Introduction

The pharynx is a conductive structure located in the midline of the neck. It is the main structure, in addition to the oral cavity, shared by two organ systems, i.e., the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and the respiratory system. It is funnel-shaped with its upper end being wider and located just below the lower surface of the skull, and its lower end is narrower and located at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra (C6) where the commencement of the esophagus posteriorly and the larynx anteriorly takes place. Its muscular-membranous integrity allows it to mediate several vital functions related to either organ system, e.g., food swallowing, air conduction, and voice production. Knowing its structure and function, embryology, neurovascular supply, musculature, surgical implications, and clinical significance will permit us to comprehend its importance.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

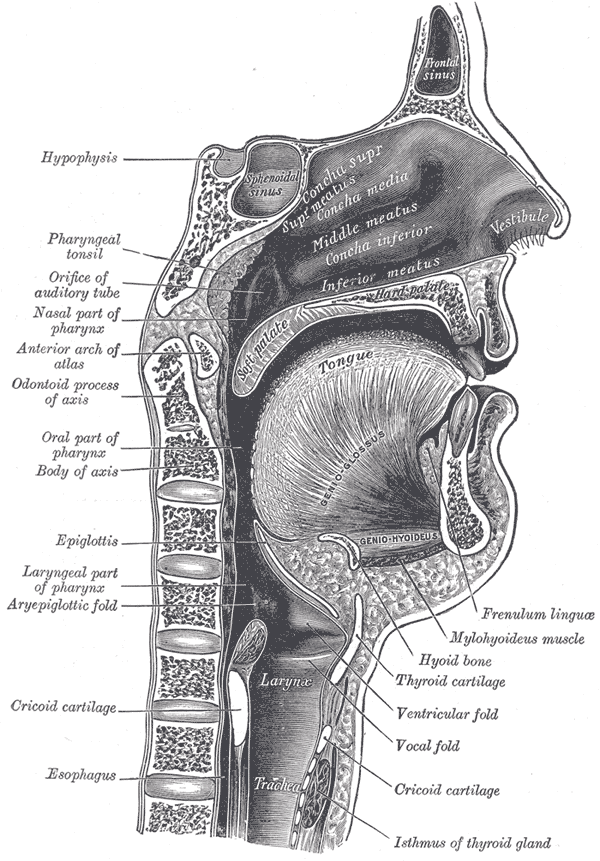

Regionally, the pharynx divides into three parts which are from superior to inferior:-the nasal pharynx, located behind the posterior nasal apertures (choanae), the oral pharynx, located behind the opening of the oral cavity, and the laryngeal pharynx, located behind the inlet (opening) of the larynx. First, the nasal pharynx is only related to the respiratory tract as air passes through it from the nasal cavities. Also, within the lateral surface of the back of the nasopharynx, there are two openings, one on either side, which is called the auditory tubes (Eustachian tubes or pharyngotympanic tubes) surrounded by elevations of mucous membrane called tubal elevations. These tubes are connected to the middle ears (tympanic cavities) posteriorly and mainly serve to equalize pressure and facilitate the drainage of the secretions of the middle ears. Second, the oral pharynx is a continuation of the oral cavity and functions to pass the bolus toward the laryngeal pharynx below.

As the bolus passes from the oral cavity, the muscles of the soft palate contract to close the choanae so that food does not enter the nasal cavity. Simultaneously, the epiglottis (single cartilage at the upper part of the larynx) is pushed anteriorly to close the laryngeal inlet preventing food from entering the airways. Lastly, the laryngeal pharynx receives bolus from the oral pharynx and passes it into the esophagus for digestion. Air passes from the upper two parts of the pharynx (nasal and oral) and enters the laryngeal pharynx toward the inlet of the larynx and from there to trachea down the respiratory tract.[2][4][5][6]

Embryology

During the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation (development), on either side of the developing pharynx, the formation of the pharyngeal (branchial) apparatus takes place. The apparatus consists of arches, pouches, clefts, and membranes which contribute to the development of the head and neck. The whole pharynx develops from this apparatus, which is present on either side of the developing head. The musculature of the pharynx develops from three pharyngeal arches, i.e., the third, fourth, and sixth arches. The third pharyngeal arch gives rise to the stylopharyngeus muscle. However, the remaining muscles (constrictor and longitudinal groups) emerge from the fourth and sixth arches. The neurovascular bundles which pass through these arches also give off branches to supply the muscle(s) of each arch.[7][3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Four arteries from each external carotid artery supply the pharynx with oxygen-rich blood which is the ascending pharyngeal, tonsilar (a branch of the facial artery), maxillary and lingual arteries. Venous drainage is formed by the pharyngeal veins which drain the pharynx into the internal jugular vein. The lymphatic drainage of the pharynx is direct drainage, which means that lymph passes directly toward the deep cervical lymph nodes (DCLNs). The deep cervical lymph nodes are the groups of lymph nodes located along the course of the internal jaguar vein or indirect drainage toward the deep cervical lymph nodes via the retropharyngeal lymph nodes (located behind the pharynx) or paratracheal lymph nodes (alongside the course of the trachea).[3]

