Introduction

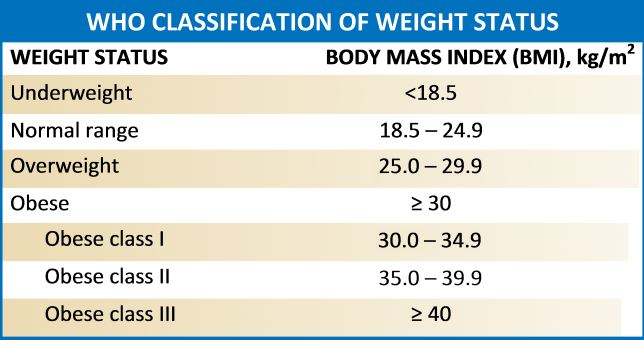

Obesity refers to abnormal or excess body weight (mainly fat) concerning height. It is a growing health problem in the United States as well as around the globe with a significant economic burden. More than a third of individuals in the USA have a body mass index (BMI) of over 30kg/m^2, and the cost for obesity has risen to $147 billion annually. It is also associated with various comorbidities, which include type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart diseases, stroke, obstructive sleep apnea, Hypogonadism, and premature death. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2015-2016 data), approximately 93.3 million US adults were obese.[1][2] A similar trend is on the rise in many other western countries.

Function

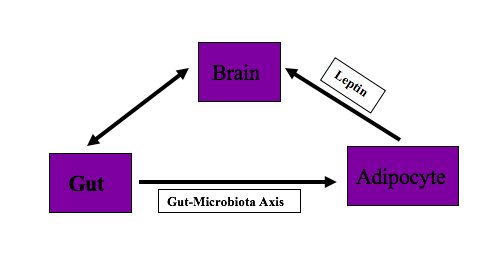

The body has been designed to balance energy homeostasis for survival. To maintain energy homeostasis, various body organs interact with each other. Brain, gut, and adipocytes play an essential role in supporting the efficient and controlled supply of energy to the body and maintaining this energy homeostasis. The diaphony among these organs is responsible for maintaining body fat. The dysregulation in the communication of these brain, gut, and adipocytes, can lead to the accumulation of excess body weight relative to height. If the body weight leads to a BMI of 30kg/m^2 or above, a person is called obese. This article provides an overview of the brain, gut, and adipocyte interaction and imbalance or miscommunication between these organs. Understanding this interaction will help the clinician to diagnose and counsel patients on controlling their diet and prescribing appropriate treatment measures to patients.

Role of brain in energy homeostasis:

The brain plays a pivotal role in maintaining energy homeostasis. To ensure energy balance, the brain adjusts the behavior of the body based on continuous monitoring of systemic metabolic state. If the body is deficient in energy, the brain sends signals to alter food intake as well as adjusts physiological functions such as adiposity, thermogenesis, and hepatic glucose production. Arcuate nucleus and ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) in forebrain and nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS)-dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) complex in the hindbrain, are responsible for metabolic feedback from the gastrointestinal tract and adipose tissues. These brain areas express receptors for gut hormones and adipokines.[3][4]

The primary center in the brain which is responsible for controlling appetite is the hypothalamus. Feeding centers are located in the lateral hypothalamus, whereas satiety centers in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Hypothalamus monitors appetite and metabolism by detecting circulation hormones from the gut and adipose tissue. These hormones interact with hypothalamic nuclei through circumventricular organs (CVO), which lack blood-brain barriers.[5]

The brain stem also participates in the regulation of appetite centers. With gut distension, gut hormones and chemical stimuli are produced and stimulate the vagal nerve. The vagus nerve transmits information to the brain stem.[6]

The central nervous system produces orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) and anorectic (appetite suppressing) neuropeptide. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is an orexigenic neuropeptide, and Proopiomelanocortin (POMC), cocaine, and amphetamine-regulated transcripts (CART) are anorectic neuropeptides.

In the nervous system, NPY is the most abundant peptide. It causes increased food intake, preferably carbohydrate-rich food, and reduce energy expenditure and thermogenesis. NPY expression increase with fasting and decrease with food consumption.[7]

POMC converts to alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH), which stimulates melanocortin receptors, MC3R, and MC4R. MC3R and MC4R are called neural melanocortin receptors that control satiety and energy expenditure. MC4R mutation has been studied to be associated with polygenic obesity.[8]

The role of the hypothalamus in controlling appetite is not fully understood. Some scientist believes that cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and limbic system are reward pathway that may be responsible for over-riding the weight regulation system, causing obesity and overweight.

