Introduction

The thigh muscles subdivide into the anterior, medial, and posterior compartments. The function of the anterior compartment muscles is to extend the lower limb at the knee joint. The innervation of the anterior compartment of the thigh is from the femoral nerve, which originates from spinal roots L2-L4, and blood supply is from the femoral artery and its first branches. This anatomical region is crucial to human locomotion and dynamic movements, given the critical attachments of the quadriceps group to the patella and the resulting force exerted on knee extension.

Structure and Function

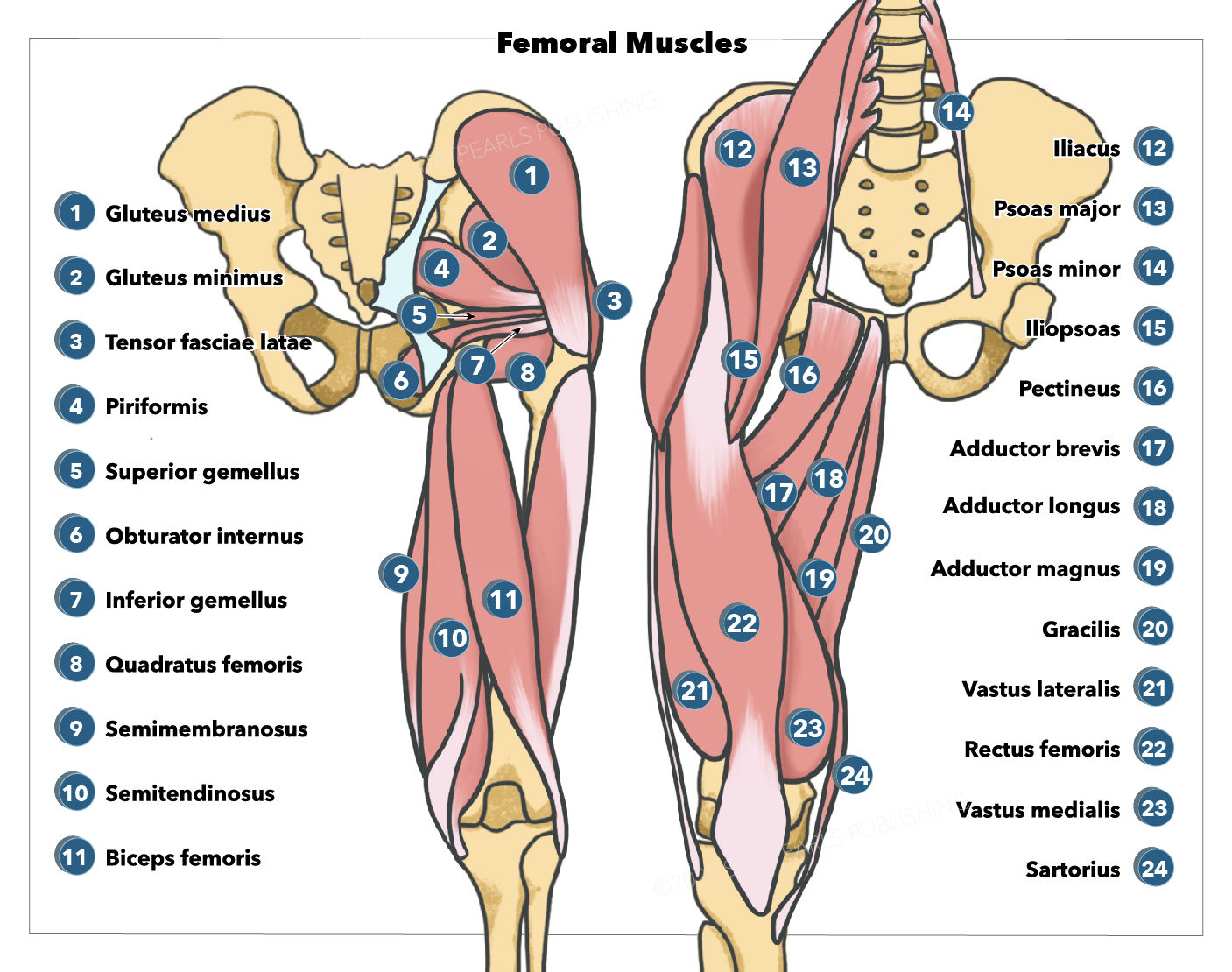

The function of the anterior compartment of the thigh is to extend the leg at the knee joint. Three major muscles (better described as two muscles and one muscle group) comprise the anterior compartment of the thigh — the pectineus, sartorius, and quadriceps femoris. Additionally, the end of the iliopsoas muscle passes through the anterior compartment.