There is a ring of lymphoid tissue that is formed by four lymph groups, referred to as the Waldeyer ring. This ring protects the entrance of the GIT and the respiratory tract. It is formed superiorly by the pharyngeal tonsils, also known as adenoids, in the roof of the nasal pharynx. The palatine tonsils and tubal tonsils (around the auditory tubes) form the lateral wall of the ring. Inferiorly, the ring forms by the lingual tonsils on the posterior surface of the tongue.[8]

Nerves

The pharynx receives both sensory and motor nerve fibers. Sensory (afferent) fibers supply the mucous membrane of the three parts of pharynx and transmit common sensation (pain, temperature, pressure, and touch). The nasal pharynx receives nerve supply from the second division of the fifth cranial nerve (the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve or CN V2). The oral pharynx gets supplied by the ninth cranial nerve (the glossopharyngeal nerve or CN IX), and the laryngeal pharynx receives supply from the internal laryngeal nerve which is a branch of the superior laryngeal nerve of the tenth cranial nerve (the vagus nerve or CNX). The muscles of the pharynx receive motor (efferent) supply from the ninth and tenth cranial nerves. The stylopharyngeus muscle is the only muscle supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve. The vagus nerve supplies all other muscles, which will be listed later.[2][3]

Muscles

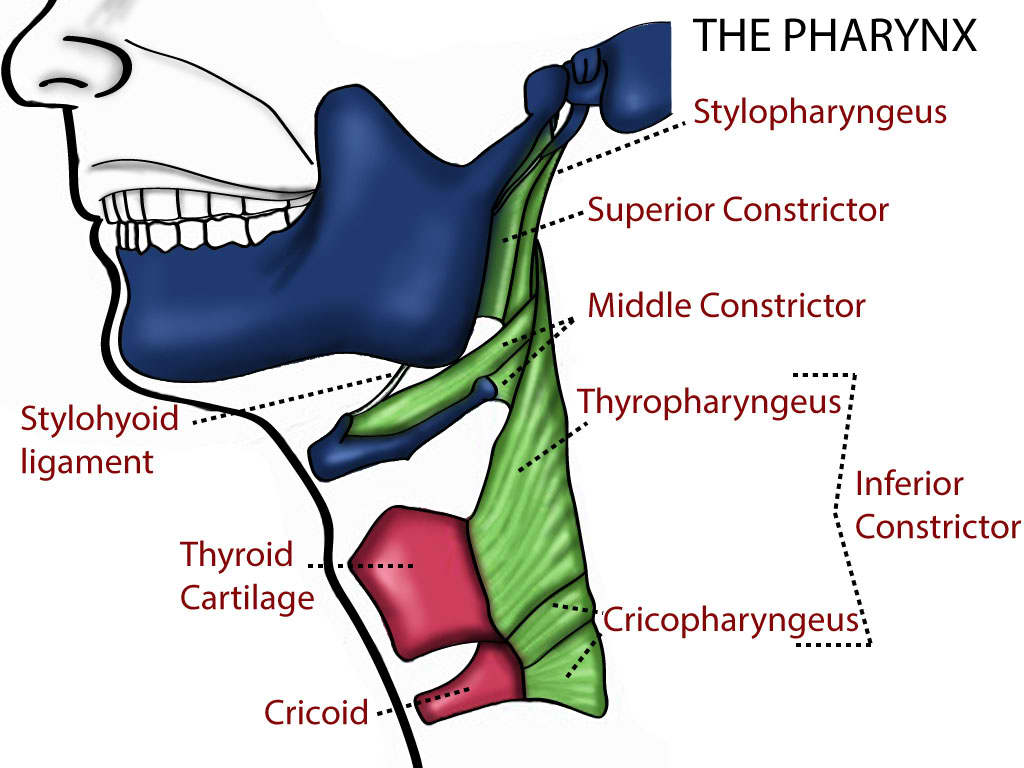

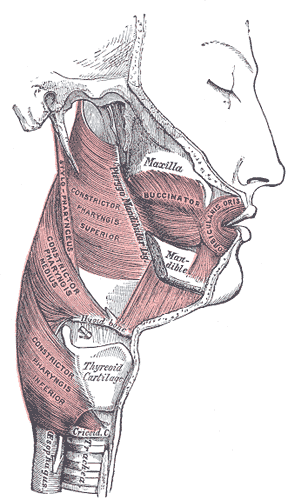

The musculature of the pharynx is extremely crucial for the pharynx to fulfill its various normal and necessary functions. Muscles of the pharynx, as has been noted earlier, can be described as four constrictor muscles (superior, middle, inferior and cricopharyngeus) and three muscles of the longitudinal group (stylopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, and salpingopharyngeus).[2]

The superior constrictor muscle originates from the medial pterygoid plate, pterygoid hamulus, pterygomandibular ligament and mylohyoid line of the mandible. It inserts into the pharyngeal tubercle of the occipital bone and the pharyngeal raphe (midline fibers) posteriorly. It aids in the closure of the soft palate during swallowing and most importantly is that it propels bolus toward downward.[2][5][9]

