Introduction

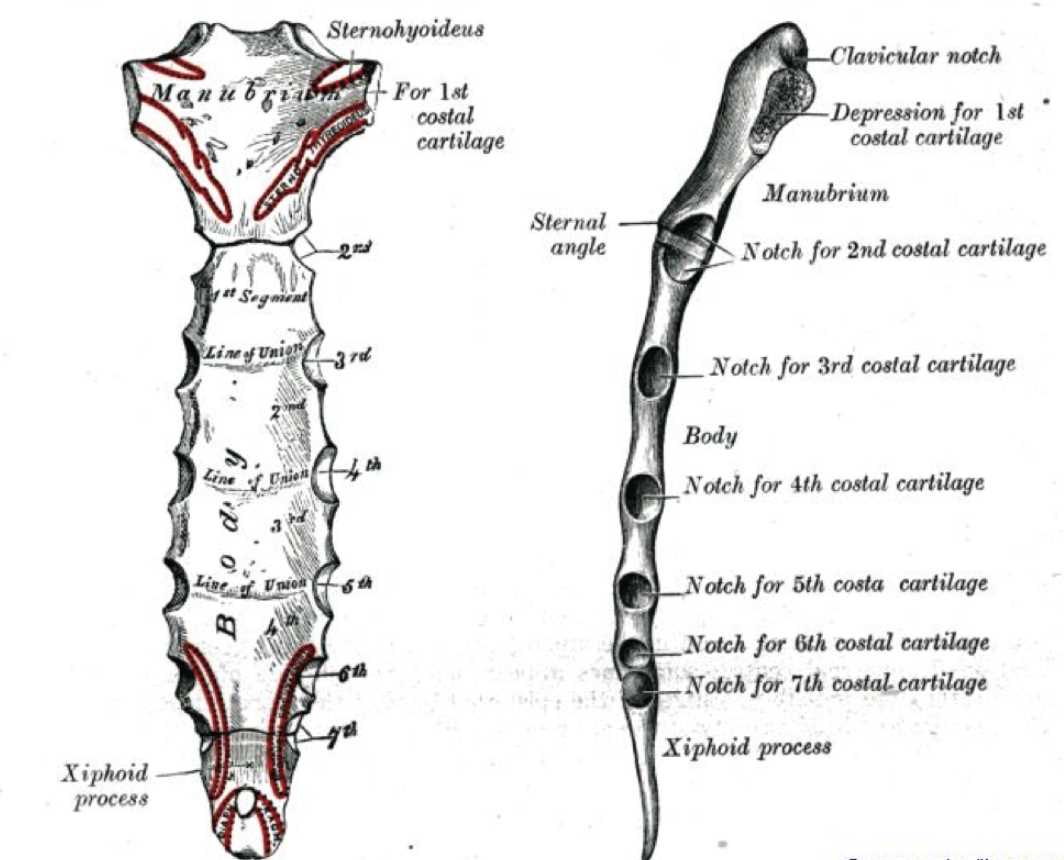

The angle of Louis is the eponymous name given to the sternal angle or the manubriosternal joint (see Image. Sternum). The angle of Louis is an important anatomical landmark, serving as a crucial reference point in clinical examinations and medical procedures. For example, clinicians use the sternal angle to guide stethoscope placement when auscultating heart and lung sounds. Radiologists also use this site as a reference point for assessing the positions of various thoracic structures in imaging studies.

The joint is slightly flexible in younger individuals due to inadequate development. Complete fusion of the angle of Louis generally occurs at approximately 30 years of age. Anomalies of the manubriosternal junction pose challenges in the clinical examination, radiological diagnosis, and therapy of thoracic conditions.

Structure and Function

Structure

The sternum consists of the manubrium, body, and xiphisternum. The manubrium is the widest and thickest of these segments, situated superiorly. The suprasternal (jugular) notch is at the manubrium's superior border, palpable between the clavicular heads. This nearly triangular bone measures 4 cm in length and lies at the level of the T3 and T4 bodies. The 1st rib's costal cartilage fuses with the lateral aspect of the manubrium inferolateral to the clavicular notch.

