Introduction

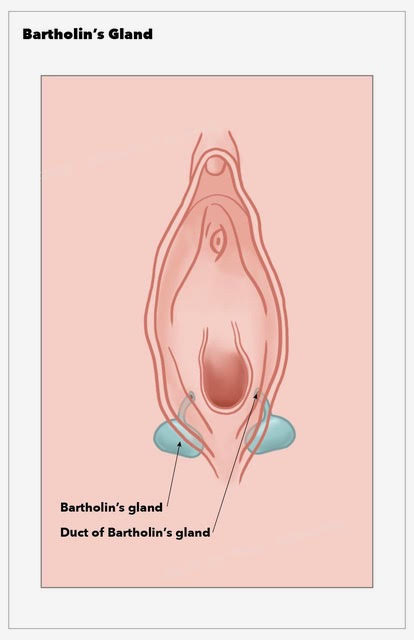

The Bartholin glands, also known as the greater vestibular glands, are important organs of the female reproductive system. Danish anatomist Caspar Bartholin Secundus first described these structures in 1677.[1] The glands primarily produce a mucoid secretion that aids vaginal and vulvar lubrication. The Bartholin glands are located in the vulvar vestibule on either side of the vaginal introitus (see Image. Bartholin Gland). These structures are homologous to the bulbourethral (Cowper) glands in men.

Bartholin gland pathology may present as an asymptomatic mass, causing only vulvar asymmetry. Symptomatic masses may exhibit severe tenderness, surrounding erythema, and edema. Cysts and abscesses often form in women of reproductive age and do not always require intervention. Mass biopsy and excision may be necessary if malignancy is suspected, though this occurrence is rare. In-depth knowledge of the anatomy and function of the Bartholin glands enables clinicians to treat various conditions affecting the female external genital area.

Structure and Function

The Bartholin glands are oval-shaped, measuring 0.5 cm on average. Each gland connects to the posterolateral aspect of the vaginal orifice, between the hymen and labia minora, through an efferent duct measuring 2 centimeters in length.

The primary function of the Bartholin glands is the production of a mucoid secretion that lubricates the distal vagina during intercourse. The glands become active after menarche and are normally impalpable.[2]

Embryology

During embryogenesis, the sinus urogenitalis gives rise to the Bartholin glands, the distal vagina, and the majority of its epithelium. The body of each Bartholin gland is composed of mucinous acini lined by simple columnar epithelium. The glands' efferent ducts are composed of transitional epithelium, which merges into squamous epithelium as the orifices open into the vagina.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The external pudendal artery supplies the Bartholin glands. Both glands drain into the superficial inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes.

Nerves

The pudendal nerve innervates the Bartholin glands, providing sensory and autonomic (parasympathetic) stimulation. Sensory innervation enables the perception of pain or discomfort, while autonomic stimulation supports the secretion of mucus for lubrication.

Surgical Considerations

Incision and Drainage with Word Catheter Placement

A scalpel is used to perform a medial incision into the cyst or abscess after the application of a local anesthetic. The incision should not be performed outside the labium majus to avoid fistula formation.[4] A Word catheter—a small, thin rubber tube with an inflatable balloon tip—is placed inside the cyst after evacuating its contents. The catheter may remain in place for up to 4 weeks for continuous drainage and reepithelization of the new outflow tract.

Marsupialization

A scalpel is used to perform an elliptical incision in the mucosa of the vulva and the underlying cyst wall. Care should be taken not to incise on the outer margin of the labium majus due to the risk of fistula formation. The edges of the cyst cavity are sewn to the surrounding tissue after draining the contents of the open cavity. This procedure forms a permanent open pocket, with the new outflow tract shrinking over time as it heals.

Surgical Excision

Excision of a Bartholin cyst or abscess may be required when office-based treatments fail. Possible complications include an increased risk of bleeding, postsurgical infection, pain secondary to scar tissue, and complications from general anesthesia. The surgical removal of Bartholin glands has not been shown to interfere with sexual function.[5] A specialist should perform this procedure.

The surgeon uses a scalpel to perform an elliptical incision in the vulvar mucosa. Care is necessary not to incise into the cyst or abscess. Dissection using sharp and blunt methods separates the lesion from the surrounding structures. The base of the Bartholin gland pathology is identified. The blood supply may be ligated using either cautery or suture. Then, the cyst or abscess may be removed entirely. The space where the Bartholin lesion used to be is closed with interrupted sutures utilizing a multilayer closure. The mucosal layer is closed with a simple running suture.

