retroperitoneal. The epithelial cells in the small intestine have a rapid renewal rate, with cells lasting for only 3 to 5 days.

- Muscularis: The muscularis consists of two smooth muscle layers, a thin outer longitudinal layer that shortens and elongates the gut, and a thicker inner circular layer of smooth muscle, which causes constriction. Nerves lie between these two layers and allow these to muscle layers to work together to propagate food in a proximal to distal direction.

- Submucosa: The submucosa consists of a layer of connective tissue that contains the blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics.

- Mucosa: The mucosa is the innermost layer and is designed for maximal absorption by being covered with villi protruding into the lumen that increases the surface area. The crypt layer of the small bowel that is the area of continual cell renewal and proliferation. Cells move from the crypts to the villi and change into either enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, or enteroendocrine cells.

Of importance is the mesentery, which is a double fold of the peritoneum that not only anchors the small intestines to the back of the abdominal wall, but also contains the blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that supply the small intestine.[4][5]

Structure and Function

The principal function of the small intestine is to break down food, absorb nutrients needed for the body, and get rid of the unnecessary components. It also plays a role in the immune system, acting as a barrier to a multitude of flora that inhabits the gut and to make sure no harmful bacteria enter the body.

- The duodenum is the initial portion of the small intestine and is where absorption actually begins. It is often described as being split into four parts: superior, descending, horizontal, and ascending. The superior portion is the only section that is peritoneal; the rest is retroperitoneal. Pancreatic enzymes enter the descending duodenum via the hepatopancreatic ampulla and break down chyme, a mix of stomach acid and food, from the stomach. Bicarbonate is also secreted into the duodenum to neutralize stomach acid before reaching the jejunum. Lastly, the liver introduces bile into the duodenum, which allows for the breakdown and absorption of lipids from food products. A significant landmark for the duodenum is the ligament of Trietz, a ligament made of skeletal muscle that tethers the duodenal-jejunal flexure to the posterior wall.

- The primary function of the jejunum is to absorb sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids. Both the jejunum and ileum are peritoneal.

- The ileum absorbs any remaining nutrients that did not get absorbed by the duodenum or jejunum, in particular vitamin B12, as well as bile acids that will go on to be recycled.

Embryology

The small intestine comes from the primitive gut, which forms from the endodermal lining. The endodermal layer gives rise to the inner epithelial lining of the digestive tract, which is surrounded by the splanchnic mesoderm that makes up the muscular connective tissue and all the other layers of the small intestine. The jejunum and ileum come from the midgut, whereas the duodenum derives from the foregut.

Villi and crypts make up the lining of the small intestine. Originally, the small intestine is lined by cuboidal cells up until the ninth week of gestation; then, villi begin to form. Crypt formation begins between the 10th to 12th weeks of gestation.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The arterial blood supply for the small intestine first comes from the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA).

- The superior pancreaticoduodenal artery is fed from the gastroduodenal artery, which branches from the proper hepatic artery, which is traceable back to the celiac trunk. It anastomoses with the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which comes from the SMA, to supply blood to the duodenum.

- The jejunum and ileum receive their blood supply from a rich network of arteries that travel through the mesentery and originate from the SMA. The multitude of arterial branches that split from the SMA is known as the arterial arcades, and they give rise to the vasa recta that deliver the blood to the jejunum and ileum.

The venous blood mimics that of the arterial supply, which coalesces into the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), which then joins with the splenic vein to form the portal vein.

Lymphatic drainage starts at the mucosa of the small intestine, into nodes next to the small intestine in the mesentery, to nodes near the arterial arcades, then to nodes near the SMA/SMV. Lymph then flows into the cisterna chyli and then up the thoracic ducts, and then empties into the venous system left internal jugular, and subclavian veins meet. The lymphatic drainage of the small intestine is a major transport system for absorbed lipids, the immune defense system, and the spread of cancer cells coming from the small intestine, explaining Virchow’s node enlargement from small intestine cancers.

Nerves

The nervous system of the small intestine is made up of the parasympathetic and sympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system. The parasympathetic fibers originate from the Vagus nerve and control secretions and motility. The sympathetic fibers come from three sets of splanchnic nerve ganglion cells located around the SMA. Motor impulses from these nerves control blood vessels, along with gut secretions and motility. Painful stimuli from the small intestine travel through the sympathetic fibers as well.

Muscles

Two layers of smooth muscle form the small intestine. The outermost layer is the thin, longitudinal muscle that contracts, relaxes, shortens, and lengthens the gut allowing food to move in one direction. The innermost layer is a thicker, circular muscle. This layer enables the gut to contract and break apart larger food particles. It also stops food from moving in the wrong direction by blocking the more proximal end. The two muscle layers work together to propagate food from the proximal end to the distal end.