Quadriceps Femoris

The quadriceps femoris is a group of four muscles: vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and rectus femoris. This group is the primary extensor of the knee.

The quadriceps femoris connects to the patella via the quadriceps tendon, which then extends to insert at the tuberosity of the tibia.[1] It receives innervation by the femoral nerve. The vastus muscles are responsible for knee extension and stabilization of the patella. The rectus femoris is responsible for thigh flexion at the hip and knee extension.

The vastus lateralis is the largest of the four muscles. It originates from the greater trochanter and lateral lip of linea aspera and inserts at the lateral base and border of the patella, forming the lateral patellar retinaculum and the lateral side of the quadriceps femoris tendon.

The vastus medialis originates at the inferior portion of the intertrochanteric line and medial lip of the linea aspera. It inserts at the medial base and border of the patella, forming the medial patellar retinaculum and the medial side of the quadriceps femoris tendon.[2]

The vastus intermedius originates at the anterior and lateral surfaces of the femoral shaft. It inserts at the lateral border of the patella, forming the deep portion of the quadriceps tendon.[2]

The rectus femoris is comprised of two proximal heads: the straight head, originating at the anterior inferior iliac spine (ASIS) of the ilium, and the reflected head, originating from a groove superior to the acetabulum. The two heads converge to join as the anterior part of the quadriceps femoris tendon.[3]

Sartorius

The sartorius muscle is responsible for flexion of the knee and flexion and lateral rotation of the hip joint and is the longest muscle in the body. It is positioned more superficially in the leg than the other muscles in the anterior thigh; the long parallel fibers run anteriorly from lateral to medial over the quadriceps. The sartorius originates from the ASIS and inserts at the superior, medial surface of the tibia, and it is innervated by the femoral nerve.[4]

Pectineus

The pectineus muscle is responsible for flexion, adduction, and medial rotation of the hip. The pectineus forms the base of the femoral triangle and is flat and quadrangular in shape. The pectineus is considered a transitional muscle between the anterior and medial thigh; this is due to innervation mainly from the femoral nerve and sometimes from the obturator nerve. The pectineus muscle originates at the pectineal line of the pubis and inserts at the posterior aspect of the femur, immediately inferior to the lesser trochanter.[5]

Iliopsoas

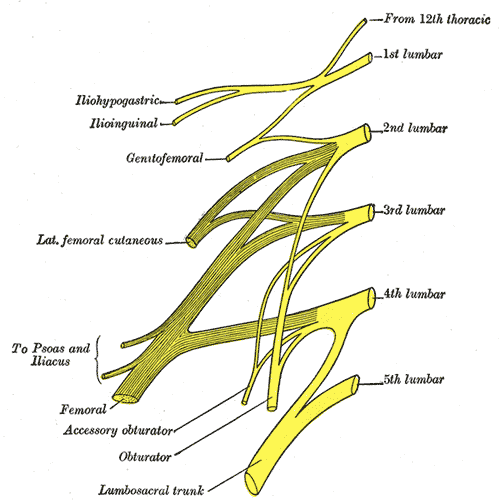

The iliopsoas muscle does not cross the knee joint and is responsible for flexion of the thigh and lateral rotation of the hip. The iliopsoas consists of two muscles: the psoas major and the iliacus. The psoas major originates in the lumbar vertebrae, and the iliacus originates from the iliac fossa of the pelvis. Both muscles insert onto the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas major is innervated by the short collateral branches of the lumbar plexus (L1-L3), while the femoral nerve (L1-L4) innervates the iliacus muscle.

