Introduction

The neonatal period is the period of the most dramatic physiologic changes that occur during human life. While the respiratory and cardiovascular systems change immediately at birth, other organ systems evolve slowly with time until the transition from intrauterine to adult physiology is complete. The transitional period of the newborn is a critical time for humans to adapt to life outside the womb. There are distinct physiologic changes during this period, especially regarding the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The loss of the low-pressure placenta and its ability to facilitate gas exchange, circulation, and waste management for the fetus creates a need for physiologic adaptation.

Premature birth can significantly thwart these physiologic changes from occurring as they should. The endocrine system, specifically the release of cortisol via the hypothalamus, is responsible for lung maturation of the fetus and the neonate. There is a “cortisol surge” that begins with cortisol levels of 5 to 10 mcg/ml at 30 weeks gestational age, 20 mcg/ml at 36 weeks, 46 mcg/ml at 40 weeks, and 200mcg/ml during labor.[1] Cortisol is responsible for lung maturation, thyroid hormone secretion, hepatic gluconeogenesis, catecholamine secretion, and the production of digestive enzymes. Mature thyroid function appears to help prepare the neonatal cardiovascular system and aid in the regulation of temperature.

Following clamping of the umbilical cord and the first breath of life, arterial oxygen tension increases, and pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, facilitating gas exchange in the lungs. Subsequent pulmonary blood flow will cause an increase in left atrial pressure and a reduction in right atrial pressure. Changes in the PO2, PCO2, and pH are contributing factors to these physiologic changes in the newborn. Lung surfactant plays a critical role in these changes allowing the lungs to mature upon delivery. Remnants of fetal circulation (ductus arteriosus, foramen ovale, ductus venosus) will also gradually recede during this neonatal period, defined as up to 44 weeks postconceptual age.

Organ Systems Involved

Cardiovascular System

Separation from the placenta causes a change in significant vascular pressures in the neonate. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) decreases with increased blood oxygen content, while the systemic vascular resistance (SVR) increases due to the loss of the low-pressure placenta. The neonatal heart has a decreased number of myocytes, is more fibrous, and lacks the compliance of its adult counterpart; therefore, it must rely on the flux of ionized calcium into the sarcoplasmic reticulum for contractility. Cardiac output is dependent on heart rate as the neonate is unable to generate increases in stroke volumes due to their non-compliant ventricle. There is a dominant parasympathetic tone with the increased presence of cholinergic receptors causing a bradycardic response to stress. A striking difference between adult and neonatal physiology is that adults have a dominant sympathetic tone, generating tachycardia to their stress response. Due to the neonate's dependence on heart rate for cardiac output, bradycardia can result in decreased blood pressure and eventual cardiovascular collapse, so low or falling heart rates require prompt attention. Additionally, there is a delay in diastolic relaxation and subsequent decreased diastolic filling, making neonates unable to manage increased circulating volumes.

At birth, the exposure to increased oxygen and a decreasing level of prostaglandins precipitate the closure of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), a remnant of fetal circulation, thereby allowing more blood to circulate to the lungs. Complete closure typically occurs throughout the 2 to 3 weeks following birth. If the communication fails to close between the descending thoracic aorta and pulmonary artery within the expected period, a left-to-right shunt develops. PDA is considered an acyanotic congenital heart defect, and it can be closed surgically with a PDA ligation. This procedure is regarded as a preferred method over pharmacologic management (usually indomethacin) as the latter can be ineffective, have a poorly tolerated side effect profile, or enable recurrence.[2] The patent foramen ovale (PFO) allows fetal blood to pass from the right to the left atrium and bypass the right ventricle allowing the most oxygenated blood to go to the brain. The PFO will start to close with the increase in left atrial pressures, and the lack of blood flow will cause involution of the structure but will not completely close until approximately one year of age. The ductus venosus is a connection from the umbilical vein to the inferior vena cava, which shunts blood past the liver. The ductus venosus typically closes within 3 to 7 days after birth as a result of the decrease in circulating prostaglandins. If this shunt remains patent, there will be an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt allowing the toxins in the blood to circumvent the liver, which, in turn, will produce an increase in substances like ammonia and uric acid and would necessitate surgical intervention. With the closure of the ducts (PDA, PFO), the circulation changes from parallel to series.