The middle constrictor muscle originates from the inferior portion of the stylohyoid ligament and the lesser and greater cornua of the hyoid bone. It inserts into the pharyngeal raphe and serves to propel bolus downward.[1][2]

The inferior constrictor muscle originates from the lamina of the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid cartilage of the larynx. It inserts into the pharyngeal raphe and propels bolus downward.[2][10][11]

The cricopharyngeus muscle originates from the lowest portion of the inferior constrictor muscle and acts as a sphincter at the inferior terminus of the pharynx. It contributes to preventing the pharyngeal reflux of the contents of the esophagus.[2]

The stylopharyngeus muscle has its origin from the styloid process of the temporal bone and inserts into the posterior surface of the thyroid cartilage of the larynx. It helps elevate the pharynx during swallowing.[2]

The palatopharyngeus muscle originates from the palatine aponeurosis and inserts into the posterior surface of the thyroid cartilage. In addition to elevating the pharynx during swallowing, as it contracts, the palatopharyngeal arches are pulled medially. Also, it propels bolus during deglutition.[2][12]

The salpingopharyngeus muscle originates from the auditory tube and continues with the substance of the palatopharyngeus muscle. With the help of the previous two muscles, it elevates the pharynx when swallowing takes place.[2][13]

Physiologic Variants

As has been mentioned earlier, for the pharynx to fulfill its normal functions, it is to be positioned in the midline of the neck to convey air and food to the respiratory tract and digestive system, respectively. However, minor anatomical and physiological variants can be present mainly in regards to the musculature of the pharynx; these include additional attachments in terms of insertion of the longitudinal muscle group into the palatine tonsils and laryngeal cartilage including the epiglottis, arytenoid, and thyroid cartilage. Moreover, the salpingopharyngeus muscle is present in only 63% of cadavers, with the majority being thin individuals.[2]

Surgical Considerations

Performing surgical operations in the pharynx require delicate technique considering what this structure represents and also to the overlap of the neurovascular bundles and muscles overlying it.

A practitioner should be familiar with the structural components of the pharynx as the anatomical knowledge is fundamental in all traumatic and surgical cases, airway evaluation has to be considered, accordingly.[3][14][15][16][17]

Breathing issues, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), and malignancy resection all represent important surgical implications. Assessment of breathing and swallowing is considered crucial, especially in postoperative patients. Feeding tubes (an alternative way of food passage instead of passing through the mouth) are also of surgical importance. Also, preserving the stylopharyngeus muscle in lateral pharyngoplasty for the treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnea is indeed necessary.[2]

As part of airway management, the pharynx can be bypassed using endotracheal intubation. Furthermore, devices represent a means of control. If the ways mentioned above seem not possible, cricothyroidotomy can be a life-saving procedure. Airway obstruction due to tonsil enlargement and neck trauma outside the airway is of surgical importance especially when the latter causes elevated pressure leading to airway compromise which can be life-threatening and requires an immediate intervention such as thyroidectomy.[3]

Clinical Significance

Pharyngitis

The inflammation of the pharynx is also known as "sore throat." It can be brought about by several causative agents with the viruses being the commonest. Generally, the characteristic presentation is discomfort, pain, irritation, and dysphagia. The pain is treated using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for both adults and children. Aspirin is also also an option for adults. However, when the disease results from Streptococcus pyogenes, the etiologic diagnosis and specific treatment plan are needed.[18][19]

Dysphagia

As noted earlier, it is the inability to swallow properly due to muscle weakness, nerve damage, or certain diseases. It can lead to many complications, such as food or saliva aspiration, malnutrition, etc. Its prevalence is high in which approximately 50% of elderly patients and 50% of those with neurological dysfunctions have this condition.[2][20][21][22]

Adenoiditis

It is the inflammation of the adenoid lymph tissues that are present in the upper part of the nasal pharynx as has been explained earlier. It is present secondarily to an infection. Those usually affected present with cold-like symptoms, rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, and breathing problems.[22]

Sleep Apnea

The muscles of the pharynx can become hypotonic in certain occasions like during sleep. In such a case, they become too weak to prevent the collapse of the airways resulting in difficulty breathing. Several factors can be associated with sleep apnea, and those include obesity, generalized hypotonia, and large tongue (macroglossia).[2][23]

Zenker Diverticulum

In the laryngeal pharynx between the inferior constrictor and cricopharyngeus muscles is a small triangular gap called the Killian dehiscence. In the case of weakness or hypotonia, the pharyngeal mucosa and submucosa could get herniated and bulged between these two parts; this can lead to different problems as food accumulates in this herniation. Since such a diverticulum is confined to the mucosa and submucosa with no trace to the muscular layer, it is described as a false diverticulum.[24]

Other Issues

Cricopharyngeal Achalasia

A rare clinical condition in which the cricopharyngeus muscle does not open appropriately and adequately. Typically, during swallowing, the upper esophageal sphincter opens, allowing bolus to pass into the esophagus down the GIT. However, when the cricopharyngeus muscle is weak, food tends to leak, causing discomfort and dysphagia. In other words, failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax can lead to both difficulty swallowing and Zenker diverticulum.[2]