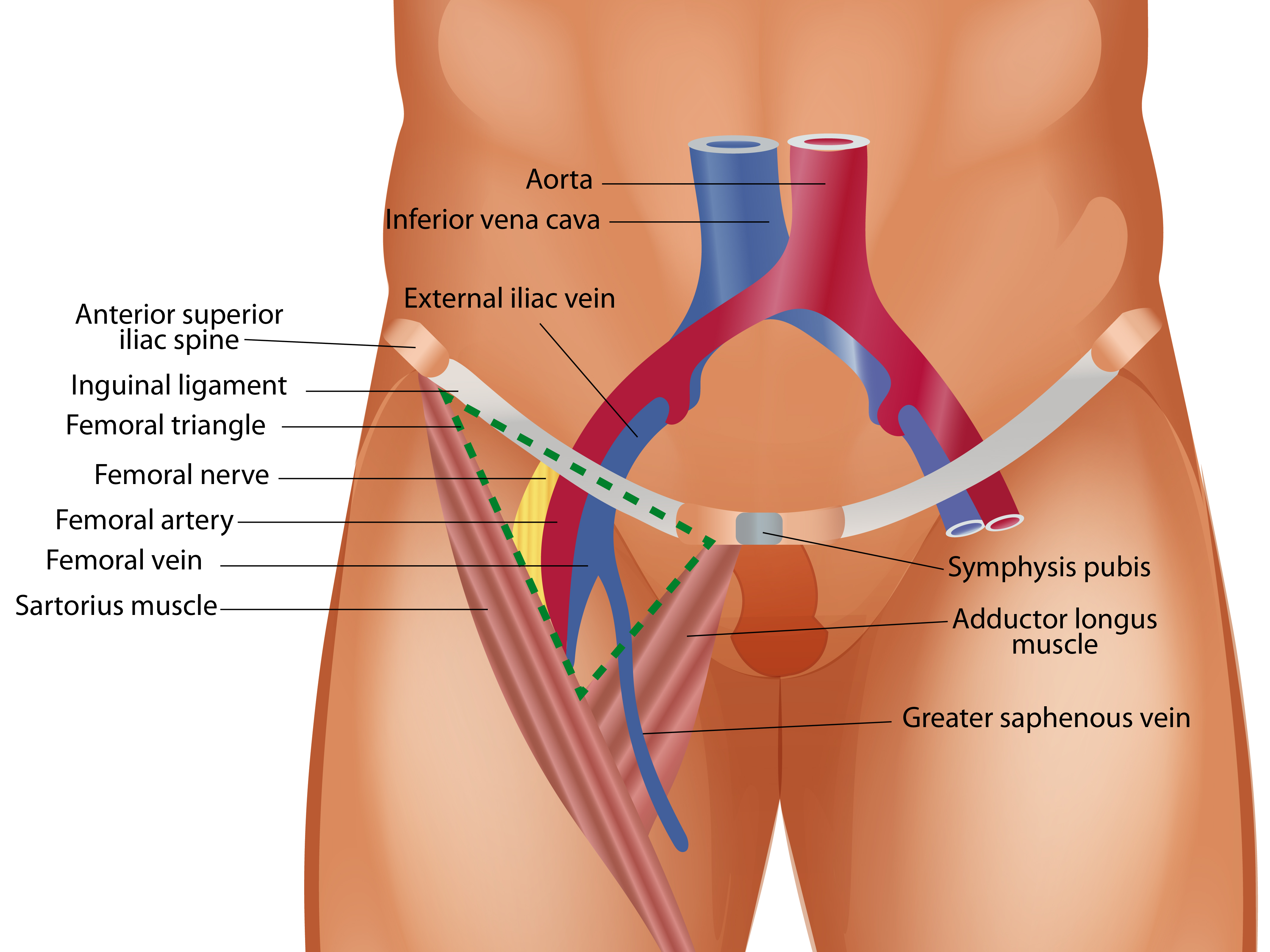

Adductor Canal

The adductor canal is an important anatomical space of the anterior thigh region because it is a neurovascular conduit carrying the femoral artery, femoral vein, saphenous nerve, and the nerve to vastus medialis.[6] It is roofed by a fascial layer on which the sartorius lies, and the medial and lateral walls are defined by the adductor muscles and the vastus medialis, respectively.[7] Its floor is also muscular, with the adductor longus occupying the upper part of the floor and the adductor magnus occupying the floor below it.