Respiratory System

The neonate possesses some physical characteristics which can inhibit efficient breathing mechanics. They have very cartilaginous rib cages with a horizontal rib arrangement and decreased lung compliance contributing to paradoxical chest movements. They are susceptible to oxygen desaturations as they have reduced functional residual capacity (FRC), higher minute ventilation to FRC ratios, and consume almost twice as much oxygen as adults. Closing volume is greater than the FRC in neonates, and therefore small airways can close during expiration limiting gas exchange. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can be useful in term and preterm infants to help maintain lung volumes during spontaneous respiration.[3] They are more subject to respiratory fatigue second to a more substantial proportion of Type I diaphragmatic muscle ("slow-twitch") fibers.

The neonatal respiratory system has more dead space (which does not participate in gas exchange) compared to an adult, as well as fewer alveoli, which are thicker and less efficient in gas exchange. Neonates are obligate nose breathers and have narrow nasal passages, which account for a baseline airway resistance they must overcome. There are also significant differences in the neonatal airway; the newborn infant has a large head and short neck relative to body size. Some of the airway characteristics that make neonatal intubation more challenging include a large tongue, long, floppy omega-shaped epiglottis, larger arytenoids, and narrow glottis. The cricoid cartilage below the glottis is narrower than the glottis making the subglottic area the narrowest portion of the airway and giving it a characteristic "conical" shape. The larynx is more cephalad and anterior in the C3-C4 position compared to the adult (C5-C6).

These anatomical airway differences allow for the neonate to suckle effectively by allowing an open channel for nasal breathing created by the approximation of the epiglottis and the soft palate while the milk passes over the back of the tongue to the side of the epiglottis. This accommodation allows for simultaneous nasal breathing while feeding. The cartilage in the airway is more collapsible, and the underlying tissue is loose, making the neonatal airway more vulnerable to edema.

Hematologic System

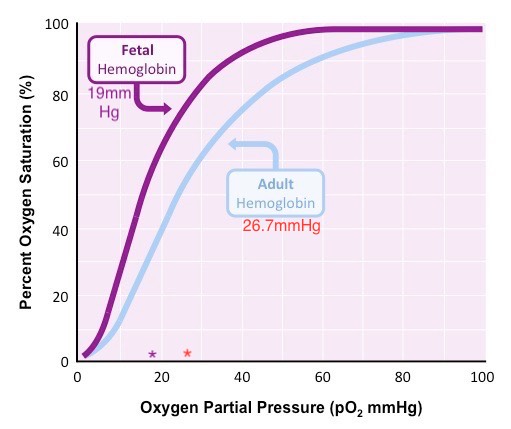

Neonates are born with fetal hemoglobin (HbF), which comprises 70 to 90% of the hemoglobin molecules and remains present in circulation until about three months of age when it becomes gradually replaced with adult hemoglobin (HbA). HbF has a high affinity for oxygen, causing the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve to shift to the left. Therefore, arterial oxygen pressures are lower in the neonate than in the adult. The partial pressure of oxygen at which hemoglobin is 50% saturated with bound oxygen is 19mmHg for newborns vs. 27mmHg for adults (see Figure 1). 2,3-Bisphosphoglyceric acid (2,3 BPG) binds less strongly to fetal hemoglobin, also contributing to this left shift. HbF also can also protect the sickling of red blood cells. The normal neonatal hemoglobin level is 18 to 20 gm/dL. Due to the immature liver in the newborn, vitamin K clotting factors are deficient (II, VII, IX & X) for the first few months of life. Vitamin K is administered in the delivery room to prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn.