The sternal angle lies at the T4 to T5 intervertebral (IV) disk level. The manubrium and sternal body lie in different planes; hence, the angulation at the manubriosternal joint. The 2nd costal cartilage articulates with the lateral border of the joint. Thus, the angle of Louis is a convenient starting point for counting ribs anteriorly since the 1st rib is impalpable beneath the clavicle.[1] The manubriosternal junction or the angle of Louis is palpable as a transverse ridge in most individuals.

Clinicians recognize the manubriosternal joint as a synchondrosis, with soft hyaline cartilage connecting the 2 sternal segments. However, anatomists often classify this junction as a symphysis, joined by tough fibrocartilage and allowing only slight movements.[2]

Function

During inspiration, the vertical diameter of the central thoracic region increases as the diaphragm contracts and descends. During expiration, the lungs' elastic recoil reduces pleural cavity pressure and returns the thorax to its resting size.

Sternal movement during inspiration provides a "pump-handle" mechanism for anterosuperior thoracic expansion. The manubrium limits sternal mobility during this phase, but flexibility at the angle of Louis enables anterosuperior expansion of the chest and abdomen.[3][4]

Embryology

Sternum Development

The mesosternum begins to develop around the 6th gestational week, marked by the formation of craniocaudally oriented mesenchymal bars in the ventrolateral body wall of the developing embryo. From the 6th to 9th gestational weeks, the sternal primordia move medially, elongate, and interact with the growing primordial ribs, forming sternal bars. This process culminates in the midline fusion of these bars, starting from the manubrium and progressing craniocaudally.

By the 10th week, chondrification occurs, forming a single solid cartilaginous rod in the mid-anterior thorax. The caudal extension of these sternal bars beyond the last rib attachment gives rise to the xiphoid process.[5]

Manubrium Development

The development of the manubrium involves 3 distinct mesenchymal primordia: the presternal and paired suprasternal masses. During the 6th gestational week, the presternal mass emerges in the region mediocranial to the sternal bars and later merges with these bars. Simultaneously, the suprasternal masses form between the medial ends of the primordial clavicles and the presternum. The suprasternal masses later fuse with the presternum. This fusion creates the superior manubrial margin and the sternoclavicular joints.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Cadaveric studies reveal internal mammary artery branches perforating the sternum at each intercostal level. Associated veins have been identified following a similar course.[7][8] Importantly, in patients undergoing internal mammary harvesting, these perforating arteries anastomose with the intercostal arteries and indirectly with the posterior intercostal arteries. These connections enable collateral blood flow in the area. Despite this arrangement, studies have shown that a period of sternal ischemia ensues immediately after harvesting the internal mammary artery.[9]

Nerves

The intercostal nerves are somatic nerves supplying the sternum and manubrium. The main thoracic nerves supplying the sternum arise from the anterior rami of spinal nerve segments T2 to T6. These nerves stimulate intercostal muscle contraction and provide sensation to the skin. Unlike the lateral thorax, the manubrium and sternum have fewer nerves.

Muscles

The neck and thoracic muscles are directly attached to the manubrium and sternal body. The manubrium is an insertion point of the sternocleidomastoid, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid. The sternal body is an insertion point of the pectoralis major. Occasionally, the sternalis muscle lies superficial to the sternal body (see physiologic variants).

Three layers of intercostal muscles move the manubriosternal joint indirectly by their rib attachments. The external intercostals in the outermost layer have fibers running anteriorly and inferolaterally, elevating the ribs during inspiration. The internal intercostals lie deep to the external intercostals, oriented perpendicularly to the external intercostals. The innermost set of intercostals lies deep to the internal intercostals. These muscles are thin and oriented in the same direction as the internal intercostals.

Physiologic Variants

Sternal angle physiologic variants arise from differences in joint location, joint fusion, and joint angulation. An accessory muscle, the sternalis, is also found in some individuals. The clinical significance of these variations is explained below.

