Structure and Function

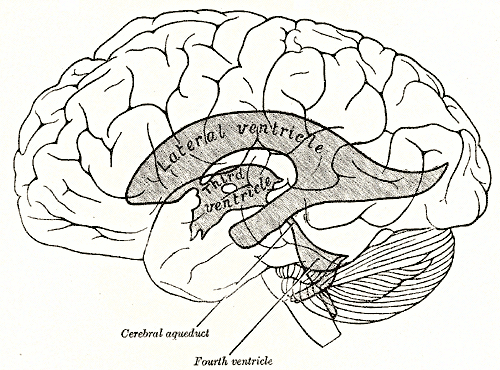

The cerebral ventricular system is made up of 4 ventricles that include 2 lateral ventricles (1 in each cerebral hemisphere), the third ventricle in the diencephalon, and the fourth ventricle in the hindbrain. Inferiorly, it is continuous with the central canal of the spinal cord. The fluid inside the ventricular system and subarachnoid space is called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is produced by specialized ependymal cells of the choroid plexus within the ventricular system. After circulating through the ventricular system, they return t the circulation through the arachnoid granulations.

Lateral Ventricle

The lateral ventricle is a C-shaped cavity situated within each cerebral hemisphere. It is lined by ependyma and filled with CSF. It has a capacity of 7 to 10 ml. The 2 lateral ventricles are separated from each other by a thin vertical sheet of nervous tissue called septum pellucidum covered on either side by ependyma. It communicates with the third ventricle through the interventricular foramen of Monro. Each of the lateral ventricles is made a central part (body) and 3 horns (cornua) namely the anterior horn, posterior horn, and inferior horn. On the coronal section, it appears triangular anteriorly and rectangular posteriorly.

Central Part (Body)

The central part lies within the parietal lobe. It extends from the interventricular foramen anteriorly to the splenium of the corpus callosum posteriorly. The roof is formed by the inferior surface of the body of the corpus callosum. The medial wall is formed by the septum pellucidum majorly and the body of the fornix in the lower part.

The floor is concave and is formed by the following structures in the lateral to medial order:

- The body of the caudate nucleus (a small bundle of white fibers)

- Stria terminalis and thalamostriate vein

- The lateral part of the superior surface of the thalamus

- Choroid plexus that invaginate into the lateral ventricle through a slit space between the fornix and upper surface of thalamus, choroid fissure

Anterior Horn

The anterior horn moves forward and slightly lateral and downward to lie in the frontal lobe, so also referred to as the frontal horn. It has a roof, a floor, anterior and medial wall.

The anterior wall is formed by the posterior surface of the genu of the corpus callosum and the rostrum. The roof is formed by the inferior surface or anterior part of the body of the corpus callosum. The medial wall is formed by the septum pellucidum.

The floor is formed majorly by the head of the caudate nucleus, while a small portion on the medial side is formed by the upper surface of the rostrum of the corpus callosum.

Posterior Horn

This is also named occipital horn as it curves backward and medially to lie in the occipital lobe and is frequently asymmetrical.

The roof and lateral wall are formed by the sheet of fibers of corpus callosum known as tapetum. This separates the posteriorly sweeping optic radiation from the cavity of the posterior horn.

The medial wall has 2 bulges. In the upper part, it is formed by the fibers of the occipital lobe sweeping backward known as forceps major and is referred to as the bulb of the posterior horn. The second elevation below this is called calcar avis and corresponds to the in-folding of the anterior part of the calcarine sulcus.

Inferior Horn

This is the largest and longest of the 3 horns. It forms a curve around the posterior end of the thalamus, descending posterolaterally and then anteriorly into the temporal lobe. The area where the inferior horn and posterior horn diverge is called collateral trigone or atrium.

Laterally, the roof is covered by the inferior surface of the tapetum of the corpus callosum and medially by the tail of the caudate nucleus and stria terminalis. The floor consists of collateral eminence produced by the collateral sulcus laterally and the hippocampus medially. The fibers of the hippocampus form a thin layer of white matter called alveus that covers the ventricular surface and converge medially to form the fimbria. Most medially on the floor lies the choroid plexus passing through the choroid fissure.

There exists an asymmetry between the lateral ventricles with an incidence of 5% to 12%. Studies have imputed this to various factors like brain dominance, early brain lesions, intrauterine, or postnatal compression skull.[2]

Foramen of Monroe

The size and shape of the foramen depend on the size of the ventricles. If the ventricles are small, each foramen is crescent-shaped. As the ventricular size increases, the foramen assumes a rounded shape. Through this passes the medial posterior choroidal arteries, superior choroidal vein, and the septal veins.[3]

Third Ventricle

The third ventricle is a median slit-like cavity situated between the 2 thalami and part of the hypothalamus. In the anterosuperior aspect, it communicates with the lateral ventricles while on its posteroinferior aspect it communicates with the fourth ventricle through the cerebral aqueduct of Sylvius. The space of the third ventricle is lined by ependyma and is traversed by a mass of grey matter called interthalamic adhesion or Massa intermedia, located posterior to the foramen of Monroe and connects the 2 thalami. It may be absent in about 30% of human brains. It has a roof, a floor, anterior and posterior wall, and 2 lateral walls.

The anterior wall is formed from above downward by:

- Anterior columns of fornix that diverge laterally into the lateral walls.

- Anterior commissure

- Lamina terminalis, which is a thin sheet of grey matter that extends from the rostrum of the corpus callosum superiorly to optic chiasma inferiorly.

The posterior wall is formed from above downward by:

- Pineal gland

- Posterior commissure

- Cerebral aqueduct

The roof is formed by a sheet of ependyma connecting the upper border of the lateral wall of the ventricle. It is covered by a triangular fold of pia mater called tela choroidea. Two longitudinal vascular fringes hang downward from tela choroidea and form the choroid plexus of the third ventricle.

The lateral wall consists of a curved hypothalamic sulcus extending from the interventricular foramen to the cerebral aqueduct. The sulcus divides the lateral wall into 2 parts:

- Larger upper part: Formed by the medial surface of the anterior two-thirds of the thalamus

- Smaller lower part: Formed by the hypothalamus and is continuous with the floor.

The floor descends ventrally and is formed from before backward by:

- Optic chiasma

- Tuber cinereum and infundibulum

- Mammillary body

- Posterior perforated substance

- Tegmentum of midbrain

The third ventricle protrudes into the surrounding structure in the form of recesses. There are 5 following recesses:

- Infundibular recess: It is a deep recess protruding downwards from the tuber cinereum into the pituitary stalk i.e infundibulum.

- Optic recess: It is an angular recess situated at the junction of the anterior wall and the floor. Its anterior wall is formed by lamina terminalis and the posteroinferior wall by optic chiasma.

- Anterior recess (vulva of the ventricle): It is a diverticulum that is bounded anteriorly by the anterior commissure and posteriorly by the diverging columns of the fornix.

- Pineal recess: It is a small outpouching that extends into the stalk of the pineal body.

- Surprapineal recess: It is a diverticulum that lies anterosuperior to pineal recess and is lined by ependyma. It normally measures 2 to 3 mm. It is named as the pressure diverticulum of the third ventricle as it becomes distended in the case of hypertensive hydrocephalus.[4]

Aqueduct of Sylvius

The Sylvian aqueduct is the narrowest part of the ventricular system of the brain. It measures 18 mm approximately and is the most common site for the interventricular blockade. It has been observed that the luminal size of the aqueduct reduces from the second fetal month due to the development of surrounding neural tissue.[5]

Fourth Ventricle

The fourth ventricle is a broad, tent-like cavity of the hindbrain filled with CSF. It is bounded anteriorly by the pons and cranial half of medulla and posteriorly by the cerebellum. It appears triangular on the sagittal section and rhomboidal on a horizontal section. Superiorly, it is continuous with the cerebral aqueduct while inferiorly it is continuous with the central canal of the spinal cord.

Recesses of the Fourth Ventricle

There are 5 recesses:

- Lateral recess: There are 2 on either side, between the inferior cerebellar peduncle and the peduncle of flocculus dorsally. Anteriorly, it is crossed by the branch of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve. Laterally, it extends into the subarachnoid space through an aperture called the foramen of Luschka. Through this foramen, a part of the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle also protrudes.

- A medial dorsal recess that extends into the white core of cerebellum

- Two lateral dorsal recess on either side of median dorsal recess above the inferior medullary velum

Boundaries

Lateral wall: The fourth ventricle is bounded inferolaterally by gracile and cuneate tubercles and inferior cerebellar peduncles and superolaterally by the superior cerebellar peduncle.

Dorsal wall (Roof): The cephalic portion of the roof is formed by 2 superior cerebellar peduncles whose medial margins overlap the ventricle on reaching the inferior colliculi. A thin sheet of white matter called superior medullary velum bridges the gap between the superior cerebellar peduncle. It is covered dorsally by the lingula of the superior vermis of the cerebellum.

The lower half of the roof is covered by a thin sheet of non-nervous tissue, the inferior medullary velum, which is formed by the ventricular ependyma and the tela choroidea of the fourth ventricle. The lower part of inferior medullary velum has a large midline aperture called the foramen of Magendie through which the fourth ventricle communicates with the subarachnoid space of the cerebellomedullary cistern, i.e., cisterna magna.

The tela choroidea of the fourth ventricle is a double layer fold of pia-mater. The dorsal layer lines the inferior vermis and is reflected upon itself to form the ventral layer on reaching the nodule of the cerebellum. Laterally, it meets the inferolateral border of the ventricular floor marked by a white ridge called Taenia. Inferiorly, the 2 taeniae meet to form a small fold called obex while superiorly it passes along the lateral recess. The 2 layers of tela choroidea enclose the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle in the form of vascular fringes. The plexus assumes a "T" shape with a vertical and horizontal limb. The vertical limb 2 long fringes in the median plane fused at the cranial end while the horizontal limb continues in the lateral recess through the aperture foramen of Luschka into the subarachnoid space. In certain cases, this foramen is closed by a membrane. This forms a pouch containing choroid plexus at the cerebellopontine angle called Bochdalek's flower basket. Enlargement of this pouch may give rise to clinical symptoms.[6]

Floor: The floor is formed by the posterior surface of the pons and upper medulla. It is rhomboid/diamond-shaped, so often called rhomboid fossa.

It is divisible into 3 parts:

- An upper triangular part formed by the posterior surface of the pons.

- A lower triangular part formed by the posterior surface of the upper medulla.

- The intermediate part is formed by the base of the upper triangular part above and by a line joining the taenia below. Delicate bundles of transversely arranged fibers are present on the surface called striae medullaris.

The floor of the fourth ventricle is divided by a median sulcus into symmetrical halves. Either side of the sulcus presents an elevation, the median eminence, which is bounded laterally by the sulcus limitans. The upper end of sulcus limitans widens into 2 small depressions called the superior fovea. Above the superior fovea is present a bluish-grey area called locus coeruleus which owes its color to the underlying group of pigmented nerve cells called substantia ferruginea. These neurons secrete large amounts of norepinephrine as well. The area lying lateral to the sulcus limitans is called vestibular area and lies partially in the pons and partially in the medulla.

On the pontine part of the floor, the median eminence shows an oval swelling opposite superior fovea called facial colliculus, produced by the hooking of motor fibers of facial nerve around the abducent nerve.

The lowest part of sulcus limitans presents a dimple called the inferior fovea. Below the inferior fovea, sulcus limitans descends obliquely towards the median sulcus dividing the medial eminence into a hypoglossal triangle above and a vagal triangle below. A faint furrow divides the hypoglossal triangle into a medial part, which overlies the nucleus of the hypoglossal nerve, and a lateral part, which overlies the nucleus intercalatus. The vagal triangle overlies the dorsal nucleus of the vagal nerve. It is crossed by a narrow translucent ridge called funiculus separans. The area bounded by funiculus separans above and the gracile tubercle below is called area postrema consisting of highly vascular, glial tissue.

Histology

The ventricular system of the brain is lined by a special type of cells called ependymocytes (ependyma). It is a cuboidal or columnar epithelium derived from the neuroepithelium. The choroid plexus is a tuft of permeable capillaries in a matrix of connective tissue and is responsible for CSF production and lies just below the ependymal layer.

A layer of subependymal glial cells is present below the ependyma. These cells interlock with the astrocyte processes and form a tight junction called the blood-brain barrier. However, there are specific areas that lack this barrier called circumventricular organs (CVOs). They have fenestrated capillaries with very high permeability and have sensory as well as secretory function. These are the pineal gland, median eminence, neurohypophysis, subcommissural organs, subfornical organ, area postrema, and organum vasculosum of lamina terminalis.[7]

The beating of the cilia is critical for the movement of CSF. Thus, the ciliary movement should be oriented in the anteroposterior neuroaxis. An implication of this has been observed in a condition called primary ciliary dyskinesia. The incidence of hydrocephalus is high in mouse models with primary ciliary dyskinesia compared to humans. This provides insight into genetic mechanisms that regulate the susceptibility to hydrocephalus in ciliary dysfunction of ependyma.