Embryology

At five weeks of development, the lower limb bud begins to appear. It grows laterally from the L2 through S2 segments. The embryological development of the apical ectoderm ridge gives rise to the cell precursors necessary for anterior thigh muscle development.[8] The cell precursors known as mesenchyme differentiate away from the apical ectoderm ridge and give rise to the muscles that make up the limb bud and, eventually, the anterior thigh muscles. Once there is a 90-degree rotation of the lower limb medially along the longitudinal axis, the knee moves to an anterior position.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

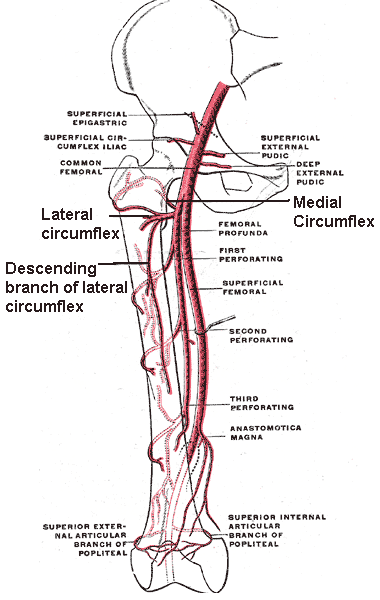

The femoral artery supplies blood to the anterior compartment of the thigh. The artery enters the thigh by passing under the inguinal ligament at the mid-inguinal point, the halfway point between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the pubic symphysis. The largest branch of the femoral artery is the deep femoral artery. It branches further into the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, with significant inter-individual variability of their origins. It runs around the head of the femur to supply the surrounding musculature.[9]

The external iliac lymphatic plexus is the lymphatic system that drains the muscles in the anterior compartment of the thigh, which merges into the common iliac plexus, further draining into the cisterna chyli and then the thoracic duct.[10]

Nerves

The femoral nerve innervates the sartorius, pectineus, quadriceps femoris, and iliacus muscle of the iliopsoas. It receives nerve supply from the nerve roots L2-L4, innervating both the hip flexor and quadriceps muscle groups. The femoral nerve is also responsible for anterior thigh and medial leg sensation. The motor division of the femoral nerve is further divided into anterior and posterior divisions.

The anterior motor division innervates the: sartorius, pectineus (sometimes the obturator nerve also provides additional innervation), iliacus (from the muscular branches of the femoral nerve L1 through L3)[11]

The posterior motor division innervates the quadriceps femoris muscle group (vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and rectus femoris).[11]

Surgical Considerations

Thorough knowledge of regional anatomy is crucial to operating safely, avoiding neurovascular injury, and correctly identifying intermuscular planes in the region. Knowledge of anatomy allows the surgeon to find the area of the pathology, and understanding of the origins and insertions of the muscles helps to find a tendinous portion appropriate for graft reconstruction. Identifying the correct nerves when performing peripheral nerve blocks is essential.

One of the most common surgical approaches in orthopedics involving the anterior compartment of the thigh is the lateral approach to the femur.[12][13] This procedure is useful for open reduction and plate fixation for various proximal, middle, and distal femur fractures. The lateral approach involves marking out the skin at the level of the fracture. Following a skin incision, an incision is cut through the subcutaneous tissue and then through a thick band-like structure called the tensor fascia lata (TFL). This structure is easy to find, has a glistening white appearance, and is repairable at the time of wound closure. Once through the TFL, the vastus lateralis can be split, giving access to the femur.

Alternatively, one can take a 'subvastus' approach by going posterior to the vastus lateralis and elevating it subperiostially off the bone.[14]

Clinical Significance

In addition to a complete history and physical examination, it is essential to understand the anatomy of the musculature in the anterior compartment of the thigh to effectively diagnose and formulate a treatment plan for patients. Muscle pain and weakness may accompany a nerve injury. Femoral nerve damage often results in loss of hip flexion and leg extension; this is especially important in distinguishing between focal injuries and systemic conditions.[15]

Snapping Hip Syndrome

Snapping hip syndrome, or coxa saltans, is found in approximately 10% of the populations with a particular propensity for professional sporting athletes and dancers.[16] It is usually a painless clinical phenomenon in which the patient can hear or feel a snapping sound or sensation when flexing the hip. The most common cause is the iliotibial tract sliding over the greater trochanter. Other causes, however, include abnormal movement of the iliopsoas tendon over the iliopectineal eminence.[17] Rarer causes include labral tears, synovial osteochondromatosis, or intra-articular bodies.[18] Treatment depends variably on the cause and clinical and functional effects on the patient; it can range from conservative treatment and physiotherapy to surgical intervention to correct an anatomical defect.[16]