Joint Location

The manubriosternal joint is usually located at the insertion of the 2nd costal cartilage. However, the joint has been shown to extend to the 3rd costal cartilage insertion occasionally, which may affect physical examination and radiologic accuracy.[12]

Joint Fusion

Studies have shown that manubriosternal joint fusion can occur at any age. However, the 5-year age gap between nearly fused and fully fused joints implies a higher likelihood of fusion with advancing age. Notably, joint fusion was abnormal in 66% of cases, indicating that the joint's ability to pivot and increase the chest's front-to-back diameter might not significantly impact respiration in adult life.[10]

Joint Angulation

The reference interval for the sternal angle is 155-175 degrees. Exaggeration of this angle can be seen in some people and can affect thoracic movement.[11]

Sternalis Muscle

Some individuals may have a muscle lying superficially and parallel to the sternum known as the sternalis muscle. This muscle has no clear function but may be confused as a pathological structure or make sternal surgery challenging. The sternalis inserts proximally at the manubrium or superior aspect of the sternal body, but its distal insertion is variable.[12]

Healthcare providers must know these anatomical variants to prevent clinical examination and imaging errors.

Surgical Considerations

Surface Landmark For Thoracic Surgeries

Sternal angle surface landmarks are crucial to thoracic procedures. The 1st rib's impalpability makes the 2nd sternocostal joint at the angle of Louis a convenient starting point for rib counting.

The sternal angle is at the same level as the T4-to-T5 IV level, helping to locate deeper thoracic structures during surgery. The imaginary plane joining these 2 structures demarcates the inferior border of the superior mediastinum. The major structures in the superior mediastinum include the thymus, brachiocephalic veins, superior vena cava (SVC), aortic arch, vagus and phrenic nerves, trachea, and esophagus.

The trachea forms the carina at the level of the sternal angle, bifurcating into the right and left main bronchi. The angle of Louis also marks the level of the ligamentum arteriosum and the point where the left recurrent laryngeal nerve loops below the aortic arch. At this level, the azygos vein also arches anteriorly over the right hilum to enter the SVC, while the thoracic duct crosses over to the left side of the chest from the abdomen.

Sternocostal articulations vary in length in the first 7 ribs. The inferior 5 ribs do not articulate with the sternum. The costochondral junctions align from a point 5 cm from the midline at the sternal angle to 2.5 cm posteroinferior to the 10th costal cartilage.

Sternotomy

Sternotomy is widely regarded as the optimal incision technique in cardiac surgery, with low failure rates and consistently favorable long-term outcomes. Sternotomy's applicability extends to thoracic surgery for procedures involving the mediastinum and pulmonary regions. Proper execution of this procedure minimizes short- and long-term morbidity and mortality after thoracic surgery.

Key steps in the procedure include accurate landmark identification, meticulous midline tissue preparation, careful osteotomy, and targeted bleeding control.[14]

Clinical Significance

Chest Physical Examination

Palpating the sternal angle helps locate the 2nd rib and intercostal spaces when auscultating the chest. Typically, the optimal site for listening to the aortic valve is the right 2nd intercostal space. For the pulmonic valve, it is usually the left 2nd intercostal space. The tricuspid valve is commonly heard between the 4th and 5th intercostal spaces, while mitral valve sounds are best heard in the 5th intercostal space. Accurately locating the intercostal spaces likewise helps diagnose respiratory diseases.[15]

Sternal Variations and Thoracic Injury Tolerance

Age- and sex-related sternal changes have been found to correlate with the risk of thoracic injury. Sternal and manubrial shape, size, and ossification vary with age. The sternum and manubrium are narrower and less ossified in children than adults. Thus, thoracic organ injuries are more prevalent in children than thoracic fractures. Ossification without substantial sternal size and shape changes increases the risk of sternal fractures in adults.[13]

Other Issues

The eponymous name "angle of Louis” is believed to have originated from either Antoine Louis, a French clinician, or Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, a German physician. However, there is no definitive evidence of either origin, and some even speculate that the name originates from another doctor, Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis.