Introduction

The pelvis is a group of fused bones and may be considered the first step in the linkage of the axial skeleton (bones of the head, neck, and vertebrae) to the lower appendages. The part of the axial skeleton directly communicating with the pelvis is the lumbar spinal column. The femur is the appendicular skeletal bone connected to the pelvis at the acetabulum, a bony ring formed by the fusion of three bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The main function of the pelvis is support for locomotion, as it provides attachment points for muscles, tendons, and ligaments. While stiff joints bind the axial skeleton to the pelvis, the appendicular skeleton is joined via a relatively free-floating ball and socket joint between the femur and the acetabulum to allow maximal mobility of the joint.[1]

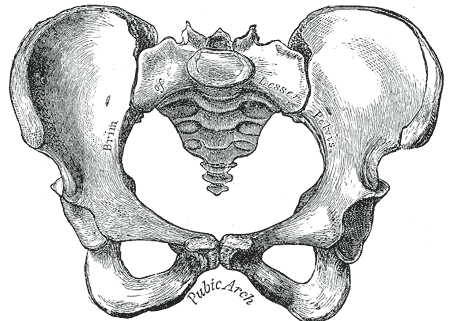

In discussing the pelvis, a distinction can be made between the "pelvic spine" and the "pelvic girdle." The pelvic girdle, also known as the os coxae, Latin for “bone of the hip,” consists of the fused bones identified individually as the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The ring of this girdle is closed in the anterior by the pubic symphysis between the left and right pubic bones, and in the posterior between the left and right ilia and the sacrum at the sacroiliac joints. The pelvic spine consists of the sacrum and coccyx. Together these two parts form the bony pelvis.

Structure and Function

The adage “structure informs function” rings true in the pelvis. The os coxae, or hip bones as they are known colloquially, are attached dorsally to the sacrum by sacroiliac ligaments. In addition to the ligaments of this joint, the interposing areas of the sacrum and the ilium have matching, irregular contours to increase joint strength. The relatively fixed joint between the sacrum and the lumbar spine is ideal for bearing the load of the upper body. At the most ventral area of the pelvis, there is a fibrocartilaginous joint in the pubic symphysis. It is amphiarthrotic, meaning that it is quite firm but allows limited movement similar to the intervertebral joints. This allows the joint to resist shearing forces during movement while still accommodating expansion during labor.

Three major ligaments stabilize the femur in the acetabulum, one for each part of the os coxae. The iliofemoral ligament is the most anterior and has a “Y” appearance. It works to prevent hyperextension of the hip. The ischiofemoral ligament is posterior and works to prevent over-abduction along with the pubofemoral ligament located medially. All of these ligaments attach to the acetabular labrum, which is a lip of connective tissue around the acetabulum that deepens the socket of the ball-and-socket joint to increase stability and resist dislocation.

Other ligaments of note in the acetabulum are the transverse acetabular ligament and the ligament of the head of the femur, or ligamentum teres femoris (Latin for round ligament of the femur.) The transverse acetabular ligament is a strong band of connective fibers that traverse the acetabular notch on the inferior aspect of the acetabulum, this creates a foramen for nutrient-supplying blood vessels to enter the hip joint while still maintaining the structural integrity of the joint. Much as its name implies, the ligament of the head of the femur is connected to the head of the femur at the center of the acetabulum. However, rather than providing support, its main function is to house the artery to the head of the femur, which provides blood to the head of the femur via a branch from the obturator artery. Disruption in perfusion to the femoral head from any cause can result in degradation and even collapse of the femur inside the acetabulum. This disease process is known as avascular necrosis or Legg-Calve-Perthes disease in children.

There are two notches of note in the bony pelvis: the greater and lesser sciatic notches. The greater notch is on the ileum, whereas the lesser sciatic notch is located inferiorly on the ischium just below the ischial spine. The sacrotuberous ligament runs from the sacrum to the ischial tuberosities and crosses near the greater sciatic notch to form the greater sciatic foramen. Similarly, the sacrospinous ligament runs from the sacrum to the ischial spine to form the lesser sciatic foramen. The greater sciatic foramen contains multiple clinically notable structures, such as the sciatic nerve, the superior and inferior gluteal nerves, the pudendal nerve, the nerve to quadratus femoris, nerve to obturator internus, as well as the superior and inferior gluteal vessels and internal pudendal vessels. Finally, the piriformis also passes through this foramen. The lesser sciatic foramen contains the tendon of obturator internus, as well as the pudendal nerve and vessels coming from the greater foramen on their way to the perineum and gonads. Although somewhat controversial, it is considered possible for the piriformis muscle to cause nerve entrapment, known as piriformis syndrome. It presents with symptoms of sciatica and tenderness near the sciatic notch but remains a diagnosis of exclusion.[2]

Another eye-catching structure in the os coxae is the obturator foramen. The superior and inferior rami of the ischium and pubis bones come together to form this ring-like structure on each side of the pelvis. This ring is covered by the obturator membrane, which leaves a small opening known as the obturator canal through which the obturator neurovascular bundle passes. The internal and external sides of the membrane are connected to the respectively named internal and external obturator muscles responsible for external rotation of the hip and stabilization during ambulation.

The pelvis has both an inlet and an outlet, also known as the superior and inferior apertures, as it forms somewhat of a funnel. The pelvic inlet is marked by the pelvic brim, a bony ring made up of the sacral prominence posteriorly, the arcuate line of the ilium laterally, and the pectineal line of the pubis and pubic symphysis anteriorly. The wings of the ilium extending above this line form the greater, or “false” pelvis, and the area below this line forms the lesser or “true” pelvis. The outlet of the pelvis is marked posteromedially by the coccyx, posterolaterally by the sacrotuberous ligaments connecting the sacrum to the ischial tuberosities, laterally by the ischial bones, and anteriorly by the pubic arch of the pubic bones.

The pelvis has a "floor" at this outlet that serves multiple functions. The first function is to contain the visceral organs in the caudal region of the pelvis and help prevent organ prolapse through the pelvic outlet. The second function is to maintain the continence of the anus and urinary tract through several layers of musculature and ligaments. These pelvic floor muscles are complex and will be described further in the “Muscles” section.

Embryology

The earliest appendicular skeletal elements appear at approximately 28 days, which coincides with the appearance of limb buds. Condensation of mesenchymal tissue in the limb buds become scaffolds for bone formation in the fifth week. These models undergo chondrification to form hyaline cartilage beginning in the sixth week. At this point, imaging can discern a basic skeletal system. By the time the fetus reaches the gestational age of nine weeks (seven weeks after fertilization), chondrification centers in the ilium, ischium, and pubis first appear and grow rapidly. The following week the first ossification center begins to replace cartilage in the iliac crest. At the same time, the fusion of the sacrum and ilium occurs. After the tenth week of gestation, the fusion of all the bones of the pelvic girdle has occurred. Secondary ossification continues postnatally, and complete ossification is not achieved until adulthood. [3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The aorta bifurcates into the common iliac arteries at the level of the L4 vertebra. At the pelvic brim, the common iliac arteries bifurcate into the internal and external iliac arteries. The external iliac exits the pelvis underneath the inguinal ligament and becomes the femoral artery to supply the lower extremity with blood. The internal iliac artery supplies the pelvic organs, perineal floor, and gluteal muscles with blood. It has 2 major branches, known as the anterior and posterior divisions.

The anterior division supplies the upper part of the bladder via the superior vesicular artery and umbilical artery in the fetus. In adults the umbilical artery becomes obliterated and the remnant is known as the medial umbilical ligament. The trigone of the bladder, prostate, and seminal glands are supplied with blood by the inferior vesical artery. The internal pudendal artery supplies the perineal muscles and skin as well as the penis and clitoris. The middle rectal artery supplies the rectum with blood. The obturator artery supplies the pelvic floor, head of the femur, and ilium. The inferior gluteal artery provides circulation to the gluteal region, head of the femur, upper thigh, and sciatic nerve. In women, the uterine artery supplies blood to the uterus, fallopian tube, ovary, cervix, and vagina.

The posterior division includes three main branches. The iliolumbar artery supplies blood to the psoas major, iliacus, and quadratus lumborum muscles. The lateral sacral arteries supply blood to the sacral meninges and skin over the sacrum as well as the coccyx where it anastomoses with the middle sacral artery from the aorta. The superior gluteal artery supplies blood to the gluteal muscles and anastomoses around the hip as well as the ASIS.

The ovarian artery branches from the aorta and travels within the suspensory ligament of the ovary to supply blood to the ovaries. The testicular arteries also originate from the aorta and pass through the inguinal canal to supply the testes.

There are several groups of lymph nodes in the pelvis. Some surround vasculature like the external, internal, and common iliac nodes. There are also sacral, pararectal, lumber, and inguinal nodes. These nodes are important in staging the spread of cancers in the pelvic area and can even be used to localize malignancies based on nodal involvement. For example, the testes, ovaries, and uterus drain to para-aortic nodes, while the lower rectum, bladder, vagina, cervix, and prostate drain into the internal iliac nodes. Lastly, the anal canal, scrotum, vulva, and most of the skin below the umbilicus drain into the superficial inguinal nodes.