Role of the gut in energy homeostasis:

The gut is responsible for energy intake. It communicates with the brain through hormonal and neural pathways. With food consumption, the gut secretes several peptides of which peptide YY (PYY), cholecystokinin (CCK), and glucagon-like peptides-1(GLP-1) provide feedback to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) via stimulating the vagal nerve. The arcuate nucleus in the forebrain and nucleus tractus solitarius of the hindbrain are two areas of the brain which are targeted by gut hormones. These brain areas relay the information to the paraventricular nucleus (PVH) of the hypothalamus and suprachiasmatic nuclei, which are critical regulatory areas of metabolic homeostasis. Paraventricular nucleus modulates autonomic output, and neuroendocrine hormones and supraventricular nuclei balance sympathetic and parasympathetic output to synchronize behavior and physiology of the whole body.[9]

Autonomic control of the gut is also responsible for tuning energy production and expenditure. The parasympathetic outflow is the connection between hypothalamic insulin and liver glucose production, as well as brain glucose and circulating triglyceride. Sympathetic nervous system activation inhibits the sensitivity of peripheral insulin, stimulates glucose production via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Neuroendocrine hormones (e.g., epinephrine, glucocorticosteroids, growth hormones, and thyroid hormones), which hinders insulin action on the liver, are also influenced by feedback from gut hormones to hypothalamic autonomic control.[10]

The gut interacts with adipose tissue via hormones and gastrointestinal related factors, e.g., bile acids. Anorexigenic gut hormones activate brown adipose tissue, whereas orexigenic hormones prevent brown adipose tissue activity. Change in gut hormones with food intake affects brown adipose tissue.[4]

Role of the adipose tissue in energy homeostasis:

Adipose tissues balance energy and regulate long term body weight. They communicate with the brain through adipokine, which includes leptin, adiponectin, apelin, and resistin and neuronal inputs. Brown adipose tissue is involved in energy balance.[11]

Leptin is the hormone that is secreted by adipocytes. Leptin secretion from adipocyte is in proportion to body fat and used as sensing signals for energy production and consumption by CNS. Leptin suppresses food intake. In the absence of leptin or leptin deficiency or its resistance, the hypothalamus perceives decrease body fat stores and stimulates appetite centers, which cause hyperphagia and hyperglycemia. Therefore, the lack of leptin or defective leptin receptors can lead to obesity.[12]

Gut interacts with adipocytes via the microbiota-fat-signaling axis. Microbes in the gut participate in adipogenesis. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by gut microbiota inhibits lipolysis and promotes differentiation of adipocytes. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which are the component of gut microbiota, cause inflammation, and immune-cell infiltration in adipose tissue. Disruption of gut microbiota accelerates adipogenesis leading to obesity.[13]

The sympathetic nervous system stimulates lipolysis and mobilizes lipids from white adipose tissues by releasing epinephrine. These sympathetic neurons become stimulated by higher autonomic centers in the PVH or the lower centers in the hindbrain or the spinal cord.

Issues of Concern

The balanced interaction of brain-gut and adipocyte plays an essential role in maintaining appropriate energy balance, body fat, and weight. Miscommunication between these organs can lead to an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, which leads to obesity. These are the following mechanisms through which the brain, gut, and adipocyte miscommunication lead to obesity:[14][15]

1) Weakened or defective signals from the brain in response to nutrients and satiety cause disinhibition of liver glucose production and unbalanced or over-feeding.

2) Lack of inhibition of neuropeptide Y neurons in the hypothalamus, dysregulation of melanocortin receptors in the forebrain and hindbrain, and overactivation of orexin receptors due to sleep deprivation leads to abnormal activation of sympathetic neurons and decrease the sensitivity of insulin which leads to obesity.

3) Leptin resistance in the hindbrain and hypothalamus can also lead to obesity. The brain perceives leptin resistance as lower long term energy stores, and as a result, it increases extra energy intake, i.e., overfeeding (hyperphagia) and obesity. Leptin resistance can be central or peripheral.

Causes of central leptin resistance include[12]:

- The mutation on the leptin receptor located in the brain and various other tissues - mutations in receptors lead to impaired signaling in response to leptin

- Decreased leptin transport across blood-brain barriers due to high triglyceride levels

- Decreased leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier due to ObR receptor saturation or downregulation

- Reduced sensitivity of ObR due to excessively high levels of leptin

- Increased expression of SOCS3 and PTP1B - inhibitors of leptin signaling- cause leptin resistance

- Increased leptin binding protein levels

Causes of peripheral leptin resistance include:

Leptin resistance in peripheral organs, e.g., in the liver, heart, and skeletal muscles, are not well studied. According to some studies, leptin resistance in peripheral organs might be due to reduced activation of signaling protein or increased production of leptin signaling inhibitors.