Other Treatment Methods

Carbon dioxide laser therapy can provide cyst vaporization in the outpatient setting. A study by Fambrini et al has concluded that CO2 laser vaporization is a safe and effective way to treat a Bartholin cyst, resulting in complete resolution.[6] Silver nitrate ablation following cyst drainage was as effective as marsupialization and caused less scar formation in a prospective randomized trial.[7] Procedures such as cyst or abscess fenestration and needle aspiration with or without alcohol sclerotherapy require further clinical research.

Clinical Significance

Bartholin gland cysts, abscesses, and masses may significantly affect a patient’s life. Pain and swelling can prevent sitting, walking, and intercourse. The diagnosis of Bartholin cysts and abscesses is often clinical. Atypical masses may require further imaging, tissue biopsy, or complete excision.

Bartholin Gland Cyst

Bartholin gland cysts account for approximately 2% of all gynecological visits every year.[8] A cyst may result from efferent duct obstruction, leading to mucous accumulation and gland distension. Cysts are frequently sterile and unilateral. These lesions present as painless masses, usually detected during a routine pelvic examination. Rarely, larger cysts may cause sexual discomfort or vulvar disfiguration.

Asymptomatic cysts in healthy patients may be treated conservatively.[9] A cyst that ruptures and drains spontaneously may only require sitz baths. In some cases, cysts may become enlarged, painful, or infected. Treatment options are available for symptom relief as well as cosmetic concerns. Antibiotics may be necessary in the case of secondary infection. Postmenopausal patients may need further investigations to rule out the possibility of cancer.

Bartholin Gland Abscess

Bartholin gland abscesses may result from either an infected cyst or a primary gland infection. These lesions typically present with severe pain and swelling, making sitting, walking, and sexual intercourse difficult. Other presenting signs and symptoms include acute, painful, unilateral vulvar swelling, erythema and edema surrounding a fluctuant vulvar mass, and sudden symptom relief following spontaneous mass discharge or rupture. Pyrexia is not a common feature in otherwise healthy patients.

Results from a study by Kessous et al describe the most common microbial pathogens associated with Bartholin abscesses. Escherichia coli was the most commonly found pathogen (43.6%), followed by Staphylococcus aureus (6.4%), group B Streptococci (4.8%), and Enterococcus spp (4.8%). Less than 10% of cases were polymicrobial in origin. E coli-positive cultures were more common in recurrent infections (56.8%) than in primary infections (37%).[10] Sexually transmitted infections were seldom causative, but testing for chlamydial and gonococcal infection remains important in susceptible patients. Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage is advisable in the absence of microbial sensitivities.

Numerous treatment options are available for symptomatic Bartholin cysts or abscesses. The most common interventions include incision and drainage with Word catheter placement and abscess marsupialization. A systematic review by Illingworth et al found that current randomized trial evidence does not support using any single surgical method.[11] The outcomes of other interventions, such as rubber ring catheter insertion, cavity closure, and alcohol sclerotherapy, have yet to be sufficiently studied. Bartholin cysts and abscesses rarely lead to complex and poorly understood complications, such as a rectovaginal fistula or a recto-Bartholin duct fistula.[12]

Bartholin Gland Benign Tumor

Benign solid lesions of the Bartholin gland rarely appear in the literature. Histopathology of excised glands includes nodular hyperplasia and adenoma.[13][14]

Bartholin Gland Carcinoma

Primary carcinoma of the Bartholin gland is rare, accounting for 1% to 5% of all vulvar malignancies.[15][16] The incidence of this condition is highest in women in the seventh decade. Atypical presentations of Bartholin gland pathology should raise suspicion for a possible carcinoma, especially in the presence of an enlarging asymptomatic vulvar mass in a postmenopausal woman. Malignant masses may also be fixed to the underlying tissues.

A retrospective cohort study concluded that Bartholin mass excision in postmenopausal women is not justified as a first-line treatment since the incidence of cancer is so low (0.114 per 100,000 woman-years). These patients may benefit from mass drainage and selective biopsy.[17] Adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma are the 2 most common histological types of primary Bartholin gland carcinoma. Other rarer types are transitional, adenoid-cystic, and undifferentiated carcinomas. Human papillomavirus type 16 has previously been detected via polymerase chain reaction in squamous cell carcinoma cases.[18]

Endometriosis of the Bartholin Gland

Rarely, primary endometriosis may affect the Bartholin gland. This condition may present with cyclic vulvar pain and swelling during menstruation in women of reproductive age. Wide excision of the affected gland or cyst is the mainstay of treatment.[19]

Other Issues

A retrospective cohort study found the incidence of Bartholin gland abscesses to be low (0.13%) during pregnancy. No significant difference was observed in pathogens found in culture-positive samples of pregnant and nonpregnant women.[20]