Nerves

There are multiple plexuses of nerves that provide motor and sensory innervation to the pelvis. [4]

The sacral plexus arises from L4-S4 spinal nerves. It includes the largest nerve in the body, the sciatic nerve, which contains nerves from spinal levels L4-S3. The sciatic nerve innervates most of the skin of the leg as well as many muscles of the thigh and leg. It is composed of two bundles of nerve tracts, called the tibial and fibular division, which split at the level of the knee into the tibial and fibular nerves. The pudendal nerve (S2-S4) innervates the skin and muscles of the perineum. The superior gluteal nerve (L4-S1) and the inferior gluteal nerve (L5-S2) innervate the gluteal muscles. The nerve to the quadratus femoris (L4-S1) innervates the quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior muscles of the hip. The nerve to the obturator internus muscle (L5-S2) innervates said muscle. The nerve to the piriformis (S1-S2) similarly innervates its eponymous muscle. The perforating cutaneous nerve (S2-S3) innervates the medial and lower part of the buttock. The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve (S2-S3) innervates the skin on the posterior thigh/leg and the perineum. The pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-S4) provide parasympathetic innervation to pelvic organs.

The coccygeal plexus (S4-S5) and coccygeal nerves innervate the coccygeus and levator ani muscles, as well as the skin immediately dorsal to the anus.

The lumbar plexus (L2-L4) gives rise to the obturator nerve that innervates the skin of the medial aspect of the thigh and the hip adductor muscles.

The superior hypogastric plexus provides sympathetic innervation to the pelvis, while the inferior hypogastric plexus contains both parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers. The pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-S4) provide parasympathetic innervation to pelvic organs. Parasympathetic output causes gastrointestinal peristalsis and contracts muscles for defecation and urination. It is also involved in the engorgement of erectile tissue. Sympathetic output acts antagonistically to the parasympathetic output and is involved in muscle contraction during orgasm.

Muscles

The muscles of the pelvis can be divided into 3 groups. Some muscles attach to the trunk and provide postural support. Other muscles attach to the hip and thigh and allow for movement. Finally, the muscles of the pelvic floor and perineum are involved in support of the pelvic floor as well as urogenital and gastrointestinal functions. [5][6]

The iliopsoas muscle attaches the spine to the pelvis at the iliac fossa and the spine to the femur at the lesser trochanter. It flexes the hip, which is the action performed during a “sit-up.” The gluteus maximus muscle is the primary hip extensor and composes most of the mass of the buttocks. It originates at the ilium and sacrum and attaches to the gluteal tuberosity of the femur as well as the iliotibial band. The iliotibial band is a band of connective tissue on the lateral thigh running from the iliac crest to the proximal anterolateral tibia. The gluteus medius, located deep to the gluteus maximus, runs from the ilium to the greater trochanter of the femur. It serves to externally rotate and abduct the hip as well as balance the pelvis during ambulation. Weakness of this muscle, as can be found with superior gluteal nerve injuries, will result in a Trendelenburg gait, where the contralateral hip drops while walking. Like the gluteus maximus, it also attaches to the iliotibial band. The superior portion of the iliotibial band blends with the muscle fibers of the tensor fascia lata, which aids with stabilization and hip abduction. This “IT” band can be a source of discomfort for runners, known as iliotibial band syndrome.[7] The gluteus minimus is located just inferior to the gluteus medius. It also runs from the ilium to the greater trochanter of the femur and assists the gluteus medius to abduct the hip.

Another group of six muscles works to externally rotate the hip: the piriformis, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, obturator internus, obturator externus, and quadratus femoris. Due to their shared function, this group of muscles is known as the lateral rotator group. The piriformis originates on the sacrum and inserts on the greater trochanter. The gemellus (Latin for “twin”) superior and inferior muscles originate on the ischium and insert indirectly onto the greater trochanter by blending with the tendon of the obturator internus originating from the obturator membrane. The obturator externus also functions as a hip adductor and originates on the ischiopubic ramus and inserts into the trochanteric fossa. Finally, the quadratus femoris originates on the ischium and inserts on the intertrochanteric crest.

Other muscles assisting with external rotation outside of these include the lower fibers of the gluteus maximus, the gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus when the hip is extended (if flexed they internally rotate the hip,) the psoas, and sartorius muscles. The sartorius originates on the anterior superior iliac spine and inserts on the pes anserinus in the tibia. It has four functions: flexion, abduction, and lateral rotation of the hip as well as flexion of the knee. The name comes from the Latin word for tailor, and all four actions can be performed to look at the sole of one’s shoe.