4) Brain trauma

5) Brain surgery of craniopharyngioma

6) Inflammatory lesions of the hypothalamus

7) Psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety

8) Sleep deprivation causes abnormal elevation of sympathetic outflow and overactivation of orexin neurons

9) Genetic mutations in receptors or hormones and neurochemicals. (Pro-opiomelanocortin gene mutation)

10) Microbial dysbiosis due to a high-fat diet

11) Decreased intestinal barrier functions

12) Inflammation of gut due to a high-fat diet

13) Metabolic endotoxemia

14) Chronic low-grade systemic inflammation

15) Desensitization of vagal afferent nerves

Clinical Significance

Comprehending the interaction between the brain, gut, and adipocytes is very important in identifying the main reason and providing appropriate management. Some of the uncommon disorders that occur due to improper interaction of brain, gut, and adipocyte interaction are:

- Hypothalamic obesity due to injury to the paraventricular and ventromedial region of the hypothalamus. Damage to these regions causes hyperphagia, which leads to obesity. It may occur due to tumor, trauma, or inflammatory diseases. Calorie restriction causes weight gain in these patients, and lifestyle modification is useless. Pharmacologic treatment includes octreotide to suppress insulin secretion or adrenergic to mimic sympathetic activities.[16][17]

- Sleep deprivation correlated with an increase in serum orexigenic hormones (e.g., ghrelin), a decrease in anorexigenic hormones (e.g., leptin), and increase hunger and appetite for carbohydrate-rich foods.[18][19]

- Antibiotic use in early life can lead to obesity in later part of life. Specific alteration in the composition and function of the human gut microbiome can affect weight. Obesity due to alteration in the gut microbiome can have treatment with prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, or even fecal transplant.[20]

- Obesity due to central or peripheral leptin resistance requires treatment with leptin based therapies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team that includes a nurse, or nurse practitioner, a physician, an exercise psychologist, a dietician, and a psychotherapist, plays a vital role in reducing patient weight and maintain it.[21] [22] The imbalance and miscommunication between the brain, gut, and adipocytes entail different pathology of obesity. Hence, weight gain due to the mentioned miscommunication should be managed with a combination of increased physical activity, dietary changes as well as behavioral modifications.

In order to improve health care outcomes for obesity, the following points can be followed regardless of the type and cause of obesity.

1) A thorough history and physical examination prove helpful to identify common as well as rare causes of obesity( for example, leptin resistance).

2) Obesity due to the above-mentioned causes should be addressed, and appropriate counseling and treatment should be prescribed (for example, leptin resistance should be treated with recombinant leptin).

3) Clinicians should remain up-to-date with the obesity management guidelines. Specialized training in obesity management should be provided to physicians, and training should start at the medical school levels. Continue medical education (CME)-based activities also raise awareness of obesity and its management among doctors. Specialist training programs are available, which should be utilized by doctors.

4) Clinicians should communicate empathetically and in a non-judgmental way to patients regarding obesity and its management. The healthcare team should ask permission from the patient to discuss the topic of weight. Appropriate words should be used. Weight and BMI should be used instead of heaviness, fatness, and large size. Safe phrases for addressing patients with obesity include

- How do you feel about your weight?

- Do you observe your weight?

- When did you last weigh yourself?

- Has anyone told you the side effects of extra weight?

- Have you noticed any change in your weight over the last few months?

5) In managing patients with obesity, the viewpoint of the patient should be given consideration, and physicians should tailor their advice for individual patients.

6) Effective support for obesity management and behavioral change should be considered. The "five As" of obesity counseling would be very helpful.

- Ask permission to initiate conversation.

- Assess BMI, waist, and obesity stage, explore drivers of excess weight and complications.

- Advice on the adverse health risk of obesity.

- Agree on realistic weight loss expectations and targets, behavioral changes, and specific details of the treatment options.

- Assist in identifying and addressing barriers, provide resources and assist in identifying and counseling with appropriate providers

7) Appropriate counseling is positively associated with weight loss. Studies have shown that individuals who receive weight-loss counseling from their primary care doctors are more likely to pursue weight loss than those who do not receive counseling. Clinicians should counsel patients to change multicomponent, which include increasing physical activity, improving eating behavior and quality of diet, and reduce energy intake. The patient should also be counseled for self-monitoring of calorie intake, goal setting, and stimulus control.

8) Clinicians should offer the opportunity of a follow-up visit if any patient is not ready to discuss weight loss at the moment.