Central Nervous System

The neonatal brain lacks cerebral autoregulation, a protective mechanism that controls blood perfusion of the brain under the circumstances of extreme blood pressures. In the setting of elevated blood pressure, the neonate is predisposed to an intraventricular hemorrhage as fragile blood vessels can rupture. This arrangement also allows the maintenance of cerebral perfusion in the setting of hypotension. In adults, cerebral autoregulation occurs in the range of 60 to 160 mmHg mean arterial pressure (MAP). The lower limit of neonatal autoregulation is at 30mmHg, although the upper limit is undetermined.[4] The blood-brain barrier is immature and weak, allowing medications to more easily permeate the central nervous system and therefore exhibit increased sensitivity to lipid-soluble drugs. The spinal cord extends to L3, two segments below where the adult cord ends. In the neonate, the dural sac ends at S4 as compared to S2 in an adult. Additionally, neonates also have an increased amount of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and immature myelination, which can shorten and decrease the potency of local anesthetics in the CSF.

Endocrine System

Neonates have an increased body surface area to weight ratio subjecting them to losing body heat more readily. They have a poor compensatory mechanism to prevent heat loss as they are unable to shiver or utilize vasoconstrictive mechanisms. They are born with brown fat, which allows non-shivering thermogenesis, an oxygen-consuming process. Hypothermia should be avoided in newborns as it induces a stress response, which causes a cascade of events to occur, including increased oxygen demand, pulmonary vasoconstriction, metabolic acidosis with peripheral vasoconstriction, and tissue hypoxia. Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common pre-existing medical conditions associated with an increased risk of pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes.[5] Maternal type I diabetes is associated with fetal growth restrictions and small-for-gestational-age pregnancies. Maternal type II diabetes is associated with insulin resistance, in which increased levels of glucose to the fetus can result in fetal macrosomia. There is a surge of thyroid stimulation hormone (TSH) immediately after birth, causing an increase in the release of T4 and T3. The presence of TSH is essential for the development of appropriate neurologic function and growth in the newborn. Thyroid function is part of the newborn screen, and the clinician can address deficiencies with supplementation.[6]

Gastrointestinal / Hepatic System

Neonates have a decreased gastric emptying time and have decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone causing more gastroesophageal reflux. Hypertonic feeds increase intestinal energy demands resulting in bowel ischemia and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). Immature hepatic function and decreased hepatic blood flow result in delayed drug metabolism. Plasma protein synthesis begins to increase after birth and is essential to the formation of albumin and alpha-fetoprotein.[7] Immaturity of hepatic function in the neonate affects glucose levels. Glycogen storage occurs in late gestation but is not yet sufficient to help the neonate in times of prolonged fasting; therefore, supplemental glucose infusions are required during these periods at a rate of 5 to 8 mg/kg/min to prevent hypoglycemia.[8] Physiologic jaundice is a self-limiting process that can be present in the neonate secondary to increased unconjugated bilirubin. The cytochrome p450 enzymes are only at 30% of adult levels at birth, which results in prolonged elimination of various medications.

Renal System

The fetal kidney can produce urine starting at the 16th week of gestation, and nephrogenesis is complete at 34 to 36 weeks. At birth, there is a decrease in renal vascular resistance as the mean arterial blood pressure increases. Initially, only 3 to 7% of the cardiac output is dedicated to renal blood flow (RBF) but will continue to increase to 10% after the first week of life.[9] The neonatal kidney is not able to concentrate urine due to the lack of development of the kidney's tubular function leading to high urine output initially. This increase in urine output in the first few days of life causes a decrease in total body water (TBW), reflecting a reduction in the newborn's body weight.[10] By the 5th to 7th day of life, kidney function starts to stabilize. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is only 20 to 30% that of an adult, and therefore the neonate is subject to prolonged effects of renally excreted medications. An increased volume of distribution necessitates higher weight-based medication dosages in neonates. However, this initial increase in medication can be offset by the fact that drugs will take longer to be excreted by the kidney; therefore, the dosing interval should increase to account for this. Low RBF and GFR cause neonates to have difficulty with increased fluid volumes, so administering intravenous fluids should always be based on body weight and clinical assessment. Due to their large body surface area, neonates are subject to greater insensible fluid losses.