The hip adductors are large muscles on the medial thigh that adduct the leg and share a common innervation in the obturator nerve. They include the adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, pectineus, and obturator externus muscles. The adductor longus, brevis, and magnus muscles originate on the pubic bone and insert on the linea aspera of the femur. The adductor magnus also has some fibers originating on the ischial tuberosity and additional insertions on the adductor tubercle, as well as some innervation from the tibial nerve. The gracilis originates on the pubic bone and inserts on the pes anserinus of the tibia along with the sartorius. The pectineus originates on the pectineal line of the pubic bone and inserts on the pectineal line of the femur. While it has occasional innervation from the obturator nerve, it commonly is innervated by the femoral nerve.

The hamstrings are a group of muscles on the posterior aspect of the thigh that flexes the leg composed of the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris. They originate on the ischial tuberosity and insert around the knee on the tibia and fibula. They are innervated by the tibial branch of the sciatic nerve. Occasionally, the adductor magnus is considered a hamstring as it shares many of these characteristics.

There are 3 layers of the pelvic floor musculature. From caudal (superficial) to cephalad (deep), they are the urogenital triangle, the urogenital diaphragm, and the pelvic diaphragm.

The urogenital triangle consists of several muscles. The superficial transverse perineal muscle originates at the ischial tuberosity and extends to the central tendinous perineal body, which lies immediately ventral to the anus. It is involved primarily with the support of the pelvic floor. The ischiocavernosus muscle extends from the ischial tuberosity to the ischiopubic rami and is involved in supporting the erect male penis, the female vagina, as well as flexing the anus. The bulbocavernosus (bulbospongiosus in men) muscle is located in the midline of the pelvis and describes a dorsal to ventral path starting at the tendinous body and coursing to the ischiocavernosus and contributes to erections. In females, the fibers are divided and course laterally around the vaginal introitus. The final muscle in the urogenital triangle is the anal sphincter. It is attached to the dorsal central tendinous end of the perineal body and its fibers spread to the levator ani posteriorly. This muscle regulates defecation.

Deeper (more cephalad) into the pelvis is the urogenital diaphragm. It is a triangular ligament with a strong muscular component that stretches from the pubic symphysis to the ischial tuberosities. It occupies the ventral side of the pelvic outlet and is composed of several muscles. The urethral sphincter is an autonomic smooth muscle internal sphincter located at the urethro-vesicular junction. In males, the external sphincter is located just caudal to the prostate, and in females, it is located just caudal to the internal sphincter. The external sphincter is skeletal muscle and is under voluntary control. Both the internal and external sphincters are involved in regulating urination. The deep transverse perineal muscle extends from the inferior rami of the ischium and inserts into the tendinous median plane and aids in the support of the pelvis. The caudal and cephalad borders of this muscular-tendinous plane are embedded in a layer of fascia. The caudal layer of fascia is known as the perineal membrane.

The third, most cephalad (deep) layer is the pelvic diaphragm, a thin and muscular layer that extends from the pubic ramus to the coccyx and inserts laterally into the arcus tendinous fascia, a condensation of the membrane of the obturator internus muscle. It is a funnel-shaped sling and represents the inferior (caudal) border of the internal pelvic cavity. The diaphragm is composed of several muscles and endopelvic fascia, the largest of which is the levator ani muscle. This muscle is composed of 3 parts: the puborectalis muscle, pubococcygeus muscle, and the iliococcygeus muscle. The levator ani's ventral border is the posterior surface of the superior pubic rami. It courses bilaterally around the pelvis and inserts at the arcus tendinous fascia. Between the left and right levator pass the urethra, anal canal, and vagina in females.

Physiologic Variants

The most significant physiologic variants of the pelvis are relevant to child-bearing. There are 4 recognized variants of the pelvis as classified by the "Caldwell-Moloy" system. [8]

Gynecoid

This is the classic female pelvis found in roughly half of women. The inlet is ovoid to almost circular. The pubic arch and pelvic outlet are wide. The sacrum is deeply curved, and the ischial spines are relatively blunt. Overall, the internal dimensions of this pelvic type are the largest and most conducive to childbirth.

Android

This is the classical male pelvis, although it is present in approximately 20% of women. The inlet is heart-shaped, and the sidewalls are convergent. The sacral curve is shallow. Overall, internal dimensions are smaller than those of the gynecoid pelvis, and childbirth can be complicated due to this shape.