Embryology

The ventricular system develops from a single cavity, i.e., hollow of the neural tube. The neural tube is formed around the fourth week of gestation. Shortly after that, the spinal neurocele closes, and this separates the amniotic cavity from the neural cavity.

Three dilatations are formed from cephalic to caudal end namely prosencephalon (forebrain), mesencephalon (midbrain), and rhombencephalon (hindbrain). Prosencephalon develops into telencephalon (cerebral hemisphere) and diencephalon. Rhombencephalon develops into the metencephalon (pons and cerebellum) and myelencephalon (medulla oblongata). These developing vesicles contain respective vesicles within them as follows:

- The telencephalic cavity becomes lateral ventricles

- The diencephalic cavity becomes the third ventricle

- The narrowed mesencephalic cavity develops into the cerebral aqueduct

- the rhombencephalic cavity becomes the fourth ventricle

During early development, ventricles proliferate and assume adult size. After that, the brain tissue begins to grow in caudal to cephalic direction than the ventricles, and this differential growth gives rise to adult ventricular shape.

Surgical Considerations

Access to the cerebral ventricular system is one of the important approaches in neurosurgery.

Ventriculostomy

Ventriculostomy is one of the most common procedures in neurosurgery. It involves creating a hole in the ventricles for CSF drainage and monitoring of intracranial pressure (ICP). It is also referred to by the term external ventricular drain (EVD). The commonest entry point on the skull is Kocher's point which is 11 cm posterior to the glabella and 3 to 4 cm lateral to the midline. This allows entry into the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle.[8]

Ventricular Shunting

This is another procedure in which CSF is diverted to other body compartments like the peritoneal cavity (ventriculoperitoneal shunt), right atrium (ventriculoatrial shunt), pleural space (ventriculopleural shunt).

Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy

This is a modern surgical method performed endoscopically where an incision is made on the floor of the third ventricle to drain the CSF directly into the basal cisterns.

Clinical Significance

Any disturbance in the free flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the ventricular system leads to hydrocephalus in which there is excessive fluid accumulation in the brain. This leads to abnormal widening of the cerebral ventricle and raised ICP. The symptoms include vomiting, headache, irritability, blurred vision, gait disturbance, drowsiness, among others. In infants, the main sign is a rapid increase in head circumference.

Hydrocephalus can be communicating type (when CSF flow is not blocked) or non-communicating type (when CSF flow is blocked anywhere along the narrow passages connecting the ventricles). It is also classified as either congenital or acquired. The most common cause of congenital hydrocephalus is aqueductal stenosis while acquired hydrocephalus can be caused by etiologies like a tumor, trauma, infection, hemorrhage, among others. Communicating hydrocephalus is caused by impaired absorption of CSF by the arachnoid granulations which may be the consequence of any leptomeningeal processes such as hemorrhage as in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage or inflammation as in pyogenic fungal tuberculous or carcinomatous meningitis.

Aqueductal stenosis occurs genetically in the case of aqueductal atresia or can be acquired in the case of ependymitis or tumor of surrounding structures compressing the aqueduct. This leads to the dilation of both lateral and third ventricles with a normal fourth ventricle. X-linked hydrocephalus is a rare condition that presents with narrowing of Sylvian aqueduct, muscle stiffness, and permanently adducted thumbs.

A colloid cyst is a benign intracranial tumor occurring in the anterior and anterosuperior part of the third ventricle and can occasionally obstruct the foramen of Monroe, causing dilatation of one or both lateral ventricles. They have no intrinsic pathology but produce symptoms due to their obstructive nature.[3][9]

Dandy-Walker malformation is a condition characterized by a complete absence of the cerebellar vermis. The key feature of this condition is the enlargement of the fourth ventricle.

The foramen of Luschka and Magendie may be obstructed in a condition called Arnold-Chiari malformation where the cerebellar tonsils get displaced downward through the foramen magnum and can give rise to internal hydrocephalus. They can also be obstructed in the case of inflammatory fibrosis of the meninges leading to congenital hydrocephalus.[5]

Cavum septi pellucidi is a slit-like space in the anterior part of septum pellucidum and has a vital role in the sonographic assessment of the fetal brain. It is believed to be closely associated with the development of corpus callosum. The presence of cavum septi pellucidi in fetal sonography excludes complete agenesis of the corpus callosum.[10][11][10] An acquired cavum septum pellucidum is a relatively common finding radiologically or pathologically in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.