Anthropoid

Common in men and present in approximately 25% of women. It has an ovoid inlet and is greater in dimension from front to rear than side to side. The pubic angle is somewhat less than the gynecoid but greater than the android pelvis. This pelvis is generally considered suitable for childbirth.

Platypelloid

A very wide and shallow inlet is the hallmark of this pelvis. It is present in approximately 5% of women. This pelvis is commonly associated with a high transverse arrest of labor due to the inability of the fetal head to navigate the inlet secondary to insufficient space in the anterior to posterior dimension. Uncomplicated vaginal birth is very uncommon with this pelvis.

The body assists childbirth with any type of pelvis through the hormone relaxin, which is released by the placenta and causes the ligaments that bind the pubic bones to become more pliable. This allows the pelvis to enlarge by facilitating motion at the pubic symphysis. This increased laxity can be a source of pain in late pregnancy.

Surgical Considerations

Trauma to the pelvis has a high mortality rate, as bleeding both from associated vessels, such as the pre-sacral venous plexus, and the pelvis itself commonly leads to acute hemorrhagic shock. For this reason, the initial assessment in trauma bays often involves examining the integrity of the pelvis through compression and digital rectal exam, followed by an AP pelvic x-ray. “Open book” fractures occur when sufficient trauma breaks the pelvic ring in two or more locations.[9]

Acetabular fractures can involve the anterior column, posterior column, or both, and the specific classification of fracture is assessed with Judet views on x-ray.[10] The anterior column is also known as the iliopubic column, as it is comprised primarily of these bones along with the anterior wall of the acetabulum. The posterior column involves the ischium, sciatic notches, and posterior wall of the acetabulum. The posterior wall is most likely to be injured in high energy trauma due to force being transmitted up the femur in situations like motor vehicle accidents. Acetabular fractures can present with hip dislocation, especially posterior wall fractures with posterior dislocation following a “dashboard” injury when the flexed hip is struck at the knee against the dashboard of a vehicle in a collision. Posterior dislocations resulting from these injuries present with limb length discrepancy, adduction, internal rotation, and flexion. Conversely, anterior hip dislocations are much less common and present in extension and external rotation.

The ureters enter the pelvic brim over the bifurcation of the common iliac arteries into the internal and external branches. The course of the ureter may be identified by watching for the peristaltic motion and tracing it down to the lower pelvis, where it passes under the uterine artery in females. This relationship can be remembered by the mnemonic “water under the bridge,” where the ureter is water and the uterine artery is the bridge. This way, a surgeon may ensure that he or she is working safely away from it during pelvic surgery. Additionally, the ureters course approximately 2 cm from the cervix at the level of the uterine artery. One study showed that in 15% of women, that distance is less than 5 mm. This may explain the observed incidence of ureteral ligation during hysterectomy. [11]

Clinical Significance

Many pelvic landmarks are easily palpable on physical exam including the iliac crest, the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), and the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS.) As such, these landmarks have become instrumental in physical examinations by allowing practitioners to quickly and simply identify internal anatomy based on its relation to superficial anatomy for both diagnostic and therapeutic measures.

The iliac crest is the most superior part of the pelvis located near what is commonly referred to as the waist. This level corresponds to around L3-L4 lumbar vertebrae and can be used to safely place a lumbar puncture needle by minimizing the potential for spinal cord damage while still accessing cerebrospinal fluid, as the cord itself ends around the L1 vertebral level.

The ASIS is the most anterior portion of the iliac crest and is the attachment point for the sartorius muscle as well as the inguinal ligament which connects to the pubic tubercle. This point finds its use in the evaluation of appendicitis, as McBurney’s point of the appendix is defined as one-third the distance from the ASIS to the umbilicus. The ASIS also becomes helpful in identifying leg length discrepancies, as pelvic rotation often accommodates these differences while standing and walking. Therefore, leg length is measured from the ASIS to the medial malleolus.[12]

The PSIS marks the posterior edge of the iliac crest and manifests in some individuals as dimples on the lower back, colloquially called “dimples of Venus.” This landmark is useful for identifying the sacroiliac joint, and tenderness over this joint can be a symptom of sacroiliitis, a condition present in some inflammatory spondyloarthropathies.

In developmental dysplasia of the hip, the acetabulum is not properly formed to hold the head of the femur. This condition is associated with breech presentation in labor. To assess for this disorder there are two physical exam maneuvers: Ortolani and Barlow. With the Barlow maneuver pressure is applied posteriorly with an adducted and flexed hip to assess for dislocation, while the Ortolani maneuver involves relocation with hip abduction and anterior force.[13]